Black Power, Red Limits: Kwame Nkrumah and American Cold War Responses To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEGROES with GUNS.Qxd

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NEGROES WITH GUNS: ROB WILLIAMS AND BLACK POWER TELLS THE FASCINATING STORY OF A FORGOTTEN CIVIL RIGHTS FIGURE WHO DARED TO ADVO- CATE ARMED RESISTANCE TO THE VIOLENCE OF Pressroom for more information THE JIM CROW SOUTH. and/or downloadable images: itvs.org/pressroom/ PREMIERES ON PBS'S INDEPENDENT LENS THE EMMY AWARD-WINNING SERIES HOSTED BY EDIE FALCO Program companion website: TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 7, AT 10 PM (CHECK LOCAL LISTINGS) www.pbs.org/independentlens/negroeswithguns/ "I just wasn't going to allow white men to have that much authority over me." CONTACT -Robert Williams CARA WHITE 843/881-1480 (San Francisco)—Taken from the title of Robert Williams's 1962 manifesto entitled Negroes with Guns, NEGROES WITH GUNS: ROB WILLIAMS AND BLACK POWER tells the wrenching story of the [email protected] now-forgotten civil rights activist who dared to challenge not only the Klan-dominated establish- ment in his small North Carolina hometown but also the nonviolence-advocating leadership of the MARY LUGO mainstream Civil Rights Movement. Williams, who had witnessed countless acts of brutality against 770/623-8190 his neighbors, courageously gave public expression to the private philosophy of many African [email protected] Americans-that armed self-defense was both a practical matter of survival and an honorable posi- tion, particularly in the violent racist heart of the Deep South. Featuring a jazz score by Terence RANDALL COLE Blanchard (Barbershop and the films of Spike Lee), NEGROES WITH GUNS combines modern-day 415/356-8383 x254 interviews with rare archival news footage and interviews to tell the story of Williams, the forefa- [email protected] ther of the black power movement and a fascinating, complex man who played a pivotal role in the struggle for respect, dignity and equality for all Americans. -

Contents Perspectives in History Vol

Contents Perspectives in History Vol. 34, 2018-2019 2 Letter from the President Abigail Carr 3 Foreword Abigail Carr 5 The Rise and Fall of Women’s Rights and Equality in Ancient Egypt Abigail Carr 11 The Immortality of Death in Ancient Egypt Nicole Clay 17 Agent Orange: The Chemical Killer Lingers Weston Fowler 27 “Understanding Great Zimbabwe” Samantha Hamilton 33 Different Perspectives in the Civil Rights Movement Brittany Hartung 41 Social Evil: The St. Louis Solution to Prostitution Emma Morris 49 European Influence on the Founding Fathers Travis Roy 55 Bell, Janet Dewart. Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement. New York: New Press, 2018. Josie Hyden 1 Letter from the President The Alpha Beta Phi chapter of Phi Alpha Theta at Northern Kentucky University has been an organization that touched the lives of many of the university’s students. As the President of the chapter during the 2018-2019 school year, it has been my great honor to lead such a determined and hardworking group of history enthusiasts. With these great students, we have put together the following publication of Perspectives in History. In the 34th volume of Perspectives in History, a wide variety of topics throughout many eras of history are presented by some of Northern Kentucky University’s finest students of history. Countless hours of research and dedication have been put into the papers that follow. Without the thoughtful and diligent writers of these pieces, this journal would cease to exist, so we extend our gratitude to those that have shared their work with us. -

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE the COLONIAL CONTEXT: the BIRTH of BANGLADESH in Retrospectt

