Anarchism++PO53022A.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan

I Belong Only to Myself: The Life and Writings of Leda Rafanelli Excerpt from: CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan ...Tracking back a few years, Leda and her beau Giuseppe Monanni had been invited to Milan in 1908 in order to take over the editorship of the newspaper The Human Protest (La Protesta Umana) by its directors, Ettore Molinari and Nella Giacomelli. The anarchist newspaper with the largest circulation at that time, The Human Protest was published from 1906–1909 and emphasized individual action and rebellion against institutions, going so far as to print articles encouraging readers to occupy the Duomo, Milan’s central cathedral.3 Hence it was no surprise that The Human Protest was subject to repeated seizures and the condemnations of its editorial managers, the latest of whom—Massimo Rocca (aka Libero Tancredi), Giovanni Gavilli, and Paolo Schicchi—were having a hard time getting along. Due to a lack of funding, editorial activity for The Human Protest was indefinitely suspended almost as soon as Leda arrived in Milan. She nevertheless became close friends with Nella Giacomelli (1873– 1949). Giacomelli had started out as a socialist activist while working as a teacher in the 1890s, but stepped back from political involvement after a failed suicide attempt in 1898, presumably over an unhappy love affair.4 She then moved to Milan where she met her partner, Ettore Molinari, and turned towards the anarchist movement. Her skepticism, or perhaps burnout, over the ability of humans to foster social change was extended to the anarchist movement, which she later claimed “creates rebels but doesn’t make anarchists.”5 Yet she continued on with her literary initiatives and support of libertarian causes all the same. -

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

Unforgiving Years by Victor Serge (Translated from the French and with an Introduction by Richard Greeman), NYRB Classics, 2008, 368 Pp

Unforgiving Years by Victor Serge (Translated from the French and with an introduction by Richard Greeman), NYRB Classics, 2008, 368 pp. Michael Weiss In the course of reviewing the memoirs of N.N. Sukhanov – the man who famously called Stalin a ‘gray blur’ – Dwight Macdonald gave a serviceable description of the two types of radical witnesses to the Russian Revolution: ‘Trotsky’s is a bird’s- eye view – a revolutionary eagle soaring on the wings of Marx and History – but Sukhanov gives us a series of close-ups, hopping about St. Petersburg like an earth- bound sparrow – curious, intimate, sharp-eyed.’ If one were to genetically fuse these two avian observers into one that took flight slightly after the Bolshevik seizure of power, the result would be Victor Serge. Macdonald knew quite well who Serge was; the New York Trotskyist and scabrous polemicist of Partisan Review was responsible, along with the surviving members of the anarchist POUM faction of the Spanish Civil War, for getting him out of Marseille in 1939, just as the Nazis were closing in and anti-Stalinist dissidents were escaping the charnel houses of Eurasia – or not escaping them, as was more often the case. Macdonald, much to his later chagrin, titled his own reflections on his youthful agitations and indiscretions Memoirs of a Revolutionist, an honourable if slightly wince-making tribute to Serge, who earned every syllable in his title, Memoirs of a Revolutionary. And after the dropping of both atomic bombs on Japan, it was Macdonald’s faith in socialism that began to -

