Bridging the “Great and Tragic Mekhitse”: Pre-War European

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everyday Life of Jews in Mariampole, Lithuania (1894–1911)1

Chapter 1 Everyday Life of Jews in Mariampole, Lithuania 1 (1894–1911) INTRODUCTION The urge to discover one‘s roots is universal. This desire inspired me to reconstruct stories about my ancestors in Mariampole, Lithuania, for my grandchildren and generations to come. These stories tell the daily lives and culture of Jewish families who lived in northeastern Europe within Russian-dominated Lithuania at the turn of the twentieth century. The town name has been spelled in various ways. In YIVO, the formal Yiddish transliteration, the town name would be ―Maryampol.‖ In Lithuanian, the name is Marijampolė (with a dot over the ―e‖). In Polish, the name is written as Marjampol, and in Yiddish with Hebrew characters, the name is written from and pronounced ―Mariampol.‖ In English spelling, the town name ‖מאַריאַמפּאָל― right to left as is ―Marijampol.‖ From 1956 until the end of Soviet control in 1989, the town was called ―Kapsukas,‖ after one of the founders of the Lithuanian Communist party. The former name, Mariampole, was restored shortly before Lithuania regained independence.2 For consistency, I refer to the town in the English-friendly Yiddish, ―Mariampole.‖3 My paternal grandparents, Dvore Shilobolsky/Jacobson4 and Moyshe Zundel Trivasch, moved there around 1886 shortly after their marriage. They had previously lived in Przerośl, a town about 35 miles southwest of Mariampole. Both Przerośl and Mariampole were part of the Pale of Settlement, a place where the Russian empire forced its Jews to live 1791–1917. It is likely that Mariampole promised to offer Jews a better life than the crowded conditions of the section of the Pale where my grandparents had lived. -

NEWSLETTER Winter 2021 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

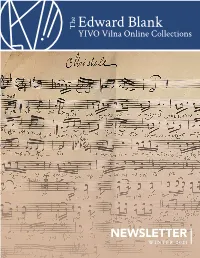

NEWSLETTER winter 2021 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, The Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections team has continued its exceptional work unabated throughout the past nine months of the COVID-19 pandemic under the superb leadership of Stefanie Halpern, Director of the YIVO Archives. The complex work of processing, conservation, and digitization has gone forward uninterrupted and with the enthusiasm and energy that bespeaks the tireless commitment of our YIVO staff. Their dedication is the mark of a vibrant institution, one of which I and the YIVO board are justly proud, as are many others in the global YIVO community. Our team’s collective efforts continually affirm the vitality of YIVO’s mission—preserving and disseminating the heritage of East European Jewish life. We honor their intensive work on the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections project much as we honor the sacrifices and dedication of those who came before us and who risked their lives to enable our access to these essential documents and artifacts. I hope you will join me in expressing your appreciation, including by making a gift in support of the Project. We welcome your participation and partnership in our restoration efforts. I also hope that you will explore our Archives and Library, our public and educational programs, our exhibitions, and social media offerings. In these and so many ways, you can help us to ensure that the spirit of YIVO remains a living reality for generations to come. Jonathan Brent Executive Director & CEO CONTACT For more information, please contact the YIVO Development Department: 212.294.6156 [email protected] DONATE ONLINE vilnacollections.yivo.org/Donate COVER: Handwritten music manuscript from a Yiddish operetta, ca. -

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Warsaw 2013 Museum of the City of New York New York 2014 the Contemporary Jewish Muse

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Warsaw 2013 Museum of the City of New York New York 2014 The Contemporary Jewish Museum San Francisco 2015 Sokołów, video; 2 minutes Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York Letters to Afar is made possible with generous support from the following sponsors: POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Museum of the City of New York Kronhill Pletka Foundation New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Righteous Persons Foundation Seedlings Foundation Mr. Sigmund Rolat The Contemporary Jewish Museum Patron Sponsorship: Major Sponsorship: Anonymous Donor David Berg Foundation Gaia Fund Siesel Maibach Righteous Persons Foundation Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Anita and Ronald Wornick Major support for The Contemporary Jewish Museum’s exhibitions and Jewish Peoplehood Programs comes from the Koret Foundation. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw 05.18.2013 - 09.30.2013 Museum of the City of New York 10.22.2014 - 03.22.2015 The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco 02.26.2015 - 05.24.2015 Video installation by Péter Forgács with music by The Klezmatics, commissioned by the Museum of the History of Polish Jews and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. The footage used comes from the collections of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, the National Film Archive in Warsaw, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, Beit Hatfutsot in Tel Aviv and the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive in Jerusalem. 4 Péter Forgács / The Klezmatics Kolbuszowa, video; 23 minutes Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York 6 7 Péter Forgács / The Klezmatics beginning of the journey Andrzej Cudak The Museum of the History of Polish Jews invites you Acting Director on a journey to the Second Polish-Jewish Republic. -

