John D Ue ■An Oral History Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEGROES with GUNS.Qxd

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NEGROES WITH GUNS: ROB WILLIAMS AND BLACK POWER TELLS THE FASCINATING STORY OF A FORGOTTEN CIVIL RIGHTS FIGURE WHO DARED TO ADVO- CATE ARMED RESISTANCE TO THE VIOLENCE OF Pressroom for more information THE JIM CROW SOUTH. and/or downloadable images: itvs.org/pressroom/ PREMIERES ON PBS'S INDEPENDENT LENS THE EMMY AWARD-WINNING SERIES HOSTED BY EDIE FALCO Program companion website: TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 7, AT 10 PM (CHECK LOCAL LISTINGS) www.pbs.org/independentlens/negroeswithguns/ "I just wasn't going to allow white men to have that much authority over me." CONTACT -Robert Williams CARA WHITE 843/881-1480 (San Francisco)—Taken from the title of Robert Williams's 1962 manifesto entitled Negroes with Guns, NEGROES WITH GUNS: ROB WILLIAMS AND BLACK POWER tells the wrenching story of the [email protected] now-forgotten civil rights activist who dared to challenge not only the Klan-dominated establish- ment in his small North Carolina hometown but also the nonviolence-advocating leadership of the MARY LUGO mainstream Civil Rights Movement. Williams, who had witnessed countless acts of brutality against 770/623-8190 his neighbors, courageously gave public expression to the private philosophy of many African [email protected] Americans-that armed self-defense was both a practical matter of survival and an honorable posi- tion, particularly in the violent racist heart of the Deep South. Featuring a jazz score by Terence RANDALL COLE Blanchard (Barbershop and the films of Spike Lee), NEGROES WITH GUNS combines modern-day 415/356-8383 x254 interviews with rare archival news footage and interviews to tell the story of Williams, the forefa- [email protected] ther of the black power movement and a fascinating, complex man who played a pivotal role in the struggle for respect, dignity and equality for all Americans. -

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in Mccomb, Mississippi, 1928-1964

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in McComb, Mississippi, 1928-1964 Alec Ramsay-Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 1, 2016 Advised by Professor Howard Brick For Dana Lynn Ramsay, I would not be here without your love and wisdom, And I miss you more every day. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: McComb and the Beginnings of Voter Registration .......................... 10 Chapter Two: SNCC and the 1961 McComb Voter Registration Drive .................. 45 Chapter Three: The Aftermath of the McComb Registration Drive ........................ 78 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 102 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 119 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have done this without my twin sister Hunter Ramsay-Smith, who has been a constant source of support and would listen to me rant for hours about documents I would find or things I would learn in the course of my research for the McComb registration -

Contents Perspectives in History Vol

Contents Perspectives in History Vol. 34, 2018-2019 2 Letter from the President Abigail Carr 3 Foreword Abigail Carr 5 The Rise and Fall of Women’s Rights and Equality in Ancient Egypt Abigail Carr 11 The Immortality of Death in Ancient Egypt Nicole Clay 17 Agent Orange: The Chemical Killer Lingers Weston Fowler 27 “Understanding Great Zimbabwe” Samantha Hamilton 33 Different Perspectives in the Civil Rights Movement Brittany Hartung 41 Social Evil: The St. Louis Solution to Prostitution Emma Morris 49 European Influence on the Founding Fathers Travis Roy 55 Bell, Janet Dewart. Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement. New York: New Press, 2018. Josie Hyden 1 Letter from the President The Alpha Beta Phi chapter of Phi Alpha Theta at Northern Kentucky University has been an organization that touched the lives of many of the university’s students. As the President of the chapter during the 2018-2019 school year, it has been my great honor to lead such a determined and hardworking group of history enthusiasts. With these great students, we have put together the following publication of Perspectives in History. In the 34th volume of Perspectives in History, a wide variety of topics throughout many eras of history are presented by some of Northern Kentucky University’s finest students of history. Countless hours of research and dedication have been put into the papers that follow. Without the thoughtful and diligent writers of these pieces, this journal would cease to exist, so we extend our gratitude to those that have shared their work with us. -

Free Expression and Intellectual Diversity How Florida Universities Currently Measure Up

