A Comparative Analysis of Two Tsimane ’ Territories in the Bolivian Lowlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From “Invisible Natives” to an “Irruption of Indigenous Identity”? Two Decades of Change Among the Tacana in the Northern Bolivian Amazon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Sondra Wentzel provided by Institutional Repository of the Ibero-American Institute, Berlin From “invisible natives” to an “irruption of indigenous identity”? Two decades of change among the Tacana in the northern Bolivian Amazon “Al final nos dimos cuenta todos que éramos tacanas” (Tacana leader 2001, quoted in Herrera 2009: 1). 1. Introduction: The Tacana In the mid 1980s, a time of redemocratization and structural adjustment policies in Bolivia, consultations about a region suitable for field research on the situation of indigenous peoples in the context of “Amazonian development” led me to the Province of Iturralde in the lowland north of the Department of La Paz (Figure 1). The culture of its indigenous inhabitants, the Tacana,1 had been documented by German researchers in the early 1950s (Hissink & Hahn 1961; 1984). Also, under the motto La Marcha al Norte, the region was the focus of large infrastructure and agro industrial projects which had already stimulated spontaneous colonization, but local people had little information about these activities nor support to defend their rights and interests. Between 1985 and 1988, I conducted about a year of village level field re- search in the region, mainly in Tumupasa, an ex-Franciscan mission among the Tacana founded in 1713 and transferred to its current location around 1770, San- ta Ana, a mixed community founded in 1971, and 25 de Mayo, a highland colonist cooperative whose members had settled between Tumupasa and Santa Ana from 1979 1 Tacana branch of the Pano-Tacanan language family, whose other current members are the Araona, Cavineño, Ese Ejja, and Reyesano (Maropa). -

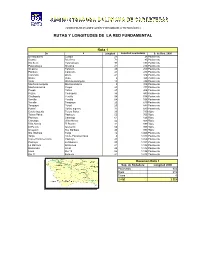

Rutas Y Longitudes De La Red Fundamental

GERENCIA DE PLANIFICACIÓN Y DESARROLLO TECNOLÓGICO RUTAS Y LONGITUDES DE LA RED FUNDAMENTAL Ruta 1 De A Longitud Longitud acumulada S. de Rod. 2006 Desaguadero Guaqui 24 24 Pavimento Guaqui Rio Seco 72 95 Pavimento Rio Seco Patacamaya 98 193 Pavimento Patacamaya Sicasica 21 214 Pavimento Sicasica Panduro 45 259 Pavimento Panduro Caracollo 24 283 Pavimento Caracollo Oruro 41 324 Pavimento Oruro Vinto 4 328 Pavimento Vinto Machacamarquita 18 346 Pavimento Machacamarquita Machacamarca 8 354 Pavimento Machacamarca Poopó 23 377 Pavimento Poopó Pazña 27 404 Pavimento Pazña Challapata 36 440 Pavimento Challapata Ventilla 94 534 Pavimento Ventilla Yocalla 64 598 Pavimento Yocalla Tarapaya 20 619 Pavimento Tarapaya Potosí 25 643 Pavimento Potosí Cuchu Ingenio 37 680 Pavimento Cuchu Ingenio Totora Palca 30 710 Ripio Totora Palca Padcoyo 55 765 Ripio Padcoyo Camargo 61 826 Ripio Camargo Villa Abecia 42 868 Ripio Villa Abecia El Puente 31 899 Ripio El Puente Iscayachi 54 953 Ripio Iscayachi Sta. Bárbara 40 993 Ripio Sta. Bárbara Tarija 12 1.005 Pavimento Tarija Cruce Panamericana 8 1.013 Pavimento Cruce Panamericana Padcaya 43 1.056 Pavimento Padcaya La Mamora 45 1.101 Pavimento La Mamora Emborozú 21 1.122 Pavimento Emborozú Limal 20 1.142 Pavimento Limal Km 19 52 1.194 Pavimento Km 19 Bermejo 21 1.215 Pavimento Resumen Ruta 1 Sup. de Rodadura Longitud 2006 Pavimento 902 Ripio 313 Tierra 0 Total 1.215 GERENCIA DE PLANIFICACIÓN Y DESARROLLO TECNOLÓGICO RUTAS Y LONGITUDES DE LA RED FUNDAMENTAL Ruta 2 De A Longitud Longitud acumulada S. de Rod. 2006 Kasani Copacabana 8 8 Pavimento Copacabana Tiquina 40 48 Pavimento Tiquina Huarina 37 85 Pavimento Huarina Río Seco 57 142 Pavimento El Alto La Paz 13 155 Pavimento Resumen Ruta 2 Sup. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title Voluntary collective isolation as a best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations? A case study and protocol from the Bolivian Amazon. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99b288w4 Journal Lancet (London, England), 395(10238) ISSN 0140-6736 Authors Kaplan, Hillard S Trumble, Benjamin C Stieglitz, Jonathan et al. Publication Date 2020-05-15 DOI 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31104-1 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- 19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active. Public Health Voluntary collective isolation as a best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations? A case study and protocol from the Bolivian Amazon Hillard S Kaplan, Benjamin C Trumble, Jonathan Stieglitz, Roberta Mendez Mamany, Maguin Gutierrez Cayuba, Leonardina Maito Moye, Sarah Alami, Thomas Kraft, Raul Quispe Gutierrez, Juan Copajira Adrian, Randall C Thompson, Gregory S Thomas, David E Michalik, Daniel Eid Rodriguez, Michael D Gurven Indigenous communities worldwide share common features that make them especially vulnerable to the Lancet 2020; 395: 1727–34 complications of and mortality from COVID-19. -

