War Against the Panthers: a Study of Repression in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F.B.I. Agent Testifies Panther Told of Shoothig Murder Victim

"George said that if anyone THE NEW YORK TIMES, I didn't_ like what he did they would get the same treatment," the agentlestitied.. qUoting the a F.B.I. Agent Testifies Panther defendant. d In cross-examination, Mr. S Told of Shoothig Murder Victim Metucas's lawyer, Theodore I. Koskoff, asked Mr. Twede o: whether he had ever made a By JOSEPH LELYVELD report that Mr. McLucas had w special to The Why Yon Tht4tO r said that he. obeyed the order in NEW HAVEN, July 21 ---, to make sure Rackley was dead til Wain% McLucas admitted last' Fears for Life Cited because he feared "that if he th ct yestr 'that he had fired a shot In fact, the F. B. I. agent, failed to do as ordered he into the body of Alex Rackley would be shot by George Order to make sure that he Lynn G. Twedsi of Salt Lake Sams." M was dead, an agent of the Fed- City, testified that Mr. McLucas The agent hesitated and the eral Bureau of Investigation had indicated he had "become question had to be read back to testified here today. disenchanted with the party be- to him twice before he an- m, McLucas, the first of cause of the violence" and swered directly, "yes." Fi eigh( Black Panthers to stand of wanted to quit. But he was Mr. Koskoff used the cross- trial here in connection with examination to stres small acts fo the Rackley slaying, was said afraid to do so because "Ife had of mercy Mr. -

The History of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a Curriculum Tool for Afrikan American Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies. Kit Kim Holder University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Holder, Kit Kim, "The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4663. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4663 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES A Dissertation Presented By KIT KIM HOLDER Submitted to the Graduate School of the■ University of Massachusetts in partial fulfills of the requirements for the degree of doctor of education May 1990 School of Education Copyright by Kit Kim Holder, 1990 All Rights Reserved THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966 - 1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES Dissertation Presented by KIT KIM HOLDER Approved as to Style and Content by ABSTRACT THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1971 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 1990 KIT KIM HOLDER, B.A. HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE M.S. BANK STREET SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Directed by: Professor Meyer Weinberg The Black Panther Party existed for a very short period of time, but within this period it became a central force in the Afrikan American human rights/civil rights movements. -

Race, Governmentality, and the De-Colonial Politics of the Original Rainbow Coalition of Chicago

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2012-01-01 In The pirS it Of Liberation: Race, Governmentality, And The e-CD olonial Politics Of The Original Rainbow Coalition Of Chicago Antonio R. Lopez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Lopez, Antonio R., "In The pS irit Of Liberation: Race, Governmentality, And The e-CD olonial Politics Of The Original Rainbow Coalition Of Chicago" (2012). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2127. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2127 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE SPIRIT OF LIBERATION: RACE, GOVERNMENTALITY, AND THE DE-COLONIAL POLITICS OF THE ORIGINAL RAINBOW COALITION OF CHICAGO ANTONIO R. LOPEZ Department of History APPROVED: Yolanda Chávez-Leyva, Ph.D., Chair Ernesto Chávez, Ph.D. Maceo Dailey, Ph.D. John Márquez, Ph.D. Benjamin C. Flores, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Antonio R. López 2012 IN THE SPIRIT OF LIBERATION: RACE, GOVERMENTALITY, AND THE DE-COLONIAL POLITICS OF THE ORIGINAL RAINBOW COALITION OF CHICAGO by ANTONIO R. LOPEZ, B.A., M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO August 2012 Acknowledgements As with all accomplishments that require great expenditures of time, labor, and resources, the completion of this dissertation was assisted by many individuals and institutions. -

