Bolivia Rapid Response Floods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

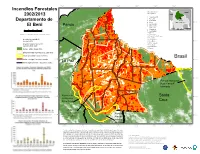

Incendios Forestales 2002/2013 Departamento De El Beni

68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 62°W Incendios Forestales municipalidades/ Brazil municipalities Peru 2002/2013 1 Guayaramerín 2 Riberalta 3 Santa Rosa El Beni Departamento de 11°S 4 Reyes B O L I V I A 11°S 5 San Joaquín Pando 6 Puerto Siles El Beni 1 7 Exaltacion Paraguay 0 25 50 75 100 2 8 Magdalena Chile Argentina Km 9 San Ramón 10 Baures escala 1/4.100.000,Lamber Conformal Conic 11 Huacaraje 12 Santa Ana de Yacuma 13 San Javier incendio forestal 2013/ 14 San Ignacio 12°S hot pixel 2013 15 San Borja 12°S 16 Rurrenabaque incendio forestal 2002-2012/ 17 Trinidad hot pixel 2002-2012 18 San Andrés 6 19 Loreto bosque 2005 / forest 2005 población indígena/indigenous settlement 7 areas protegidas / protected area 8 Brasil limite municipal / municipal border 13°S 5 13°S limite departamental / regional boundary La Paz 4 3 9 10 11 14°S 14°S 1 Parque Nacional Noel Kempff 12 13 Mercado 16 17 15°S Reserva de 15 Santa 15°S la Biosfera Pilon Lajas Cruz 14 19 18 Reserva de la Biosfera Parque 16°S 16°S del Beni Nacional Isiboro Secure 68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 62°W 61°W *Cada incendio forestal representa el punto central de un píxel 1km2 de MODIS, por lo que el incendio detectado se puede situar en cualquier lugar dentro del área de 1km2. Si el punto central del pixel (y por tanto el lugar del incendio reportado) está dentro del bosque, pero a menos de 500m de la frontera forestal, existe la posibilidad de que el incendio haya ocurrido realmente fuera del bosque a lo largo de Fuente de Datos: Cobertura Forestal ~1990~2005 (Conservation International) la frontera forestal. -

From “Invisible Natives” to an “Irruption of Indigenous Identity”? Two Decades of Change Among the Tacana in the Northern Bolivian Amazon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Sondra Wentzel provided by Institutional Repository of the Ibero-American Institute, Berlin From “invisible natives” to an “irruption of indigenous identity”? Two decades of change among the Tacana in the northern Bolivian Amazon “Al final nos dimos cuenta todos que éramos tacanas” (Tacana leader 2001, quoted in Herrera 2009: 1). 1. Introduction: The Tacana In the mid 1980s, a time of redemocratization and structural adjustment policies in Bolivia, consultations about a region suitable for field research on the situation of indigenous peoples in the context of “Amazonian development” led me to the Province of Iturralde in the lowland north of the Department of La Paz (Figure 1). The culture of its indigenous inhabitants, the Tacana,1 had been documented by German researchers in the early 1950s (Hissink & Hahn 1961; 1984). Also, under the motto La Marcha al Norte, the region was the focus of large infrastructure and agro industrial projects which had already stimulated spontaneous colonization, but local people had little information about these activities nor support to defend their rights and interests. Between 1985 and 1988, I conducted about a year of village level field re- search in the region, mainly in Tumupasa, an ex-Franciscan mission among the Tacana founded in 1713 and transferred to its current location around 1770, San- ta Ana, a mixed community founded in 1971, and 25 de Mayo, a highland colonist cooperative whose members had settled between Tumupasa and Santa Ana from 1979 1 Tacana branch of the Pano-Tacanan language family, whose other current members are the Araona, Cavineño, Ese Ejja, and Reyesano (Maropa). -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title Voluntary collective isolation as a best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations? A case study and protocol from the Bolivian Amazon. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99b288w4 Journal Lancet (London, England), 395(10238) ISSN 0140-6736 Authors Kaplan, Hillard S Trumble, Benjamin C Stieglitz, Jonathan et al. Publication Date 2020-05-15 DOI 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31104-1 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- 19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active. Public Health Voluntary collective isolation as a best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations? A case study and protocol from the Bolivian Amazon Hillard S Kaplan, Benjamin C Trumble, Jonathan Stieglitz, Roberta Mendez Mamany, Maguin Gutierrez Cayuba, Leonardina Maito Moye, Sarah Alami, Thomas Kraft, Raul Quispe Gutierrez, Juan Copajira Adrian, Randall C Thompson, Gregory S Thomas, David E Michalik, Daniel Eid Rodriguez, Michael D Gurven Indigenous communities worldwide share common features that make them especially vulnerable to the Lancet 2020; 395: 1727–34 complications of and mortality from COVID-19. -