KARL MARX Peter Harrington London Peter Harrington London

KARL MARX Peter Harrington london Peter Harrington london mayfair chelsea Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 43 dover street 100 FulHam road london w1s 4FF london sw3 6Hs uk 020 3763 3220 uk 020 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 eu 00 44 20 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 www.peterharrington.co.uk usa 011 44 20 7591 0220 Peter Harrington london KARL MARX remarkable First editions, Presentation coPies, and autograPH researcH notes ian smitH, senior sPecialist in economics, Politics and PHilosoPHy [email protected] Marx: then and now We present a remarkable assembly of first editions and presentation copies of the works of “The history of the twentieth Karl Marx (1818–1883), including groundbreaking books composed in collaboration with century is Marx’s legacy. Stalin, Mao, Che, Castro … have all Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), early articles and announcements written for the journals presented themselves as his heirs. Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher and Der Vorbote, and scathing critical responses to the views of Whether he would recognise his contemporaries Bauer, Proudhon, and Vogt. them as such is quite another matter … Nevertheless, within one Among this selection of highlights are inscribed copies of Das Kapital (Capital) and hundred years of his death half Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (Communist Manifesto), the latter being the only copy of the the world’s population was ruled Manifesto inscribed by Marx known to scholarship; an autograph manuscript leaf from his by governments that professed Marxism to be their guiding faith. years spent researching his theory of capital at the British Museum; a first edition of the His ideas have transformed the study account of the First International’s 1866 Geneva congress which published Marx’s eleven of economics, history, geography, “instructions”; and translations of his works into Russian, Italian, Spanish, and English, sociology and literature.” which begin to show the impact that his revolutionary ideas had both before and shortly (Francis Wheen, Karl Marx, 1999) after his death. -

Black Flag White Masks: Anti-Racism and Anarchist Historiography

Black Flag White Masks: Anti-Racism and Anarchist Historiography Süreyyya Evren1 Abstract Dominant histories of anarchism rely on a historical framework that ill fits anarchism. Mainstream anarchist historiography is not only blind to non-Western elements of historical anarchism, it also misses the very nature of fin de siècle world radicalism and the contexts in which activists and movements flourished. Instead of being interested in the network of (anarchist) radicalism (worldwide), political historiography has built a linear narrative which begins from a particular geographical and cultural framework, driven by the great ideas of a few father figures and marked by decisive moments that subsequently frame the historical compart- mentalization of the past. Today, colonialism/anti-colonialism and imperialism/anti-imperialism both hold a secondary place in contemporary anarchist studies. This is strange considering the importance of these issues in world political history. And the neglect allows us to speculate on the ways in which the priorities might change if Eurocentric anarchist histories were challenged. This piece aims to discuss Eurocentrism imposed upon the anarchist past in the form of histories of anarchism. What would be the consequences of one such attempt, and how can we reimagine the anarchist past after such a critique? Introduction Black Flag White Masks refers to the famous Frantz Fanon book, Black Skin White Masks, a classic in anti-colonial studies, and it also refers to hidden racial issues in the history of the black flag (i.e., anarchism). Could there be hidden ethnic hierarchies in the main logic of anarchism's histories? The huge difference between the anarchist past and the histories of anarchism creates the gap here. -

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture: Anarchy, the Beats and the Psychedelic Transformation of Consciousness By Ed D’Angelo Copyright © Ed D’Angelo 2019 A much shortened version of this paper appeared as “Anarchism and the Beats” in The Philosophy of the Beats, edited by Sharin Elkholy and published by University Press of Kentucky in 2012. 1 The postwar American counterculture was established by a small circle of so- called “beat” poets located primarily in New York and San Francisco in the late 1940s and 1950s. Were it not for the beats of the early postwar years there would have been no “hippies” in the 1960s. And in spite of the apparent differences between the hippies and the “punks,” were it not for the hippies and the beats, there would have been no punks in the 1970s or 80s, either. The beats not only anticipated nearly every aspect of hippy culture in the late 1940s and 1950s, but many of those who led the hippy movement in the 1960s such as Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were themselves beat poets. By the 1970s Allen Ginsberg could be found with such icons of the early punk movement as Patty Smith and the Clash. The beat poet William Burroughs was a punk before there were “punks,” and was much loved by punks when there were. The beat poets, therefore, helped shape the culture of generations of Americans who grew up in the postwar years. But rarely if ever has the philosophy of the postwar American counterculture been seriously studied by philosophers. -