El Ceibo (Bolivia)

La Central de Cooperativas El Ceibo, la Política Nacional del Cacao y el Programa Nacional de Cacao Denominación Institucional El porqué del . Tomó este nombre por nombre? el árbol de nombre Ceibo (Erythrina poeppigiana) bastante común en la zona de producción. Es una Organización Cooperativa de Segundo grado que trabajan enmarcados bajo la Ley General de de Cooperativas de Bolivia. DATOS: Departamento de La Paz - Bolivia Provincias Caranavi, Sud Yungas y Larecaja, L.P. Ayopaya de Cbba. José Ballivián – Beni. A 270 km. de la ciudad de La Paz Temperatura promedio 25°C Precipitación media anual 1.800 mm Humedad relativa 70-80% Altitud 450m hasta 900m snm. DATOS GENERALES Aglutina a 48 cooperativas de base y 3 asociaciones (particulares) en 3 Municipios de La Paz (Palos Blancos, Teoponte y Alto Beni), 2 Municipios de Beni (Rurrenabaque y San Buenaventura) y Parte del Municipio de Ayopaya en Cochabamba. 1400 Productores de los cuales 1200 son socios y 200 particulares Certificamos aproximadamente 4.500 hectáreas de cacao. Un equipo técnico que evalua con mas de 30 selecciones locales de cacao, 6 son priorizadas. 4 7,000 6,000 Coch 5,000 Beni abam 9% ba 7% 4,000 Santa Cruz 3,000 1% 2,000 La 1,000 Pand o Paz 2% 81% 0 INE, 2016 5 Estimación de producción en grano seco en Alto Beni (Tn/año) 1600 1400 1380 1200 1391 1451 1415 1278 1233 1288 1000 1208 1182 1143 800 988 600 400 200 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Prod. CEIBO Producción TM Alto Beni 7 8 El 29 y 30 de noviembre del 2006 se realizó el 1er Congreso Nacional de Actores de la Cadena Productiva de Cacao de Bolivia, realizado en la localidad de Sapecho, del departamento de La Paz, a la cual asistieron 180 productores y recolectores de cacao. -

Datos De PTM 20200331

Tipo de PTM Nombre del Departamento Localidad Dirección Días de Atención Lunes a Viernes de PTM BOCA Punto Jhojoh Beni Guayaramerin Calle Cirio Simone No 512 Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Centro de Beni Guayaramerin Avenida Gral Federico Roman S/N Esquina Calle Cbba Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Centro de Beni Reyes Calle Comercio Entre Calle Gualberto Villarroel Y German Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM Central Jcell Beni Riberalta Avenida Dr Martinez S/N zona Central Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Centro De Beni Yucumo Calle Nelvy Caba S/N Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM ELISA - Beni Santa Rosa de C/Yacuma S/N EsqComercio Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Café Internet Beni Guayaramerin Calle Tarija S/N esquina Avenida Federico Roman Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Café Internet Mary Beni San Borja Avenida Cochabamba S/N esquina Avenida Selim Masluf Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Giros Mamoré Beni Trinidad Calle Teniente Luis Cespedez S/N esquina Calle Hnos. Rioja Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM Pulperia Tania Beni Riberalta Barrio 14 de Junio Avenida Aceitera esquina Pachuiba Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM Wester Union Beni Riberalta Av Chuquisaca No 713 Lado Linea Aerea Amazonas Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM Farmacia La Beni Trinidad Calle La Paz esquina Pedro de la Rocha Zona Central Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Reyna Rosario Beni Riberalta C/ Juan Aberdi Entre Av. -

Planificación Estratégica

Ministerio de Planificación del Desarrollo Viceministerio de Planificación y Coordinación PROPUESTA DE PRESENTACIÓN MODELO PARA LA ETAPA DE SOCIALIZACIÓN PLANIFICACIÓN ESTRATÉGICA Febrero, 2017 AGENDA PATRIÓTICA 2025 . La Agenda Patriótica 2025 promulgada según Ley No. 650 de fecha 15-01-2015, plantea 13 Pilares hacia la construcción de una Bolivia Digna y Soberana, con el objetivo de levantar una sociedad y un Estado más incluyente, participativo, democrático, sin discriminación, racismo, odio, ni división. Los 13 Pilares se constituyen en los cimientos y fundamentos principales del nuevo horizonte civilizatorio para el Vivir Bien. PLAN DE DESARROLLO ECONÓMICO Y SOCIAL: 2016 - 2020 1 5 9 Soberanía ambiental con Soberanía comunitaria Erradicación de la pobreza desarrollo integral y financiera sin servilismo al extrema respetando los derechos de capitalismo financiero la Madre Tierra DESARROLLO INTEGRAL HACIA EL VIVIR BIEN… VIVIR EL HACIA INTEGRAL DESARROLLO 2 6 10 Integración Socialización y Soberanía productiva con universalización de los diversificación y desarrollo complementaria de los servicios básicos con integral sin la dictadura del pueblos con soberanía PDES soberanía para Vivir Bien mercado capitalista 2016-2020 Disfrute y felicidad 12 3 Soberanía sobre nuestros 7 recursos naturales con plena de nuestras fiestas, Salud, educación y deporte nacionalización, de nuestra música, para la formación de un industrialización y nuestros ríos, nuestra ser humano integral comercialización en armonía selva, nuestras montañas, y equilibrio con la Madre nuestros nevados, de Tierra nuestro aire limpio, de nuestros sueños 8 4 13 AGENDA PATRIÓTICA: 2025 PATRIÓTICA: AGENDA Soberanía alimentaria a Soberanía científica y través de la construcción del Reencuentro soberano con CONSTITUCIÓN POLÍTICA DEL ESTADO DEL POLÍTICA CONSTITUCIÓN tecnológica con identidad Saber Alimentarse para Vivir nuestra alegría, felicidad, propia Bien prosperidad y nuestro mar. -

Madera River Infrasturcture Paper

DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION Effects of Energy and Transportation Projects on Soybean Expansion in the Madeira River Basin By: Maria del Carmen Vera-Diaz, John Reid, Britaldo Soares Filho, Robert Kaufmann and Leonardo Fleck Support provided by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and The United States Agency for International Development Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the United States Agency for International Development. We also thank Marcos Amend and Glenn Switkes for their valuable comments and Cecilia Ayala, Pablo Pacheco, Luis Fernando Figueroa, and Jorge Molina for their data collection support in Bolivia. Thanks to Susan Reid for her revision of the English text. The findings of this study are those of the authors only. 2 Acronyms ANAPO Asociación Nacional de Productores de Oleaginosas CNO Constructora Norberto Odebrecht FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FURNAS Furnas Centrais Elétricas S.A. IBAMA Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis IBGE Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IIRSA The Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America INEI Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (Peru) IPAM Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia ISA Instituto Socioambiental IRN International Rivers Network LEME LEME Engenharia NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration NCAR National Center for Atmospheric Research NCEP National Center for Environmental Modeling PCE Projetos -