The Semitic Component in Yiddish and Its Ideological Role in Yiddish Philology

philological encounters � (�0�7) 368-387 brill.com/phen The Semitic Component in Yiddish and its Ideological Role in Yiddish Philology Tal Hever-Chybowski Paris Yiddish Center—Medem Library [email protected] Abstract The article discusses the ideological role played by the Semitic component in Yiddish in four major texts of Yiddish philology from the first half of the 20th century: Ysroel Haim Taviov’s “The Hebrew Elements of the Jargon” (1904); Ber Borochov’s “The Tasks of Yiddish Philology” (1913); Nokhem Shtif’s “The Social Differentiation of Yiddish: Hebrew Elements in the Language” (1929); and Max Weinreich’s “What Would Yiddish Have Been without Hebrew?” (1931). The article explores the ways in which these texts attribute various religious, national, psychological and class values to the Semitic com- ponent in Yiddish, while debating its ontological status and making prescriptive sug- gestions regarding its future. It argues that all four philologists set the Semitic component of Yiddish in service of their own ideological visions of Jewish linguistic, national and ethnic identity (Yiddishism, Hebraism, Soviet Socialism, etc.), thus blur- ring the boundaries between descriptive linguistics and ideologically engaged philology. Keywords Yiddish – loshn-koydesh – semitic philology – Hebraism – Yiddishism – dehebraization Yiddish, although written in the Hebrew alphabet, is predominantly Germanic in its linguistic structure and vocabulary.* It also possesses substantial Slavic * The comments of Yitskhok Niborski, Natalia Krynicka and of the anonymous reviewer have greatly improved this article, and I am deeply indebted to them for their help. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi �0.��63/�45�9�97-��Downloaded34003� from Brill.com09/23/2021 11:50:14AM via free access The Semitic Component In Yiddish 369 and Semitic elements, and shows some traces of the Romance languages. -

JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English

MONDAY The Rise of Yiddish Scholarship JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English As Jewish activists sought to build a modern, secular culture in the late nineteenth century they stressed the need to conduct research in and about Yiddish, the traditionally denigrated vernacular of European Jewry. By documenting and developing Yiddish and its culture, they hoped to win respect for the language and rights for its speakers as a national minority group. The Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut [Yiddish Scientific Institute], known by its acronym YIVO, was founded in 1925 as the first organization dedicated to Yiddish scholarship. Throughout its history, YIVO balanced its mission both to pursue academic research and to respond to the needs of the folk, the masses of ordinary Yiddish- speaking Jews. This talk will explore the origins of Yiddish scholarship and why YIVO’s work was seen as crucial to constructing a modern Jewish identity in the Diaspora. Cecile Kuznitz is Associate Professor of Jewish history and Director of Jewish Studies at Bard College. She received her Ph.D. in modern Jewish history from Stanford University and previously taught at Georgetown University. She has held fellowships at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. In summer 2013 she was a Visiting Scholar at Vilnius University. She is the author of several articles on the history of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Jewish community of Vilna, and the field of Yiddish Studies. English-Language Bibliography of Recent Works on Yiddish Studies CECILE KUZNITZ Baker, Zachary M. -

