The Pottery Production Centre of Speicher-Herforst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gastgeber 2019

WILLKOMMEN | WELKOM |WELCOME | BIENVENUE Erlebnis mit präsentiert: Gehen Sie gemeinsam mit uns auf Entdeckungsreise und GB | Go with us on a discovery trip and get to know the Süd EIFEL lernen Sie die Vielfalt unserer Ferienregion kennen. diversity of our holiday region. Die Tourist-Informationen und Gastgeber der Südeifel freu- The tourist informations and hosts of the Südeifel are loo- en sich auf Ihren Besuch! king forward to your visit! NL | Wij nodigen u uit met ons op ontdekking te gaan en FR | Partez avec nous en voyage découverte et découvrez la de rijkdom van onze regio te leren kennen. diversité de notre région de vacances. Eifel besuchen... De toeristische diensten en onze gastheren zien uit naar uw Les offices de tourisme et les hôtes du Südeifel se réjouis- bezoek! sent de votre visite! INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Seite 2 FERIENREGION ARZFELD Tauchen Sie ein TOURIST-INFORMATION ARZFELD Luxemburger Straße 5 | 54687 Arzfeld Tel. +49 (0) 6550/961080 | Fax +49 (0) 6550/961082 in die Welt von [email protected] | www.islek.info Gerolsteiner! Seite 8 FERIENREGION BITBURGER LAND – Was macht unser Mineralwasser so besonders? BITBURG | SPEICHER | KYLLBURG Kommen Sie vorbei und finden es heraus! TOURIST-INFORMATION BITBURGER LAND Unsere Besucherführungen (nur für Gruppen) finden ganzjährig montags bis freitags um 9, 11 und 13 Uhr Tourist-Informationen in Bitburg und Kyllburg mit vorheriger Anmeldung statt. Römermauer 6 | 54634 Bitburg Für Spontanbesucher (Einzelpersonen und Familien) Zentrale Rufnummer +49 (0) 6561/94340 gibt es wochentags jeweils -

Es Freut Uns, Ihnen Die Verbandsgemeinde Speicher Vorstellen Zu Dürfen

Es freut uns, Ihnen die Verbandsgemeinde Speicher vorstellen zu dürfen: Links eingebettet in die reizvolle Kylllandschaft, umgeben von großen Waldgebieten, liegt auf einem 300 bis 350 m hohen Plateau die VERBANDSGEMEINDE SPEICHER. Sie gehört zum südwestlichen Teil des Landkreises Bitburg-Prüm in direkter Nachbar- schaft zu Luxemburg. Mit einer Fläche von 60,06 km² umfasst sie die Ortsgemeinden Auw a. d. Kyll, Beilingen, Herforst, Hosten, Orenhofen, Philippsheim, Preist, Spangdah- lem und Speicher mit insgesamt rd. 8.300 meldepflichtigen Einwohnern sowie rd. 6.000 Angehörigen der US-Streitkräfte des Flugplatzes Spangdahlem. Das Gebiet der Verbandsgemeinde Speicher war in allen Epochen der Vorgeschichte von der Jungsteinzeit bis zur La-Tene-Kultur besiedelt. Den Römern – sie entdeckten die reichen Lager weißen und grauen Tons des Speicherer Raumes - ist die Entwick- lung einer gegen Ende des ersten und zu Beginn des zweiten Jahrhunderts n. Chr. blühenden Töpferindustrie zu verdanken, die bis in die Gegenwart als heimische Indust- rie - vor allem in der Ortsgemeinde Speicher – fortlebt und fortwirkt. Zahlreiche im Speicherer Wald ausgegrabene Öfen und Tonwarenfunde zeugen von einer umfangrei- chen Fertigung von Tonwaren und Ziegeln bis ins 5. Jh. hinein. Nach einigen Jahrhun- derten der Stagnation, wurde erst um die Jahrtausendwende die wirtschaftliche Herstel- lung von Tonerzeugnissen wieder aufgenommen, die schließlich im 14. Jh. ihre Blüte erreichte. Wahrscheinlich hat eine Ursprungssiedlung der heutigen Stadt „Speicher“ bereits um 1000 bestanden; jedenfalls existierte im Jahre 1075 hier eine Pfarrkirche. 1136 nennt eine Urkunde erstmals den Namen der Ortschaft. Die inzwischen wieder betriebenen Speicherer Töpfereien werden 1293 urkundlich erwähnt und im Jahre 1485 wurde sogar eine Krugbäckerzunft offiziell gegründet. -