Almost Ten Years Since Decentralization Laws in Bolivia: Status Quo Or Improvement for the Lowland Indigenous People? Evidences from the Tsimane’ Amerindians Of

Working Paper Series Almost ten years since decentralization laws in Bolivia: Status quo or improvement for the lowland indigenous people? Evidences from the Tsimane’ Amerindians of the Beni. Vincent Vadez/a/ & Victoria Reyes-García/a/ /a/ Sustainable International Development Program, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA Address correspondence to: Vincent Vadez (c/o Ricardo Godoy) Sustainable International Development Program MS 078 Heller School for Social Policy and Management Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02454-9110, USA E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Key words: local governance, decentralization law, Tsimane’ Amerindians, Bolivia. Decentralization among the Tsimane’ lowland Amerindians (Bolivia) Vadez & Reyes-García 2 Abstract Decentralization laws were passed in Bolivia in 1994 under the name of “Leyes de Descentralización Administrativa y Participación Popular”. Three hundred and eleven new municipalities were created upon application of these laws, which contributed to the redistribution of part of the state budget toward the regions and to the reduction of the predominant power of large municipalities. This process, however, kept apart large tracks of the population, specially indigenous people from the lowlands. There are few reports that document the effects of decentralization on lowland indigenous people. Here, we fill the gap using the Tsimane’ Amerindians from the Beni department of Bolivia as a case study. The goals of this research were twofold. First, we measured how decentralization laws affected Tsimane’ Amerindians. Second, we estimated the level of awareness of the Tsimane’ population toward “civic” issues related to the society, decentralization, and participation in development projects in the area. -

Download (2.95 MB )

“DUEÑAS DE NUESTRA VIDA, DUEÑAS DE NUESTRA TIERRA” Mujeres indígena originario campesinas y derecho a la tierra Pilar Uriona Crespo (Coordinadora de Investigación) Equipo de Investigación: Pelagio Pati Paco (Investigador responsable) Marina Patzy (Investigadora de apoyo) Jorge Loza (Investigador de apoyo) Coordinadora de la Mujer Dueñas de nuestra vida, dueñas de nuestra tierra. Mujeres indígena originario campesinas y derecho a la tierra / por Pilar Uriona Crespo (Coordinadora de Investigación), Pelagio Pati Paco (Investigador responsable), Marina Patzy (Investigadora de apoyo), Jorge Loza (Investigador de apoyo) La Paz, octubre de 2010, 146 p. Dueñas de nuestra VIDA, dueñas de nuestra TIERRA Mujeres indígena originario campesinas y derecho a la tierra Primera edición, octubre de 2010 Coordinadora de la Mujer Av. Arce Nº 2132, Edificio Illampu, piso 1, Of. “A” Telf./Fax: 244 49 22 – 244 49 23 – 244 4924 – 211 61 17 E-mail: [email protected] Página web: www.coordinadoramujer.org Casilla postal 9136 La Paz, Bolivia Depósito legal: 4-1-2413-10 ISBN: 978-99954-0-942-5 Cuidado de edición: Soraya Luján Diseño de tapas: Marcas Asociadas S.R.L. Diagramación: Alfredo Revollo Jaén Impresión: Impreso en Bolivia Printed in Bolivia ÍNDICE PresentacióN ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 I. sITUANDO EL DEBATE........................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Integrated Community Development Fund

