NEGROES with GUNS.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Perspectives in History Vol

Contents Perspectives in History Vol. 34, 2018-2019 2 Letter from the President Abigail Carr 3 Foreword Abigail Carr 5 The Rise and Fall of Women’s Rights and Equality in Ancient Egypt Abigail Carr 11 The Immortality of Death in Ancient Egypt Nicole Clay 17 Agent Orange: The Chemical Killer Lingers Weston Fowler 27 “Understanding Great Zimbabwe” Samantha Hamilton 33 Different Perspectives in the Civil Rights Movement Brittany Hartung 41 Social Evil: The St. Louis Solution to Prostitution Emma Morris 49 European Influence on the Founding Fathers Travis Roy 55 Bell, Janet Dewart. Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement. New York: New Press, 2018. Josie Hyden 1 Letter from the President The Alpha Beta Phi chapter of Phi Alpha Theta at Northern Kentucky University has been an organization that touched the lives of many of the university’s students. As the President of the chapter during the 2018-2019 school year, it has been my great honor to lead such a determined and hardworking group of history enthusiasts. With these great students, we have put together the following publication of Perspectives in History. In the 34th volume of Perspectives in History, a wide variety of topics throughout many eras of history are presented by some of Northern Kentucky University’s finest students of history. Countless hours of research and dedication have been put into the papers that follow. Without the thoughtful and diligent writers of these pieces, this journal would cease to exist, so we extend our gratitude to those that have shared their work with us. -

Persecution and Perseverance: Black-White Interracial Relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina

PERSECUTION AND PERSEVERANCE: BLACK-WHITE INTERRACIAL RELATIONSHIPS IN PIEDMONT, NORTH CAROLINA by Casey Moore A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2017 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Aaron Shapiro ______________________________ Dr. David Goldfield ______________________________ Dr. Cheryl Hicks ii ©2017 Casey Moore ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSRACT CASEY MOORE. Persecution and perseverance: Black-White interracial relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina. (Under the direction of DR. AARON SHAPIRO) Although black-white interracial marriage has been legal across the United States since 1967, its rate of growth has historically been slow, accounting for less than eight percent of all interracial marriages in the country by 2010. This slow rate of growth lies in contrast to a large amount of national poll data depicting the liberalization of racial attitudes over the course of the twentieth-century. While black-white interracial marriage has been legal for almost fifty years, whites continue to choose their own race or other races and ethnicities, over black Americans. In the North Carolina Piedmont, this phenomenon can be traced to a lingering belief in the taboo against interracial sex politically propagated in the 1890s. This thesis argues that the taboo surrounding interracial sex between black men and white women was originally a political ploy used after Reconstruction to unite white male voters. In the 1890s, Democrats used the threat of interracial sex to vilify black males as sexual deviants who desired equality and voting rights only to become closer to white females. -

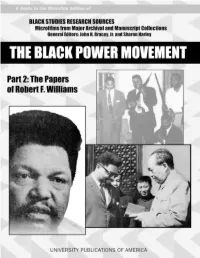

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

Robert F. Williams, "Black Power," and the Roots of the African American Freedom Struggle Author(S): Timothy B

Robert F. Williams, "Black Power," and the Roots of the African American Freedom Struggle Author(s): Timothy B. Tyson Source: The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 2 (Sep., 1998), pp. 540-570 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of Organization of American Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2567750 Accessed: 09-07-2016 03:29 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Organization of American Historians, Oxford University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of American History This content downloaded from 128.210.126.199 on Sat, 09 Jul 2016 03:29:06 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Robert F Williams, "Black Power;' and the Roots of the African American Freedom Struggle Timothy B. Tyson "The childhood of Southerners, white and colored," Lillian Smith wrote in 1949, "has been lived on trembling earth." For one black boy in Monroe, North Carolina, the earth first shook on a Saturday morning in 1936. Standing on the sidewalk on Main Street, Robert Franklin Williams witnessed the battering of an African American woman by a white policeman. -

Black Performance and Cultural Criticism Valerie Lee and E. Patrick Johnson, Series Editors

