Project Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of California San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Infrastructure, state formation, and social change in Bolivia at the start of the twentieth century. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Nancy Elizabeth Egan Committee in charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Chair Professor Michael Monteon, Co-Chair Professor Everard Meade Professor Nancy Postero Professor Eric Van Young 2019 Copyright Nancy Elizabeth Egan, 2019 All rights reserved. SIGNATURE PAGE The Dissertation of Nancy Elizabeth Egan is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ___________________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2019 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE ............................................................................................................ iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ vii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................... ix LIST -

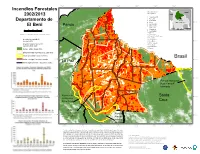

Incendios Forestales 2002/2013 Departamento De El Beni

68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 62°W Incendios Forestales municipalidades/ Brazil municipalities Peru 2002/2013 1 Guayaramerín 2 Riberalta 3 Santa Rosa El Beni Departamento de 11°S 4 Reyes B O L I V I A 11°S 5 San Joaquín Pando 6 Puerto Siles El Beni 1 7 Exaltacion Paraguay 0 25 50 75 100 2 8 Magdalena Chile Argentina Km 9 San Ramón 10 Baures escala 1/4.100.000,Lamber Conformal Conic 11 Huacaraje 12 Santa Ana de Yacuma 13 San Javier incendio forestal 2013/ 14 San Ignacio 12°S hot pixel 2013 15 San Borja 12°S 16 Rurrenabaque incendio forestal 2002-2012/ 17 Trinidad hot pixel 2002-2012 18 San Andrés 6 19 Loreto bosque 2005 / forest 2005 población indígena/indigenous settlement 7 areas protegidas / protected area 8 Brasil limite municipal / municipal border 13°S 5 13°S limite departamental / regional boundary La Paz 4 3 9 10 11 14°S 14°S 1 Parque Nacional Noel Kempff 12 13 Mercado 16 17 15°S Reserva de 15 Santa 15°S la Biosfera Pilon Lajas Cruz 14 19 18 Reserva de la Biosfera Parque 16°S 16°S del Beni Nacional Isiboro Secure 68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 62°W 61°W *Cada incendio forestal representa el punto central de un píxel 1km2 de MODIS, por lo que el incendio detectado se puede situar en cualquier lugar dentro del área de 1km2. Si el punto central del pixel (y por tanto el lugar del incendio reportado) está dentro del bosque, pero a menos de 500m de la frontera forestal, existe la posibilidad de que el incendio haya ocurrido realmente fuera del bosque a lo largo de Fuente de Datos: Cobertura Forestal ~1990~2005 (Conservation International) la frontera forestal. -

Lista De Modificaciones Del 25/12/2020 Al 31/12/2020

Lista de Modificaciones del 25/12/2020 al 31/12/2020 SOLICITUD ENTIDAD DESCRIPCIÓN 1 1234 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Tito Yupanqui 1 1244 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nazacara de Pacajes 2 1234 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Tito Yupanqui 2 1820 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Exaltación 5 0423 Caja de Salud del Servicio Nal. de Caminos y Ramas Anexas 7 1223 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Villa Libertad Licoma 9 1223 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Villa Libertad Licoma 11 0423 Caja de Salud del Servicio Nal. de Caminos y Ramas Anexas 12 0423 Caja de Salud del Servicio Nal. de Caminos y Ramas Anexas 12 1242 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Charaña 13 1223 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Villa Libertad Licoma 14 1223 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Villa Libertad Licoma 15 1223 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Villa Libertad Licoma 16 1223 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Villa Libertad Licoma 28 1274 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Santiago de Machaca 29 1274 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Santiago de Machaca 30 1274 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Santiago de Machaca 52 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva Esperanza 53 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva Esperanza 54 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva Esperanza 55 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva Esperanza 56 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva Esperanza 57 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva Esperanza 58 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva Esperanza 59 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva Esperanza 60 1913 Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Nueva -

Bolivia PRESENTACIÓN INSTITUCIONAL

AUDIENCIA FINAL DE RENDICIÓN PÚBLICA DE CUENTAS 2017 Cochabamba – Bolivia PRESENTACIÓN INSTITUCIONAL RESULTADOS RELEVANTES GESTIÓN 2017 Se han incorporado 131,3 MW al SIN a través de los Proyectos: Hidroeléctrico Misicuni; Solar Yunchará y Termoeléctricas del Beni. Se construyeron en total 466,76 km en Líneas de Transmisión. Se registraron 92.418 clientes nuevos de las distribuidorasde la corporación. PRINCIPALES PROYECTOS CONCLUIDOS GESTIÓN 2017 Etapa: En Operación Comercial Ubicación: Cochabamba Empresa Ejecutora: ENDE MATRIZ Tipo de Energía: Hidroeléctrica Costo Total (Bs): 982,7 Millones Potencia Efectiva: 120 MW Inicio Operación: Septiembre 2017 Impacto: *Incrementar la cap. instalada del SIN *Mejorar la matriz energética *Incrementar la participación de energías renovables *Reducir los subsidios al sector *Liberar gas natural para exportación Etapa: Concluido Ubicación: Tarija Empresa Ejecutora: ENDE GUARACACHI S.A. Tipo de Energía: Solar Fotovoltaica Costo Total (Bs): 66,73 Millones Potencia Efectiva: 5 MW Fecha Inicio: 2015 Inicio Operación: 2017 Impacto: *Inyectar energía eléctrica al SIN *Beneficiar a toda la población conectada al sistema Etapa: En Operación Comercial Ubicación: Beni Empresa Ejecutora: ENDE MATRIZ Tipo de Energía: Termoeléctrica – Diésel Costo Total (Bs): 15,28 Millones Potencia Efectiva: 6,3 MW Fecha Inicio: Ene 2016 Potencia Efectiva Localidades N° Usuarios Finalización: Oct 2017 (kW) Operación: Dic 2017 Rurrenabaque 1.800 3.105 Yucumo 350 1.421 Impacto: San Borja 1.800 4.594 *Mejorar la generación y distribución San Ignacio de Moxos 730 2.659 de energía eléctrica para garantizar la calidad y confiabilidad del servicio en Santa Ana del Yacuma 1.620 2.734 diversas poblaciones del Beni. Total 6.300 14.513 * T Media Etapa: En Operación Comercial Empresa Ejecutora: ENDE Transmisión S.A. -

9782746964303.Pdf

LA VERSION COMPLETE DE VOTRE GUIDE BOLIVIE 2013 en numérique ou en papier en 3 clics à partir de 8.99€ Disponible sur AUTEURS ET DIRECTEURS DES COLLECTIONS Dominique AUZIAS & Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE DIRECTEUR DES EDITIONS VOYAGE Bienvenidos Stéphan SZEREMETA RESPONSABLES EDITORIAUX VOYAGE Patrick MARINGE et Morgane VESLIN a Bolivia ! EDITION ✆ 01 72 69 08 00 Julien BERNARD, Alice BIRON, Audrey BOURSET, Jeff BUCHE, Sophie CUCHEVAL, Linda INGRACHEN, Caroline MICHELOT, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET Devenu en 2009 l’Etat plurinational de Bolivie, ce et Nadine LUCAS petit pays andin (comparé à ses géants voisins) ENQUETE ET REDACTION compose l’un des panoramas les plus grandioses Arnaud BONNEFOY, Hervé FOISSOTTE, Pierre KAPSALIS, Fabrice PAWLAK, de l’Amérique latine : c’est un peu à la Bolivie Christian INCHAUSTE, Paola ERGUETA, qu’on rêve quand on se plonge dans l’imaginaire Klaus INCHAUSTE, Marcelo BORJA et Freddy ORTIZ des paysans charriant leur caravane de lamas, des STUDIO jungles inaccessibles, des petits villages perdus Sophie LECHERTIER et Romain AUDREN au bout du monde entre d’immenses montagnes MAQUETTE & MONTAGE Julie BORDES, Élodie CARY, Élodie CLAVIER, enneigées… La Bolivie, c’est l’Amérique latine, et un Sandrine MECKING, Delphine PAGANO, peu plus encore. A l’image du président Evo Morales Émilie PICARD et Laurie PILLOIS Ayma, le pays est indien (comprenez : indigène) et CARTOGRAPHIE Philippe PARAIRE, Thomas TISSIER fier de l’être. La difficile question de l’identité des Boliviens semble peu à peu trouver réponse dans PHOTOTHEQUE ✆ 01 72 69 08 07 Élodie SCHUCK et Sandrine LUCAS ce creuset, né de la coexistence dans la différence REGIE INTERNATIONALE ✆ 01 53 69 65 50 et du partage de valeurs communes qui pourrait Karine VIROT, Camille ESMIEU, Romain COLLYER, devenir un vrai modèle d’intégration. -

Crease La Sexta Seccion De La Provincia Ingavi Del Departamento De La Paz Con Su Capital Jesus De Machaka

CREASE LA SEXTA SECCION DE LA PROVINCIA INGAVI DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE LA PAZ CON SU CAPITAL JESUS DE MACHAKA. LEY N 2351 LEY DE 7 DE MAYO DE 2002 JORGE QUIROGA RAMIREZ PRESIDENTE CONSTITUCIONAL DE LA REPUBLICA Por cuanto, el Honorable Congreso Nacional, ha sancionado la siguiente ley: EL HONORABLE CONGRESO NACIONAL, DECRETA: ARTICULO 1°.- Créase la Sexta Sección de la Provincia Ingavi del Departamento de La Paz con su Capital Jesús de Machaka, conformada por los Cantones: 1. Jesús de Machaka, 2. Asunción de Machaka, 3. Aguallamaya (Awallamaya) 4. Calla (Qalla Tupa Katari), 5. Mejillones, 6. Qhunqhu, 7. Santo Domingo de Machaka, 8. Cuipa España (Kuypa de Machaka), 9. Santa Ana de Machaka, 10. Chama (Ch' ama). ARTICULO 2°.- Las colindancias de la Sexta Sección de Provincia son: al Norte, con la Segunda y Tercera Sección de la Provincia Ingavi; al Noreste con la Provincia Los Andes; al Este con la Primera Sección de la Provincia Ingavi y de la Provincia Pacajes; al Sur con la Provincia Pacajes y los cantones Nazacara (Nasa q'ara) Y San Andrés de Machaka de la Quinta Sección de la Provincia Ingavi; al Oeste con el Cantón Conchacollo (kuncha qullu) de la Quinta Sección de Provincia de la Provincia Ingavi y la Cuarta Sección de la Provincia Ingavi. ARTICULO 3°.- Los límites definidos con la identificación de puntos y coordenadas UTM, son los siguientes: ARTICULO 4°.- Apruébase los Anexos 1, referido al Mapa escala 1:250 000 y Anexo 2, referido a la descripción de límites, mismos que forman parte de la presente Ley. -

Apellido Paterno Apellido Materno Nombres Lugar De Origen Lugar De

Apellido Paterno Apellido Materno Nombres Lugar de origen Lugar de destino Sexo Abacay Flores Keila Pilar Santa Cruz Trinidad F Abalos Aban Jerson Sucre Tupiza M Aban Nur de Serrano Gabi Santa Cruz Sucre F Abecia NC Vicente Villazón Tarija M Abrego Camacho Francisco Javier Santa Cruz Puerto Suárez M Abrego Lazo Olga Cochabamba San Borja- Beni F Abularach Vásquez Elida Diana Cochabamba Riberalta F Abularach Vásquez Ericka Daniela Cochabamba Riberalta F Acahuana Paco Neymar Gael Santa Cruz La Paz M Acahuana Paco Mauro Matías Santa Cruz La Paz M Acarapi Higuera Esnayder Santa Cruz Cochabamba M Acarapi Galán Axel Alejandro Potosí Cochabamba M Acarapi Montan Noemi Oruro Cochabamba F Acarapi Leocadia Trinidad Cochabamba F Acebey Diaz Anahi Virginia La Paz Tupiza F Acebo Mezza Jorge Daniel Sucre Yacuiba M Achacollo Jorge Calixto Puerto Rico Oruro M Acho Quispe Carlos Javier Potosí La Paz M Achocalla Chura Bethy Santa Cruz La Paz F Achocalle Flores Santiago Santa Cruz Oruro M Achumiri Alave Pedro La Paz Trinidad M Acosta Guitierrez Wilson Cochabamba Bermejo- Tarija M Acosta Rojas Adela Cochabamba Guayaramerin F Acosta Avendaño Arnoldo Sucre Tarija M Acosta Avendaño Filmo Sucre Tarija M Acosta Vaca Francisco Cochabamba Guayaramerin M Acuña NC Pablo Andres Santa Cruz Camiri M Adrian Sayale Hernan Gualberto Cochabamba Oruro M Adrian Aurelia Trinidad Oruro F Adrián Calderón Israel Santa Cruz La Paz M Aduviri Zevallos Susana Challapata Sucre F Agreda Flores Camila Brenda Warnes Chulumani F Aguada Montero Mara Cochabamba Cobija F Aguada Montero Milenka -