POLICY BRIEF Free Expression and Intellectual Diversity How Florida Universities Currently Measure Up William Mattox Director of the J. Stanley Marshall Center for Educational Options iddlebury College. University of California, Berkeley. Evergreen State. MClaremont McKenna. Yale. The list of academic institutions rocked in recent months by (sometimes violent) speech-squelching protests is not pretty. And combined with growing concerns about high student debt and sagging job prospects for many new graduates, these efforts to thwart campus discourse are causing many people – for the first time ever – to question whether higher education is truly worth the investment it requires. www.jamesmadison.org | 1 For example, a 2017 survey by the Pew Research Center found campus craziness presents an opportunity for our state. For if the that 58 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning indepen- Florida higher education system were to become a haven for free dents now believe colleges and universities are having a negative expression and viewpoint diversity – and to become known as effect on the direction of our country. This represents a whop- such – our universities would be very well positioned to meet the ping 21 percent shift since 2015 (when 37 percent of center-right growing demand for intellectually-serious academic study at an Americans viewed the performance of higher education institu- affordable cost. tions negatively).1 In fact, a major 2013 report said as much. Growing skepticism about the current direction of American In 2013, the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA) higher education isn’t just found among those on the center-right. produced a comprehensive report on the state of higher education For example, a center-left New York University professor named in Florida (with assistance from The James Madison Institute). -

Voter Education Project |L\Rr, Secured for North Carolina Durham Man Is Named To

Watts HillPredicts New Era Negro Colleges In NCC Address '*\u25a0 A. L "? " (i 'S TrMflr"- . Voter Education Project |L\Rr, Secured For North Carolina Durham Man Is Named to \u25a0 <3? </* Director Post ?3it Carpila The formation of a North administrators and of trustees, Watts Hill Jr., Carolina Voter Education Pro- COMMENCEMENT PROCES- cession of VOLUME 44 No. 21 DURHAM. N. C. SATURDAY, JUNE 3, 1967 PRICE: 20c SION?Dr. Charles W. Orr, left, trustees to the college's gym- \u25a0 speaker and chairman of the ject, with John Edwards of an- marshal at North Carolina Col- nasium. Among those shown State Board of Higher Educa- Durham as director, was lege's 56th annual commence- are, in foreground. Dr. Bascom tion, and William Jones, col- nounced here this week. ment Sunday, leads the pro- I Baynes, chairman of the board I! lege vice president. The NCVEP has received a one-ear operating grant from 13 Homes Of Burned Project Negroes the Voter Education of the Southern Regional Council. Higher Education Head Atlanta, Georgia, with which N. C. begin to its work. The NCVEP will be a state- In Haywood County, Tenn. wide organization with pre- Sees End Unequal Education cinct, county and congressional Says Gap of Negro district representation. It is similar to the South Carolina No Protection And White Colleges Voter Education Project, which Mrs. I. Stephens Owens to Get has operated successfully for Will Closed several years. Be non-partisan organiza- From Police The Watts Hill, Jr., chairman of tion will have three major mis- the North Carolina State Board Ph.D. -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE State Standards: There are many state Social Studies standards at every grade level from 4th through 12th that this unit addresses. It also incorporates many of the ELA Informational Text and Literary Text Standards. Below are just a few….. SS.4.C.2.2 Identify ways citizens work together to influence government and help solve community and state problems. SS.4.E.1.1 Identify entrepreneurs from various social and ethnic backgrounds who have influenced Florida and local economy. SS.5.C.2.4: Evaluate the importance of civic responsibilities in American democracy. SS.5.C.2.5: Identify ways good citizens go beyond basic civic and political responsibilities to improve government and society. SS.6.C.2.1: Identify principles (civic participation, role of government) from ancient Greek and Roman civilizations which are reflected in the American political process today, and discuss their effect on the American political process. SS.7.C: Civics and Government ( entire strand) SS.8.A.1.5: Identify, within both primary and secondary sources, the author, audience, format, and purpose of significant historical documents. SS.912.A.1: Use research and inquiry skills to analyze American history using primary and secondary resources. SS.912.A.1.3: Utilize timelines to identify time sequence of historical data. SS.912.C.2: Evaluate the roles, rights, and responsibilities of Unites States citizens and determine methods of active participation in society, government, and the political system. SS.912.C.2.10: Monitor current public issues in Florida. SS.912.C.2.11: Analyze public policy solutions or courses of action to resolve a local, state, or federal issue. -

The Student Voice, SNCC Newsletter, 1962-1963

- THE STUDE Vol. 3, No. NT 1 Issued by the Student VOI Nonviolent Coordinating CE Committee,197 1/2 Auburn Ave., Atlanta 3, Ga.April, 1962 TALLADEGA PROTESTS I Student Group Moves After Negotiations Fail TALLADEGA, ALA. - Be By Bob Zellner ginning with a march of 400 students and faculty mem TALLADEGA, ALABAMA - bers, Talladega Collegetook The stimulus for leadership a giant step toward freeing and effective social change their city of segregation. at Talladega College is found The march followed fruit in the Social Action Com less negotiation with Talla mittee (SAC) a group found dega Mayor J . L. Hardwick within the framework of the TALLADEGA STUDENTS PROTEST - Talladega College on April 5. The students ask college's Student Govern s tudents s taged a protest march against segregation on ed the Mayor to present plans ment. As the movement at April 6. Joined by some teachers from the school, the stu- 1 for integration of public faci Talladega has grown, the dents paraded around the Talladega Courthouse bearing lities in the city, and when concept that every student signs reading "We Want Open Libraries" - We Want Equal no plan was forthcoming, the at the college is a member Opportunity." Social Action Committee Chairman Dorothy group marched in protest. of SAC has grown also, and Vails is on the right, above, being inte rviewed by a re- The march was peaceful, and the original smaller com porter. Photo by Zellner. Mayor Hardwick praised the mittee is thought of a plan students and the Talledega ning group. SNCC Con-ference Slated I community for their c alm- Dorothy Vails, a native of J ness. -