Modellregion Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm Das Modellvorhaben

Modellvorhaben Langfristige Sicherung von Versorgung und Mobilität in ländlichen Räumen Modellregion Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm Ziele – Vorgehen – Ergebnisse Das Modellvorhaben Mit dem Modellvorhaben leistet das Bundes Zu den Zielgruppen zählen u. a. Jugendliche, ministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur Familien mit Kindern und Senioren. Durch ihre einen Beitrag dazu, gleichwertige Lebensverhält aktive Einbindung können ihre Ideen aufge nisse in ländlichen Räumen zu gewährleisten. nommen und die Akzeptanz und Effizienz von Es soll die 18 Modellregionen dabei unterstützen, künftigen Lösungen gefördert werden. Daseinsvorsorge, Nahversorgung und Mobilität besser zu verknüpfen, um die Lebensqualität in Je nach Ausgangsbedingungen variiert der der Region zu verbessern und wirtschaftliche strategische Ansatz des Modellvorhabens in den Entwicklung zu ermöglichen. einzelnen Regionen. Während ein Konzept zur Bündelung von Standorten der Daseinsvorsorge In dem Modellvorhaben wird besonderer Wert in „Kooperationsräumen“ eher nur mittel- bis darauf gelegt, dass neben Politik, Verwaltung, langfristig umgesetzt werden kann, wird sich Zivilgesellschaft sowie Anbietern von Daseins ein integriertes Mobilitätskonzept auch schon vorsorgedienstleistungen und Nahversorgung in kürzerer Frist auf die vorhandene Verteilung von Beginn an auch die verschiedenen Ziel und der Daseinsvorsorgeeinrichtungen ausrichten Nutzergruppen vor Ort aktiv in die Entwicklung können. In Verbindung mit dem Kooperations und Umsetzung von Standortkonzepten und raumkonzept -

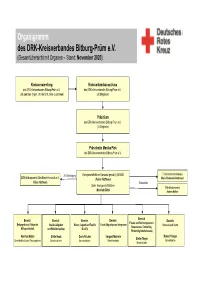

Organigramm Des DRK-Kreisverbandes Bitburg-Prüm E.V

Organigramm des DRK-Kreisverbandes Bitburg-Prüm e.V. (Gesamtübersicht mit Organen – Stand: November 2020) Kreisversammlung Kreisverbandsausschuss des DRK-Kreisverbandes Bitburg-Prüm e.V. des DRK-Kreisverbandes Bitburg-Prüm e.V. (als oberstes Organ, tritt alle fünf Jahre zusammen) (39 Mitglieder) Präsidium des DRK-Kreisverbandes Bitburg-Prüm e.V. (16 Mitglieder) Präsidentin Monika Fink des DRK-Kreisverbandes Bitburg-Prüm e.V. 25% Beteiligung Kreisgeschäftsführer/Vorstand gemäß § 26 BGB IT (Informationstechnologie) DRK-Bildungswerk Eifel-Mosel-Hunsrück e.V. Rainer Hoffmann Mario Pawlowski-Großmann Klaus Hofmann Stabsstellen Stellv. Kreisgeschäftsführer Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Manfred Böttel Andrea Kalkes Bereich Bereich Bereich Bereich Bereich Bereich Finanz- und Rechnungswesen, Rettungsdienst / Nationale Soziale Aufgaben Kinder, Jugend und Familie Flucht, Migration und Integration Personal und Recht Steuerwesen, Controlling, Hilfsgesellschaft und Wohlfahrtspflege (KiJuFa) Fördermitgliederbetreuung Manfred Böttel Ulrike Haab Doris Rücker Irmgard Mminele Robert Olinger Stefan Meyer Bereichsleiter/Leiter Rettungsdienst Bereichsleiterin Bereichsleiterin Bereichsleiterin Bereichsleiter Bereichsleiter Organigramm des DRK-Kreisverbandes Bitburg-Prüm e.V. Kreisgeschäftsführer/Vorstand gemäß § 26 BGB Rainer Hoffmann Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und MGH Stabsstelle Stabsstelle IT (Informationstechnologie) Andrea Kalkes Stellv. Kreisgeschäftsführer und Projekte Manfred Böttel Mario Pawlowski-Großmann Bereich Bereich G Rettungsdienst / Nationale Bereich Bereich -

