Reconceptualizing the Alien: Jews in Modern Ukrainian Thought*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ukrainian Weekly 1989, No.11

www.ukrweekly.com ЇЇ5ІГв(І by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.. a fraternal non-profit association| ШrainianWeekl Y Vol. LVII No. 11 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MARCH 12, 1989 50 cents Accused by Russian Orthodox Church Ukrainian H/lemorial Society confronts Iryna Kalynets, Mykhailo Horyn vestiges of Stalinism in Ulcraine to be tried for 'inciting' faithful by Bohdan Nahaylo which suffered so much at the hands of JERSEY CITY, N.J. - Ukrainian The charges, which stem from the the Stalinist regime, there has been a Another important informal associa national and religious rights activists dissidents' participation in a moleben in strong response to the new anti-Stalin tion has gotten off to an impressive Iryna Kalynets and Mykhailo Horyn front of St. George's Cathedral in Lviv, campaign that has developed since start in Ukraine, strengthening the have been accused by the Russian commemorating Ukrainian Indepen Mikhail Gorbachev ushered in glasnost forces pushing for genuine democrati and democratization. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Lviv eparchy, of dence Day on January 22, claim that zation and national renewal in the cultural intelligentsia, especially the instigating religious conflicts among Mrs. Kalynets and Mr. Horyn yelled republic. On March 4, the Ukrainian writers, as well as a host of new informal believers. Their trial was scheduled tor obscenities directed at Metropolitan Memorial Society held its inaugural groups, have sought a more honest March 9 and 10. Nikodium, hierarch of the Russian Or conference in Kiev. The following day, depiction of Ukraine's recent past and thodox Church in Lviv. several thousand people are reported to the rehabilitation of the victims of Investigators have questioned a num have taken part in the society's first' political terror. -

Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics: Implications For

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTIO N AUTHORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky Tönu Parming CONTRACTOR : University of Delawar e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky, Project Director an d Co-Principal Investigato r Tönu Parming, Co-Principal Investigato r COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 621- 9 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part fro m funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . NOTICE OF INTENTION TO APPLY FOR COPYRIGH T This work has been requested for manuscrip t review for publication . It is not to be quote d without express written permission by the authors , who hereby reserve all the rights herein . Th e contractual exception to this is as follows : The [US] Government will have th e right to publish or release Fina l Reports, but only in same forma t in which such Final Reports ar e delivered to it by the Council . Th e Government will not have the righ t to authorize others to publish suc h Final Reports without the consent o f the authors, and the individua l researchers will have the right t o apply for and obtain copyright o n any work products which may b e derived from work funded by th e Council under this Contract . ii EXEC 1 Overall Executive Summary HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTION by Yaroslav Bilinsky, University of Delawar e d Tönu Parming, University of Marylan August 1, 1975, after more than two years of intensive negotiations, 35 Head s of Governments--President Ford of the United States, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada , Secretary-General Brezhnev of the USSR, and the Chief Executives of 32 othe r European States--signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperatio n in Europe (CSCE) . -

The Making of the Poetic Subject in Vasyl Stus's

‘A FRAGMENT OF WHOLENESS’: THE MAKING OF THE POETIC SUBJECT IN VASYL STUS’S PALIMPSESTS Bohdan Tokarskyi St John’s College University of Cambridge The dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2019 PREFACE This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of 80,000 words. ii ABSTRACT Bohdan Tokarskyi ‘A Fragment of Wholeness’: The Making of the Poetic Subject in Vasyl Stus’s Palimpsests My PhD thesis investigates the exploration of the self and the innovative poetical language in the works of the Ukrainian dissident poet and Gulag prisoner Vasyl Stus (1938-1985). Focusing on Stus’s magnum opus collection Palimpsests (1971-1979), where the poet casts the inhuman conditions of his incarceration to the periphery and instead engages in radical introspection, I show how Stus’s poetry foregrounds the very making of the subject as the constant pursuit of the authentic self. Through my examination of unpublished archival materials, analysis of Stus’s underexplored poems, and the contextualisation of the poet’s works within the tradition of the philosophy of becoming, I propose a new reading of Palimpsests, one that redirects scholarly attention from the historical and political to the psychological and philosophical. -

"Prisoners of the Caucasus: Literary Myths and Media Representations of the Chechen Conflict" by H

University of California, Berkeley Prisoners of the Caucasus: Literary Myths and Media Representations of the Chechen Conflict Harsha Ram Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Working Paper Series This PDF document preserves the page numbering of the printed version for accuracy of citation. When viewed with Acrobat Reader, the printed page numbers will not correspond with the electronic numbering. The Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies (BPS) is a leading center for graduate training on the Soviet Union and its successor states in the United States. Founded in 1983 as part of a nationwide effort to reinvigorate the field, BPSs mission has been to train a new cohort of scholars and professionals in both cross-disciplinary social science methodology and theory as well as the history, languages, and cultures of the former Soviet Union; to carry out an innovative program of scholarly research and publication on the Soviet Union and its successor states; and to undertake an active public outreach program for the local community, other national and international academic centers, and the U.S. and other governments. Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies University of California, Berkeley Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies 260 Stephens Hall #2304 Berkeley, California 94720-2304 Tel: (510) 643-6737 [email protected] http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~bsp/ Prisoners of the Caucasus: Literary Myths and Media Representations of the Chechen Conflict Harsha Ram Summer 1999 Harsha Ram is an assistant professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at UC Berkeley Edited by Anna Wertz BPS gratefully acknowledges support from the National Security Education Program for providing funding for the publication of this Working Paper . -

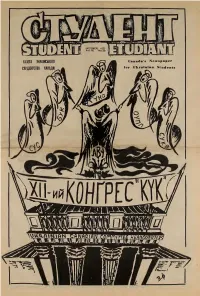

STUDENT 1977 October

2 «««««••••••«•»» : THE PRESIDENT : ON SUSK Andriy Makuch : change in attitude is necessary. • • The book of Samuel relates how This idea was reiterated uyzbyf the young David stood before • Marijka Hurko in opening the I8th S • Goliath and proclaimed his In- Congress this year, and for- tention slay him. The giant was 2 3 to malized by Andrij Semotiuk's.© • amazed and took tight the threat; presentation of "The Ukrainian • subsequently, he was struck down • Students' Movement In Context" J • by a well-thrown rock. Since then, (to be printed in the next issue of • giants have taken greater heed of 2 STUDENT). It was a most listless such warnings. 2 STUDENT • Congress - the • seek and disturbing " I am not advocating we 11246-91 St. ritual burying of an albatross wish to J Edmonton. Alberta 2 Goliaths to slay, but rather mythology. There were no great • underline that a well-directed for- Canada TSB 4A2 funeral orations, no tears cried. ce can be very effective • par- • No one cared. Not that they were f ticularly if it is judiciously applied. the - incapable of it, but because , SUSK must keep this in mind over , £ entire issue was so far removed 5 9• the coming yeayear. The problems ' trom their own reality (especially ft . t we, as part off thett Ukrainian corn- - those attending their first " £ . community, no face are for- - Congress), that they had no idea • midable, andi theretht is neither time of why they should. Such a sad and bi-monthly news- nor manpower to waste. "STUDENT" is a national tri- ft spectacle must never be repeated by • The immediate necessity is to students and is published - entrenched Ideas can be very • paper for Ukrainian Canadian realistically assess our priorities 2 limiting. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1990

Published by the Ukrainian National Association inc.. a fraternal non-profit association rainian Weekly vol. LVIII No. 47 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 25,1990 50 cents Ukraine, Baltic states and Armenia Patriarch Mstyslav enthroned send representatives to Paris summit Historic services held at St Sophia Cathedral JERSEY C1TY, N.J. - Representa– of an urgent meeting, and later would SOUTH BOUND BROOK, N.J. - witness the service from the knaveof the tives of Ukraine, the Baltic states and not let them re-enter the hall. French His Holiness Mstyslav was enthroned church, which was filled with believers. Armenia sent their own representatives Foreign Minister Roland Dumas told as patriarch of Kiev and all Ukraine on Among the dignitaries attending the to the Paris summit of the Conference the Baits they were being expelled Sunday, November 18,in Kiev, reported ceremony were chairman of the Council on Security and Cooperation in "because the Soviet delegation was the metropolitan's chancery of the for Religious Affairs of the Ukrainian Europe meeting in Paris on November totally against their participation in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the SSR, Mykola Kolesnyk, deputies to the 19-21. conference," reported RFE^RL. U.S.A. based here. Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, The representatives traveled to the As planned, the solemnities were held Mykhailo Horyn, Serhiy Holovaty, meeting as unofficial delegations and The Ukrainian delegation consisted of in St. Sophia Cathedral, which local Mykola Porovsky and vasyl Cher– observers. three people's deputies: Dmytro Pavly– authorities handed over to the believers voniy, deputy to the Supreme Soviet of However, Baltic representatives, who chko, chairman, Bohdan Horyn, co- of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Ortho– the USSR, Yuri Sorochyk, as well as had arrived in Paris as observers on chairman, and ivan Drach, a member, dox Church for that day. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1975, No.43

www.ukrweekly.com РІК LXXXH. SECTION TWO No. 210 SVOBODA, THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY, SATURDAY. NOVEMBER 8,1975 ЦЕНТІВ 20 CENTS 4. 210 VOL. Lxxxn. FRENCH G0MMUN1ST PARTY J2URNAL DEMANDS APPEAL SEN. JACKSON UNDERSCORES PL1GHT OF UKRA1N1AN OF THE UKRAINIAN CONGRESS COMMITTEE RELEASE OF LEONiD PL1USHGH OF AMERICA FOR CONTRIBUTIONS PR1S0NERS1N LETTERS TO FORD, BREZHNEY TO THE UKRAINIAN NATIONAL FUND PAR1S. France. - "L'Hu– complete disagreement, and ry of the French Socialist WASHINGTON, D.C - "lt Ь?дізо especially dis– manite," the official organ of demand that he be released Party, said that he was ap– FR1ENDS: Sen. Нешу Jackson (D.– ШгЬ:рз to me that many the French Communist Par– as soon as possible," wrote proached by many people Wash.) underscored the у -r^; women have been im– ty. in its Saturday, October Andre. voicing apprehension over the We appeal to you, as we have in previous years, to con- plight of Ukrainian political j prisoped in recent years sim– 25th edition, editorially de– Some thirty representati– rally. He said they considered tribute your annual donation the Ukrainian National Fund. prisoners in separate letters j ply for endeavoring to exer– manded that the Soviet go– ves of French labor - unions, that to much concern was be– We appeal to you, our conscientious and generous ci– to President Gerald Ford and j cise their cultural freedom as vernment immediately release po!ifical life, and academic ing expressed on behalf of one tizens, who, through their annual contributions, have sustain– Soviet Communist Party chief Ukrainians — among them Leonid Pliushch from psy– and professional sph?res is– person. -

The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943 Author(S): Timothy Snyder Source: Past & Present, No

The Past and Present Society The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943 Author(s): Timothy Snyder Source: Past & Present, No. 179 (May, 2003), pp. 197-234 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600827 . Accessed: 05/01/2014 17:29 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Past &Present. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.110.33.183 on Sun, 5 Jan 2014 17:29:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE CAUSES OF UKRAINIAN-POLISH ETHNIC CLEANSING 1943* Ethniccleansing hides in the shadow of the Holocaust. Even as horrorof Hitler'sFinal Solution motivates the study of other massatrocities, the totality of its exterminatory intention limits thevalue of the comparisons it elicits.Other policies of mass nationalviolence - the Turkish'massacre' of Armenians beginningin 1915, the Greco-Turkish'exchanges' of 1923, Stalin'sdeportation of nine Soviet nations beginning in 1935, Hitler'sexpulsion of Poles and Jewsfrom his enlargedReich after1939, and the forcedflight of Germans fromeastern Europein 1945 - havebeen retrievedfrom the margins of mili- tary and diplomatichistory. -

Zhuk Outcover.Indd

The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Sergei I. Zhuk Number 1906 Popular Culture, Identity, and Soviet Youth in Dniepropetrovsk, 1959–84 The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Number 1906 Sergei I. Zhuk Popular Culture, Identity, and Soviet Youth in Dniepropetrovsk, 1959–84 Sergei I. Zhuk is Associate Professor of Russian and East European History at Ball State University. His paper is part of a new research project, “The West in the ‘Closed City’: Cultural Consumption, Identities, and Ideology of Late Socialism in Soviet Ukraine, 1964–84.” Formerly a Professor of American History at Dniepropetrovsk University in Ukraine, he completed his doctorate degree in Russian History at the Johns Hopkins University in 2002 and recently published Russia’s Lost Reformation: Peasants, Millennialism, and Radical Sects in Southern Russia and Ukraine, 1830–1917 (2004). No. 1906, June 2008 © 2008 by The Center for Russian and East European Studies, a program of the University Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh ISSN 0889-275X Image from cover: Rock performance by Dniepriane near the main building of Dniepropetrovsk University, August 31, 1980. Photograph taken by author. The Carl Beck Papers Editors: William Chase, Bob Donnorummo, Ronald H. Linden Managing Editor: Eileen O’Malley Editorial Assistant: Vera Dorosh Sebulsky Submissions to The Carl Beck Papers are welcome. Manuscripts must be in English, double-spaced throughout, and between 40 and 90 pages in length. Acceptance is based on anonymous review. Mail submissions to: Editor, The Carl Beck Papers, Center for Russian and East European Studies, 4400 Wesley W. Posvar Hall, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1990

ublished by the Ukrainian National Association inc.. a fraternal non-profit association rainian Weekly vol. LVIII No. 51 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, DECEMBER 23,1990 50 cents U.S., USSR sign Faithful in U.S. celebrate Patriarch Mstyslav's return agreement on by Marta Kolomayets SOUTH BOUND BROOK, N.J. - consulates "A new joy has emerged" ("Nova radist stala"), proclaimed Patriarch Mstyslav WASHINGTON - The united І of Kiev and all Ukraine during his first States and the Soviet Union have an– patriarchal liturgy at St. Andrew's nounced an agreement to open a U.S. Memorial Church since his enthrone– consulate general in Kiev and a Soviet ment as prelate of the Ukrainian consulate general in New York, culmi– Autocephalous Orthodox Church in nating years of contacts about the issue. Kiev on Sunday, November 18. The two sides reached agreement Addressing hundreds of faithful who December 10, when Secretary of State filled this seat of Ukrainian Orthodoxy James Baker and Soviet Foreign Mi– on Sunday, December 16, Patriarch nister Eduard Shevardnadze met Mstyslav described his moving six– week in Houston. State Department pilgrimage to Ukraine, a triumphant Spokesman Margaret Tutwiler issued a return to his native land after an written joint statement on December 13 absence of 46 years. announcing the decision. There, thousands of believers, de– Consuls general and staff have al– nied freedom of worship for decades, ready been appointed, but they were not had greeted the 92-year-old primate named in the announcement. Both with the traditional welcome of bread missions are to begin operations in and salt. -

A Microhistory of Ukraine's Generation of Cultural Rebels

This article was downloaded by: [Selcuk Universitesi] On: 07 February 2015, At: 17:31 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cnap20 The early 1960s as a cultural space: a microhistory of Ukraine's generation of cultural rebels Serhy Yekelchyka a Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies, University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada Published online: 10 Oct 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Serhy Yekelchyk (2015) The early 1960s as a cultural space: a microhistory of Ukraine's generation of cultural rebels, Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity, 43:1, 45-62, DOI: 10.1080/00905992.2014.954103 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2014.954103 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Anti-Imperial Choice This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Anti-Imperial Choice the Making of the Ukrainian Jew

the anti-imperial choice This page intentionally left blank The Anti-Imperial Choice The Making of the Ukrainian Jew Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern Yale University Press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Ehrhardt type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petrovskii-Shtern, Iokhanan. The anti-imperial choice : the making of the Ukrainian Jew / Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-13731-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Jewish literature—Ukraine— History and criticism. 2. Jews in literature. 3. Ukraine—In literature. 4. Jewish authors—Ukraine. 5. Jews— Ukraine—History— 19th century. 6. Ukraine—Ethnic relations. I. Title. PG2988.J4P48 2009 947.7Ј004924—dc22 2008035520 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). It contains 30 percent postconsumer waste (PCW) and is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). 10987654321 To my wife, Oxana Hanna Petrovsky This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Politics of Names and Places: A Note on Transliteration xiii List of Abbreviations xv Introduction 1 chapter 1.