Persecution and Perseverance: Black-White Interracial Relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina

PERSECUTION AND PERSEVERANCE: BLACK-WHITE INTERRACIAL RELATIONSHIPS IN PIEDMONT, NORTH CAROLINA by Casey Moore A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2017 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Aaron Shapiro ______________________________ Dr. David Goldfield ______________________________ Dr. Cheryl Hicks ii ©2017 Casey Moore ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSRACT CASEY MOORE. Persecution and perseverance: Black-White interracial relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina. (Under the direction of DR. AARON SHAPIRO) Although black-white interracial marriage has been legal across the United States since 1967, its rate of growth has historically been slow, accounting for less than eight percent of all interracial marriages in the country by 2010. This slow rate of growth lies in contrast to a large amount of national poll data depicting the liberalization of racial attitudes over the course of the twentieth-century. While black-white interracial marriage has been legal for almost fifty years, whites continue to choose their own race or other races and ethnicities, over black Americans. In the North Carolina Piedmont, this phenomenon can be traced to a lingering belief in the taboo against interracial sex politically propagated in the 1890s. This thesis argues that the taboo surrounding interracial sex between black men and white women was originally a political ploy used after Reconstruction to unite white male voters. In the 1890s, Democrats used the threat of interracial sex to vilify black males as sexual deviants who desired equality and voting rights only to become closer to white females. -

<Billno> <Sponsor>

<BillNo> <Sponsor> HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 8020 of the Second Extraordinary Session By Clemmons A RESOLUTION to honor the memory of United States Congressman John Robert Lewis. WHEREAS, the members of this General Assembly were greatly saddened to learn of the passing of United States Congressman John Robert Lewis; and WHEREAS, Congressman John Lewis dedicated his life to protecting human rights, securing civil liberties, and building what he called "The Beloved Community" in America; and WHEREAS, referred to as "one of the most courageous persons the Civil Rights Movement ever produced," Congressman Lewis evidenced dedication and commitment to the highest ethical standards and moral principles and earned the respect of his colleagues on both sides of the aisle in the United States Congress; and WHEREAS, John Lewis, the son of sharecropper parents Eddie and Willie Mae Carter Lewis, was born on February 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama, and was raised on his family's farm with nine siblings; and WHEREAS, he attended segregated public schools in Pike County, Alabama, and, in 1957, became the first member of his family to complete high school; he was vexed by the unfairness of racial segregation and disappointed that the Supreme Court's 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education did not affect his and his classmates' experience in public school; and WHEREAS, Congressman Lewis was inspired to work toward the change he wanted to see by Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s sermons and the outcome of the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 and -

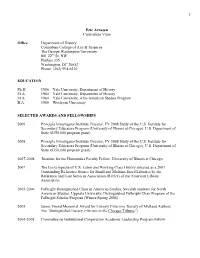

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

Attorney Dan R. Warren

Speech at the 43rd. Anniversary of the Signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 held in St. Augustine, July 2, 2007. By Dan R. Warren Forty- three years ago on June 19th, 1964, J. B. Stoner, a super racist and a member of the nation’s oldest terrorist organization, the Klan, stood across the street in the park where slaves were formally sold, and told an eager audience of hate filled men, women and children, that “the way to white supremacy is to rid congress of all those who voted for the civil rights act and get that ‘nigger’ loving Lyndon Johnson out of Washington.” A year earlier, Martin Luther King, stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D. C., and made his famous “I Have A Dream” speech. He told the thousands, who were gathered on the mall in the nations capital demanding freedom, that he had come to Washington to ask the nation to redeem a promise made by the founding fathers in 1776 when they proclaimed to the world that in this new nation “all men are created equal.” “In a sense”, Dr. King said, “We have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check” on that promise. “I want young men and young women, who are not alive today but who will come into this world, with new privileges and new opportunities to know and see that these new privileges and opportunities did not come without somebody suffering and somebody sacrificing for them.” It is hard to believe that only 44 years ago, 300 feet from the spot where I stand today, that a men, such as J. -

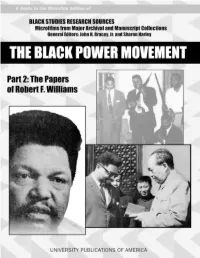

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams.