Attorney Dan R. Warren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE State Standards: There are many state Social Studies standards at every grade level from 4th through 12th that this unit addresses. It also incorporates many of the ELA Informational Text and Literary Text Standards. Below are just a few….. SS.4.C.2.2 Identify ways citizens work together to influence government and help solve community and state problems. SS.4.E.1.1 Identify entrepreneurs from various social and ethnic backgrounds who have influenced Florida and local economy. SS.5.C.2.4: Evaluate the importance of civic responsibilities in American democracy. SS.5.C.2.5: Identify ways good citizens go beyond basic civic and political responsibilities to improve government and society. SS.6.C.2.1: Identify principles (civic participation, role of government) from ancient Greek and Roman civilizations which are reflected in the American political process today, and discuss their effect on the American political process. SS.7.C: Civics and Government ( entire strand) SS.8.A.1.5: Identify, within both primary and secondary sources, the author, audience, format, and purpose of significant historical documents. SS.912.A.1: Use research and inquiry skills to analyze American history using primary and secondary resources. SS.912.A.1.3: Utilize timelines to identify time sequence of historical data. SS.912.C.2: Evaluate the roles, rights, and responsibilities of Unites States citizens and determine methods of active participation in society, government, and the political system. SS.912.C.2.10: Monitor current public issues in Florida. SS.912.C.2.11: Analyze public policy solutions or courses of action to resolve a local, state, or federal issue. -

Present Perfect Progressive Tense Mike Taylor

PRESENT PERFECT PROGRESSIVE TENSE MIKE TAYLOR Publication Date: 2019 Medium: silkscreen Binding: hand sewn Dimensions: Pages: 16 Edition Size: 11 Origin Description: Through extensive research at the ACCORD Civil Rights Museum in St. Augustine Florida, where the artist now resides, Taylor constructs a narrative of events between 1960 and 1964 chronicling the Civil Rights struggles of St. Augustine’s residents and the city’s resistance to racial integration. The artist reanimates these occurrences through a combination of forthright text and brash imagery. Taylor’s iconic illustrative style comprises complex and layered brushwork. The contrasting colors and overlapping imagery of the multilayered screen prints add to the chaos of the events and the struggles faced by the Civil Rights movement in St. Augustine and throughout the country. As the title implies, elements from this historical narrative continue to seep into the present day, may this edition be used as a teaching tool to guide educators, activists and advocates. From the artist: In the grammatical sense, the Present Perfect Progressive Tense refers to an action that has begun in the past, continues into the present, and possibly into the future. As such, the events of the Civil Rights Movement in St. Augustine, Florida are as much a part of the city today as they were in 1964. Trading solely on its identity as the oldest European settlement in the U.S., the town was readying itself to celebrate its 400th anniversary in 1965. Local activists from the NAACP contacted president Kennedy to ask he withhold considerable federal funding for what was to be a segregated celebration. -

The Foundations of Civil Rights Movement

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2014 Before King Came: The oundF ations of Civil Rights Movement Resistance and St. Augustine, Florida, 1900-1960 James G. Smith University of North Florida Suggested Citation Smith, James G., "Before King Came: The oundF ations of Civil Rights Movement Resistance and St. Augustine, Florida, 1900-1960" (2014). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 504. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/504 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2014 All Rights Reserved BEFORE KING CAME: THE FOUNDATIONS OF CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT RESISTANCE AND SAINT AUGUSTINE, FLORIDA, 1900-1960 By James G. Smith A thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES April, 2014 Unpublished work © James Gregory Smith Certificate of Approval The Thesis of James G. Smith is approved: _______________________________________ Date: __________________ Dr. James J. Broomall _______________________________________ Date: __________________ Dr. David T. Courtwright _______________________________________ Date: __________________ Dr. Denise I. Bossy Accepted for the History Department: _______________________________________ Date: __________________ Dr. Charles E. Closmann Chair Accepted for the College of Arts and Sciences: _______________________________________ Date: __________________ Dr. Barbara A. Hetrick Dean Accepted for the University: _______________________________________ Date: __________________ Dr. Len Roberson Dean of the Graduate School ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. -

