To What Extent Was Makhno Able to Implement Anarchist Ideals During the Russian Civil War?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rancour's Emphasis on the Obviously Dark Corners of Stalin's Mind

Rancour's emphasis on the obviously dark corners of Stalin's mind pre- cludes introduction of some other points to consider: that the vozlzd' was a skilled negotiator during the war, better informed than the keenly intelli- gent Churchill or Roosevelt; that he did sometimes tolerate contradiction and even direct criticism, as shown by Milovan Djilas and David Joravsky, for instance; and that he frequently took a moderate position in debates about key issues in the thirties. Rancour's account stops, save for a few ref- erences to the doctors' plot of 1953, at the end of the war, so that the enticing explanations offered by William McCagg and Werner Hahn of Stalin's conduct in the years remaining to him are not discussed. A more subtle problem is that the great stress on Stalin's personality adopted by so many authors, and taken so far here, can lead to a treatment of a huge country with a vast population merely as a conglomeration of objects to be acted upon. In reality, the influences and pressures on people were often diverse and contradictory, so that choices had to be made. These were simply not under Stalin's control at all times. One intriguing aspect of the book is the suggestion, never made explicit, that Stalin firmly believed in the existence of enemies around him. This is an essential part of the paranoid diagnosis, repeated and refined by Rancour. If Stalin believed in the guilt, in some sense, of Marshal Tukhachevskii et al. (though sometimes Rancour suggests the opposite), then a picture emerges not of a ruthless dictator coldly plotting the exter- mination of actual and potential opposition, but of a fear-ridden, tormented man lashing out in panic against a threat he believed to real and immediate. -

Kronstadt and Counterrevolution, Part 2 4

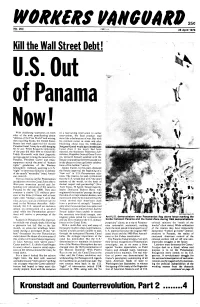

WfJ/iNE/iS ",IN'IJ,I/t, 25¢ No. 203 :~: .~lJ 28 April 1978 Kill the Wall Street Debt! it • • u " o ow! With doddering warhorses on both of a face-saving reservation to earlier sides of the aisle pontificating about reservations, the final product read "defense of the Free World" and waving more like a declaration of war. But with rhetorical Big Sticks, the United States his political career at stake and after Senate last week approved the second blustering about how his 9,000-man Panama£anal Treaty by a cliff-hanging cNat.WQaJ Quard wO.I,lJd.~ve,.nva4ed.!he 68-32 vote. While Reaganite opponents Canal Zone if the treaty had been of the pact did their best to sound like rejected, the shameless Panamian /ider Teddy Roosevelt with their jingoistic maximo, Brigadier General OmarTorri ravings against turning the canal over to jos, declared himself satisfied with the Panama, President Carter and treaty Senate vote and had free beer passed out supporters struck the pose of "human in the plazas to liven up listless celebra rights" gendarmes of the Western tions of his hollow "victory." hemisphere, endlessly asserting a U.S. Jimmy Carter, for his part, declared "right" to intervene militarily in defense the Senate approval the beginning of a of the canal's "neutrality" (read, Ameri "new era" in U.S.-Panamanian rela can control). tions. The treaties, he said, symbolized The two treaties callfor Panamanian that the U.S. would deal with "the small jurisdiction over the Canal Zone after a nations of the world, on the basis of three-year transition period and for mutual respect and partnership" (New handing over operation of the canal to York Times, 19 April). -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Kelly. 2012. Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9830349 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Kelly Scott Johnson All rights reserved Professor Ruth R. Wisse Kelly Scott Johnson Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin Abstract The thesis represents the first complete academic biography of a Jewish clockmaker, warrior poet and Anarchist named Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard's experience was both typical and unique for a Jewish man of his era. It included four immigrations, two revolutions, numerous pogroms, a world war and, far less commonly, an assassination. The latter gained him fleeting international fame in 1926, when he killed the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura in Paris in retribution for pogroms perpetrated during the Russian Civil War (1917-20). After a contentious trial, a French jury was sufficiently convinced both of Schwarzbard's sincerity as an avenger, and of Petliura's responsibility for the actions of his armies, to acquit him on all counts. Mostly forgotten by the rest of the world, the assassin has remained a divisive figure in Jewish-Ukrainian relations, leading to distorted and reductive descriptions his life. -

