Of Price Discriminiation, Rootkits and Flatrates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Disclosure Mechanism for Technological Protection Measures in China

Journal of Intellectual Property Rights Vol 17, November 2012, pp 532-538 Information Disclosure Mechanism for Technological Protection Measures in China Lili Zhao† Center for China Information Security Law, Xi’an Jiao tong University, Shaanxi Xi’an, P R China 710 049 Received 12 February 2012, revised 21 May 2012 With increasing cases of digital works being copied and pirated, technological protection measures have been greatly favoured by copyright owners for protecting the intellectual property in their digital works, while ensuring that these works can be used and disseminated. However, when any copyright owner or supplier fails to disclose the information of technological protection measures appropriately or effectively, damages such as privacy violations, security breaches and unfair competition may be caused to the public. Therefore, it is necessary to establish an information disclosure mechanism for technological protection measures, make the labeling obligation with regard to technological protection measures by copyright owners apparent and warning to security risks obligatory by legislation; effectively guarding against information security threats from the technological protection measures. Keywords: Technological protection measures, TPM, information disclosure, label and warning The advance of digital technologies make many information security, it is necessary to integrate such acts things become possible, including the copy and in a standardized, normalized and legal manner. dissemination of commercially valuable digital works Therefore, to further prevent copyright owners from through global digital network. Particularly, among using insecure or untested software, protect information the copyright owners of entertainment industry, security and prohibit the abuse of TPMs; disclosure technological protection measures (TPMs) have been obligations should be established for the right holders of regarded as a necessary creation to help digital works TPMs in the form of legislation. -

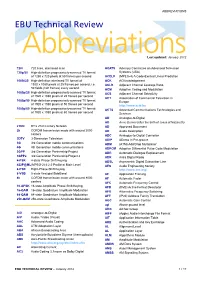

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

Intellectual Property Part 2 Pornography

Intellectual Property Part 2 Pornography By Jeremy Parmenter What is pornography Pornography is the explicit portrayal of sexual subject matter Can be found as books, magazines, videos The web has images, tube sites, and pay sites scattered with porn Statistics 12% of total websites are pornography websites 25% of total daily search engine requests are pornographic requests 42.7% of internet users who view pornography 34% internet users receive unwanted exposure to sexual material $4.9 billion in internet pornography sales 11 years old is the average age of first internet exposure to pornography Innovations ● Richard Gordon created an e-commerce start up in mid- 90s that was used on many sites, most notably selling Pamela Anderson/Tommey Lee sex tape ● Danni Ashe founded Danni's Hard Drive with one of the first streaming video without requiring a plug-in ● Adult content sites were one of the first to use traffic optimization by linking to similar sites ● Live chat during the early days of the web ● Pornographic companies were known to give away broadband devices to promote faster connections Negative Impacts ● Between 2001-2002 adult-oriented spam rose 450% ● Malware such as Trojans and video codecs occur most often on porn sites ● Domain hijacking, using fake documents and information to steal a site ● Pop-ups preventing users from leaving the site or infecting their computer ● Browser hijacking adware or spyware manipulating the browser to change home page or search engine to a bogus site, including pay-per-click adult site ● Accessibility -

The High-Definition Multimedia Interface

technology High-Defi nition Multimedia Interface It’s the interconnect that sorts out a lot of problems we thought we had and a few that we didn’t; it’s the High-Defi nition Multimedia Interface. NIGEL JOPSON discovers a new digital connector that has all sorts of implications for the future — including the forced deactivation of analogue outputs. just 15% of new sets sold this year will include it and be able to deliver the full 1080 high resolution picture that these devices are being sold on. Unlike the disparate disc formats that have polarised manufacturers into two camps, the HDMI connector has cross-industry support. The founders include electronics manufacturers Hitachi, Matsushita Electric (Panasonic), Philips, Sony, Thomson (RCA), Toshiba, and Silicon Image. Digital Content Protection LLC (a subsidiary of Intel) is providing High-bandwidth Digital Content Protection (HDCP) for HDMI. In addition, HDMI has the very partisan support of major movie producers Fox, Universal, Warner Bros and Disney, and system operators DirecTV and EchoStar (Dish Network) as well as CableLabs and Samsung. So HDMI is an industry-supported, uncompressed, all-digital audio/video interface. The small connector provides the interface between any compatible digital audio/video source, such as a set-top box, DVD player or AV receiver and a compatible digital audio and/or video monitor. It was conceived as a sort of digital SCART, primarily a point-to-point connector; HDMI grew out of DVI and the picture side is backwards compatible (providing that copy protection is implemented). HDMI adds support for component video, multichannel audio, the so-called universal CD control, and the concept of auto-confi guration. -