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE THE COLONIAL CONTEXT: THE BIRTH OF BANGLADESH IN RETROSPECTt By VedP. Nanda* I. INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistan War in December 1971, the independent nation-state of Bangladesh was born.' Within the next four months, more than fifty countries had formally recognized the new nation.2 As India's military intervention was primarily responsible for the success of the secessionist movement in what was then known as East Pakistan, and for the creation of a new political entity on the inter- national scene,3 many serious questions stemming from this historic event remain unresolved for the international lawyer. For example: (1) What is the continuing validity of Article 2 (4) of the United Nations Charter?4 (2) What is the current status of the doctrine of humanita- rian intervention in international law?5 (3) What action could the United Nations have taken to avert the Bangladesh crisis?6 (4) What measures are necessary to prevent such tragic occurrences in the fu- ture?7 and (5) What relationship exists between the principle of self- "- This paper is an adapted version of a chapter that will appear in Y. ALEXANDER & R. FRIEDLANDER, SELF-DETERMINATION (1979). * Professor of Law and Director of the International Legal Studies Program, Univer- sity of Denver Law Center. 1. See generally BANGLADESH: CRISIS AND CONSEQUENCES (New Delhi: Deen Dayal Research Institute 1972); D. MANKEKAR, PAKISTAN CUT TO SIZE (1972); PAKISTAN POLITI- CAL SYSTEM IN CRISIS: EMERGENCE OF BANGLADESH (S. Varma & V. Narain eds. 1972). 2. Ebb Tide, THE ECONOMIST, April 8, 1972, at 47. -

H-Diplo Article Review Forum Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux Published on 16 May 2016

H-Diplo Article Review 20 16 H-Diplo Article Review Editors: Thomas Maddux H-Diplo and Diane Labrosse H-Diplo Article Reviews Web and Production Editor: George Fujii No. 614 An H-Diplo Article Review Forum Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux Published on 16 May 2016 H-Diplo Forum on “Beyond and Between the Cold War Blocs,” Special Issue of The International History Review 37:5 (December 2015): 901-1013. Introduction by Janick Marina Schaufelbuehl, University of Lausanne; Sandra Bott University of Lausanne; Jussi Hanhimäki, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies; and Marco Wyss, University of Chichester Reviewed by: Anne Deighton, The University of Oxford Juergen Dinkel, Justus-Liebig-University Wen-Qing Ngoei, Northwestern University Johanna Rainio-Niemi, University of Helsinki, Finland URL: http://tiny.cc/AR614 Introduction1 by Janick Marina Schaufelbuehl, Sandra Bott, Jussi Hanhimäki, and Marco Wyss2 “Non-Alignment, the Third Force, or Fence-Sitting: Independent Pathways in the Cold War” n his recollection of recent events such as the Bandung Conference, the Soviet proposals for a unified and neutralised Germany, and the signing of the Austrian Treaty, veteran journalist Hanson W. Baldwin Iwrote in the New York Times in May 1955 that these ‘and half a dozen other developments in Europe and 1 H-Diplo would like to thanks Professor Andrew Williams, editor of IHR, and the four authors of this introduction, for granting us permission to publish this review. It original appeared as “Janick Marina Schaufelbuehl, Sandra Bott, Jussi Hanhimäki, and Marco Wyss, “Non-Alignment, the Third Force, or Fence-Sitting: Independent Pathways in the Cold War.” The International History Review 37:5 (December 2015): 901-911. -

Persecution and Perseverance: Black-White Interracial Relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina

PERSECUTION AND PERSEVERANCE: BLACK-WHITE INTERRACIAL RELATIONSHIPS IN PIEDMONT, NORTH CAROLINA by Casey Moore A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2017 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Aaron Shapiro ______________________________ Dr. David Goldfield ______________________________ Dr. Cheryl Hicks ii ©2017 Casey Moore ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSRACT CASEY MOORE. Persecution and perseverance: Black-White interracial relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina. (Under the direction of DR. AARON SHAPIRO) Although black-white interracial marriage has been legal across the United States since 1967, its rate of growth has historically been slow, accounting for less than eight percent of all interracial marriages in the country by 2010. This slow rate of growth lies in contrast to a large amount of national poll data depicting the liberalization of racial attitudes over the course of the twentieth-century. While black-white interracial marriage has been legal for almost fifty years, whites continue to choose their own race or other races and ethnicities, over black Americans. In the North Carolina Piedmont, this phenomenon can be traced to a lingering belief in the taboo against interracial sex politically propagated in the 1890s. This thesis argues that the taboo surrounding interracial sex between black men and white women was originally a political ploy used after Reconstruction to unite white male voters. In the 1890s, Democrats used the threat of interracial sex to vilify black males as sexual deviants who desired equality and voting rights only to become closer to white females. -