Floods –13 February 2008

Situation Report 8 – BOLIVIA – FLOODS –13 FEBRUARY 2008 This situation report is based on information received from the Office of the Resident Coordinator, UN Agencies, the Bolivian Government, the UN Emergency Technical Team (UNETT) in Bolivia and OCHA Regional Office in Panama. HIGHLIGHTS • The floods claimed 52 lives and affected more than 55, 649 families. The President of Bolivia Evo Morales declared a state of national disaster on 12 February. • A Flash Appeal will be prepared in view of the deterioration of the situation. SITUATION OVERVIEW According to the projections of SEMENA, water levels in the Trinidad region will continue to rise 1. Since November 2007, several parts of Bolivia during the next 4 days. At noon on February 12, the have been affected by floods and heavy rains. water level surpassed part of the protecting levees in According to the Vice Ministry of Civil Defense, the the South-East of Trinidad and partially flooded the disaster has claimed 52 lives and affected 55,649 city where thousands of persons had taken shelter. families. Eight persons are missing. On Tuesday Some 25% of the population of Trinidad has been February 12, the Government declared a state of affected i.e. 3, 546 families or an estimated 16,753 national disaster. Some 57 of the 327 municipalities persons. in the nine departments of Bolivia are in red alert. The declaration of national disaster allows the 3. Some 347 schools were damaged or destroyed authorities to immediately request 1% of the national affecting approximately 20,820 students and 694 budget to respond to the situation. -

Madera River Infrasturcture Paper

DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION Effects of Energy and Transportation Projects on Soybean Expansion in the Madeira River Basin By: Maria del Carmen Vera-Diaz, John Reid, Britaldo Soares Filho, Robert Kaufmann and Leonardo Fleck Support provided by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and The United States Agency for International Development Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the United States Agency for International Development. We also thank Marcos Amend and Glenn Switkes for their valuable comments and Cecilia Ayala, Pablo Pacheco, Luis Fernando Figueroa, and Jorge Molina for their data collection support in Bolivia. Thanks to Susan Reid for her revision of the English text. The findings of this study are those of the authors only. 2 Acronyms ANAPO Asociación Nacional de Productores de Oleaginosas CNO Constructora Norberto Odebrecht FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FURNAS Furnas Centrais Elétricas S.A. IBAMA Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis IBGE Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IIRSA The Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America INEI Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (Peru) IPAM Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia ISA Instituto Socioambiental IRN International Rivers Network LEME LEME Engenharia NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration NCAR National Center for Atmospheric Research NCEP National Center for Environmental Modeling PCE Projetos -

Almost Ten Years Since Decentralization Laws in Bolivia: Status Quo Or Improvement for the Lowland Indigenous People? Evidences from the Tsimane’ Amerindians Of

Working Paper Series Almost ten years since decentralization laws in Bolivia: Status quo or improvement for the lowland indigenous people? Evidences from the Tsimane’ Amerindians of the Beni. Vincent Vadez/a/ & Victoria Reyes-García/a/ /a/ Sustainable International Development Program, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA Address correspondence to: Vincent Vadez (c/o Ricardo Godoy) Sustainable International Development Program MS 078 Heller School for Social Policy and Management Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Key words: local governance, decentralization law, Tsimane’ Amerindians, Bolivia. Decentralization among the Tsimane’ lowland Amerindians (Bolivia) Vadez & Reyes-García 2 Abstract Decentralization laws were passed in Bolivia in 1994 under the name of “Leyes de Descentralización Administrativa y Participación Popular”. Three hundred and eleven new municipalities were created upon application of these laws, which contributed to the redistribution of part of the state budget toward the regions and to the reduction of the predominant power of large municipalities. This process, however, kept apart large tracks of the population, specially indigenous people from the lowlands. There are few reports that document the effects of decentralization on lowland indigenous people. Here, we fill the gap using the Tsimane’ Amerindians from the Beni department of Bolivia as a case study. The goals of this research were twofold. First, we measured how decentralization laws affected Tsimane’ Amerindians. Second, we estimated the level of awareness of the Tsimane’ population toward “civic” issues related to the society, decentralization, and participation in development projects in the area. -