50Th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr

50th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr. Jakobi Williams: library resources to accompany programs FROM THE BULLET TO THE BALLOT: THE ILLINOIS CHAPTER OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AND RACIAL COALITION POLITICS IN CHICAGO. IN CHICAGO by Jakobi Williams: print and e-book copies are on order for ISU from review in Choice: Chicago has long been the proving ground for ethnic and racial political coalition building. In the 1910s-20s, the city experienced substantial black immigration but became in the process the most residentially segregated of all major US cities. During the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, long-simmering frustration and anger led many lower-class blacks to the culturally attractive, militant Black Panther Party. Thus, long before Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition, made famous in the 1980s, or Barack Obama's historic presidential campaigns more recently, the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party (ILPBB) laid much of the groundwork for nontraditional grassroots political activism. The principal architect was a charismatic, marginally educated 20-year-old named Fred Hampton, tragically and brutally murdered by the Chicago police in December 1969 as part of an FBI- backed counter-intelligence program against what it considered subversive political groups. Among other things, Williams (Kentucky) "demonstrates how the ILPBB's community organizing methods and revolutionary self-defense ideology significantly influenced Chicago's machine politics, grassroots organizing, racial coalitions, and political behavior." Williams incorporates previously sealed secret Chicago police files and numerous oral histories. Other review excerpts [Amazon]: A fascinating work that everyone interested in the Black Panther party or racism in Chicago should read.-- Journal of American History A vital historical intervention in African American history, urban and local histories, and Black Power studies. -

The Lonnie Mclucas Trial and Visitors from Across the Eastern Seaboard Gathered to Protest the Treatment of Black Panthers in America

: The Black Panthers in Court On May I, 19 70, a massive demonstration was held on The Black Panthers in Court: 5 the New Haven Green. University students, townspeople The Lonnie McLucas Trial and visitors from across the Eastern Seaboard gathered to protest the treatment of Black Panthers in America. Just on the northern edge of the Green sat the Superior Court building where Bobby Seale and seven other Pan thers were to be tried for the murder of Alex Rackley. In order to sift out the various issues raised by the prose cutions and the demonstration, and to explore how members of the Yale community ought to relate to these trials on its doorstep, several students organized teach ins during the week prior to the demonstration. Among those faculty members and students who agreed to parti cipate on such short notice were Professors Thomas 1. Emerson and Charles A. Reich of the Yale Law School and J. Otis Cochran, a third-year law student and presi dent of the Black American Law Students Association. They have been kind enough to allow Law and Social Action to share with our readers the thoughts on the meaning and impact of political trials which they shared with the Yale community at that time. Inspired by the teach-ins and, in particular, by Mr. Emerson's remarks, Law and Social Action decided to interview people who played leading roles in the drama that unfulded around the Lonnie McLucas trial. We spoke with Lonnie McLucas, several jurors, defense at torneys, some of the organizers of the demonstrations that took place on May Day and throughout the sum mer, and several reporters who covered the trial. -

Karenga's Men There, in Campbell Hall. This Was Intended to Stop the Work and Programs of the Black

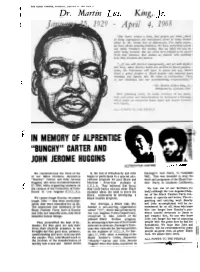

THE BLACK P'"THRR. """0". J'"""V "' ,~, P'CF . ,J: Dr. Martin - II But there comes a time, that. peoPle get tired...tired of being segregated and humiliated; tired of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression. For many years, we have shown amazing patience. We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice. "...If you will protest courageously, and yet with dignity and love, when history books are written in future genera- tions, the historians will have to pause and say, 'there lived a great peoPle--a Black peoPle--who injected new meanir:&g and dignity into the veins of civilization.' This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility." t.1 " --Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Montgomery, Alabama 1956 With pulsating voice, he made mockery of our fears; with convictlon and determinatlon he delivered a Message which made us overcome these fears and march forward with dignity . ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE \'-'I'; ~ f~~ ALPRENTICE CARTER JOHN HUGGINS We commemorate the lives of two In the fall of 1968,Bunchy and John Karenga's men there, in Campbell of our fallen brothers, Alprentice began to participate in a special edu- Hall. This was intended to stop the "Bunchy" Carter and John Jerome cational program for poor Black and work and programs of the Black Pan- Huggins, who were murdered J anuary Mexican -American students at ther Party in Southern California. -