Lunch at Bitburg Air Force Base, Bitburg, Germany, Josh/Rv (8) Box: 207

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF from our textual collections. Collection: Speechwriting, White House Office of: Research Office, 1981-1989 Folder: 05/05/1985 Remarks: Lunch at Bitburg Air Force Base, Bitburg, Germany, Josh/Rv (8) Box: 207 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing ·:--... ""' --~. .- ~ \ \. ';> I ' -·' -\ .. -:,,..\ ' ~ 1: BITBlJFlG Bitburg, county capital of the Southern Eitel, located In the hills iroximity to the Benelux countries, Bitburg offers ideal settlement between the Kyll and the Nims rivers, has been for centuries the opportunities. Located at the intersection of several Federal high natural center of this predominantly agriculturally-oriented area. ways at only 27 KM from the central- and university city of Trier, the city will soon have good traffic connections with Antverp, Brussels, Among the many county Liege, and the Rhein-Main/Rhein-Neckar area via Federal Auto capitals of Rheinland Pfalz, the almost 2000-ynar bahn A-60. With the Beginning of the construction work on the new old Eifel city has an espe A-60 between German border and Bitburg, and the soon to follow cially interesting past. Age continuation up to Witllich (A-48) this traffic improvement plan has old East-West roads cross entered a decisive stage. here with the most impor tant North-South connec As the capital of Bitburg-Pr0m County, Bitburg is today the econo tion through! the Eifel from mic and cultural c'ent;r of the Southern Eitel. -

Fahrplan L403

gültig ab 01.02.20 403H Bitburg-Dudeld./Speicher-Spangd.-Binsfeld-(Wittlich) Verkehrstage Montag - Freitag Fahrtnummer 1 3 7 201 9 11 13 15 17 19 25 27 Verkehrshinweise S S kB S S S S S K Bitburg Edith Stein HS 7:25 Bitburg ZOB 7:33 10:45 11:30 Bitburg Karenweg 7:36 10:47 11:32 Bitburg Kath. Schule Bitburg Karenweg Bitburg GS Nord Bitburg GS Süd Bitburg ZOB Bitburg Karenweg Bitburg Maximiner Wäldchen Bitburg Echternacher Str. Bitburg Ostring Bitburg Am Sportplatz Bitburg GS Süd Bitburg Saarstraße 10:48 Bitburg Bosch-Riewer 10:49 Bitburg Flugpl. Eifelstern Bitburg Mötscher Straße Bitburg Spangd. Str. Masholder B51 Abzw. 10:50 Bitburg Flugplatz Abzw. 10:52 Eßlingen Abzw. K39 10:56 Mötsch Wasserturm Mötsch Gasth. Weiler Mötsch am KG Mötsch Wasserturm Bitburg Monental Hüttingen Bahnhof Hüttingen Wendepl. Bitburg Albachmühle Metterich Kuhberg 7:44 11:41 Metterich Brandweiher 7:36 11:43 Metterich Friedhof 7:37 11:44 Gondorf Abzw. 7:46 11:48 Dudeldorf Ort Gondorf Ort 7:45 11:50 Gondorf Abzw. Park 7:46 11:52 Dudeldorf Ort 11:56 Dudeldorf GS 7:51 Dudeldorf KG 7:52 Dudeldorf Ordorfer Brücke Pickließem Ort Philippsheim Bahnhof 7:30 Philippsheim Laymühle 7:31 Scharfbillig Ort 7:28 10:59 Röhl Nagelstraße 7:32 Röhl Sportplatz 11:01 Sülm Röhler Straße 7:36 11:03 Sülm Kiga Röhl Sportplatz 8:22 8:22 Röhl Nagelstraße 8:24 8:24 Scharfbillig Ort 8:27 8:27 Dahlem Brücke 7:41 Dahlem Gemeindehaus 7:42 Trimport Ort 7:45 11:08 Dahlem Brücke 11:11 Idenheim Kirche 7:49 Idenheim Ort Idesheim GS 7:56 Sülm Kiga 8:30 8:30 Spangdahlem Hauptstraße 7:56 Spangdahlem Neustraße 7:58 Spangdahlem Trierer Str. -