A Comparative Analysis of Two Tsimane ’ Territories in the Bolivian Lowlands

5 Indigenous Governance, Protected Areas and Decentralised Forestry: A Comparative Analysis of Two Tsimane ’ Territories in the Bolivian Lowlands Patrick Bottazzi1 Abstract The “territorial historicity” related to the Tsimane’ people living in the Boliv- ian lowlands is a complex process involving many governmental and non- governmental actors. The initiative of evangelist missionary organisations at the beginning of the 1990s led to the formal recognition of two Tsimane’ territories. While one territory was given a double status – Biosphere Reserve and indigenous territory – the other territory was put directly under the management of indigenous people. Elucidating the historical background of the process that led to the recognition and institutionalisation of the indig- enous territories enables us to understand that the constitution of an indig- enous political organisation remains a voluntary process justified above all by territorial strategies that have been mainly supported by foreign non- governmental organisations (NGOs). Thus, indigenous political leaders are currently struggling to take part in a more formal mechanism of territorial governance emerging from municipalities, governmental forestry services and forestry companies. Faced with the difficulty of reconciling the objec- tives related to conservation, development and democratisation, the differ- ent actors are using ethnic considerations to legitimise their positions. This leads to what we describe as “institutional segmentation”, a phenomenon that makes it difficult to set up a form of territorial planning capable of tak- ing into account the diversity of socio-ecological needs. We argue that the role of municipalities should be strengthened in order to better coordinate territorial management, following the diverse socio-ecological logics that exist in the area. -

Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey June 2007

Government of Bolivia Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey June 2007 Bolivia Coca Survey for 2006 PREFACE The evidence from the 2006 Bolivia Coca Survey sends mixed signals. Overall, there is an 8% increase in cultivation over 2005 for a total of 27,500 hectares. Dire forecasts have not been borne out. Nevertheless, there are warning signs that should be heeded. Under Bolivian law, 12,000 hectares may be grown for traditional consumption or other legal uses: this Survey shows that the limit was exceeded in the Yungas of La Paz where most of the cultivation usually takes place. At the same time there has been a dramatic (19%) increase in the Chapare region, including more than 2,300 hectares of coca being grown in national parks in the Tropics of Cochabamba – a threat to the precious eco-system of the Amazon forests. The good news from this same region is that the amount of land devoted to the cultivation of alternative crops – such as bananas, pineapple, and palm heart – now exceeds the area used to grow coca. There are signs of hope that licit crops can help liberate vulnerable communities from poverty. Nevertheless, the considerable increase in seizures and the displacement of drug production to areas outside the coca growing areas, as reported by the Bolivian drug control police, demonstrates the need for sustained drug law enforcement of the Bolivian Government. Bolivia’s drug policy is in the spotlight. The Government needs to reassure the world that its support for coca growers will not lead to an increase in cocaine production. -

Project Document

DEVELOPMENT BANK OF LATIN AMERICA (CAF) PROJECT DOCUMENT FOR A GRANT FROM THE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY TRUST FUND OF USD 10.1 MILLION TO THE MINISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER OF BOLIVIA FOR THE PROJECT AMAZON SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPE APPROACH IN THE NATIONAL SYSTEM OF PROTECTED AREAS AND STRATEGIC ECOSYSTEMS OF BOLIVIA (INTEGRATED PROJECT AS PART OF THE AMAZON SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPES 2 SFM IMPACT PROGRAM) Revised 19 April 2021 EQUIVALENT VALUE (Official exchange rate as at 2 March 2020; source: BCB) 6.86 bolivianos (BOB) = 1 US dollar (USD) FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ASL Amazon Sustainable Landscapes Pilot Program – Programa Piloto de Impacto Territorios Sostenibles Amazónicos (GEF-6) ASL2 Amazon Sustainable Landscapes Program, Phase II – Programa de Impacto Territorios Sostenibles Amazónicos, Fase II (GEF-7) BCB Banco Central de Bolivia – Central Bank of Bolivia BOB Bolivian, currency – Boliviano, moneda C Carbon – Carbono CO2 Carbon dioxide – dióxido de carbono CAF Development Bank of Latin America – Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina; Corporación Andina de Fomento CIPOAP Association of Indigenous Amazonian Peoples of Pando – Central Indígena de Pueblos Originarios Amazónicos de Pando CNAMIB National Confederation of Indigenous Women of Bolivia – Confederación Nacional de Mujeres Indígenas de Bolivia CO2 Carbon dioxide – Dióxido de carbono CBO/OCB community-based organisation – organización comunitaria de base DGBAP General Directorate of Biodiversity and Protected Areas – Dirección General -