Is the Idea of Fair Digital Rights Management an Oxymoron? The

Royal Holloway Series Fair Digital Rights Management Fair digital rights management HOME THE BIRTH OF DIGITAL RIGHTS Is the idea of fair digital rights management an oxymoron? The MANAGEMENT music industry has been turned upside down by the Internet, and UNFAIR DIGITAL RIGHTS has tried various methods to protect its profits. But many of its MANAGEMENT actions have been either futile or heavy-handed. Christian Bonnici A DIGITAL RIGHTS and Keith Martin examine various approaches to see which would DILEMMA be most effective and fair to all parties. A COMPROMISE SOLUTION CONCLUSION REFERENCES 1 Royal Holloway Series Fair Digital Rights Management HERE ARE FEW issues more provocative than that THE BIRTH OF DIGITAL of the management of rights to digital content. RIGHTS MANAGEMENT For some consumers the internet is seen as an We will frame our discussion around music HOME Tagent of digital freedom, facilitating free and media, which is one of the most high profile types THE BIRTH OF easy access to digital content such as music and of digital content. FIGURE 1 (page 3) shows a sim - DIGITAL RIGHTS films. For some digital content providers the ple timeline indicating some of the milestones in MANAGEMENT internet has been seen as a technology that has the development of music media. The publication UNFAIR damaged their ability to earn money from selling of the MP3 music compression algorithm in 1991 DIGITAL RIGHTS their products. represents the most significant development with MANAGEMENT The solution to providers’ fears has been vari - respect to digital rights to music media, and this A DIGITAL ous attempts to control access to digital content event is pivotal to our discussion. -

Information Doesn't Want to Be Free Cory Doctorow

Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free Laws for the Internet Age Cory Doctorow Copyright © 2014 Cory Doctorow Cover design by Sunra Thompson. All rights reserved, including right of reproduction in whole or in part, in any form. McSweeney’s and colophon are registered trademarks of McSweeney’s, a privately held company with wildly fluctuating resources. Printed by Thomson-Shore in Michigan. ISBN 978-1-940450-28-5 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 www.mcsweeneys.net v FOREWORDS Neil Gaiman viii Amanda Palmer xii 0. INTRODUCTION Detente xviii 0.1 What Makes Money? xx 0.2 Don’t Quit Your Day Job—Really xxii 1. DOCTOROW’S FIRST LAW Any Time Someone Puts a Lock on Something That Belongs to You and Won’t Give You the Key, That Lock Isn’t There for Your Benefit 1 1.1 Anti-Circumvention Explained 4 1.2 Is This Copyright Protection? 7 1.3 So Is This Copy Protection? 12 1.4 Digital Locks Always Break 14 1.5 Understanding General-Purpose Computers 21 1.6 Rootkits Everywhere 23 1.7 Appliances 26 1.8 Proto-Appliances: The Inkjet Wars 28 1.9 Worse Than Nothing 31 2. DOCTOROW’S SECOND LAW Fame Won’t Make You Rich, But You Can’t Get Paid Without It 37 2.1 Good at Spreading Copies, Good at Spreading Fame 41 2.2 An Audience Machine 43 2.3 Getting People to Care About Your Work 49 2.4 Content Isn’t King 51 2.5 How Do I Get People to Pay Me? 53 2.6 Does This Mean You Should Ditch Your Investor and Go Indie? 64 2.7 Love 66 2.8 The New Intermediaries 69 2.9 Intermediary Liability 75 2.10 Notice and Takedown 77 2.11 So What’s Next? 80 2.12 More Intermediary Liability, Fewer Checks and Balances 82 2.13 Disorganized Channels Are Good for Creators 87 2.14 Freedom Can Be Expensive, but Censorship Costs Us the World 90 vi FOREWORDS 3. -