Unclassified Xxix S E C\E T

A. Fighter; Total claims against enemy aircraft during the month were 39-0-13 in the air and 1-0-2 on the ground. Missions 25 Sorties 296 d. Flak.— XIX TAC aircraft losses for the month because of flak Tons Bombs on Tgts 128 were unusually high. Out of the 50 aircraft lost, 35 were victims of Tons Frags 14.69 flak. The enemy, realizing that the greatest threat to the success of Tons Napalm 7.15 its ARD3NNBS salient was American air power, built up a very strong Tons Incendiaries 10.25 anti-aircraft defense around the entire area. Rockets 22 Claims (air) 4-1-1 The TTY TAC A-2 Flak Officer, reporting near the end of the Geraan retreat from the Bulge area, said: B. Reconnaissance: "The proportion of flak protection to troops and area involved (in Tac/R Sorties 58/36 1. INTRODUCTION. the ARDENNES area) was higher than in any previous operation in this P/R Sorties 7/6 war's history. Artillery sorties 4/2 a. General.— opening the year of 1945, the XIX Tactical Air Com mand-Third US Army team had a big job on its hands before it could re "Flak units were apparently given the highest priorities in supply C. Night Fighter: sume the assault of the SIEGFRIED LINE. The German breakthrough into of fuel and ammunition. They must also have been given a great degree of the ARDENNES had been checked but not yet smashed. The enemy columns freedom in moving over roads always taxed to capacity. Sorties 15 which had surged toward the MEUSE were beginning to withdraw, for the Claims (air) 1-0-0 v wily Rundstedt's best-laid plans had been wrecked on the rock of BAS "In addition to the tremendous quantities of mobile flak assigned TOGNS. -

Locations Page

Culligan water delivery is available to all areas listed below. Germany Aschafenburg Darmstadt: Hanau: Ansbach/Katterbach Cambri Fritsch Kaserne Cardwell Housing Bleidorn Housing Jefferson Housing Fliegerhorst Kaserne Bleidorn Leased Kelly Barracks Katterbach Housing Lincoln Housing Langenselbold Bismarke Housing Santa Barbara Housing New/Old Argonner Housing Bochberg Housing Langen Pioneer Kaserne Heilsbronn Housing Area Wolfgang Kaserne Lichtenau Dexheim Yorkhof Housing Shipton Housing Friedberg: Heidelberg: Babenhausen McArthur Housing Campbell Barracks Bad Kissingen Ray Barracks Hammon Barracks Bad Nauheim Kilbourne Kaserne Geibelstadt Mark Twain Village Bamberg: Geilenkirchen Nachrichten Kaserne Flynn Housing Patrick Henry Village Flynn Kaserne Gelnhausen: Patton Barracks Coleman Barracks Stem Kaserne Baumholder: Randy Hubbard Kaserne Tompkins Barracks Birkenfeld Housing Champion Housing Giessen: Heidelberg Off Post: Hoppstadten Housing Alvin York Housing Eppenheim Neubruecke Housing Dulles Housing Leimen Smith Housing Marshall Housing Nussloch Strassburg Housing Plankstadt Wetzel Housing Grafenwoehr Sandhausen Schwetzingen Bitburg & Housing Grafenwoehr Off Post: Seckenheim Freihung St. Iligen Buedingen: Kaltenbrunn St. Leon Rot Armstrong Housing Schwarzenbach Tanzfleck Butzbach: Romanway Housing Griesheim Griesheim Housing Griesheim Leased Hohenfels: Sembach Airbase Wuerzburg: Amberg Faulenburg Kaserne Grossbissendorf Spangdahlem & Housing: Heuchelhof Hoermannsdorf Binsfeld Housing Leighton Barracks Hohenburg Herforst Housing Lincoln -