Black Performance and Cultural Criticism Valerie Lee and E. Patrick Johnson, Series Editors Seniors_Book4print.indb 1 5/28/2009 11:30:56 AM Seniors_Book4print.indb 2 5/28/2009 11:30:56 AM BEYOND LIFT EVERY VOICE AND SING The Culture of Uplift, Identity, and Politics in Black Musical Theater • Paula Marie Seniors The Ohio State University Press Columbus Seniors_Book4print.indb 3 5/28/2009 11:30:56 AM Copyright © 2009 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seniors, Paula Marie. Beyond lift every voice and sing : the culture of uplift, identity, and politics in black musical theater / Paula Marie Seniors. p. cm. — (Black performance and cultural criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1100-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1100-3 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. African Americans in musical theater—History. 2. Musical theater—United States—History. 3. Johnson, James Weldon, 1871–1938. 4. Johnson, J. Rosamond (John Rosamond), 1873–1954. 5. Cole, Bob, 1868–1911. I. Title. ML1711.S46 2009 792.6089'96073—dc22 2008048102 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1100-7) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9198-6) Cover design by Laurence Nozik. Type set in Adobe Sabon. Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Seniors_Book4print.indb 4 5/28/2009 11:30:56 AM This book is dedicated to my scholar activist parents AUDREY PROCTOR SENIORS CLARENCE HENRY SENIORS AND TO MIss PARK SENIORS Their life lessons and love nurtured me. -

Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case Denise Hill A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Media and Journalism. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Barbara Friedman Lois Boynton Trevy McDonald Earnest Perry Ronald Stephens © 2016 Denise Hill ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Denise Hill: Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case (Under the direction of Dr. Barbara Friedman) This dissertation examines how public relations was used by the Committee to Combat Racial Injustice (CCRI), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), North Carolina Governor Luther Hodges, and the United States Information Agency (USIA) in regards to the 1958 kissing case. The kissing case occurred in Monroe, North Carolina when a group of children were playing, including two African American boys, age nine and eight, and a seven-year-old white girl. During the game, the nine-year-old boy and the girl exchanged a kiss. As a result, the police later arrested both boys and charged them with assaulting and molesting the girl. They were sentenced to a reformatory, with possible release for good behavior at age 21. The CCRI launched a public relations campaign to gain the boys’ freedom, and the NAACP implemented public relations tactics on the boys’ behalf. News of the kissing case spread overseas, drawing unwanted international attention to US racial problems at a time when the country was promoting worldwide democracy. -

Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM): a Case Study of an Urban

REVOLUTIONARY ACTION MOVEMENT (RAM) : A CASE STUDY OF AN URBAN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT IN WESTERN CAPITALIST SOCIETY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS By Maxwell C . Stanford DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ATLANTA, GEORGIA MAY 1986 ABSTRACT POLITICAL SCIENCE STANFORD, MAXWELL CURTIS B .A ., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS, 1976 RevolutionarZ Action Movement (RAM) : A Case Study of an Urban Revolution- ary Movement in Western Cap i talist Society Adviser : Professor Lawrence Moss Thesis dated May, 1986 The primary intent of this thesis is to present a political descrip- tive analysis of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), an urban revolu- tionary movement active in the 1960's . An attempt has been made to por tray the historical context, the organization, ideology of the RAM organi- zation and response of the state to the activities of the organization . The thesis presents a methodological approach to developing a para- digm in which the study of urban revolutionary movements is part of a rational analysis . The thesis also explains concepts and theories that are presented later in the text . A review of black radical activity from 1900 to 1960 is given to provide the reader with historical background in- formation of the events and personalities which contributed to the develop- ment of RAM . A comparative analysis is made between urban revolutionary movements in Latin America and the United States in order to show that the RAM organization was part of a worldwide urban phenomenon . The scope of the thesis is to present an analysis of the birth, early beginnings of RAM as a national organization, and Malcolm X's impact on the organization . -

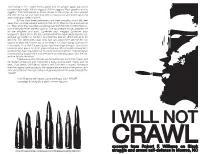

I WILL NOT CRAWL Excerpts from Robert F

“Somebody in the crowd fired a pistol and the people again started to scream hysterically, ‘Kill the niggers! Kill the niggers! Pour gasoline on the niggers!’ The mob started to throw stones on top of my car. So I opened the door of the car and I put one foot on the ground and stood up in the door holding an Italian carbine. All this time three policeman had been standing about fifty feet away from us while we kept waiting in the car for them to come and rescue us. Then when they saw that we were armed and the mob couldn’t take us, two of the policemen started running. One ran straight to me, grabbed me on the shoulder, and said, ‘Surrender your weapon! Surrender your weapon!’ I struck him in the face and knocked him back away from the car and put my carbine in his face, and told him that we didn’t intend to be lynched. The other policeman who had run around the side of the car started to draw his revolver out of the holster. He was hoping to shoot me in the back. They didn’t know that we had more than one gun. One of the students (who was seventeen years old) put a .45 in the policeman’s face and told him that if he pulled out his pistol he would kill him. The policeman started putting his gun back into the holster and backing away from the car, and he fell into the ditch. There was a very old man, an old white man out in the crowd, and he started screaming and crying like a baby, and he kept crying, and he said, ‘God damn, God damn, what is this God damn country coming to that the niggers have got guns, the niggers are armed and the police can’t even arrest them!’ He kept crying and somebody led him away through the crowd.” -from Negroes with Guns, documenting a 1961 NAACP campaign to integrate a public swimming pool. -