The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock

Transoceanic Canada: The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock by Matthew Hiebert B.A., The University of Winnipeg, 1997 M.A., The University of Amsterdam, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) The University Of British Columbia (Vancouver) August 2013 c Matthew Hiebert, 2013 ABSTRACT Through a critical examination of his oeuvre in relation to his transoceanic geographical and intellectual mobility, this dissertation argues that George Woodcock (1912-1995) articulates and applies a normative and methodological approach I term “regional cosmopolitanism.” I trace the development of this philosophy from its germination in London’s thirties and forties, when Woodcock drifted from the poetics of the “Auden generation” towards the anti-imperialism of Mahatma Gandhi and the anarchist aesthetic modernism of Sir Herbert Read. I show how these connected influences—and those also of Mulk Raj Anand, Marie-Louise Berneri, Prince Peter Kropotkin, George Orwell, and French Surrealism—affected Woodcock’s critical engagements via print and radio with the Canadian cultural landscape of the Cold War and its concurrent countercultural long sixties. Woodcock’s dynamic and dialectical understanding of the relationship between literature and society produced a key intervention in the development of Canadian literature and its critical study leading up to the establishment of the Canada Council and the groundbreaking journal Canadian Literature. Through his research and travels in India—where he established relations with the exiled Dalai Lama and major figures of an independent English Indian literature—Woodcock relinquished the universalism of his modernist heritage in practising, as I show, a postcolonial and postmodern situated critical cosmopolitanism that advocates globally relevant regional culture as the interplay of various traditions shaped by specific geographies. -

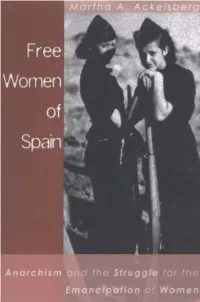

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

Rancour's Emphasis on the Obviously Dark Corners of Stalin's Mind

Rancour's emphasis on the obviously dark corners of Stalin's mind pre- cludes introduction of some other points to consider: that the vozlzd' was a skilled negotiator during the war, better informed than the keenly intelli- gent Churchill or Roosevelt; that he did sometimes tolerate contradiction and even direct criticism, as shown by Milovan Djilas and David Joravsky, for instance; and that he frequently took a moderate position in debates about key issues in the thirties. Rancour's account stops, save for a few ref- erences to the doctors' plot of 1953, at the end of the war, so that the enticing explanations offered by William McCagg and Werner Hahn of Stalin's conduct in the years remaining to him are not discussed. A more subtle problem is that the great stress on Stalin's personality adopted by so many authors, and taken so far here, can lead to a treatment of a huge country with a vast population merely as a conglomeration of objects to be acted upon. In reality, the influences and pressures on people were often diverse and contradictory, so that choices had to be made. These were simply not under Stalin's control at all times. One intriguing aspect of the book is the suggestion, never made explicit, that Stalin firmly believed in the existence of enemies around him. This is an essential part of the paranoid diagnosis, repeated and refined by Rancour. If Stalin believed in the guilt, in some sense, of Marshal Tukhachevskii et al. (though sometimes Rancour suggests the opposite), then a picture emerges not of a ruthless dictator coldly plotting the exter- mination of actual and potential opposition, but of a fear-ridden, tormented man lashing out in panic against a threat he believed to real and immediate. -

TAZ, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism.Pdf

T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey Autonomedia Anti-copyright, 1985, 1991. May be freely pirated & quoted-- the author & publisher, however, would like to be informed at: Autonomedia P. O. Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Book design & typesetting: Dave Mandl HTML version: Mike Morrison Printed in the United States of America Part 1 T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CHAOS: THE BROADSHEETS OF ONTOLOGICAL ANARCHISM was first published in 1985 by Grim Reaper Press of Weehawken, New Jersey; a later re-issue was published in Providence, Rhode Island, and this edition was pirated in Boulder, Colorado. Another edition was released by Verlag Golem of Providence in 1990, and pirated in Santa Cruz, California, by We Press. "The Temporary Autonomous Zone" was performed at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, and on WBAI-FM in New York City, in 1990. Thanx to the following publications, current and defunct, in which some of these pieces appeared (no doubt I've lost or forgotten many--sorry!): KAOS (London); Ganymede (London); Pan (Amsterdam); Popular Reality; Exquisite Corpse (also Stiffest of the Corpse, City Lights); Anarchy (Columbia, MO); Factsheet Five; Dharma Combat; OVO; City Lights Review; Rants and Incendiary Tracts (Amok); Apocalypse Culture (Amok); Mondo 2000; The Sporadical; Black Eye; Moorish Science Monitor; FEH!; Fag Rag; The Storm!; Panic (Chicago); Bolo Log (Zurich); Anathema; Seditious Delicious; Minor Problems (London); AQUA; Prakilpana. Also, thanx to the following individuals: Jim Fleming; James Koehnline; Sue Ann Harkey; Sharon Gannon; Dave Mandl; Bob Black; Robert Anton Wilson; William Burroughs; "P.M."; Joel Birroco; Adam Parfrey; Brett Rutherford; Jake Rabinowitz; Allen Ginsberg; Anne Waldman; Frank Torey; Andr Codrescu; Dave Crowbar; Ivan Stang; Nathaniel Tarn; Chris Funkhauser; Steve Englander; Alex Trotter. -