July 2009 Newsletter

th The 40 ACCORD, Inc. P.O. Box 697 St. Augustine, FL 32085 Newsletter Publisher: GPD Volume Number: 3 Issue Number: 4 Date: July, 2009 Freedom Trail Launched cont. Freedom Trail Launched By David Nolan Jackson was also beaten, with his colleagues, Dr. Robert Hayling, Clyde Jenkins, and James Hauser, at a Ku Klux Klan rally held in the fall of 1963 The 45th anniversary of the signing of the landmark Civil Rights Act of behind what is now the Big Lots shopping center. He later became one of the 1964 was celebrated here by the launching of the third phase of the first black repairmen hired by the telephone company, and worked at that job Freedom Trail of historic sites of the civil rights movement, sponsored by for 23 years before retirement. Jackson is quoted at length in Tom Dent's ACCORD with the support of the Northrop Grumman Corporation. 1997 book Southern Journey that deals with places that played a prominent role in the civil rights movement. A tour of the Freedom Trail on the Red Trains included a stop on Julia Street for the symbolic unveiling of a marker at the Habitat for Humanity Carolyn Fisher, with accompanist Philip Brown, moved the crowd with a home of Audrey Nell Edwards, one of the St. Augustine Four who spent stirring rendition of "May the Works I've Done Speak for Me," the song six months in jail and reform school in 1963 and 1964 for asking to be that was sung at the 2002 funeral of civil rights activist Katherine "Kat" served at the local Woolworth's lunch counter. -

Grassroots Impacts on the Civil Rights Movement

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship Summer 2018 Grassroots Impacts on the Civil Rights Movement: Christian Women Leaders’ Contributions to the Paradigm Shift in the Tactics of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Its Affiliates Wook Jong Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Wook Jong. (2018). Grassroots Impacts on the Civil Rights Movement: Christian Women Leaders’ Contributions to the Paradigm Shift in the Tactics of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Its Affiliates. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 149. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/149. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/149 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grassroots Impacts on the Civil Rights Movement: Christian Women Leaders’ Contributions to the Paradigm Shift in the Tactics of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Its Affiliates By Wook Jong Lee Claremont Graduate University 2018 © Copyright Wook Jong Lee, 2018 All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number:10844448 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10844448 Published by ProQuest LLC ( 2018). -

CENTERS of the SOUTHERN STRUGGLE FBI Files on Montgomery, Albany, St

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES: Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections August Meier and John H. Bracey, Jr. General Editors CENTERS OF THE SOUTHERN STRUGGLE FBI Files on Montgomery, Albany, St. Augustine, Selma, and Memphis > >* »^«•r UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES: Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections August Meier and John H. Bracey, Jr. General Editors CENTERS OF THE SOUTHERN STRUGGLE FBI Files on Montgomery, Albany, St. Augustine, Selma, and Memphis Edited by David J. Garrow Guide compiled by Michael Moscato and Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA 44 North Market Street • Frederick, MD 21701 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Centers of the southern struggle [microform]. (Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed reel guide, compiled by Michael Moscato and Martin P. Schipper. Includes index. 1. Afro-Americans-Civil rights-History--20th century-Sources. 2. Civil rights movements- United States-History-20th century-Sources. 3. Afro-Americans-H ¡story-1877-1964~Sources. 4. United States-Race relations-Sources. 5. United States. Federal Bureau of Investigation- Archives. 6. Afro-Americans-Civil rights-Southern States~History-20th century-Sources. 7. Southern States-Race relations-Sources. I. Garrow, David J., 1953- . II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. Moscato, Michael. IV. United States. Federal Bureau of Investigation. V. University Publications of America. VI. Series. [E185.61] 975,.00496073 88-37866 ISBN 1-55655-047-2 (microfilm) Copyright ©1988 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-047-2. -

St. Augustine National Register Historic District (2016)