Th Trsformtion of Contmpora Orthodoxy

lïayr. Soloveitchik Haym Soloveitchik teaches Jewish history and thought in the Bernard Revel Graduate School and Stern College for Woman at Yeshiva University. RUP AN RECONSTRUCTION: TH TRSFORMTION OF CONTMPORA ORTHODOXY have occurred within my lifetime in the comniunity in which This essayI live. is The an orthodoxyattempt to in understand which I, and the other developments people my age,that were raised scarcely exists anymore. This change is often described as "the swing to the Right." In one sense, this is an accurate descrip- tion. Many practices, especially the new rigor in religious observance now current among the younger modern orthodox community, did indeed originate in what is called "the Right." Yet, in another sense, the description seems a misnomer. A generation ago, two things pri- marily separated modern Orthodoxy from, what was then called, "ultra-Orthodoxy" or "the Right." First, the attitude to Western culture, that is, secular education; second, the relation to political nationalism, i.e Zionism and the state of IsraeL. Little, however, has changed in these areas. Modern Orthodoxy stil attends college, albeit with somewhat less enthusiasm than before, and is more strongly Zionist than ever. The "ultra-orthodox," or what is now called the "haredi,"l camp is stil opposed to higher secular educa- tion, though the form that the opposition now takes has local nuance. In Israel, the opposition remains total; in America, the utili- ty, even the necessity of a college degree is conceded by most, and various arrangements are made to enable many haredi youths to obtain it. However, the value of a secular education, of Western cul- ture generally, is still denigrated. -

119 Kuznitz, Cecile Esther Readers of This Journal Are Undoubtedly Familiar

Book Reviews 119 Kuznitz, Cecile Esther YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture. Scholarship for the Yiddish Nation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014. 307 pp. ISBN 978-1-107-01420-6 Readers of this journal are undoubtedly familiar with the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, widely recognized today as the scholarly authority for the standardization of the Yiddish language. During its first, “European period” between the two world wars, YIVO was a global organization with headquar- ters in Vilna, Poland and branches elsewhere in “Yiddishland.” As war engulfed and ultimately consumed the eastern European heartland of Yiddish-speaking Jewry, its American division in New York City was transformed into its world center under the leadership of its guiding spirit Max Weinreich. Given the decisive role played by Weinreich, a path-breaking scholar of the Yiddish language and its cultural history, in shaping both the field of Yiddish Studies and YIVO, it is no surprise that the institute remains closely associated in the contemporary mind with his name and legacy. But YIVO (an acronym for Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut or Yiddish Scientific Institute, the name by which it was known in English into the 1950s as a statement of its commitment to Yiddish) was never the accomplishment of an individual or the expression of a single voice. Nor was academics in its most narrow sense nor the research and cultivation of the Yiddish language ever its exclusive focus. Rather, YIVO, as historian Cecile Kuznitz explains, was the creation of a cohort of scholars and cultural activists animated by a populist mission, many of whom knew each other since their days as politically engaged students at the University of St. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

Simon Goldberg

Simon Goldberg B.A., Yeshiva University, 2012 M.A., Haifa University, 2015 Shirley and Ralph Rose Fellow Simon Goldberg, recipient of the Hilda and Al Kirsch research award, examines documents fashioned in the Kovno (Kaunas) ghetto in Lithuania to explore the broader question of how wartime Jewish elites portrayed life in the ghetto. The texts that survived the war years in Kovno offer rich insights into ghetto life: they include an anonymous history written by Jewish policemen; a report written by members of the ghetto khevre kedishe (burial society); and a protocol book detailing the Ältestenrat’s wartime deliberations. Yet these documents primarily reflect the perspectives of a select few. Indeed, for decades, scholarship on the Holocaust in Kovno has been dominated by the writings of ghetto elites, relegating the testimonies of Jews who did not occupy positions of authority during the war to the margins. Goldberg’s dissertation explores how little-known accounts of the Kovno ghetto both challenge and broaden our understanding of wartime Jewish experience. At the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Goldberg examined records from the Central States Archives of Lithuania (LCVA). LCVA’s vast repository includes protocols, daily reports, arrest records, and meeting minutes that shed light on the institution of the Jewish police in the Kovno ghetto and the chronicle its members wrote in 1942 and 1943. The LCVA materials also include songs and poems that highlight social and cultural aspects of Jewish life across ghetto society. As the 2018-2019 Fellow in Baltic Jewish History at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, Goldberg studied the early historiography of the Kovno ghetto as reflected in the various newspapers and periodicals published in DP camps in Germany and Italy, including Unzer Weg and Ba’Derech. -