“Estrategia De Desarrollo Turístico En Sorata”

UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN CARRERRA TURISMO PROYECTO DE GRADO “Estrategia de Desarrollo Turístico en Sorata” Nombre: Liliana Vanessa Flores Velarde Sara Suzan Torrez Cordova Tutor: Arq. Jorge Antonio Gutiérrez Adauto 2012 1 “Estrategia de Desarrollo Turístico en Sorata” AGRADECIMIENTO Agradecemos a nuestras familias, a la Dra. Gina Fuentes, al Arq. Yuri Rada quien nos dio una nueva visión de la actividad turística, al tutor que nos orientó y finalmente a las personas de Sorata e Ilabaya que nos brindaron información para la elaboración del presente proyecto. 2 “Estrategia de Desarrollo Turístico en Sorata” CONTENIDO Páginas CAPITULO I ANTECEDENTES GENERALES Acrónimos y Abreviaturas 1. Presentación 2 2. Resumen Ejecutivo 3 3. Antecedentes 5 4. Justificación 9 5. Marco Lógico 11 6. Objetivos 16 a. Objetivo General 16 b. Objetivos Específicos 16 7. Metodología 16 CAPÍTULO II MARCO REFERENCIAL 1. Marco Conceptual 22 a. Turismo 23 b. Tipos de turismo 24 a) Turismo alternativo 24 b) Turismo aventura 25 c) Turismo de naturaleza 25 d) Turismo religioso 26 1.3 Oferta turística 27 a) Producto turístico 28 b) Atractivos turísticos 31 c) Inventariación 31 d) Jerarquización 31 e) Circuito turístico 32 f) Medio Ambiente 33 g) Conservación 33 h) Servicios turísticos 34 i) Establecimientos de hospedaje 36 j) Agencias de viaje 36 k) Alimentación 37 l) Marketing 38 m) Promoción 39 n) Publicidad 39 1.4 Demanda turística 40 a) Demanda efectiva 41 b) Demanda potencial 41 1.5 Instituciones 41 a) institución Publica 42 b) Institución Privada 42 1.6 Planificación 42 3 “Estrategia de Desarrollo Turístico en Sorata” CONTENIDO Páginas 1.7 Estrategia 43 1.8 Programa 44 1.9 Proyecto 44 1.10 Manual 44 1.11 Capacitación 45 2. -

Floods –13 February 2008

Situation Report 8 – BOLIVIA – FLOODS –13 FEBRUARY 2008 This situation report is based on information received from the Office of the Resident Coordinator, UN Agencies, the Bolivian Government, the UN Emergency Technical Team (UNETT) in Bolivia and OCHA Regional Office in Panama. HIGHLIGHTS • The floods claimed 52 lives and affected more than 55, 649 families. The President of Bolivia Evo Morales declared a state of national disaster on 12 February. • A Flash Appeal will be prepared in view of the deterioration of the situation. SITUATION OVERVIEW According to the projections of SEMENA, water levels in the Trinidad region will continue to rise 1. Since November 2007, several parts of Bolivia during the next 4 days. At noon on February 12, the have been affected by floods and heavy rains. water level surpassed part of the protecting levees in According to the Vice Ministry of Civil Defense, the the South-East of Trinidad and partially flooded the disaster has claimed 52 lives and affected 55,649 city where thousands of persons had taken shelter. families. Eight persons are missing. On Tuesday Some 25% of the population of Trinidad has been February 12, the Government declared a state of affected i.e. 3, 546 families or an estimated 16,753 national disaster. Some 57 of the 327 municipalities persons. in the nine departments of Bolivia are in red alert. The declaration of national disaster allows the 3. Some 347 schools were damaged or destroyed authorities to immediately request 1% of the national affecting approximately 20,820 students and 694 budget to respond to the situation. -