Erfolgsmodell Eifelkreis

ERFOLGSMODELL EIFELKREIS ZUKUNFTS-CHECK DORF UND KREISENTWICKLUNGSKONZEPT Der Zukunfts-Check Dorf und das Kreisentwick- lungskonzept im Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm werden Informationen zur gefördert durch das Ministerium des Innern und Kommunalentwicklung für Sport. in Rheinland-Pfalz finden Das Modellvorhaben Langfristige Sicherung von Sie auch im Internet: Versorgung und Mobilität wird gefördert durch www.mdi.rlp.de das Bundesministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur. ERFOLGSMODELL EIFELKREIS ZUKUNFTS-CHECK DORF UND KREISENTWICKLUNGSKONZEPT Inhalt Vorworte 2-3 Halbzeitkonferenz Zukunfts-Check 10 Zukunfts-Check Dorf im Eifelkreis 4 Kreisentwicklungskonzept Eifelkreis 11-13 Besuchsdienst Rittersdorf 5 Konversion und Baukultur 14 Markt-Treff Mötsch 6 Mobilität und Versorgung 15 Fotoausstellung Buchet 7 Bürgerbeteiligung 16 Mittagstisch Lasel 8 medicus, Eifler Ärzte eG 17-18 Demografie Exzellenz Award 9 Infrastrukturatlas 19 Planung ZCD Kommunen in Rheinland-Pfalz stehen in den Viele aktive Bürgerinnen und Bürger, die Verwal- kommenden Jahren vor der Herausforderung, tung und die politisch Verantwortlichen haben sich im Wettbewerb um Einwohnerinnen und diese Chance genutzt. Es ist kein vorgefertigtes Einwohner, Unternehmen, private Investitionen, Programm, das abzuarbeiten ist, sondern es gilt, öffentliche Institutionen sowie Freizeit- und individuelle Lösungen zu gestalten, die passen. Kultureinrichtungen als attraktive Wohn- und Arbeitsstandorte zu positionieren. In dieser Broschüre möchte ich Ihnen gemeinsam mit Landrat Dr. Joachim Streit die Aktivitäten Mit integrierten Entwicklungsprozessen haben im Eifelkreis vorstellen und zum Nachahmen Städte und Gemeinden, Regionen, Kreise und motivieren. Gerne wird das Innenministerium im Verbandsgemeinden die Chance, sich zukunfts- Rahmen der Strukturentwicklung interessierte fähig aufzustellen. Mit der gleichzeitigen Einbin- Kommunen hierbei unterstützen. dung aller Handlungsfelder und Akteure werden eine Vielzahl von Interessen und Themen in eine klare Zielsetzung eingeordnet. -

BITBURG · GEROLSTEIN · NEUERBURG Aus Dem

neUES Frühjahr/Sommer 2012 NEUESAUS DEM MARIENHAUS KLINIKUM EI FEL BITBURG · GEROLSTEIN · NEUERBURG EIN KLINIKUM – DREI STANDORTE Marienhaus Klinikum Eifel im Klinikverbund Bitburg, Gerolstein, Neuerburg Kyphoplastie Rheumatologie Phase F Im Marienhaus Klinikum Eifel können „Eine frühe Erkennung und Behandlung „Bei uns kommt die Intensivstation zu Patienten mit Wirbelbrüchen hoch- ist bei Rheuma sehr wichtig.“ den Patienten.“ Das Marienhaus Klini- effizient durch drei verschiedene Me- Dr. Manfred Rittich ist Facharzt für kum Eifel bietet am Standort Neuer- thoden der Kyphoplastie behandelt Rheumatologie am Marienhaus Klini- burg eine Pflegeeinrichtung für Men- werden. kum Eifel St. Elisabeth Gerolstein. schen mit schweren Hirnschädigungen und/oder Langzeitbeatmung. Seite 4 Seite 5 Seite 8 2 neUES Frühjahr/Sommer 2012 NEUES Frühjahr/Sommer 3 .................................. ................................... „Ich danke Ihnen allen für Ihr Vertrauen und GENAUE DIAGNOSEN IN ABSCHIED UND NEUBEGINN das gute Miteinander, das Sie mir in den ver- KÜRZESTER ZEIT Verabschiedung von Schwester M. Scholastika Theissen und gangenen elf Jahren entgegen gebracht ha- Editorial ben“, sagte Schwester Scholastika gerührt Karl-Heinz Schmeier sowie personelle Veränderungen im Liebe Leserin, lieber Leser, Patienten profitieren von der Vernetzung innerhalb der bei ihrer Abschiedsrede. Klinikstandorte Verbunddirektorium wir freuen uns, Ihnen nun die aktuelle Die Nachfolge von Sr. M. Scholastika Theissen Ausgabe unseres Klinikmagazins NEUES BitbUrg. Was als digitales Röntgen 2005 Auch angeschlossene Arztpraxen haben sich tritt Helga Beck an. Sie ist damit die erste aus dem Marienhaus Klinikum Eifel prä- im Bitburger Krankenhaus begann, hat sich für eine digitale Anbindung mit dem Marien- weltliche Krankenhausoberin im Verbundkli- sentieren zu können. Es erwartet Sie ein in den vergangenen sieben Jahren zu einer haus Klinikum Eifel entschieden. -

