Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

Everyday Life of Jews in Mariampole, Lithuania (1894–1911)1

Chapter 1 Everyday Life of Jews in Mariampole, Lithuania 1 (1894–1911) INTRODUCTION The urge to discover one‘s roots is universal. This desire inspired me to reconstruct stories about my ancestors in Mariampole, Lithuania, for my grandchildren and generations to come. These stories tell the daily lives and culture of Jewish families who lived in northeastern Europe within Russian-dominated Lithuania at the turn of the twentieth century. The town name has been spelled in various ways. In YIVO, the formal Yiddish transliteration, the town name would be ―Maryampol.‖ In Lithuanian, the name is Marijampolė (with a dot over the ―e‖). In Polish, the name is written as Marjampol, and in Yiddish with Hebrew characters, the name is written from and pronounced ―Mariampol.‖ In English spelling, the town name ‖מאַריאַמפּאָל― right to left as is ―Marijampol.‖ From 1956 until the end of Soviet control in 1989, the town was called ―Kapsukas,‖ after one of the founders of the Lithuanian Communist party. The former name, Mariampole, was restored shortly before Lithuania regained independence.2 For consistency, I refer to the town in the English-friendly Yiddish, ―Mariampole.‖3 My paternal grandparents, Dvore Shilobolsky/Jacobson4 and Moyshe Zundel Trivasch, moved there around 1886 shortly after their marriage. They had previously lived in Przerośl, a town about 35 miles southwest of Mariampole. Both Przerośl and Mariampole were part of the Pale of Settlement, a place where the Russian empire forced its Jews to live 1791–1917. It is likely that Mariampole promised to offer Jews a better life than the crowded conditions of the section of the Pale where my grandparents had lived. -

Workers of the World: International Journal on Strikes and Social Conflicts, Vol

François Guinchard was born in 1986 and studied social sciences at the Université Paul Valéry (Montpellier, France) and at the Université de Franche-Comté (Besançon, France). His master's dissertation was published by the éditions du Temps perdu under the title L'Association internationale des travailleurs avant la guerre civile d'Espagne (1922-1936). Du syndicalisme révolutionnaire à l'anarcho-syndicalisme [The International Workers’ Association before the Spanish civil war (1922-1936). From revolutionary unionism to anarcho-syndicalism]. (Orthez, France, 2012). He is now preparing a doctoral thesis in contemporary history about the International Workers’ Association between 1945 and 1996, directed by Jean Vigreux, within the Centre George Chevrier of the Université de Bourgogne (Dijon, France). His main research theme is syndicalism but he also took part in a study day on the emigration from Haute-Saône department to Mexico in October 2012. Text originally published in Strikes and Social Conflicts International Association. (2014). Workers of the World: International Journal on Strikes and Social Conflicts, Vol. 1 No. 4. distributed by the ACAT: Asociación Continental Americana de los Trabajadores (American Continental Association of Workers) AIL: Associazione internazionale dei lavoratori (IWA) AIT: Association internationale des travailleurs, Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores (IWA) CFDT: Confédération française démocratique du travail (French Democratic Confederation of Labour) CGT: Confédération générale du travail, Confederación -

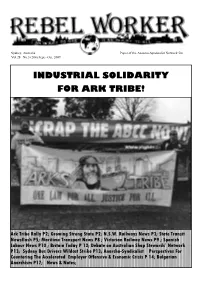

C:\Users\Mark\Documents\RWORKER\Rw Sept-Oct

Sydney, Australia Paper of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Network 50c Vol.28 No.3 (204) Sept.- Oct. 2009 INDUSTRIAL SOLIDARITY FOR ARK TRIBE! Ark Tribe Rally P2; Growing Strong State P2; N.S.W. Railways News P3; State Transit Newsflash P5; Maritime Transport News P8 ; Victorian Railway News P9 ; Spanish Labour News P10 ; Britain Today P 12; Debate on Australian Shop Stewards’ Network P13; Sydney Bus Drivers Wildcat Strike P13; Anarcho-Syndicalist Perspectives For Countering The Accelerated Employer Offensive & Economic Crisis P 14; Bulgarian Anarchism P17; News & Notes; 2 Rebel Worker suburbs in Adelaide. 200 people I think, destroying rights for the rest of us. The Rebel Worker is the bi-monthly maybe nearing 300? Judging by us having only time I felt like heckling was “like Paper of the A.S.N. for the propo- given out 50 leaflets to less than a quarter Ned Kelly, he’s been pushed around, gation of anarcho-syndicalism in of the crowd in about 2 minutes.5 political forced to do things he shouldn’t have to..” Australia. forces made an appearance, including the where I was too shy to heckle with “but he greens, democrats, an independent, ‘free still hasn’t shot any cops!” Unless otherwise stated, signed Australia party’(newly formed party of Would have got a laugh or two, especially Articles do not necessarily represent ‘motorcycle enthusiasts’(for anyone inter- from the “motorcycle enthusiasts”. Any- the position of the A.S.N. as a whole. nationally, bikers have been targeted by way.. to my understanding a motion was Any contributions, criticisms, letters absurd state powers recently, and have passed at the ACTU (Australian Council or formed a political party) and Socialist Al- of Trade Unions) (amazingly..) congress, Comments are welcome. -