ST. AUGUSTINE INVENTORY ST. JOHNS COUNTY, FLORIDA Prepared for The City of St. Augustine St. Augustine, Florida and Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources Tallahassee, Florida Prepared by Patricia Davenport, MHP Environmental Services, Inc. and Paul Weaver Historic Property Associates, Inc. 30 June 2016 Grant No. S1601 ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES, INC. 7220 Financial Way, Suite 100 Jacksonville, Florida 32256 (904) 470-2200 St. Augustine National Register Historic District Survey Report For the City of St. Augustine EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Environmental Services Inc. of Jacksonville, Florida with assistance from Historic Property Associates of St. Augustine, Florida, conducted an inventory of structures within the St. Augustine National Register Historic District, for the City of St. Augustine, St. John’s County, Florida from December 2015 through June 2016. The survey was conducted under contract number RFP #PB2016-01 with the City of St. Augustine to fulfill requirements under a Historic Preservation Small-Matching Grant (CSFA 45.031), grant number S1601. The objectives of the survey was to update the inventory of historic structures within the St. Augustine National Register Historic District, and to record and update Florida Master Site File (FMSF) forms for all structures 45 years old or older, and for any “reconstructions” on original locations utilizing the Historic Structure Form and assess their eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). All work was intended to comply with Section 106 of the National Historic preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966 (as amended) as implemented by 36 CFR 800 (Protection of Historic Properties), Chapter 267 F.S. and the minimum field methods, data analysis, and reporting standards embodied in the Florida Division of Historic Resources’ (FDHR) Historic Compliance Review Program (November 1990, final draft version). -

Remembering Dr. King: 1929 – 1968 Classroom Resources

Remembering Dr. King: 1929 – 1968 Classroom Resources The following materials are designed to help About the exhibiton: students analyze and interpret the photographs in The Chicago History Museum’s exhibiton the exhibiton. They can be used in the classroom as Remembering Dr. King: 1929-1968 invites well as during a visit to the exhibiton. visitors to walk through a winding gallery that features over 25 photographs depictng key moments in Dr. King’s work and the Civil Rights Included in this packet: movement, with a special focus on his tme in Recommended for grades 6 –12 Chicago. ñ Timeline of Dr. King’s life — contains the informaton from the exhibiton related to the life of Dr. King. Chicago, like other U.S. cites, erupted in the ñ Timeline of Natonal Civil Rights Events — contains the wake of King’s assassinaton on April 4, 1968. informaton from the exhibiton related to natonal events that While the center of his actvism was focused on took place during the Civil Rights Era. dismantling southern Jim Crow, the systems ñ Reading Photographs Worksheet — students “read” and that kept African Americans oppressed in the interpret the photograph and answer some questons. American South, he spent tme in Chicago and ñ Photograph Analysis Worksheet — students analyze, consider ofen spoke out on the realites of northern image context and identfy their questons about the discriminaton, partcularly around the issues of photograph. Please note, this worksheet ends with the same poverty, educaton and housing. wrap up questons as the frst. For more informaton on visitng the Chicago Please note: The photographs used for the actvites are available History Museum, visit htps:// in a second PDF. -

SCLC Scores Victory in St. Augustine Against Klan, Violence

SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE Special St. Augustine Issue m INSIDE THIS ISSUE ~~t ~~r r~~ Editorial __ ______________________ Page f~~ 4 ::":.: :~::i SDarahK~attown .Bt oyle _____pPage 5 ::::;: r. mg rI es __________ age 7 ::··1 5 :::1: I ~e~O~::wL;b:h;~; ::: ::: 8 ::;::: Letter From Jail _________ .Page 3 : ~:~:~ ~~f Volume" June, 1964 Number 7 ::::~ Why St. Augustine? _____ .Page 12 :::~; ======================================= :;:::; SCLC Scores Victory In St. Augustine Against Klan, Violence Rebuilt Georgia Churches Dedicated Demonstrators Assaulted The three Negro churches which were burned two years ago in the rural area of southwest Georgia, were rededicated on Sunday, June 28, by SCLC President By Police, Ku Klux Klan Martin Luther King, Je. and others who had spearheaded a fund-raising drive to get them rebuilt. After more than a month of raging Addressing more than 600 persons at Mt. Olive Baptist Church, Dr. King violence in St Augustine, Florida, declared: "Two years ago I stood among the smoldering ruins of these churches. America's oldest city, in which more Those days told us of man's potential for than 300 SCLC-Ied demonstrators were eviL Now we see the goodness of man re arrested and scores of others injured flected. These new churches symbolize the by Klansmen wielding tire chains, and quest for human dignity. You can't kill an Report 275,000 Negroes other weapons, Dr. Martin Luther idea. It will live on. The rebuilding of these Registered In Georgia King, Jr. was able to proclaim victory churches symbolizes this fact." in this rock-bound bastion of segregation and Cost $100,000 An estimated 275,000 Negroes are discrimination. -