Familienbuch Lahr/Eifel Mit: Hüttingen, Ober

Veröffentlichungen der Westdeutschen Gesellschaft für Familienkunde e.V., Sitz Köln Band 344 Familienbuch Lahr/Eifel mit: Hüttingen, Ober- und Niedergeckler, sowie Bierendorf circa 1640 – 1908 Bearbeitet von Walter Bretz, Bitburg Deutsche Ortssippenbücher der Zentralstelle für Personen- und Familiengeschichte Nr. 2.235 Westdeutsche Gesellschaft für Familienkunde e.V., Köln 2020 Anschrift des Bearbeiters: Walter Bretz Am Eisweiher 10 54634 Bitburg E-Mail: [email protected] Titel: Wappen der Gemeinde Lahr Blasonierung: „Unter goldenem Schildhaupt, darin blaue Wellen- leiste, von Rot über Silber schräglinks geteilt, vorn schräglinke silberne Armbrust, hinten drei schräglinke eingekerbte Tatzen- kreuze mit rotem Pfahl und blauen Balken.“ AGS: 07 2 32 073 Geo-Koordinaten: 49° 56′ 39″ N, 6° 17′ 28″ E // 49.944167°, 6.291111° Layout und Karl G. Oehms Druckvorlage Pfalzgrafenstraße 2, 54293 Trier Copyright: © 2020 by Westdeutsche Gesellschaft für Familienkunde e.V. Geschäftsführung: Karl-Heinz Bernardy Deutschherrenstraße 42, 56070 Koblenz Herstellung: johnen-druck GmbH & Co. KG, 54470 Bernkastel-Kues Einband: Buchbinderei Schwind Trier Bestellung: http://www.shop.wgff.de Internet: http://www.wgff.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Kein Teil dieses Buches darf in irgendeiner Form (Druck, Fotoko- pie, oder in einem anderen Verfahren) ohne schriftliche Genehmigung der Westdeutschen Gesellschaft für Familienkunde oder des Verfassers reproduziert oder unter Verwendung elektronischer Systeme verarbeitet, vervielfältigt oder verbreitet werden. Dieser Regelung -

Funde Und Ausgrabungen Im Bezirk Trier 41, 2009

32 Bernd Bienert BerndDie Bienertspätantike Langmauer in der Südeifel Vier Anschnitte zwischen Herforst (Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm) und Zemmer (Kreis Trier-Saarburg) Für Maximilian *10. März 2010 1 Verlauf der Langmauer. Anschnitte: 1-2 Herforst. 3-4 Forst Arenberg. Die Langmauer, auch Landmauer genannt, umschließt in der Südei- fel beiderseits des unteren Kylltales nordwestlich von Trier auf einer Länge von 72 km ein Gebiet von 220 km2. Im Westen folgt sie auf einer Länge von rund 20 km der Bundesstraße 51. Bei Bitburg/Erdorf wird auf gegenüberliegenden gratartigen Berghängen das Kylltal über- wunden. Von Spangdahlem kommend führt sie mitten durch Herforst hindurch. Westlich der erst seit 1843 bestehenden Kreisstraße setzt sie sich nach Süden fort, bricht im Forst Arenberg nach Osten aus, läuft um Rothaus herum und steuert dann auf Zemmer zu (Steinhausen 1932) [ Abb. 1 ]. Neuesten Erkenntnissen zufolge ist der ummauerte Bezirk zwi- schen zwei Straßen eingebunden. Bei der westlichen Trasse handelt es sich um die von Trier nach Köln führende Römerstraße, bei der östlichen um eine bei Föhren von der Römerstraße Trier-Andernach abzweigende Nebenstrecke. An Zemmer, Binsfeld und Spangdahlem vorbei lief sie auf Schwarzenborn zu, durchzog das Langenthal, über- wand bei Mürlenbach die Kyll und traf bei Weißenseifen auf die Rö- merstraße Trier-Köln. Kapelle und streifenhausartige Bebauung bei Binsfeld wurden jüngst für eine Straßensiedlung (vicus) in Anspruch genommen (Krauße 2006, 281; 380 Liste 10 FSt. 56). Wie aus der Ori- entierung der noch bis in das 5. Jahrhundert hinein produzierenden Speicherer Töpfereien zu erschließen ist, wurde der Vertrieb ihrer Pro- dukte maßgeblich über die Trasse der Nebenstrecke abgewickelt.