Non-Alignment and the United States

Robert B. Rakove. Kennedy, Johnson, and the Nonaligned World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. 315 pp. $31.99, paper, ISBN 978-1-107-44938-1. Reviewed by Simon Stevens Published on H-1960s (August, 2014) Commissioned by Zachary J. Lechner (Centenary College of Louisiana) The central historical problem that Robert B. of a policy of “engagement” of the “nonaligned Rakove sets out to solve in Kennedy, Johnson, and world.” The subsequent souring of relations was a the Nonaligned World is how to explain the re‐ consequence of the abandonment of that ap‐ markable transformation in the relationship be‐ proach under Lyndon Johnson. Central to tween the United States and much of the postcolo‐ Rakove’s argument is the distinction between nial world over the course of the 1960s. The assas‐ Kennedy’s approach to states in the Third World sination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 was met with that were “aligned” in the Cold War and those that genuine grief in many postcolonial states, reflect‐ were “non-aligned.” Common historiographic ing the positive and hopeful light in which the characterizations of Kennedy’s policy toward the United States under Kennedy had been widely Third World as aggressive and interventionist viewed. And yet by the second half of the decade, have failed to appreciate the significance of this the United States “had come to be seen not as an distinction, Rakove suggests. In the cases of states ally to Third World aspirations but as a malevo‐ that the U.S. government perceived to be already lent foe. Polarizing accusatory rhetoric unusual in aligned with the West, especially in Latin America the early 1960s became unremarkable by the and Southeast Asia, the Kennedy administration decade’s end, emerging as a lasting feature of was intolerant of changes that might endanger world politics, a recognizable precursor to con‐ that alignment, and pursued forceful interven‐ temporary denunciations of the United States” (p. -

African Union Union Africaine

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: www.au.int DIRECTORATE OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION PRESS RELEASE Nº051/2018 Deputy Chairperson of the African Union Commission kicks off official visit to Cuba; pays respect to the late Fidel Castro Havana, Cuba, 11th April 2018: The Deputy Chairperson of the African Union Commission, Amb. Kwesi Quartey is in Havana, Cuba for a four day official visit. On arrival, the Deputy Chairperson visited Fidel Castro's mausoleum in Santiago de Cuba city, for a wreath laying and remembrance ceremony, to pay respects to the legendary revolutionary leader. He also signed the condolences book. Amb. Kwesi hailed Castro’s support to Africa during the liberation movements in the continent reiterating the deep-seated historical ties between the African Union and Cuba. In the formative years of Africa’s liberation, Castro met Africa’s celebrated leaders such as Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Nelson Mandela of South Africa, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, Sam Nujoma of Namibia and Muammar Gaddafi of Libya. “Castro’s legacy will be cherished in our hearts for generations to come following the solidarity and generosity he extended to Africa during the anti-colonial struggles and post-colonial era,” he stated. Cuba reliably supported the liberation struggles in countries such as Angola, South Africa and Ethiopia and has continued to offer Cuban troops to serve in several African states. Further, the Deputy Chairperson, while expressing gratitude to Cuba for the existing cooperation and assistance in several African states, particularly in the education and health sectors, highlighted Cuba as an enviable model to follow in terms of investments in the people. -

Cold War History the Rise and Fall of the 'Soviet Model of Development'