Local Protest and Federal Policy: the Impact of the Civil Rights Movement on the 1964 Civil Rights Act1

Sociological Forum, Vol. 30, No. S1, June 2015 DOI: 10.1111/socf.12175 © 2015 Eastern Sociological Society Local Protest and Federal Policy: The Impact of the Civil Rights Movement on the 1964 Civil Rights Act1 Kenneth T. Andrews2 and Sarah Gaby3 When and how do movements influence policy change? We examine the dynamics leading up to Kennedy’s decision to pursue major civil rights legislation in 1963. This marked a key turning point in shifting the exec- utive branch from a timid and gradualist approach. Although it is widely taken for granted that the civil rights movement propelled this shift, how the movement mattered is less clear. While most protest targeted local economic actors, movement influence was exerted at the national level on political actors. Thus, move- ment influence was indirect. We focus on the relationship between local movement efforts to desegregate pub- lic accommodations (restaurants, movie theaters, hotels, etc.) and federal responses to movement demands. Although exchanges between movement actors and the federal government took place throughout the period, the logic of federal response evolved as political actors sought strategies to minimize racial conflict. Specifically, the Kennedy administration shifted to a dual strategy. First, the Department of Justice attempted to promote “voluntary” desegregation by working with executives of national companies and civic groups. Second, administration officials worked with these same groups to build support for major legislation among key interest groups. This shift toward a more assertive and proactive intervention in civil rights stands in contrast to the pessimism regarding the prospects for federal policy only a few months earlier. -

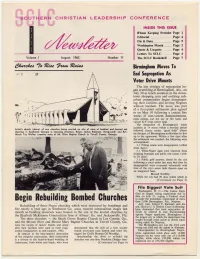

Begin Rebqilding Bombed Churches to Order the Immediate Registration of More Than 2,000 Birmingham, Ala., Negroes

OUTHER CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE Volume 1 August, 1963 Number 11 Birmingham Moves To End Segregation As Voter Drive Mounts The last vestiges of segregation be gan crumbling in Birmingham, Ala., on July 30 as lunch counters in the down town shopping area and outlying sub urban communities began desegregat ing their facilities and serving Negroes without incident. The move was part of a four-point settlement plan agreed to on May 10 following a crucial five weeks of non-violent demonstrations, mass jailings and the use of fire hoses and vicious K-9 corps police dogs. The integration of Birmingham's lunch counters in 14 stores within a two-day period Artist's sketch (above) of new churches being erected on site of ruins of bombed and burned out churches in Southwest Georgia is imposing structure. Below, Jackie Robinson (foreground) and Rev. followed closely earlier "good faith" efforts Wyatt Tee Walker examine ruins of Mt. Olive Baptist Church in Terrell County, Georgia. on the part of Birmingham authorities to live up to the agreement. Within a few days after . •, ;. :::~ /' the settlement was reached, the following were accomplished: 1.) Fitting rooms were desegregated (within three days). 2.) White-Negro signs were removed from drinking fountains and public rest rooms (with in 30 days) . 3.) Public golf courses, closed by the city following a court order last year that they be desegregated, were re-opened voluntarily with four of the city's seven links thrown open on an integrated basis. Moved Swiftly While the city had 90 days within which to (Continued on Page 3) File Biggest Vote Suit Washington, D. -

Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970 Part 4: Records of the Program Department Editorial Adviser Cynthia P. Lewis Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Blair Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970 [microform] / project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. microfilm reels. — (Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Blair D. Hydrick, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970. Contents: pt. 1. Records of the President’s Office—[Etc.]— pt. 4. Records of the Program Department ISBN 1-55655-558-X (pt. 4 : microfilm) 1. Southern Christian Leadership Conference—Archives. 2. Afro- Americans—Civil rights—Southern States—History—Sources. 3. Civil rights movements—United States—History—20th century— Sources. 4. Southern States—Race relations—History—Sources. I. Boehm, Randolph. II. Hydrick, Blair. III. Southern Christian Leadership Conference. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970. VI. Series. [E185.61] 323.1’196073075—dc20 95-24346 CIP Copyright © 1995 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-558-X. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................... vii Scope and Content Note.....................................................................................