The Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Citizens' Peace Movement in the Soviet Baltic Republics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2kk0x6vm Journal Journal of Peace Research, 23(2) ISSN 0022-3433 Author Taagepera, R Publication Date 1986 DOI 10.1177/002234338602300208 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Citizens’ Peace Movement in the Soviet Baltic Republics* REIN TAAGEPERA School of Social Sciences, University of California A citizens’ peace movement emerged in the Soviet Baltic republics in January 1980, when about 23 Lithuanians, Estonians, and Latvians signed an antiwar declaration in the wake of Soviet military in- volvement in Afghanistan. The concern for peace was intertwined with, but distinct from, concerns for national autonomy, civil rights, and ecology. The movement culminated with a proposal in October 1981 that the Baltic republics be enclosed in the Nordic Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone. This proposal was signed by 38 Latvians, Lithuanians, and Estonians, in response to Brezhnev’s offer to consider some NWFZ-related measures ’applicable to our own territory’. At least five of the signatories have been jailed since then, and at least in one case the NWFZ proposal figured among the most incriminating char- ges. Despite some remaining problems of wording, the Baltic Letter on the NWFZ represented a major advance from uncompromising declaratory dissent toward advocacy of specific and negotiable mea- sures. The Baltic action preceded and partly inspired the formation of the now-defunct citizens’ peace group in Moscow, 1982. The demand for inclusion of the Baltic republics in the Nordic NWFZ was re- peated in a December 1983 letter by unnamed Estonian Peace Supporters to the Stockholm disarmament conference, in a rather declaratory style. -

Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics: Implications For

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTIO N AUTHORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky Tönu Parming CONTRACTOR : University of Delawar e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky, Project Director an d Co-Principal Investigato r Tönu Parming, Co-Principal Investigato r COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 621- 9 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part fro m funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . NOTICE OF INTENTION TO APPLY FOR COPYRIGH T This work has been requested for manuscrip t review for publication . It is not to be quote d without express written permission by the authors , who hereby reserve all the rights herein . Th e contractual exception to this is as follows : The [US] Government will have th e right to publish or release Fina l Reports, but only in same forma t in which such Final Reports ar e delivered to it by the Council . Th e Government will not have the righ t to authorize others to publish suc h Final Reports without the consent o f the authors, and the individua l researchers will have the right t o apply for and obtain copyright o n any work products which may b e derived from work funded by th e Council under this Contract . ii EXEC 1 Overall Executive Summary HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTION by Yaroslav Bilinsky, University of Delawar e d Tönu Parming, University of Marylan August 1, 1975, after more than two years of intensive negotiations, 35 Head s of Governments--President Ford of the United States, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada , Secretary-General Brezhnev of the USSR, and the Chief Executives of 32 othe r European States--signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperatio n in Europe (CSCE) . -

Dissidents Versus Communists

DISSIDENTS VERSUS COMMUNISTS An Examination of the Soviet Dissidence Movement Matthew Williams Professor Transchel History 419 May 12, 2016 Williams 1 On February 25, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev gave a speech to the Twentieth Congress and to the Communist Party stating that Joseph Stalin was responsible for all of the empire’s then-current issues. He also gave insight into the criminal actions performed by the man during his lifetime. This speech was called the “Secret Speech” as it was not publicized at first, but once word got out about the true nature of Stalin, people began to doubt everything they knew to be true. Khrushchev decreased the censorship and restrictions on people and also freed millions of political prisoners from Gulags, beginning what would come to be referred to as the “thaw”. Many people had practically worshipped Stalin and knew him to represent the Communist party’s creed of infallibility. The tarnishing of his image led many people to seriously doubt the capabilities of the party.1 As truths came out and people began to discuss issues, there was increasing dissatisfaction with the Communist Party and a community of dissenters was born. This community of dissenters would ultimately keep the fight for freedom going long after the end of the thaw era, until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. This paper will examine the dissent movement, from its roots in the end of the Stalin era to the collapse in 1991; it will address how the dissent movement came into being, and how it evolved as new challenges were presented to it. -

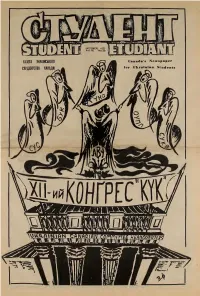

STUDENT 1977 October

2 «««««••••••«•»» : THE PRESIDENT : ON SUSK Andriy Makuch : change in attitude is necessary. • • The book of Samuel relates how This idea was reiterated uyzbyf the young David stood before • Marijka Hurko in opening the I8th S • Goliath and proclaimed his In- Congress this year, and for- tention slay him. The giant was 2 3 to malized by Andrij Semotiuk's.© • amazed and took tight the threat; presentation of "The Ukrainian • subsequently, he was struck down • Students' Movement In Context" J • by a well-thrown rock. Since then, (to be printed in the next issue of • giants have taken greater heed of 2 STUDENT). It was a most listless such warnings. 2 STUDENT • Congress - the • seek and disturbing " I am not advocating we 11246-91 St. ritual burying of an albatross wish to J Edmonton. Alberta 2 Goliaths to slay, but rather mythology. There were no great • underline that a well-directed for- Canada TSB 4A2 funeral orations, no tears cried. ce can be very effective • par- • No one cared. Not that they were f ticularly if it is judiciously applied. the - incapable of it, but because , SUSK must keep this in mind over , £ entire issue was so far removed 5 9• the coming yeayear. The problems ' trom their own reality (especially ft . t we, as part off thett Ukrainian corn- - those attending their first " £ . community, no face are for- - Congress), that they had no idea • midable, andi theretht is neither time of why they should. Such a sad and bi-monthly news- nor manpower to waste. "STUDENT" is a national tri- ft spectacle must never be repeated by • The immediate necessity is to students and is published - entrenched Ideas can be very • paper for Ukrainian Canadian realistically assess our priorities 2 limiting. -

Conde, Jonathan (2018) an Examination of Lithuania's Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation

Conde, Jonathan (2018) An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Masters thesis, York St John University. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/3522/ Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Research MA History at York St John University School of Humanities, Religion & Philosophy by Jonathan William Conde Student Number: 090002177 April 2018 I confirm that the work submitted is my own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the works of others. This copy has been submitted on the understanding that it is copyright material. Any reuse must comply with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and any licence under which this copy is released. @2018 York St John University and Jonathan William Conde The right of Jonathan William Conde to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Acknowledgments My gratitude for assisting with this project must go to my wife, her parents, wider family, and friends in Lithuania, and all the people of interest who I interviewed between the autumn of 2014 and winter 2017. -

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

Prenesi Datoteko Prenesi

From War to Peace: The Literary Life of Georgia after the Second World War Irma Ratiani Ivane Javakhishvili, Tbilisi State University, Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature, 1 Chavchavadze Ave, Tbilisi 0179, Georgia [email protected] After the Second World War, political changes occurred in the Soviet Union. In 1953 Joseph Stalin—originally Georgian and the incarnate symbol of the country— died, and soon the much-talked-about Twentieth Assembly of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union headed by Nikita Khrushchev followed in 1956. In Georgia, Khrushchev’s speech against Stalin was followed by serious political unrest that ended with the tragic events of March 9th, 1956. It is still unclear whether this was a political event or demonstration of insulted national pride. Soon after that, the Khrushchev Thaw (Russian: Ottepel) occurred throughout the Soviet Union. The literary process during the Thaw yielded quite a different picture compared to the previous decades of Soviet life. Under the conditions of political liberalization, various tendencies were noticed in Georgian literary space: on the one hand, there was an obvious nostalgia for Stalin, and on the other hand there was the growth of a specific model of Neo-Realism and, of no less importance, the rise of women’s writing. Keywords: literature and ideology / Georgian literature / World War II / Khrushchev thaw / Soviet Union Modifications of the Soviet regime Georgian literature before the Second World War was by no means flourishing. As a result of the political purges of the 1930s conducted by Soviet government, the leading Georgian writers were elimi- nated. -

Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past: a Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region

CBEES State of the Region Report 2020 Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region Published with support from the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjstiftelsen) Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region December 2020 Publisher Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, CBEES, Sdertrn University © CBEES, Sdertrn University and the authors Editor Ninna Mrner Editorial Board Joakim Ekman, Florence Frhlig, David Gaunt, Tora Lane, Per Anders Rudling, Irina Sandomirskaja Layout Lena Fredriksson, Serpentin Media Proofreading Bridget Schaefer, Semantix Print Elanders Sverige AB ISBN 978-91-85139-12-5 4 Contents 7 Preface. A New Annual CBEES Publication, Ulla Manns and Joakim Ekman 9 Introduction. Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past, David Gaunt and Tora Lane 15 Background. Eastern and Central Europe as a Region of Memory. Some Common Traits, Barbara Trnquist-Plewa ESSAYS 23 Victimhood and Building Identities on Past Suffering, Florence Frhlig 29 Image, Afterimage, Counter-Image: Communist Visuality without Communism, Irina Sandomirskaja 37 The Toxic Memory Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, Thomas de Waal 45 The Flag Revolution. Understanding the Political Symbols of Belarus, Andrej Kotljarchuk 55 Institutes of Trauma Re-production in a Borderland: Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania, Per Anders Rudling COUNTRY BY COUNTRY 69 Germany. The Multi-Level Governance of Memory as a Policy Field, Jenny Wstenberg 80 Lithuania. Fractured and Contested Memory Regimes, Violeta Davoliūtė 87 Belarus. The Politics of Memory in Belarus: Narratives and Institutions, Aliaksei Lastouski 94 Ukraine. Memory Nodes Loaded with Potential to Mobilize People, Yuliya Yurchuk 106 Czech Republic. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-Wednesday, January 22, 1986 the House Met at 3 P.M

January 22, 1986 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 219 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-Wednesday, January 22, 1986 The House met at 3 p.m. can be lowered further and the value As a result, Federal workers are in The Chaplain, Rev. James David of the dollar can decline to the point creasingly unwilling to report wrong Ford, D.D., offered the following where U.S. commodity exports regain doing. They are fearful that they will prayer: a measure of competitiveness. But be subject to reprisal, and all too often Grant to all who labor in this place, time is a commodity that many farm they are right. A Merit System Protec 0 God, the fullness of Your grace. ers have run out of. Only through full tion Board study in 1983 found a Give to each person wisdom needed implementation of the income protec sharp increase from 1980 in the for judgment, courage needed for tion provisions of the 1985 farm bill number of Federal employees who said action, understanding needed for can we provide our farmers with the that reporting official wrongdoing unity, and the dedication and commit time they need to recover. posed too great a personal risk. ment needed for justice. Bless us this Today, I, along with a bipartisan day and every day. Amen. WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION group of Senators and Representa ACT OF 1986 tives, am introducing the Whistleblow THE JOURNAL er Protection Act of 1986. This legisla <Mrs. SCHROEDER asked and was tion reaffirms congressional support The SPEAKER. The Chair has ex given permission to address the House for whistleblowers and provides in amined the Journal of the last day's for 1 minute and to revise and extend her remarks.) creased protection for the rights of proceedings and announces to the Federal employees who disclose Gov House his approval thereof. -

Human Rights and History a Challenge for Education

edited by Rainer Huhle HUMAN RIGHTS AND HISTORY A CHALLENGE FOR EDUCATION edited by Rainer Huhle H UMAN The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Genocide Convention of 1948 were promulgated as an unequivocal R response to the crimes committed under National Socialism. Human rights thus served as a universal response to concrete IGHTS historical experiences of injustice, which remains valid to the present day. As such, the Universal Declaration and the Genocide Convention serve as a key link between human rights education and historical learning. AND This volume elucidates the debates surrounding the historical development of human rights after 1945. The authors exam- H ine a number of specific human rights, including the prohibition of discrimination, freedom of opinion, the right to asylum ISTORY and the prohibition of slavery and forced labor, to consider how different historical experiences and legal traditions shaped their formulation. Through the examples of Latin America and the former Soviet Union, they explore the connections · A CHALLENGE FOR EDUCATION between human rights movements and human rights education. Finally, they address current challenges in human rights education to elucidate the role of historical experience in education. ISBN-13: 978-3-9810631-9-6 © Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” Stiftung “Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft” Lindenstraße 20–25 10969 Berlin Germany Tel +49 (0) 30 25 92 97- 0 Fax +49 (0) 30 25 92 -11 [email protected] www.stiftung-evz.de Editor: Rainer Huhle Translation and Revision: Patricia Szobar Coordination: Christa Meyer Proofreading: Julia Brooks and Steffi Arendsee Typesetting and Design: dakato…design. David Sernau Printing: FATA Morgana Verlag ISBN-13: 978-3-9810631-9-6 Berlin, February 2010 Photo Credits: Cover page, left: Stèphane Hessel at the conference “Rights, that make us Human Beings” in Nuremberg, November 2008. -

Russia 2012-2013: Attack on Freedom / 3 Introduction

RUSSIA 2012-2013 : Attack on Freedom Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, February 2014 / N°625a Cover photo: Demonstration in front of the State Duma (Russian Parliament) in Moscow on 18 July 2013, after the conviction of Alexei Navalny. © AFP PHOTO / Ivan Novikov 2 / Titre du rapport – FIDH Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 1. Authoritarian Methods to Suppress Rights and Freedoms -------------------------------- 6 2. Repressive Laws ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 2.1. Restrictions on Freedom -

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN the LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist Degree, Belarusian State University

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist degree, Belarusian State University, 2001 Master of Arts, Brock University, 2005 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Olga Klimova It was defended on May 06, 2013 and approved by David J. Birnbaum, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Lucy Fischer, Distinguished Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Aleksandr Prokhorov, Associate Professor, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, College of William and Mary, Virginia Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Condee, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Olga Klimova 2013 iii SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES Olga Klimova, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The central argument of my dissertation emerges from the idea that genre cinema, exemplified by youth films, became a safe outlet for Soviet filmmakers’ creative energy during the period of so-called “developed socialism.” A growing interest in youth culture and cinema at the time was ignited by a need to express dissatisfaction with the political and social order in the country under the condition of intensified censorship. I analyze different visual and narrative strategies developed by the directors of youth cinema during the Brezhnev period as mechanisms for circumventing ideological control over cultural production.