This article was downloaded by: [LSE Library] On: 30 September 2013, At: 11:04 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Cold War History Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcwh20 The rise and fall of the ‘Soviet Model of Development’ in West Africa, 1957–64 Alessandro Iandolo a a St Antony's College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK Published online: 14 May 2012. To cite this article: Alessandro Iandolo (2012) The rise and fall of the ‘Soviet Model of Development’ in West Africa, 1957–64, Cold War History, 12:4, 683-704 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2011.649255 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

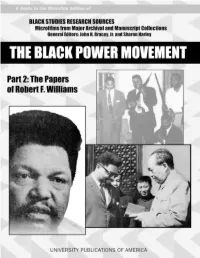

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

America's War in Angola, 1961-1976 Alexander Joseph Marino University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2015 America's War in Angola, 1961-1976 Alexander Joseph Marino University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Marino, Alexander Joseph, "America's War in Angola, 1961-1976" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1167. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1167 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. America’s War in Angola, 1961-1976 America’s War in Angola, 1961-1976 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Alexander J. Marino University of California, Santa Barbara Bachelor of Arts in History, 2008 May 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council ______________________________________ Dr. Randall B. Woods Thesis Director ______________________________________ Dr. Andrea Arrington Committee Member ______________________________________ Dr. Alessandro Brogi Committee Member ABSTRACT A study of the role played by the United States in Angola’s War of Independence and the Angolan Civil War up to 1976. DEDICATION To Lisa. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ -

REVIEW ESSAY Patrice Lumumba: the Evolution of an Évolué

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 16, Issue 2 | March 2016 REVIEW ESSAY Patrice Lumumba: The Evolution of an Évolué CHRISTOPHER R. COOK Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja. 2014. Patrice Lumumba. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. 164 pp. Leo Zeilig. 2015. Patrice Lumumba: Africa’s Lost Leader. London: Hause Publishing. 182 pp. Patrice Lumumba remains an inspirational figure to Congolese and peoples across the developing world for his powerful articulation of economic and political self- determination. But who was the real Lumumba? There are competing myths: for the left he was a messianic messenger of Pan-Africanism; for the right he was angry, unstable and a Communist. He did not leave behind an extensive body of writings to sift through, ponder or analyze. The official canon of his work is short and includes such items as his June 30, 1960 Independence Day speech and the last letter to his wife shortly before his execution. The Patrice Lumumba, the one celebrated in Raoul Peck’s film Lumumba, la mort d’un prophéte does not start to find his own voice until his attendance at the December 1958 First All Africans Peoples’ Conference which leaves him only tenty- five months on the world stage before his death at the age of thirty-five. While there have been other biographies and works on his life, much of it is now out of print or not available in English, Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja’s Patrice Lumumba and Leo Zeilig’s Lumumba: Africa’s Lost Leader have attempted to fill in this biographical vacuum with sympathetic, accessible, and highly readable introductory texts. -

Gender and Decolonization in the Congo

GENDER AND DECOLONIZATION IN THE CONGO 9780230615571_01_prexiv.indd i 6/11/2010 9:30:52 PM This page intentionally left blank GENDER AND DECOLONIZATION IN THE CONGO THE LEGACY OF PATRICE LUMUMBA Karen Bouwer 9780230615571_01_prexiv.indd iii 6/11/2010 9:30:52 PM GENDER AND DECOLONIZATION IN THE CONGO Copyright © Karen Bouwer, 2010. All rights reserved. First published in 2010 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978–0–230–61557–1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bouwer, Karen. Gender and decolonization in the Congo : the legacy of Patrice Lumumba / Karen Bouwer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–230–61557–1 (hardback) 1. Lumumba, Patrice, 1925–1961—Political and social views. 2. Lumumba, Patrice, 1925–1961—Relations with women. 3. Lumumba, Patrice, 1925–1961—Influence. 4. Sex role—Congo (Democratic Republic)—History—20th century. 5. Women—Political activity— Congo (Democratic Republic)—History—20th century. 6. Decolonization—Congo (Democratic Republic)—History—20th century. 7. Congo (Democratic Republic)—Politics and government— 1960–1997. 8. Congo (Democratic Republic)—Social conditions—20th century.