The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind

37278_u00.qxd 8/28/08 11:04 AM Page i The Public Domain ___-1 ___0 ___ 1 37278_u00.qxd 8/28/08 11:04 AM Page ii Thomas Jefferson to Isaac McPherson, August 13, 1813, p. 6. -1 ___ 0 ___ 1 ___ 37278_u00.qxd 8/28/08 11:04 AM Page iii James Boyle The Public Domain Enclosing the Commons of the Mind Yale University Press ___-1 New Haven & London ___0 ___ 1 37278_u00.qxd 8/28/08 11:04 AM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. Copyright © 2008 by James Boyle. All rights reserved. The author has made an online version of this work available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. It can be accessed through the author’s website at http://james-boyle.com. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 978-0-300-13740-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008932282 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). It contains 30 percent postconsumer waste (PCW) and is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) -1 ___ 0 ___ 1 ___ 37278_u00.qxd 8/28/08 11:04 AM Page v Contents Acknowledgments, vii Preface: Comprised of at Least Jelly?, xi 1 Why Intellectual Property?, 1 2 Thomas Jefferson Writes a Letter, 17 3 The Second Enclosure Movement, 42 4 The Internet Threat, 54 5 The Farmers’ Tale: An Allegory, 83 6 I Got a Mashup, 122 7 The Enclosure of Science and Technology: Two Case Studies, 160 8 A Creative Commons, 179 9 An Evidence-Free Zone, 205 10 An Environmentalism for Information, 230 ___-1 Notes and Further Readings, 249 ___0 Index, 297 ___ 1 v 37278_u00.qxd 8/28/08 11:04 AM Page vi -1 ___ 0 ___ 1 ___ 37278_u00.qxd 8/28/08 11:04 AM Page vii Acknowledgments The ideas for this book come from the theoretical and practical work I have been doing for the last ten years. -

Abkürzungs-Liste ABKLEX

Abkürzungs-Liste ABKLEX (Informatik, Telekommunikation) W. Alex 1. Juli 2021 Karlsruhe Copyright W. Alex, Karlsruhe, 1994 – 2018. Die Liste darf unentgeltlich benutzt und weitergegeben werden. The list may be used or copied free of any charge. Original Point of Distribution: http://www.abklex.de/abklex/ An authorized Czechian version is published on: http://www.sochorek.cz/archiv/slovniky/abklex.htm Author’s Email address: [email protected] 2 Kapitel 1 Abkürzungen Gehen wir von 30 Zeichen aus, aus denen Abkürzungen gebildet werden, und nehmen wir eine größte Länge von 5 Zeichen an, so lassen sich 25.137.930 verschiedene Abkür- zungen bilden (Kombinationen mit Wiederholung und Berücksichtigung der Reihenfol- ge). Es folgt eine Auswahl von rund 16000 Abkürzungen aus den Bereichen Informatik und Telekommunikation. Die Abkürzungen werden hier durchgehend groß geschrieben, Akzente, Bindestriche und dergleichen wurden weggelassen. Einige Abkürzungen sind geschützte Namen; diese sind nicht gekennzeichnet. Die Liste beschreibt nur den Ge- brauch, sie legt nicht eine Definition fest. 100GE 100 GBit/s Ethernet 16CIF 16 times Common Intermediate Format (Picture Format) 16QAM 16-state Quadrature Amplitude Modulation 1GFC 1 Gigabaud Fiber Channel (2, 4, 8, 10, 20GFC) 1GL 1st Generation Language (Maschinencode) 1TBS One True Brace Style (C) 1TR6 (ISDN-Protokoll D-Kanal, national) 247 24/7: 24 hours per day, 7 days per week 2D 2-dimensional 2FA Zwei-Faktor-Authentifizierung 2GL 2nd Generation Language (Assembler) 2L8 Too Late (Slang) 2MS Strukturierte -

SONY BMG Music Entertainment. Respondent. This Assurance Of

In the Matter of: SONY BMG Music Entertainment. Respondent. This Assuranceof Voluntary Complianceor Discontinuance('oAssurance") is enteredinto by the AttorneysGeneral of the Statesof Alabama,Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas,Connecticut, Delawareo Florida,Idatro,Illinois, Indiana,Iow4 Kentucky,Louisian4 Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan,Mississippi, Montana" Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey,New Mexico,New york, North Carolina,North Dakota,Ohio, Oklahoma,Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota,Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Washington,West Virginia, Wisconsin,and Wyoming, and by the Attorney Generalfor the District of Columbia("the States"),acting pursuantto their respectiveconsumet protection statutes,r and SONY BMG Music Entertainment(.SONy I ALABAMA: AlabamaDeceptive Trade Practices Act, Ala. Codeg 8-19-1,et seq.;ALASKA: Unfair TradePractices and Consumer Protection Act, AS 45.50.471,-etseq.;ARIZbNA: Arizonaconsumer lrf{191, A.R.s. $ 44-1521et seq.;ARKANSAS: Ark. stat.Ann., g 4-gg- l0l et seq.;COIYNECTICUT: Conn.Gen. Stat. $ 42-110a,et seq.; DELAWARE: Consumer FraudAct,6 Del.C.$251l, et seq.;DISTRICT OF COLUMBI* Districrof Columbia ConsumerProtection Procedures Act, D.C. Code$ 28-3901et seq.; FLORIDA: Deceptiveand Unfair TradePractices Act, Fla. Stat.Ch. 501.201et seq.;IDAHO: IdahoConsumer protection Act, IdahoCode $ 48-601,et seq.;ILLINOIS: ConsumerFraud and Deceptive Business PracticesAct, 815ILcs 505/l et seq.;INDIANA: Ind.code Ann. $24-5-b-5-l;IowA: Iowa ConsumerFraud Act, Iowa Codesection714.16; KENTUCKY: ConsumerProtection Act, Ky. Rev. Stat.$$ 367.1l0 to 367.990;LOUISIANA: Unfair Tradepractices and Consumer ProtectionLaw,La. Rev. Stat.Ann. $$51:1401to 5|:1420;MAINE: MaineUnfair Trade PracticesAct, 5 M.R.S.A.sections 207 and209;MARYLANDI MarylandConsumer protection Act, Md. -

