Contents Perspectives in History Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEGROES with GUNS.Qxd

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NEGROES WITH GUNS: ROB WILLIAMS AND BLACK POWER TELLS THE FASCINATING STORY OF A FORGOTTEN CIVIL RIGHTS FIGURE WHO DARED TO ADVO- CATE ARMED RESISTANCE TO THE VIOLENCE OF Pressroom for more information THE JIM CROW SOUTH. and/or downloadable images: itvs.org/pressroom/ PREMIERES ON PBS'S INDEPENDENT LENS THE EMMY AWARD-WINNING SERIES HOSTED BY EDIE FALCO Program companion website: TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 7, AT 10 PM (CHECK LOCAL LISTINGS) www.pbs.org/independentlens/negroeswithguns/ "I just wasn't going to allow white men to have that much authority over me." CONTACT -Robert Williams CARA WHITE 843/881-1480 (San Francisco)—Taken from the title of Robert Williams's 1962 manifesto entitled Negroes with Guns, NEGROES WITH GUNS: ROB WILLIAMS AND BLACK POWER tells the wrenching story of the [email protected] now-forgotten civil rights activist who dared to challenge not only the Klan-dominated establish- ment in his small North Carolina hometown but also the nonviolence-advocating leadership of the MARY LUGO mainstream Civil Rights Movement. Williams, who had witnessed countless acts of brutality against 770/623-8190 his neighbors, courageously gave public expression to the private philosophy of many African [email protected] Americans-that armed self-defense was both a practical matter of survival and an honorable posi- tion, particularly in the violent racist heart of the Deep South. Featuring a jazz score by Terence RANDALL COLE Blanchard (Barbershop and the films of Spike Lee), NEGROES WITH GUNS combines modern-day 415/356-8383 x254 interviews with rare archival news footage and interviews to tell the story of Williams, the forefa- [email protected] ther of the black power movement and a fascinating, complex man who played a pivotal role in the struggle for respect, dignity and equality for all Americans. -

Guantanamo Daily Gazette

Tomorrow's flight 727 Water Usage NAS Norfolk, Va. ---------- 8:00 a.m. Wednesday, Jan. 10 Guantanamo Bay 11:00 a.m. noon Usable storage: Kingston, Jamaica 12:30 p.m. 1:00 p.m. 9.20 ML - 66% Guantanamo Bay 2:15 p.m. 3:20 p.m. Goal: 825K NAS Norfolk, Va. 6:15 p.m. Consumption: 956 K See page 3 Guantanamo Daily Gazette Vol. 45 -- No. 153 U.S. Naval Base, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Thursday, January 11, 1990 Obviously.drug smugglers never heard of 0 tolerance level By JOSN C. CORBIN-KRUER around 5p.m., according to MS. I A "The estimated value of the 25 If someone told you that it snows in kilos is $25 million before it hits Guantanamo Bay, would you believe the streets," said an MS spokes them? man. i asu s ic nu htuse ey n a ou nd 5 p ., r ft someone told you that they had An NIS agent cut open one Romania - A transcript released in $2.5 million in Guantanamo Bay, of the bags to test the cocaine for Romania shows that former dictator would you believe them? content "WedoastandardArmed Nicolae Ceausescu personally If someone told you that they Forces Field Test, whenever it ordered his forces to shoot at pro- found 25 kilos of cocaine in Guantan- comes to democracy demonstrators last month. drugs. Without a amo Bay, would you believe them? The transcript shadow of a doubt it came out also shows that Well they Ceausescu warned his top aids during did! positive," he replied. -

BEST WE FORGET © David Dunnico, 2016 BEST WE FORGET

BEST WE FORGET © David Dunnico, 2016 www.dunni.co.uk BEST WE FORGET who starts wars and HOW WAR MEMORIALS HELP US TO FORGET DAVID DUNNICO The Resurrection of the Soldiers Stanley Spencer, 1929 war & remembrance MILLIONS of people died in the First World War. Afterwards, the people who started the war came up with ways to remember the dead that made everyone else forget who had sent them to their deaths. The Cenotaph, the Two Minutes Silence, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, poppies, war memorials, the language we use and the rituals we follow, are all supposed to help us remember people’s sacrifice. But they also help the leaders who sacrificed their own people get away with it. The “war to end all wars” ended a century ago and yet the British have been fighting and remembering to forget, ever since. 7 “A war memorial which has been littered with mistakes since it was created in 1989 may cost £10,000 to fix, a council has said… It is understood errors were made during the process of transferring the names of those killed from memorial plaques around Bodmin to a new monument. A tape recorder, which was used to list the names, is believed to be behind a number of the mistakes. Ann Hicks, chairman of the Cornwall Family History Society, said: ‘They are dishonouring the dead of Cornwall’.” I It’s Later Than You Think “The bells of hell go ting-a-ling-a-ling for you but not for me” – British Airman’s song from World War One THE military mind favours neatness. -

Persecution and Perseverance: Black-White Interracial Relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina

PERSECUTION AND PERSEVERANCE: BLACK-WHITE INTERRACIAL RELATIONSHIPS IN PIEDMONT, NORTH CAROLINA by Casey Moore A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2017 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Aaron Shapiro ______________________________ Dr. David Goldfield ______________________________ Dr. Cheryl Hicks ii ©2017 Casey Moore ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSRACT CASEY MOORE. Persecution and perseverance: Black-White interracial relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina. (Under the direction of DR. AARON SHAPIRO) Although black-white interracial marriage has been legal across the United States since 1967, its rate of growth has historically been slow, accounting for less than eight percent of all interracial marriages in the country by 2010. This slow rate of growth lies in contrast to a large amount of national poll data depicting the liberalization of racial attitudes over the course of the twentieth-century. While black-white interracial marriage has been legal for almost fifty years, whites continue to choose their own race or other races and ethnicities, over black Americans. In the North Carolina Piedmont, this phenomenon can be traced to a lingering belief in the taboo against interracial sex politically propagated in the 1890s. This thesis argues that the taboo surrounding interracial sex between black men and white women was originally a political ploy used after Reconstruction to unite white male voters. In the 1890s, Democrats used the threat of interracial sex to vilify black males as sexual deviants who desired equality and voting rights only to become closer to white females. -

To Review Evidence of a Likely Secret Underground Prison Facility

From: [email protected] Date: June 2, 2009 2:53:54 PM EDT To: [email protected] Cc: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Subject: Our Memorial Day LSI Request of 5/25/2009 3:44:40 P.M. EDT Sirs, We await word on when we can come to Hanoi and accompany you to inspect the prison discussed in our Memorial Day LSI Request of 5/25/2009 3:44:40 P.M. EDT and in the following attached file. As you see below, this file is appropriately entitled, "A Sacred Place for Both Nations." Sincerely, Former U.S. Rep. Bill Hendon (R-NC) [email protected] Former U.S. Rep. John LeBoutillier (R-NY) [email protected] p.s. You would be ill-advised to attempt another faked, immoral and illegal LSI of this prison like the ones you conducted at Bang Liet in spring 1992; Thac Ba in summer 1993 and Hung Hoa in summer 1995, among others. B. H. J. L. A TIME-SENSITIVE MESSAGE FOR MEMBERS OF THE SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON POW/MIA AFFAIRS 1991-1993: SENATOR JOHN F. KERRY, (D-MA), CHAIRMAN SENATOR HARRY REID, (D-NV) SENATOR HERB KOHL (D-WI) SENATOR CHUCK GRASSLEY (R-IA) SENATOR JOHN S. McCAIN, III (R-AZ) AND ALL U.S. SENATORS CONCERNED ABOUT THE SAFETY OF AMERICAN SERVICE PERSONNEL IN INDOCHINA AND THROUGHOUT THE WORLD: http://www.enormouscrime.com "SSC Burn Bag" TWO FORMER GOP CONGRESSMEN REVEAL DAMNING PHOTOS PULLED FROM U.S. SENATE BURN BAG IN 1992; CALL ON SEN. -

Bush Picks 2 Holdovers for Cabinet

Monday, Nov. 21, 1988 Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm 30 Cents N Bush picks 2 holdovers for Cabinet By Christopher Connell President Mikhail Gorbachev The Associated Press comes to the United States and meets with President Reagan. WASHINGTON - President 'T il be there as vice president elect'tJeorge Bush announced of the United States And I expect today he will retain Attorney they’ll be aware they're talking to General Dick Thornburgh and the next president,” Bush said. Education Secretary Lauro F. Bush emphasized the role Cavazos, bringing to three the Thornburgh would have in fight number of Reagan holdovers in ing drugs. his Cabinet. "Drugs are public enemy No. Bush also said he would nomi 1,” said the president-elect. He nate Richard Darman,. former went on to say that Thornburgh White House aide and deputy "w ill work with me to fight drugs Raglnild PInto/MinchMtcr Herald BIG JOB — Employees of the town parks department Treasury secretary, to head the with every tool at our disposal.” Eighth Utilities District Fire Department official said the O ffice of M anagem ent and begin work this morning to remove a tree at 47 N. Elm St. Bush noted that Cavazos, a tree caused moderate damage to the house. From left are Budget. former president of Texas Tech that was knocked over by Sunday’s high winds. An William Wagner, Willie Columbe Jr. and William Gould. Bush said that “ in all likeli University, is the first Hispanic to hood” Thornburgh, Cavazos and hold a Cabinet post but he added, previously announced Treasury "Overriding is Dr. -

The History of This Veterans' Recognition Program Began with an Idea from a Local Vietnam Veteran Activist and a Dance Instruc

The history of this veterans’ recognition program began with an idea from a local Vietnam veteran activist and a dance instructor. Ted Sampley and Mary Beth Dawson wanted a way to pay tribute to the many veterans that have given so much in the continued fight for world peace and freedom. The first Salute “show” was performed in November 2000 at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC to a multitude of veterans and visitors to our nation’s capital. Positive comments after the show prompted Mr. Sampley and Mrs. Dawson to bring the performance back to their hometown of Kinston, North Carolina. In 2001, a committee of Kinston businesses and individuals headed by the Pride of Kinston began planning the veteran celebration. Former US Air Force Sergeant Adrian Cronauer, the deejay better known for “Gooooood Morning, Vietnam” was the emcee during the Tribute Show and kept things lively. Members from the elite group of Tuskeegee Airmen were in attendance during the festivities. One of Kinston’s most distinguished sons, Eugene ‘Red’ McDaniel, was the special speaker at the Memorial Service where all of Lenoir County’s Killed in Action were remembered. Items from the North Carolina boxcar of the French Gratitude Train were on display at the Community Council for the Arts. Purple Heart recipients were recognized during the entire event for their bravery and courage under fire the following year. Artifacts from Michael Blassie’s tomb, more commonly known as the ‘Tomb of the Unknown Soldier’ were on display at the Community Council for the Arts. The Culture Heritage Museum offered a glimpse of black military history during its open house. -

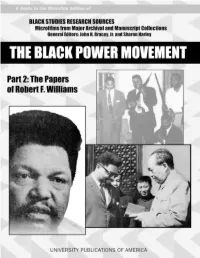

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

China As an Emerging Power

University of Alberta China as an Emerging Power: Issues Related IO TernetordIntegriîy Laura Noce A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies Edmonton, Alberta Fd 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. tue WeUingtori ûttawaON KIAW ûttawaON KlAOlr14 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor subsbntial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This mdy examines China's irredentist ambitions fkom a Realist perspective. It disputes the notion that China is a threat; that the leadership aspires to become a regional hegemon; and that China is using its growing economic power base to develop an offensive miiitary force. Rather, this study contends that China's push to attain temtorial integrity refleas a search for survival and security, both extemaiiy and internally. -

Robert F. Williams, "Black Power," and the Roots of the African American Freedom Struggle Author(S): Timothy B

Robert F. Williams, "Black Power," and the Roots of the African American Freedom Struggle Author(s): Timothy B. Tyson Source: The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 2 (Sep., 1998), pp. 540-570 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of Organization of American Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2567750 Accessed: 09-07-2016 03:29 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Organization of American Historians, Oxford University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of American History This content downloaded from 128.210.126.199 on Sat, 09 Jul 2016 03:29:06 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Robert F Williams, "Black Power;' and the Roots of the African American Freedom Struggle Timothy B. Tyson "The childhood of Southerners, white and colored," Lillian Smith wrote in 1949, "has been lived on trembling earth." For one black boy in Monroe, North Carolina, the earth first shook on a Saturday morning in 1936. Standing on the sidewalk on Main Street, Robert Franklin Williams witnessed the battering of an African American woman by a white policeman. -

Black Performance and Cultural Criticism Valerie Lee and E. Patrick Johnson, Series Editors

Black Performance and Cultural Criticism Valerie Lee and E. Patrick Johnson, Series Editors Seniors_Book4print.indb 1 5/28/2009 11:30:56 AM Seniors_Book4print.indb 2 5/28/2009 11:30:56 AM BEYOND LIFT EVERY VOICE AND SING The Culture of Uplift, Identity, and Politics in Black Musical Theater • Paula Marie Seniors The Ohio State University Press Columbus Seniors_Book4print.indb 3 5/28/2009 11:30:56 AM Copyright © 2009 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seniors, Paula Marie. Beyond lift every voice and sing : the culture of uplift, identity, and politics in black musical theater / Paula Marie Seniors. p. cm. — (Black performance and cultural criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1100-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1100-3 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. African Americans in musical theater—History. 2. Musical theater—United States—History. 3. Johnson, James Weldon, 1871–1938. 4. Johnson, J. Rosamond (John Rosamond), 1873–1954. 5. Cole, Bob, 1868–1911. I. Title. ML1711.S46 2009 792.6089'96073—dc22 2008048102 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1100-7) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9198-6) Cover design by Laurence Nozik. Type set in Adobe Sabon. Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Seniors_Book4print.indb 4 5/28/2009 11:30:56 AM This book is dedicated to my scholar activist parents AUDREY PROCTOR SENIORS CLARENCE HENRY SENIORS AND TO MIss PARK SENIORS Their life lessons and love nurtured me. -

Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case Denise Hill A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Media and Journalism. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Barbara Friedman Lois Boynton Trevy McDonald Earnest Perry Ronald Stephens © 2016 Denise Hill ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Denise Hill: Public Relations, Racial Injustice, and the 1958 North Carolina Kissing Case (Under the direction of Dr. Barbara Friedman) This dissertation examines how public relations was used by the Committee to Combat Racial Injustice (CCRI), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), North Carolina Governor Luther Hodges, and the United States Information Agency (USIA) in regards to the 1958 kissing case. The kissing case occurred in Monroe, North Carolina when a group of children were playing, including two African American boys, age nine and eight, and a seven-year-old white girl. During the game, the nine-year-old boy and the girl exchanged a kiss. As a result, the police later arrested both boys and charged them with assaulting and molesting the girl. They were sentenced to a reformatory, with possible release for good behavior at age 21. The CCRI launched a public relations campaign to gain the boys’ freedom, and the NAACP implemented public relations tactics on the boys’ behalf. News of the kissing case spread overseas, drawing unwanted international attention to US racial problems at a time when the country was promoting worldwide democracy.