Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM): a Case Study of an Urban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church Model

Women Who Lead Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church model: ● “A predominantly female membership with a predominantly male clergy” (159) Competition: ● “Black Panther Party...gave the women of the BPP far more opportunities to lead...than any of its contemporaries” (161) “We Want Freedom” (pt. 2) Invisibility does not mean non existent: ● “Virtually invisible within the hierarchy of the organization” (159) Sexism does not exist in vacuum: ● “Gender politics, power dynamics, color consciousness, and sexual dominance” (167) “Remembering the Black Panther Party, This Time with Women” Tanya Hamilton, writer and director of NIght Catches Us “A lot of the women I think were kind of the backbone [of the movement],” she said in an interview with Michel Martin. Patti remains the backbone of her community by bailing young men out of jail and raising money for their defense. “Patricia had gone on to become a lawyer but that she was still bailing these guys out… she was still their advocate… showing up when they had their various arraignments.” (NPR) “Although Night Catches Us, like most “war” films, focuses a great deal on male characters, it doesn’t share the genre’s usual macho trappings–big explosions, fast pace, male bonding. Hamilton’s keen attention to minutia and everydayness provides a strong example of how women directors can produce feminist films out of presumably masculine subject matter.” “In stark contrast, Hamilton brings emotional depth and acuity to an era usually fetishized with depictions of overblown, tough-guy black masculinity.” In what ways is the Black Panther Party fetishized? What was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense? The Beginnings ● Founded in October 1966 in Oakland, Cali. -

NEGROES with GUNS.Qxd

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NEGROES WITH GUNS: ROB WILLIAMS AND BLACK POWER TELLS THE FASCINATING STORY OF A FORGOTTEN CIVIL RIGHTS FIGURE WHO DARED TO ADVO- CATE ARMED RESISTANCE TO THE VIOLENCE OF Pressroom for more information THE JIM CROW SOUTH. and/or downloadable images: itvs.org/pressroom/ PREMIERES ON PBS'S INDEPENDENT LENS THE EMMY AWARD-WINNING SERIES HOSTED BY EDIE FALCO Program companion website: TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 7, AT 10 PM (CHECK LOCAL LISTINGS) www.pbs.org/independentlens/negroeswithguns/ "I just wasn't going to allow white men to have that much authority over me." CONTACT -Robert Williams CARA WHITE 843/881-1480 (San Francisco)—Taken from the title of Robert Williams's 1962 manifesto entitled Negroes with Guns, NEGROES WITH GUNS: ROB WILLIAMS AND BLACK POWER tells the wrenching story of the [email protected] now-forgotten civil rights activist who dared to challenge not only the Klan-dominated establish- ment in his small North Carolina hometown but also the nonviolence-advocating leadership of the MARY LUGO mainstream Civil Rights Movement. Williams, who had witnessed countless acts of brutality against 770/623-8190 his neighbors, courageously gave public expression to the private philosophy of many African [email protected] Americans-that armed self-defense was both a practical matter of survival and an honorable posi- tion, particularly in the violent racist heart of the Deep South. Featuring a jazz score by Terence RANDALL COLE Blanchard (Barbershop and the films of Spike Lee), NEGROES WITH GUNS combines modern-day 415/356-8383 x254 interviews with rare archival news footage and interviews to tell the story of Williams, the forefa- [email protected] ther of the black power movement and a fascinating, complex man who played a pivotal role in the struggle for respect, dignity and equality for all Americans. -

Contents Perspectives in History Vol

Contents Perspectives in History Vol. 34, 2018-2019 2 Letter from the President Abigail Carr 3 Foreword Abigail Carr 5 The Rise and Fall of Women’s Rights and Equality in Ancient Egypt Abigail Carr 11 The Immortality of Death in Ancient Egypt Nicole Clay 17 Agent Orange: The Chemical Killer Lingers Weston Fowler 27 “Understanding Great Zimbabwe” Samantha Hamilton 33 Different Perspectives in the Civil Rights Movement Brittany Hartung 41 Social Evil: The St. Louis Solution to Prostitution Emma Morris 49 European Influence on the Founding Fathers Travis Roy 55 Bell, Janet Dewart. Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement. New York: New Press, 2018. Josie Hyden 1 Letter from the President The Alpha Beta Phi chapter of Phi Alpha Theta at Northern Kentucky University has been an organization that touched the lives of many of the university’s students. As the President of the chapter during the 2018-2019 school year, it has been my great honor to lead such a determined and hardworking group of history enthusiasts. With these great students, we have put together the following publication of Perspectives in History. In the 34th volume of Perspectives in History, a wide variety of topics throughout many eras of history are presented by some of Northern Kentucky University’s finest students of history. Countless hours of research and dedication have been put into the papers that follow. Without the thoughtful and diligent writers of these pieces, this journal would cease to exist, so we extend our gratitude to those that have shared their work with us. -