NDO Integrated Community Development Fund Quarterly Report to USAID/Bolivia Integrated Alternative Development Office October - December 2009 Award Nº: 511-A-00-05-00153-00 December 2009 Contact: Treena Bishop Team Leader ICDF Calle 11 # 480 Esq. Sánchez Bustamante Calacoto La Paz, Bolivia Tel/Fax: (+591) 2 – 2793206 E-mail: [email protected] ACDI/VOCA is the implementer of the Integrated Community Development Fund, financed by USAID. __________________________________________________________________ La Paz Office: La Asunta Office : Palos Blancos Office: Coroico Office: Washington, DC Office: Calle 11 # 480 Esq. Sánchez Av. Oswaldo Natty s/n Esquina Plaza Principal Calle Tomás Manning 50 F Street NW , Suite 1075 Bustamante, Calacoto La Asunta – Sud Yungas Colonia Brecha Area 2 s/n frente Convento Washington, DC 20001 La Paz, Bolivia Cel.: 767-65965 Palos Blancos, Bolivia Madres Clarisas Tel: (202) 638-4661 Tel/Fax: (591-2) 279-3206 Tel/Fax: (2) 873-1613 – (2) Coroico - Bolivia http: www.acdivoca.org [email protected] 873-1614 Tel/Fax: (2) 289-5568 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 3 I. ICDF IN NUMBERS........................................................................................................... 7 II.1 Activities by Component and Region........................................................................... 14 II.2 Cross-cutting Activities ................................................................................................ -

Proyecto De Grado

UNIVERSISAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRES FACULTAD DE ARQUIECTURA ARTES DISEÑO Y URBANO CARRERA: ARQUITECTURA UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRES FACULTAD DE ARQUITECTURA, ARTES, DISEÑO Y URBANISMO CARRERA DE ARQUITECTURA PROYECTO DE GRADO “CABAÑAS SUSPENDIDAS TURÍSTICAS” SUD YUNGAS - CHULUMANI POSTULANTE.- ORTIZ DAZA DENISSE ALEJANDRA DOCENTES ASESORES.- ARQ. JORGE SAINZ CARDONA ARQ. BRISA SCHOLZ SANCHEZ LA PAZ – BOLIVIA GESTIÓN, 2018 1 UNIVERSISAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRES FACULTAD DE ARQUIECTURA ARTES DISEÑO Y URBANO CARRERA: ARQUITECTURA Dedicado A mis Padres y Hermana Luis Tito Ortiz Postigo, Karla Daza Rojas y Angela Ortiz Daza 2 UNIVERSISAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRES FACULTAD DE ARQUIECTURA ARTES DISEÑO Y URBANO CARRERA: ARQUITECTURA Agradecimientos especiales: Asesores del proyecto: Arq. Jorge Sainz Cardona Arq. Brisa Scholz Sanchez Y a la siguiente persona: Arq. German Sepúlveda 3 UNIVERSISAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRES FACULTAD DE ARQUIECTURA ARTES DISEÑO Y URBANO CARRERA: ARQUITECTURA INDICE CAPITULO I...................................................................................................................... 14 1.TITULO .......................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 Área temática ...................................................................................................... 14 2. DEFINICIÓN CONCEPTUAL DEL PROYECTO ........................................................... 14 2.1 Definición del título del proyecto genérico .......................................................... -

Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey June 2007

Government of Bolivia Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey June 2007 Bolivia Coca Survey for 2006 PREFACE The evidence from the 2006 Bolivia Coca Survey sends mixed signals. Overall, there is an 8% increase in cultivation over 2005 for a total of 27,500 hectares. Dire forecasts have not been borne out. Nevertheless, there are warning signs that should be heeded. Under Bolivian law, 12,000 hectares may be grown for traditional consumption or other legal uses: this Survey shows that the limit was exceeded in the Yungas of La Paz where most of the cultivation usually takes place. At the same time there has been a dramatic (19%) increase in the Chapare region, including more than 2,300 hectares of coca being grown in national parks in the Tropics of Cochabamba – a threat to the precious eco-system of the Amazon forests. The good news from this same region is that the amount of land devoted to the cultivation of alternative crops – such as bananas, pineapple, and palm heart – now exceeds the area used to grow coca. There are signs of hope that licit crops can help liberate vulnerable communities from poverty. Nevertheless, the considerable increase in seizures and the displacement of drug production to areas outside the coca growing areas, as reported by the Bolivian drug control police, demonstrates the need for sustained drug law enforcement of the Bolivian Government. Bolivia’s drug policy is in the spotlight. The Government needs to reassure the world that its support for coca growers will not lead to an increase in cocaine production.