Estado Productivo Del Municipio De Riberalta 2020

Estado Productivo del Municipio de Riberalta 2020 Tabla de Contenidos 1. Introducción ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Generalidades ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2. Infraestructura ................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Estructura Productiva ............................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Tendencias productivas ................................................................................................................ 4 2.1.1 PIB Municipal y sus componentes ........................................................................................... 4 2.1.2 Valor Bruto de Producción ....................................................................................................... 4 2.1.3 Sector agropecuario (producción, productos, empleo) ................................................... 4 2.1.4 Sector Manufacturero ............................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Comercio Exterior ........................................................................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Ventas fuera del municipio ..................................................................................................... -

Pre-Columbian Ring Ditch Construction and Land Use on a ‘Chocolate Forest Island’ in the Bolivian Amazon

JOURNAL OF QUATERNARY SCIENCE (2016) 31(4) 337–347 ISSN 0267-8179. DOI: 10.1002/jqs.2835 Pre-Columbian ring ditch construction and land use on a ‘chocolate forest island’ in the Bolivian Amazon 1 1 2 3 JOHN F. CARSON, * FRANCIS E. MAYLE, BRONWEN S. WHITNEY, JOSE IRIARTE and J. DANIEL SOTO4 1Centre for Past Climate Change and Department of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading RG6 6AB, UK 2Department of Geography, Northumbria University Newcastle, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK 3Department of Archaeology, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK 4Herbario del Oriente Boliviano, Museo de Historia Natural Noel Kempff Mercado, Universidad Autonoma Gabriel Rene Moreno, Santa Cruz, Bolivia Received 17 June 2015; Revised 9 December 2015; Accepted 16 December 2015 ABSTRACT: We present a palaeoecological investigation of pre-Columbian land use in the savanna ‘forest island’ landscape of the north-east Bolivian Amazon. A 5700-year sediment core from La Luna Lake, located adjacent to the La Luna forest island site, was analysed for fossil pollen and charcoal. We aimed to determine the palaeoenvironmental context of pre-Columbian occupation on the site and assess the environmental impact of land use in the forest island region. Evidence for anthropogenic burning and Zea mays L. cultivation began 2000 cal a BP, at a time when the island was covered by savanna, under drier-than-present climatic conditions. After 1240 cal a BP burning declined and afforestation occurred. We show that construction of the ring ditch, which encircles the island, did not involve substantial deforestation. Previous estimates of pre-Columbian population size in this region, based upon labour required for forest clearance, should therefore be reconsidered. -

Analysis of the Potential of IIRSA Projects for Production Integration and Development of Value-Added Logistics Services (Iprlg)

November 2009 Interoceanic Hub Application toGroup of Projects5– Central Services (IPrLg) Logistics Value-Added Production Integrationand Development of Projects for Analysis ofthePotentialIIRSA D E V R E S E R S T H G I R L L A - A S R I I www. iirsa .org D E V R E S E R S T H G I R L L A - A S R I I D E V R E S E R S T H G I R Analysis of the Potential for L L A Production Integration and - A Development of Value-Added Logistics S R I Services I Project Group 5 Central Interoceanic Hub November 2009 CENTRAL INTEROCEANIC HUB – PROJECT GROUP 5 ANALYSIS OF THE POTENTIAL FOR PRODUCTION INTEGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT OF VALUE-ADDED LOGISTICS SERVICES Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 List of the Persons Participating in the Application ......................................................... 4 Definitions ....................................................................................................................... 6 1. The Central Interoceanic Hub Project Group 5 Area of Influence ........................... 8 1.1 Current Status of the Projects in the Group ............................................... 8 1.2 Criteria Used to Delimit the Area of Influence .......................................... 10 1.3 The Area of Influence .............................................................................