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Warsaw 2013 Museum of the City of New York New York 2014 the Contemporary Jewish Muse

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Warsaw 2013 Museum of the City of New York New York 2014 The Contemporary Jewish Museum San Francisco 2015 Sokołów, video; 2 minutes Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York Letters to Afar is made possible with generous support from the following sponsors: POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Museum of the City of New York Kronhill Pletka Foundation New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Righteous Persons Foundation Seedlings Foundation Mr. Sigmund Rolat The Contemporary Jewish Museum Patron Sponsorship: Major Sponsorship: Anonymous Donor David Berg Foundation Gaia Fund Siesel Maibach Righteous Persons Foundation Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Anita and Ronald Wornick Major support for The Contemporary Jewish Museum’s exhibitions and Jewish Peoplehood Programs comes from the Koret Foundation. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw 05.18.2013 - 09.30.2013 Museum of the City of New York 10.22.2014 - 03.22.2015 The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco 02.26.2015 - 05.24.2015 Video installation by Péter Forgács with music by The Klezmatics, commissioned by the Museum of the History of Polish Jews and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. The footage used comes from the collections of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, the National Film Archive in Warsaw, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, Beit Hatfutsot in Tel Aviv and the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive in Jerusalem. 4 Péter Forgács / The Klezmatics Kolbuszowa, video; 23 minutes Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York 6 7 Péter Forgács / The Klezmatics beginning of the journey Andrzej Cudak The Museum of the History of Polish Jews invites you Acting Director on a journey to the Second Polish-Jewish Republic. -

“The Whole World Is Our Homeland”: Anarchist Antimilitarism

nº 24 - SEPTEMBER 2015 PACIFISTS DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR IN DEPTH “The whole world is our homeland”: Anarchist antimilitarism Dolors Marín Historian Anarchism as a form of human liberation and as a social, cultural and economic al- ternative is an idea born from the European Illustration. It belongs to the rationalism school of thought that believes in the education of the individual as the essential tool for the transformation of society. The anarchists fight for a future society in which there is no place for the State or authoritarianism, because it is a society structured in small, self-sufficient communities with a deep respect for nature, a concept already present among the utopian socialists. A communitarian (though non necessarily an- ti-individualistic) basis that will be strengthened by the revolutionary trade unionism who uses direct action and insurrectional tactics for its vindications. On a political level, the anarchists make no distinction between goals and methods, because they consider that the fight is in itself a goal. In the anarchist denunciation of the modern state’s authoritarianism the concepts of army and war are logically present. This denunciation was ever-present in the years when workers internationalism appeared, due to the growth of modern European na- tionalisms, the independence of former American colonies and the Asian and African context. The urban proletariat and many labourers from around the world become the cannon fodder in these bloodbaths of youth and devastations of large areas of the pla- net. The workers’ protest is hence channelled through its own growing organizations (trade unions, workmen’s clubs, benefit societies, etc), with the support and the louds- peaker of abundant pacifist literature that will soon be published in clandestine book- lets or pamphlets that circulate on a hand-to-hand basis (1). -

Bridging the “Great and Tragic Mekhitse”: Pre-War European

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

Rancour's Emphasis on the Obviously Dark Corners of Stalin's Mind

Rancour's emphasis on the obviously dark corners of Stalin's mind pre- cludes introduction of some other points to consider: that the vozlzd' was a skilled negotiator during the war, better informed than the keenly intelli- gent Churchill or Roosevelt; that he did sometimes tolerate contradiction and even direct criticism, as shown by Milovan Djilas and David Joravsky, for instance; and that he frequently took a moderate position in debates about key issues in the thirties. Rancour's account stops, save for a few ref- erences to the doctors' plot of 1953, at the end of the war, so that the enticing explanations offered by William McCagg and Werner Hahn of Stalin's conduct in the years remaining to him are not discussed. A more subtle problem is that the great stress on Stalin's personality adopted by so many authors, and taken so far here, can lead to a treatment of a huge country with a vast population merely as a conglomeration of objects to be acted upon. In reality, the influences and pressures on people were often diverse and contradictory, so that choices had to be made. These were simply not under Stalin's control at all times. One intriguing aspect of the book is the suggestion, never made explicit, that Stalin firmly believed in the existence of enemies around him. This is an essential part of the paranoid diagnosis, repeated and refined by Rancour. If Stalin believed in the guilt, in some sense, of Marshal Tukhachevskii et al. (though sometimes Rancour suggests the opposite), then a picture emerges not of a ruthless dictator coldly plotting the exter- mination of actual and potential opposition, but of a fear-ridden, tormented man lashing out in panic against a threat he believed to real and immediate. -

Noam Chomsky Articulates a Clear, Uncompromising Defense of the Libertarian Socialist (Anarchist) Vision