On the Black Panther Party

STERILIZATION-ANOTHER PARTOF THE PLAN OFBLACK GENOCIDE 10\~w- -~ ., ' ' . - _t;_--\ ~s,_~=r t . 0 . H·o~u~e. °SHI ~ TI-lE BLACK PANTI-lER, SATURDAY, MAY 8, 1971 PAGE 2 STERILIZATION-ANOTHER PART OF THE PLAN OF f;Jti~~~ oF-~dnl&r ., America's poor and minority peo- In 1964, in Mississippi a law was that u ••• • Even my maid said this should ple are the current subject for dis- passed that actually made it felony for be done. She's behind it lO0 percent." cussion in almost every state legis- anyone to become the parent of more When he (Bates) argued that one pur latur e in the country: Reagan in Cali- than one "illegitimate" child. Original- pose of the bill was to save the State fornia is reducing the alr eady subsis- ly, the bill carried a penalty stipu- money, it was pointed out that welfare tance aid given to families with children; lation that first offenders would be mothers in Tennessee are given a max O'Callaghan in Nevada has already com- sentenced to one to three years in the imum of $l5.00 a month for every child pletely cut off 3,000 poor families with State Penitentiary. Three to five years at home (Themaxim!,(,mwelfarepayment children. would be the sentence for subsequent in Tennesse, which is for a family of However, Tennessee is considering convictions. As an alternative to jail- five or more children, is $l6l.00 per dealing with "the problem" of families in~, women would have had the option of month.), and a minimum of $65.00 with "dependant children" by reducing being sterilized. -

A Nation of Law? (1968-1971) BOBBY SEALE

A Nation of Law? (1968-1971) BOBBY SEALE: When our brother, Martin King, exhausted a means of nonviolence with his life being taken by some racist, what is being done to us is what we hate, and what happened to Martin Luther King is what we hate. You're darn right, we respect nonviolence. But to sit and watch ourselves be slaughtered like our brother, we must defend ourselves, as Malcolm X says, by any means necessary. WILLIAM O'NEAL: At this point, I question the whole purpose of the Black Panther Party. In my thinking, they were necessary as a shock treatment for white America to see black men running around with guns just like black men saw the white man running around with guns. Yeah, that was a shock treatment. It was good in that extent. But it got a lot of black people hurt. ELAINE BROWN: There was no joke about what was going on, but we believed in our hearts that we should defend ourselves. And there were so many that did do that. NARRATOR: By 1968, the Black Panther Party was part of an increasingly volatile political scene. That summer, the National Democratic Convention in Chicago was disrupted by violent clashes between demonstrators and police. The war in Vietnam polarized the nation and the political and racial upheaval at home soon became an issue in the presidential campaign. PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: This is a nation of laws and as Abraham Lincoln had said, no one is above the law, no one is below the law, and we're going to enforce the law and Americans should remember that if we're going to have law and order. -

H I S T O R Y I S a W E a P O N ! BLACK AUGUST RESISTANCE August, One of the Hottest Months of the Year, Is Upo'n Us Again

HISTORY IS A WEAPON! BLACK AUGUST RESISTANCE August, one of the hottest months of the year, is upo'n us again. For many of us in the "New Afrikan Independence Movement", August is a month of both great historical and spiritual significance. It is one of the hottest months in many ways, many of the great Afrrkan slave rebellions, including Gabriel Prosser's and Nat Turner's were planned for August. It is the month of the birth of the great Pan-Afri- kanist and Black Nationalist leaders, Marcus Garvey and also of our New Afrikan Freedom Fighter, Dr. Mutulu Shakur. New Afrikans took to the streets in rebellions in Watts, California in August 1965. On August 18,1971 in Jackson Mississippi, the offical residence of the Republic Of New Afrika was raided by Mississippi police and F.B.I, agents, gunfire was exchanged and when the smoke had cleared, one policeman laid dead and two other agents were wounded. For success- fully defending themselve's, these brothers and sisters were charged with "waging war against the state of Mississippi", they became known as the RNA-J5/. August 1994. marks the 15th anniversary of Black August commemorations, the promotion of a couscious, "non-sectarian mass based". Mew Afrikan Resistance Culture, both inside and outside the prison walls all across the U.S. Empire. Black August originally started among the brothers in the California penal system to honor three fallen comrades and to promote culture resistance and revolutionary developement. The first brother, Jonathan Jackson, a 17 year old manchild was gunned down August 7,1970 outside a Marin County California courthouse in an armed attempt to liberate three imprisoned Black Liberation Fighters (James Me Clain, William Christmans, and Ruchell Magee). -