The History of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a Curriculum Tool for Afrikan American Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies. Kit Kim Holder University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Holder, Kit Kim, "The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4663. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4663 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES A Dissertation Presented By KIT KIM HOLDER Submitted to the Graduate School of the■ University of Massachusetts in partial fulfills of the requirements for the degree of doctor of education May 1990 School of Education Copyright by Kit Kim Holder, 1990 All Rights Reserved THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966 - 1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES Dissertation Presented by KIT KIM HOLDER Approved as to Style and Content by ABSTRACT THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1971 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 1990 KIT KIM HOLDER, B.A. HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE M.S. BANK STREET SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Directed by: Professor Meyer Weinberg The Black Panther Party existed for a very short period of time, but within this period it became a central force in the Afrikan American human rights/civil rights movements. -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Dissertation As a Partial

Distribution Agreement In presenting this dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non- exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this dissertation. Signature: ____________________________ ______________ Michelle S. Hite Date Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. Hite Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts ___________________________________________________________ Rudolph P. Byrd, Ph.D. Advisor ___________________________________________________________ Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Ph.D. Committee Member ___________________________________________________________ Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: ___________________________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School ____________________ Date Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. Hite M.Sc., University of Kentucky Rudolph P. Byrd, Ph.D. An abstract of A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Emory University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts 2009 Abstract Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 17-1200 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- INDEPENDENT PARTY, ET AL., Petitioners, v. ALEX PADILLA, CALIFORNIA SECRETARY OF STATE, Respondent. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF CITIZENS IN CHARGE AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- --------------------------------- PAUL A. ROSSI Counsel of Record 316 Hill Street Mountville, PA 17554 (717) 961-8978 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the party names INDEPENDENT PARTY and AMERICAN INDEPENDENT PARTY are so sim- ilar to each other that voters will be misled if both of them appeared on the same California ballot. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTION PRESENTED................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................. ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST ............................. 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................................... 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 3 CONCLUSION .................................................... -

Views That Barnes Has Given, Wherein

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Darker Matters: Racial Theorizing through Alternate History, Transhistorical Black Bodies, and Towards a Literature of Black Mecha in the Science Fiction Novels of Steven Barnes Alexander Dumas J. Brickler IV Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DARKER MATTERS: RACIAL THEORIZING THROUGH ALTERNATE HISTORY, TRANSHISTORICAL BLACK BODIES, AND TOWARDS A LITERATURE OF BLACK MECHA IN THE SCIENCE FICTION NOVELS OF STEVEN BARNES By ALEXANDER DUMAS J. BRICKLER IV A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Alexander Dumas J. Brickler IV defended this dissertation on April 16, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jerrilyn McGregory Professor Directing Dissertation Delia Poey University Representative Maxine Montgomery Committee Member Candace Ward Committee Member Dennis Moore Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, I have to give thanks to the Most High. My odyssey through graduate school was indeed a long night of the soul, and without mustard-seed/mountain-moving faith, this journey would have been stymied a long time before now. Profound thanks to my utterly phenomenal dissertation committee as well, and my chair, Dr. Jerrilyn McGregory, especially. From the moment I first perused the syllabus of her class on folkloric and speculative traditions of Black authors, I knew I was going to have a fantastic experience working with her. -

Active Political Parties in Village Elections

YEAR ACTIVE POLITICAL PARTIES IN VILLAGE ELECTIONS 1894 1895 1896 1897 Workingman’s Party People’s Party 1898 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1899 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1900 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1901 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1902 Citizen’s Party Reform Party Independent Party 1903 Citizen’s Party Independent Party 1904 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1905 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1906 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1907 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1908 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1909 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1910 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1911 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1912 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1913 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1914 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1915 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1916 Citizen’s Party Independent Party American Party 1917 Citizen’s Party American Party 1918 Citizen’s Party American Party 1919 Citizen’s Party American Party 1920 Citizen’s Party American Party 1921 Citizen’s Party American Party 1922 Citizen’s Party American Party 1923 Citizen’s Party American Party 1924 Citizen’s Party American Party Independent Party 1925 Citizen’s Party American party 1926 Citizen’s party American Party 1927 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1928 Citizen’s Party American Party 1929 Citizen’s Party American Party 1930 Citizen’s Party American Party 1931 Citizen’s Party American Party 1932 Citizen’s Party American Party 1933 Citizen’s Party American Party 1934 Citizen’s Party American Party 1935 Citizen’s Party American Party 1936 Citizen’s Party Old Citizen’s -

Karenga's Men There, in Campbell Hall. This Was Intended to Stop the Work and Programs of the Black

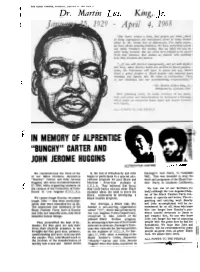

THE BLACK P'"THRR. """0". J'"""V "' ,~, P'CF . ,J: Dr. Martin - II But there comes a time, that. peoPle get tired...tired of being segregated and humiliated; tired of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression. For many years, we have shown amazing patience. We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice. "...If you will protest courageously, and yet with dignity and love, when history books are written in future genera- tions, the historians will have to pause and say, 'there lived a great peoPle--a Black peoPle--who injected new meanir:&g and dignity into the veins of civilization.' This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility." t.1 " --Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Montgomery, Alabama 1956 With pulsating voice, he made mockery of our fears; with convictlon and determinatlon he delivered a Message which made us overcome these fears and march forward with dignity . ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE \'-'I'; ~ f~~ ALPRENTICE CARTER JOHN HUGGINS We commemorate the lives of two In the fall of 1968,Bunchy and John Karenga's men there, in Campbell of our fallen brothers, Alprentice began to participate in a special edu- Hall. This was intended to stop the "Bunchy" Carter and John Jerome cational program for poor Black and work and programs of the Black Pan- Huggins, who were murdered J anuary Mexican -American students at ther Party in Southern California. -

The Iranian Revolution, Past, Present and Future

The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Dr. Zayar Copyright © Iran Chamber Society The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Content: Chapter 1 - The Historical Background Chapter 2 - Notes on the History of Iran Chapter 3 - The Communist Party of Iran Chapter 4 - The February Revolution of 1979 Chapter 5 - The Basis of Islamic Fundamentalism Chapter 6 - The Economics of Counter-revolution Chapter 7 - Iranian Perspectives Copyright © Iran Chamber Society 2 The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Chapter 1 The Historical Background Iran is one of the world’s oldest countries. Its history dates back almost 5000 years. It is situated at a strategic juncture in the Middle East region of South West Asia. Evidence of man’s presence as far back as the Lower Palaeolithic period on the Iranian plateau has been found in the Kerman Shah Valley. And time and again in the course of this long history, Iran has found itself invaded and occupied by foreign powers. Some reference to Iranian history is therefore indispensable for a proper understanding of its subsequent development. The first major civilisation in what is now Iran was that of the Elamites, who might have settled in South Western Iran as early as 3000 B.C. In 1500 B.C. Aryan tribes began migrating to Iran from the Volga River north of the Caspian Sea and from Central Asia. Eventually two major tribes of Aryans, the Persian and Medes, settled in Iran. One group settled in the North West and founded the kingdom of Media. The other group lived in South Iran in an area that the Greeks later called Persis—from which the name Persia is derived. -

The Role of the IMO in the Maritime Governance of Terrorism

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 2002 The role of the IMO in the maritime governance of terrorism Lucio Javier Salonio Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Salonio, Lucio Javier, "The role of the IMO in the maritime governance of terrorism" (2002). World Maritime University Dissertations. 1265. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/1265 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. &EMM WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmo, Sweden THE ROLE OF THE IMO IN THE MARITIME GOVERNANCE OF TERRORISM By LUCIO JAVIER SALONIO Argentina A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In MARITIME AFFAIRS (Maritime Administration) 2002 © Copyright Lucio Salonio, 2002. DECLARATION I certify that all the material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The contents of this dissertation reflect my own personal views and are not necessarily Supervised by: Robert McFarland LCDRU.S. Coast Guard Assessor: Dr. John Liljedhal World Maritime University Co - Assessor: Dr. Gotthard Gauci University of Wales Swansea II DEDICATION My dedication goes to all those minds that in one way or another believe in the confluence of people and the role that International Organizations have in giving to each part of society, even if it be the sole individual, the chance to be included in all our affairs. -

Republican Women and the Gendered Politics of Partisanship

Melanie Susan Gustafson. Women and the Republican Party, 1854-1924. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001. ix + 288 pp. $34.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-252-02688-1. Reviewed by Linda Van Ingen Published on H-Women (June, 2002) Republican Women and the Gendered Politics tions of party politics. In other words, disfran‐ of Partisanship, 1854-1924 chised women were both partisan and nonparti‐ Melanie Gustafson successfully confronts the san players who sought access to the male-domi‐ historical complexity of American women's parti‐ nated institutions of political parties without los‐ sanship in Women and the Republican Party, ing their influence as women uncorrupted by 1854-1924. Her work deepens and enriches the such politics. The resulting portrait of women's field of women's political history in the late nine‐ political history, then, is more complex than pre‐ teenth and early twentieth centuries by bringing viously realized. This book demonstrates how together two seemingly disparate trends in wom‐ much of women's political history is about the en's politics. On the one hand, historians have gendered politics of partisanship. long focused on women's nonpartisan identities in Gustafson develops her analyses with a focus their altruistic reform and suffrage movements. on the Republican Party at the national level. Politics in these studies has been defined broadly From its founding in 1854, through the Progres‐ to include the wide range of women's public activ‐ sive Party challenge in the early twentieth centu‐ ities and the formation of a women's political cul‐ ry, to the height of its success in the 1920s, the Re‐ ture.[1] On the other hand, historians have more publican Party provides a chronological history recently studied women's partisan loyalties and that holds Gustafson's study of women's varied their roles in institutional politics.