Universum Historiae Et Archeologiae 2020. Vol. 3 (28). Lib. 1 The

doi 10.15421/2620032801 ISSN 2664–9950 (Print) ISSN 2707–6385 (Online) Universum Historiae et Archeologiae 2020. Vol. 3 (28). Lib. 1 The Universe of History and Archeology 2020. Vol. 3 (28). Issue 1 Універсум історії та археології 2020. Т. 3 (28). Вип. 1 Универсум истории и археологии 2020. Т. 3 (28). Вып. 1 Дніпро 2020 УДК 93/94+902 LCC D 1 Друкується за рішенням вченої ради Дніпровського національного університету імені Олеся Гончара згідно з планом видань на 2020 рік Universum Historiae et Archeologiae = The Universe of History and Archeology = Універсум історії та археології = Универсум истории и археологии. Dnipro, 2020. Vol. 3 (28). Issue 1. DOI: 10.15421/2620032801. Release contains a variety of materials research on topical issues in the history of Ukraine and World History. Considerable space is devoted to recent theoretical and methodological, historiographical and archaeological investigation. This issue of the journal will be of interest to academic staff of higher education institutions, research institutions scholars, doctoral students, graduate students and students in history. Universum Historiae et Archeologiae = The Universe of History and Archeology = Універсум історії та археології = Универсум истории и археологии. Дніпро, 2020. Т. 3 (28). Вип. 1. DOI: 10.15421/2620032801. Випуск містить різноманітні матеріали наукових досліджень з актуальних проблем історії України та всесвітньої історії. Значне місце відведено результатам останніх теоретико- методологічних, історіографічних та археологічних досліджень. Становитиме інтерес для науково-педагогічних працівників ЗВО, науковців академічних установ, докторантів, аспірантів та студентів у історичній царині. Universum Historiae et Archeologiae = The Universe of History and Archeology = Універсум історії та археології = Универсум истории и археологии. Днипро, 2020. Т. -

Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21 Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21

Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21 Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21 Colin Darch First published 2020 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Colin Darch 2020 The right of Colin Darch to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3888 0 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3887 3 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0526 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0528 7 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0527 0 EPUB eBook Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England For my grandchildren Historia scribitur ad narrandum, non ad probandum – Quintilian Contents List of Maps viii List of Abbreviations ix Acknowledgements x 1. The Deep Roots of Rural Discontent: Guliaipole, 1905–17 1 2. The Turning Point: Organising Resistance to the German Invasion, 1918 20 3. Brigade Commander and Partisan: Makhno’s Campaigns against Denikin, January–May 1919 39 4. Betrayal in the Heat of Battle? The Red–Black Alliance Falls Apart, May–September 1919 54 5. The Long March West and the Battle at Peregonovka 73 6. Red versus White, Red versus Green: The Bolsheviks Assert Control 91 7. The Last Act: Alliance at Starobel’sk, Wrangel’s Defeat, and Betrayal at Perekop 108 8. The Bitter Politics of the Long Exile: Romania, Poland, Germany, and France, 1921–34 128 9. -

Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM): a Case Study of an Urban

REVOLUTIONARY ACTION MOVEMENT (RAM) : A CASE STUDY OF AN URBAN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT IN WESTERN CAPITALIST SOCIETY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS By Maxwell C . Stanford DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ATLANTA, GEORGIA MAY 1986 ABSTRACT POLITICAL SCIENCE STANFORD, MAXWELL CURTIS B .A ., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS, 1976 RevolutionarZ Action Movement (RAM) : A Case Study of an Urban Revolution- ary Movement in Western Cap i talist Society Adviser : Professor Lawrence Moss Thesis dated May, 1986 The primary intent of this thesis is to present a political descrip- tive analysis of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), an urban revolu- tionary movement active in the 1960's . An attempt has been made to por tray the historical context, the organization, ideology of the RAM organi- zation and response of the state to the activities of the organization . The thesis presents a methodological approach to developing a para- digm in which the study of urban revolutionary movements is part of a rational analysis . The thesis also explains concepts and theories that are presented later in the text . A review of black radical activity from 1900 to 1960 is given to provide the reader with historical background in- formation of the events and personalities which contributed to the develop- ment of RAM . A comparative analysis is made between urban revolutionary movements in Latin America and the United States in order to show that the RAM organization was part of a worldwide urban phenomenon . The scope of the thesis is to present an analysis of the birth, early beginnings of RAM as a national organization, and Malcolm X's impact on the organization . -