New Haven Black Panther Trials and May Day at Yale

New Haven Black Panther Trials and May Day at Yale May 19, 1969, Bobby Seale, national chairman of the Black Panther Party, comes to New Haven to deliver a speech at Yale. May 20, 1969, 19-year-old Black Panther Alex Rackley is murdered in New Haven, CT. According to Murder in the Model City, Rackley had been suspected of beinG a police informant and had been executed by local Panther party members. Tapes and testimony now reveal that GeorGe Sams, Lonnie McLucas and Warren Kimbro were Rackley’s actual executioners. May 22, 1969, Police raid the New Haven Black Panther headquarters (365 Orchard street) and arrest a number of local panthers, includinG Ericka HuGGins, an important leader of the local Panther party. August, 1969, Panther GeorGe Sams swore out an affidavit implicatinG Chairman Bobby Seale in Rackley’s murder. His testimony has since been proven to be false. March, 1970, Chairman Bobby Seale is extradited to Connecticut, and New Haven becomes the center of Panther and Yippie protest efforts aGainst his trial. The trials for Bobby Seale and the other Panther defendants is set for the summer of 1970. Early April, 1970, the Panthers and other radical reform movements decide to hold a national rally in New Haven on May 1, 1970. April 15, 1970, Harvard closes and locks its Gates against a rally orGanized by the white radical Group Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Violence ensues between the 3,000 protestors and the 2,000 police officers summoned to protect the Harvard campus. By the end of the niGht, 214 people are hospitalized. -

History of Gangs in the United States

1 ❖ History of Gangs in the United States Introduction A widely respected chronicler of British crime, Luke Pike (1873), reported the first active gangs in Western civilization. While Pike documented the existence of gangs of highway robbers in England during the 17th century, it does not appear that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious street gangs. Later in the 1600s, London was “terrorized by a series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys [and they] fought pitched battles among themselves dressed with colored ribbons to distinguish the different factions” (Pearson, 1983, p. 188). According to Sante (1991), the history of street gangs in the United States began with their emer- gence on the East Coast around 1783, as the American Revolution ended. These gangs emerged in rapidly growing eastern U.S. cities, out of the conditions created in large part by multiple waves of large-scale immigration and urban overcrowding. This chapter examines the emergence of gang activity in four major U.S. regions, as classified by the U.S. Census Bureau: the Northeast, Midwest, West, and South. The purpose of this regional focus is to develop a better understanding of the origins of gang activity and to examine regional migration and cultural influences on gangs themselves. Unlike the South, in the Northeast, Midwest, and West regions, major phases characterize gang emergence. Table 1.1 displays these phases. 1 2 ❖ GANGS IN AMERICA’S COMMUNITIES Table 1.1 Key Timelines in U.S. Street Gang History Northeast Region (mainly New York City) First period: 1783–1850s · The first ganglike groups emerged immediately after the American Revolution ended, in 1783, among the White European immigrants (mainly English, Germans, and Irish). -

Ahmad A. Rahman's Making of Black

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Afro-American Studies Faculty Publication Series Afro-American Studies 2015 Ahmad A. Rahman’s Making of Black ‘Solutionaries’ Amilcar Shabazz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/afroam_faculty_pubs Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Amilcar, "Ahmad A. Rahman’s Making of Black ‘Solutionaries’" (2015). The Journal of Pan African Studies. 102. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/afroam_faculty_pubs/102 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Afro-American Studies Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ahmad A. Rahman’s Making of Black ‘Solutionaries’ by Amilcar Shabazz [email protected] Vice President, The National Council for Black Studies "Africa needs a new type of man. A dedicated, modest, honest and devoted man. A man who submerges self in the service of his nation and mankind. A man who abhors greed and deters vanity. A new type of man whose meekness is his strength and whose integrity is his greatness." –Osageyefo Kwame Nkrumah iii The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.8, no.9, December 2015 A few days before his death, the social media site (facebook) of Brother Ahmad Abdur Rahman (1951–September 21, 2015) featured the above quote along with a picture of Kwame Nkrumah. What is expressed, the call for a new kind of man, aptly serves as an epigraph to the story of Rahman’s own life.