Community Management of Wild Vicuña in Bolivia As a Relevant Case to Explore Community- Based Conservation Under Common Property Regimes, As Explained in Chapter 1

Community-based Conservation and Vicuña Management in the Bolivian Highlands by Nadine Renaudeau d’Arc Thesis submitted to the University of East Anglia for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2005 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. Abstract Abstract Current theory suggests that common property regimes, predicated on the community concept, are effective institutions for wildlife management. This thesis uses community-based conservation of vicuña in the Bolivian highlands as a case study to re-examine this theory. Vicuña is a wild South American camelid living in the high Andes. Its fibre is highly valued in international markets, and trade of vicuña fibre is controlled and regulated by an international policy framework. Different vicuña management systems have been developed to obtain fibre from live- shorn designated vicuña populations. This thesis analyses whether the Bolivian case study meets three key criteria for effective common property resource management: appropriate partnerships across scale exist; supportive local-level collective action institutions can be identified; and deriving meaningful benefits from conservation is possible. This thesis adopts a qualitative approach for the collection and analysis of empirical data. Data was collected from 2001 to 2003 at different levels of governance in Bolivia, using a combination of ethnographic techniques, and methods of triangulation. Community-level research was undertaken in Mauri-Desaguadero and Lipez-Chichas fieldwork sites. -

(Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú

Indice Diagnostico Ambiental del Sistema Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopo-Salar de Coipasa (Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú Indice Executive Summary in English UNEP - División de Aguas Continentales Programa de al Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente GOBIERNO DE BOLIVIA GOBIERNO DEL PERU Comité Ad-Hoc de Transición de la Autoridad Autónoma Binacional del Sistema TDPS Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente Departamento de Desarrollo Regional y Medio Ambiente Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos Washington, D.C., 1996 Paisaje del Lago Titicaca Fotografía de Newton V. Cordeiro Indice Prefacio Resumen ejecutivo http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (1 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Antecedentes y alcance Area del proyecto Aspectos climáticos e hidrológicos Uso del agua Contaminación del agua Desarrollo pesquero Relieve y erosión Suelos Desarrollo agrícola y pecuario Ecosistemas Desarrollo turístico Desarrollo minero e industrial Medio socioeconómico Marco jurídico y gestión institucional Propuesta de gestión ambiental Preparación del diagnóstico ambiental Executive summary Background and scope Project area Climate and hydrological features Water use Water pollution Fishery development Relief and erosion Soils Agricultural development Ecosystems Tourism development Mining and industrial development Socioeconomic environment Legal framework and institutional management Proposed approach to environmental management Preparation of the environmental assessment Introducción Antecedentes Objetivos Metodología Características generales del sistema TDPS http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (2 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Capítulo I. Descripción del medio natural 1. Clima 2. Geología y geomorfología 3. Capacidad de uso de los suelos 4. -

Plan De Desarrollo Municpal 2008-2012

PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL MUNICIPIO CALACOTO 2008 - 2012 i PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICPAL Calacoto 2008-2012 PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL MUNICIPIO CALACOTO 2008 - 2012 ii INDICE DE CONTENIDO A. ASPECTOS ESPACIALES ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 A.1 UBICACIÓN GEOGRÁFICA .............................................................................................................................................. 1 A.1.1 LAT ITUD Y LONGITUD ......................................................................................................................................... 1 A.1.2 LÍMITES TERRITORIALES ...................................................................................................................................... 1 A.1.3 EXTENSIÓN ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 A.2 DIVISIÓN POLÍTICA-ADMINISTRATIVA ....................................................................................................................... 2 A.2.1 DISTRITOS Y CANTONES. ...................................................................................................................................... 2 A.2.2 COMUNIDADES Y CENTROS POBLADOS. .......................................................................................................... 3 A.3 MANEJO ESPACIAL ..........................................................................................................................................................