Committee Aids Rights Fight in Monroe, NC. Ranks Firm in N. Y. News Strike I-H Pickets Cold to Co. Offers

Committee Aids Rights Fight in t h e MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Monroe, NC. Vol. X X II — No. 52 NEW YORK, N.Y.. MONDAY. DECEMBER 29. 1958 Price 10c By John Thayer In Monroe, destined to go down in history or infamy as the North Carolina town where an eight and nine-year- old Negro boy were sent to reform school because one hac been kissed by a seven-year-old* white girl, the even tenor of v ic t is another question, but merely bringing the assailant to 'Bleakest Detroit Xmas Jim Crow justice was jolted on Dec. 19. On that day a white trial is a victory for the Negro man was arraigned on people of Union County. charges of attempted rape of a Actually, this is the second Negro woman. Local white success registered by the m ili supremacists never expected tant NAACP chapter of Union such a thing to happen, local County. A week previous the authorities had indicated their eviction of Mrs. Thompson and Since Depression Days' intention to reduce the charge her children — solely because or drop it altogether. But their she is the mother of the Negro plans went awry. Whether a lad allegedly kissed by the lily-white jury in this Ku Klux white girl — was prevented. Klan-infested county will con- While outside the South such a thing may seem small potatoes, 200,000 Unemployed it looms large in the Jim Crow Ranks Firm in N. Y. News Strike N.Y. Meeting pattern of life in Monroe. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand ccmer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing theUMI World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820869 Developing a “school” of civil rights lawyers: From the New Deal to the New Frontier White, Vibert Leslie, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by White, Vibert Leslie. All rights reserved. UMI SOON. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, îvîT 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best pcssibic \ /ay from the available copy. -

Black Power, Red Limits: Kwame Nkrumah and American Cold War Responses To

BLACK POWER, RED LIMITS: KWAME NKRUMAH AND AMERICAN COLD WAR RESPONSES TO BLACK EMPOWERMENT STRUGGLES I ~ by ADRIENNE VAN DER VALK A THESIS Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science December 2008 11 "Black Power, Red Limits: Kwame Nkrumah and American Cold War Responses to Black Empowerment Struggles," a thesis prepared by Adrienne van der Valk in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Department of Committee in Charge: Dr. Joseph Lowndes, Chair Dr. Dennis Galvan Dr. Leslie Steeves Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2008 Adrienne van der Valk IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Adrienne van der Valk for the degree of Master ofScience in the Department ofPolitical Science to be taken December 2008 Title: BLACK POWER, RED LIMITS: KWAME NKRUMAH AND AMERICAN COLD WAR RESPON ES TO BLACK EMPOWERMENT STRUGGLES Approved: Scholars ofAmerican history have chronicled ways in which federal level response to the Civil Rights Movement in the United States was influenced by the ideological and strategic conflict between Western and Soviet Bloc countries. This thesis explores the hypothesis that the same Cold War dynamics shown to shape domestic policy toward black liberation were also influential in shaping foreign policy decisions regarding U.S. relations with recently decolonized African countries. To be more specific, the United States was under pressure to demonstrate an agenda of freedom and equality on the world stage, but its tolerance of independent black action was stringently limited when such action included sympathetic association with "radical" factions. -

The Story of Monroe NC

PEOPLE WITH .3~ PEOPLE WITH STRENGTH in Monroe, North Carolina by Truman Nelson "I wish my countrymen to consider, that whatever the human law may be, neither an individual nor a nation can ever com mit the least act of injustice against the obscurest individual without having to pay the penalty for it. A government which deliberately enacts injustice and persists in it, will at length even become the laughing stock of the world." Henry David Thoreau 1 Monroe, North Carolina is the headquarters of the southeastern bri· gades of the Ku Klux Klan. They have built a fine permanent brick building there. The shocking news that pickets were marching in protest against racist wrongs had penetrated deep into South Carolina, (the bor der is scarcely ten miles away), and the mobs watching the pickets were thickening and coagulating into dense cores of violence. Every day there were fresh arrivals of racist whites, more guns were seen, and more roughs to use them. A picket had already been shot in the belly with a pellet gun. It was a grazing shot, and drew no blood. But when the act and the car from which it had come was pointed out to the police, they shrugged it off. Nor did they take notice of the shouted threats and obscenities bubbling up, little hot explosions of hate coming faster and more constant, like the top of a pot of oatmeal coming to a boil...a hate both feeding and consum· ing some five thousand citizens of these United States who could not bear the thought that black people and white people could be t ogether.