Ukraine, L9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: a Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Fall 2020 Ukraine, l9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe Daniel A. Collins Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Daniel A., "Ukraine, l9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe" (2020). Honors Theses. 553. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/553 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ukraine, 1918-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe by Daniel A. Collins An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in History 12/7/2020 Approved by: Adviser:_____________________________ David Del Testa Second Evaluator: _____________________ Mehmet Dosemeci iii Acknowledgements Above all others I want to thank Professor David Del Testa. From my first oddly specific question about the Austro-Hungarians on the Italian front in my first week of undergraduate, to here, three and a half years later, Professor Del Testa has been involved in all of the work I am proud of. From lectures in Coleman Hall to the Somme battlefield, Professor Del Testa has guided me on my journey to explore World War I and the Interwar Period, which rapidly became my topics of choice. -

The Black Guards

The Black Guards A short account of the Anarchist Black Guards and their suppression by the Bolsheviks in Moscow in 1918 Many Russian anarchists were totally opposed to the institutionalisation of the Red Guards, fighting units that had been created by factory workers in the course of the February and October Revolutions. Indeed Rex A. Wade in his book on the Red Guards points to the strong anarchist input and influence in the Red Guards in the initial phase of the Revolution. Relations between the anarchists and the Bolsheviks had started to deteriorate after the October Revolution, and anarchist delegates to the 2nd Congress of Soviets in December 1917 accused Lenin and his party of red militarism, and that the commissars were only in power at the point of a bayonet. As a result in Moscow, Petrograd and other main centres they made a concerted attempt to set up free fighting units that they called the Black Guard. In 1917 detachments of Black Guards had been set up in the Ukraine, including by Makhno. Nikolai Zhelnesnyakov as to flee Petrograd after the Bolsheviks attempted to arrest him and set up a large group of the Black Guard in the Ukraine. Other Black Guard detachments operating in the Ukraine were led by Mokrousov, Garin with his armoured train, Anatolii Zhelesnyakov, the younger brother of Nikolai, and the detachment led by Seidel and Zhelyabov which defended Odessa and Nikolaev. Another Black Guard detachment was led by Mikhail Chernyak, later active in the Makhnovist counterintelligence. In Vyborg near Petrograd, anarchist workers at the Russian Renault factory set up a Black Guard but it soon merged with a Red Guard that had been created at the factory at the same time. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

VCU Open 2013 Round #7

VCU Open 2013 Round 7 Tossups 1. One play by this author features a man with "all the nations of the old world at war in his veins" arriving to sort out the plot in the final act; that character created by him is the American naval captain Hamlin Kearney. This author wrote a play that includes a Moroccan sheikh who kills Christians until stopped by the lady-explorer Cicely Waynflete and the crusty title guide. In another play by this man, Essie is invited to stay in the new home of a man that Judith Anderson hates, after uncle Peter is hanged, and Westerbridge, New Hampshire is sent into a tizzy when Dick Dudgeon is sentenced to death. In another play by him, a chain of murders leads to the death of Pothinus and then, at the hands of Rufio, Ftatateeta, after one title character finds the other between the paws of the Sphinx and then in a rolled-up carpet. This author of Captain Brassbound's Conversion included John Burgoyne as an antagonist in his The Devil's Disciple; those two dramas, along with Caesar and Cleopatra, make up his Three Plays for Puritans. For 10 points, name this playwright of Man and Superman and Pygmalion. ANSWER: George Bernard Shaw [or GBS] 019-13-64-07101 2. Magallis and Damophilus of Enna are particularly blamed for behavior leading to an event of this type by Diodorus Siculus. One of these events was organized by a Syrian man who had entertained party guests by breathing fire and making humorous prophecies about an event of this kind. -

Global Anti-Anarchism: the Origins of Ideological Deportation and the Suppression of Expression

Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 7 Winter 2012 Global Anti-Anarchism: The Origins of ideological Deportation and the Suppression of Expression Julia Rose Kraut New York University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Immigration Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Kraut, Julia Rose (2012) "Global Anti-Anarchism: The Origins of ideological Deportation and the Suppression of Expression," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 19 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol19/iss1/7 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Global Anti-Anarchism: The Origins of Ideological Deportation and the Suppression of Expression JULIA ROSE KRAUT* ABSTRACT On September 6, 1901, a self-proclaimed anarchist named Leon Czolgosz fatally shot President William McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. This paper places the suppression of anarchists and the exclusion and deportation of foreigners in the aftermath of the "shot that shocked the world" within the context of international anti-anarchist efforts, and reveals that President McKinley's assassination successfully pulled the United States into an existing global conversation over how to combat anarchist violence. This paper argues that these anti-anarchistrestrictions and the suppression of expression led to the emergence of a "free speech consciousness" among anarchists,and others, and to the formation of the Free Speech League, predecessor of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).