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Kelly. 2012. Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9830349 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Kelly Scott Johnson All rights reserved Professor Ruth R. Wisse Kelly Scott Johnson Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin Abstract The thesis represents the first complete academic biography of a Jewish clockmaker, warrior poet and Anarchist named Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard's experience was both typical and unique for a Jewish man of his era. It included four immigrations, two revolutions, numerous pogroms, a world war and, far less commonly, an assassination. The latter gained him fleeting international fame in 1926, when he killed the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura in Paris in retribution for pogroms perpetrated during the Russian Civil War (1917-20). After a contentious trial, a French jury was sufficiently convinced both of Schwarzbard's sincerity as an avenger, and of Petliura's responsibility for the actions of his armies, to acquit him on all counts. Mostly forgotten by the rest of the world, the assassin has remained a divisive figure in Jewish-Ukrainian relations, leading to distorted and reductive descriptions his life. -

View the Program & Bibliography

MONDAY Praxis Poems: JUL 01 Radical Genealogies of Yiddish Poetry ANNA ELENA TORRES | Delivered in English This talk will survey the radical traditions of Yiddish poetry, focusing on anarchist poetics and the press. Beginning with the Labor poets, also known as the Svetshop or Proletarian poets, the lecture discusses the formative role of the anarchist press in the development of immigrant social worlds. Between 1890 and World War I, Yiddish anarchists published more than twenty newspapers in the U.S.; these papers generally grew out of mutual aid societies that aspired to cultivate new forms of social life. Fraye Arbeter Shtime (Free Voice of Labor)—which was founded in 1890 and ran until 1977, making it the longest-running anarchist newspaper in any language—launched the careers of many prominent poets, including Dovid Edelshtat, Mani Leyb, Anna Margolin, Fradl Shtok, and Yankev Glatshteyn. Yiddish editors fought major anti-censorship Supreme Court cases during this period, playing a key role in the transnational struggle for a free press. The talk concludes by tracing how the earlier Proletarian poets deeply informed the work of later, experimental Modernist writers. Anna Elena Torres is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Chicago. Her forthcoming book is titled Any Minute Now The World Streams Over Its Border!: Anarchism and Yiddish Literature (Yale University Press). This project examines the literary production, language politics, and religious thought of Jewish anarchist movements from 1870 to the present in Moscow, Tel Aviv, London, Buenos Aires, New York City, and elsewhere. Torres’ work has appeared in Jewish Quarterly Review, In geveb, Nashim, make/shift, and the anthology Feminisms in Motion: A Decade of Intersectional Feminist Media (AK Press, 2018). -

We Remember the Most Tragic Dates for Latvian Jews

BEST WISHES FOR A JOYOUS AND BRIGHT HANUKKAH! WISHING YOU A HAPPY NEW YEAR 2021 December 2020 | Kislev/Tevet 5781 JEWISH SURVIVORS OF LATVIA, INC. Volume 34, No. 3 WE REMEMBER THE MOST TRAGIC DATES FOR LATVIAN JEWS Due to COVID-19, many events are being held in different ways. Similarly, Jewish Survivors of Latvia also could not gather at the Park East Synagogue, as we have for decades to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust in Latvia. But, unlike many sister organizations that decided to host virtual events on Zoom, the JSL Council proposed a different solution. As you may know, we erected a monument several years ago in memory of the Latvian Jews killed during the Holocaust, which is in Brooklyn at the Holocaust Memorial Park and has been in place for many years. Therefore, taking into account the official guidelines regarding outdoor activities (wearing masks, social distancing, etc.), we held our commemoration in this park on November 29, on the eve of the 79th anniversary of the first massacre in Rumbula. Professor G. Schwab not only provided a brief opening for our meeting, but also concluded it with a very informative speech to stand up, JSL member Emil Silberman read a prayer El Mole Rachamim and named JSL members who have passed in the past year: Professor Gertrude Schneider, Sheila Johnson Robbins, Ruth Fitingof, Gita Gurevich, Rozaliya Dumesh, Ludmila Girsheva, Alex Gertzmark, Isaac Gamarnik, Ruvim Udem, Semyon Gitlin. After that, he read the Kaddish for the departed. The upper portion of our stone in the Holocaust Memorial Park Then David Silberman, President of the JSL, gave a short We had the opportunity to lay out an aluminum foil mat and report regarding the activities of our organization in the past year.