This classic talk delivered in 1970 has never seemed more current. In it Noam Chomsky articulates a clear, uncompromising defense of the libertarian socialist (anarchist) vision. NOAM CHOMSKY GOVERNMENT IN THE FUTURE ceros press department of republication on the high seas Government in the Future Talk given at the Poetry Center, New York City, Feb. 16, 1970 I think it is useful to set up as a framework for discussion four somewhat idealized positions with regard to the role of the state in an advanced industrial society. I want to call these positions: 1. Classical Liberal 2. Libertarian Socialist 3. State Socialist 4. State Capitalist and I want to consider each in turn. Also, I'd like to make clear my own point of view in advance, so that you can evaluate and judge what I am saying. I think that the libertarian socialist concepts, and by that I mean a range of thinking that extends from left-wing Marxism through to anarchism, I think that these are fundamentally correct and that they are the proper and natural extension of classical liberalism into the era of advanced industrial society. In contrast, it seems to me that the ideology of state socialism, i.e. what has become of Bolshevism, and that of state capitalism, the modern welfare state, these of course are dominant in the industrial societies, but I believe that they are regressive and highly inadequate social theories, and a large number of our really fundamental problems stem from a kind of incompatibility and inappropriateness of these social forms to a modern industrial society. -

Libertarian Socialism

Libertarian Socialism Politics in Black and Red Editors: Alex Prichard, Ruth Kinna, Saku Pinta, and David Berry The history of anarchist-Marxist relations is usually told as a history of faction- alism and division. These essays, based on original research and written espe- cially for this collection, reveal some of the enduring sores in the revolutionary socialist movement in order to explore the important, too often neglected left- libertarian currents that have thrived in revolutionary socialist movements. By turns, the collection interrogates the theoretical boundaries between Marxism and anarchism and the process of their formation, the overlaps and creative ten- sions that shaped left-libertarian theory and practice, and the stumbling blocks to movement cooperation. Bringing together specialists working from a range of political perspectives, the book charts a history of radical twentieth-century socialism, and opens new vistas for research in the twenty-first. Contributors examine the political and social thought of a number of leading socialists— Marx, Morris, Sorel, Gramsci, Guérin, C.L.R. James, Hardt and Negri—and key movements including the Situationist International, Socialisme ou Barbarie and Council Communism. Analysis of activism in the UK, Australasia, and the U.S. serves as the prism to discuss syndicalism, carnival anarchism, and the anarchistic currents in the U.S. civil rights movement. Contributors include Paul Blackledge, Lewis H. Mates, Renzo Llorente, Carl SUBJECT CATEGORY Levy, Christian Høgsbjerg, Andrew Cornell, Benoît Challand, Jean-Christophe Politics-Anarchism/Politics-Socialism Angaut, Toby Boraman, and David Bates. PRICE ABOUT THE EDITORS $26.95 Alex Prichard is senior lecturer in International Relations at the University of Exeter. -

Anarcha-Feminism.Pdf

mL?1 P 000 a 9 Hc k~ Q 0 \u .s - (Dm act @ 0" r. rr] 0 r 1'3 0 :' c3 cr c+e*10 $ 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.... 1 Anarcha-Feminism: what it is and why it's important.... 4 Anarchism. Feminism. and the Affinity Group.... 10 Anarcha-Feminist Practices and Organizing .... 16 Global Women's Movements Through an anarchist Lens ..22 A Brief History of Anarchist Feminism.... 23 Voltairine de Cleyre - An Overview .... 26 Emma Goldman and the benefits of fulfillment.... 29 Anarcha-Feminist Resources.... 33 Conclusion .... 38 INTRODUCTION This zine was compiled at the completion of a quarters worth of course work by three students looking to further their understanding of anarchism, feminism, and social justice. It is meant to disseminate what we have deemed important information throughout our studies. This information may be used as a tool for all people, women in particular, who wish to dismantle the oppressions they face externally, and within their own lives. We are two men and one woman attempting to grasp at how we can deconstruct the patriarchal foundations upon which we perceive an unjust society has been built. We hope that at least some component of this work will be found useful to a variety of readers. This Zine is meant to be an introduction into anarcha-feminism, its origins, applications, and potentials. Buen provecho! We acknowledge that anarcha-feminism has historically been a western theory; thus, unfortunately, much of this ziners content reflects this limitation. However, we have included some information and analysis on worldwide anarcha-feminists as well as global women's struggles which don't necessarily identify as anarchist. -

Finnish Studies Volume 18 Number 2 July 2015 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-937875-95-4

JOURNAL OF INNISH TUDIES F S International Influences in Finnish Working-Class Literature and Its Research Guest Editors Kirsti Salmi-Niklander and Kati Launis Theme Issue of the Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 18 Number 2 July 2015 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-937875-95-4 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University; hilary.virtanen@finlandia. edu Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Titus Hjelm, Lecturer, University College London Richard Impola, Professor Emeritus, New Paltz, New York Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of Finnish Literature, University of Helsinki Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, Institute for Northern Culture, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury George Schoolfield, Professor Emeritus, Yale University Beth L.