Contemporary Anarchist Studies

Contemporary Anarchist Studies This volume of collected essays by some of the most prominent academics studying anarchism bridges the gap between anarchist activism on the streets and anarchist theory in the academy. Focusing on anarchist theory, pedagogy, methodologies, praxis, and the future, this edition will strike a chord for anyone interested in radical social change. This interdisciplinary work highlights connections between anarchism and other perspectives such as feminism, queer theory, critical race theory, disability studies, post- modernism and post-structuralism, animal liberation, and environmental justice. Featuring original articles, this volume brings together a wide variety of anarchist voices whilst stressing anarchism’s tradition of dissent. This book is a must buy for the critical teacher, student, and activist interested in the state of the art of anarchism studies. Randall Amster, J.D., Ph.D., professor of Peace Studies at Prescott College, publishes widely in areas including anarchism, ecology, and social movements, and is the author of Lost in Space: The Criminalization, Globalization , and Urban Ecology of Homelessness (LFB Scholarly, 2008). Abraham DeLeon, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at the University of Rochester in the Margaret Warner Graduate School of Education and Human Development. His areas of interest include critical theory, anarchism, social studies education, critical pedagogy, and cultural studies. Luis A. Fernandez is the author of Policing Dissent: Social Control and the Anti- Globalization Movement (Rutgers University Press, 2008). His interests include protest policing, social movements, and the social control of late modernity. He is a professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northern Arizona University. Anthony J. Nocella, II, is a doctoral student at Syracuse University and a professor at Le Moyne College. -

The Rise of Ethical Anarchism in Britain, 1885-1900

1 e[/]pater 2 sie[\]cle THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 By Mark Bevir Department of Politics Newcastle University Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU U.K. ABSTRACT In the nineteenth century, anarchists were strict individualists favouring clandestine organisation and violent revolution: in the twentieth century, they have been romantic communalists favouring moral experiments and sexual liberation. This essay examines the growth of this ethical anarchism in Britain in the late nineteenth century, as exemplified by the Freedom Group and the Tolstoyans. These anarchists adopted the moral and even religious concerns of groups such as the Fellowship of the New Life. Their anarchist theory resembled the beliefs of counter-cultural groups such as the aesthetes more closely than it did earlier forms of anarchism. And this theory led them into the movements for sex reform and communal living. 1 THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 Art for art's sake had come to its logical conclusion in decadence . More recent devotees have adopted the expressive phase: art for life's sake. It is probable that the decadents meant much the same thing, but they saw life as intensive and individual, whereas the later view is universal in scope. It roams extensively over humanity, realising the collective soul. [Holbrook Jackson, The Eighteen Nineties (London: G. Richards, 1913), p. 196] To the Victorians, anarchism was an individualist doctrine found in clandestine organisations of violent revolutionaries. By the outbreak of the First World War, another very different type of anarchism was becoming equally well recognised. The new anarchists still opposed the very idea of the state, but they were communalists not individualists, and they sought to realise their ideal peacefully through personal example and moral education, not violently through acts of terror and a general uprising.