The European IP Bulletin

The European IP Bulletin The Intellectual Property, Media & Technology Department Issue 28, January 2006 McDermott Will & Emery UK LLP 7 Bishopsgate London EC2N 3AR Tel: +44 20 7577 6900 Fax: +44 20 7577 6950 www.mwe.com www.mwe.com/london Boston Brussels Chicago Düsseldorf London Los Angeles Miami Munich New York Orange County Rome San Diego Silicon Valley Washington, D.C. SUMMARY OF PAGE CONTENTS NO. HOT TOPICS 1. WORLD TRADE ORGANISATION MEMBERS AGREE TO AMEND THE 1 TRIPS AGREEMENT ON PATENTS AND PUBLIC HEALTH The decision of the General Council of 6 December 2005 on the amendment of the TRIPS Agreement makes the flexibilities contained in the 2003 decision on patents and public health permanent. This in effect will lead to the first amendment of a core WTO Agreement. 2. UK CHANCELLOR ANNOUNCES INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY REVIEW 2 As part of his Pre-Budget Report Package, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, has announced the launch of an independent review of intellectual property in the UK, to be headed by the former editor of the Financial Times. COPYRIGHT 3. SONY BMG’S ANTI-PIRACY SOFTWARE IN BIG TROUBLE 3 Sony BMG’s trouble started immediately following Windows programming expert Mark Russinovich's discovery that Sony’s anti- piracy software used virus-like techniques to stop illegal copies being made. There have been several class action lawsuits launched against both Sony BMG and First4Internet. Widespread pressure has made Sony BMG take actions to settle the dispute. 4. EVALUATION OF EU RULES ON DATABASES 4 The European Commission has published an evaluation of the protection EU law gives to databases. -

Hackere / Crackere

UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Institutt for informatikk Hackere / Crackere Masteroppgave (60 studiepoeng) Ørjan Nordvik 1. februar 2006 Sammendrag Denne masteroppgaven går kort sagt ut på å finne ut hva som karakteriserer hackere og crackere. Det er viktig å klargjøre så tidlig som mulig i oppgaven hvordan jeg tolker disse to termene. I kapittel tre vil jeg gå grundig igjennom dette, men først vil jeg her kort oppsummere hvordan jeg kommer til å bruke begrepene hacker og cracker. Hackere er dataeksperter som holder seg på den riktige siden av loven, mens crackere er de som bryter loven. For å kunne diskutere de sentrale begrepene har jeg gjort en litteraturstudie som resulterte i kapittel tre, samt en empirisk undersøkelse ved å intervjue dataeksperter, hackere og crackere. Det er den empiriske undersøkelsen som består av en rekke kvalitative intervjuer, og data fra sekundærlitteraturen som danner datagrunnlaget i denne oppgaven. Hackere og crackere er etter min mening ikke homogene grupper som lett lar seg beskrive med få setninger. Det finnes et utall av motiver som ligger bak deres handlinger enten de er hacker eller cracker. Måten de arbeider på avhenger ofte av hvilket ferdighetsnivå de har. Det klassiske bilde av hackere som kvisete, coladrikkende fjortisser med tykke briller er en myte. Hackere og crackere finnes i alle samfunnslag og er like gjerne 30 som 15 år. Forord Denne masteroppgaven inngår som en del av mastergraden min ved Institutt for Informatikk, Universitetet i Oslo våren 2006. Området for forskningen er innen Informasjonssystemer oppgaven fokuserer på karakteristikker av hackere og crackere. Oppgaven er av «lang» type og gir 60 studiepoeng. -

DRM — “Digital Rights” Or “Digital Restrictions” Management?

DIGITAL RIGHTS MANAGEMENT DRM — “digital rights” or “digital restrictions” management? Richard Leeming Red Bee Media If correctly applied, DRM can be likened to a motorway, providing a seamless high- speed route to content, enabling people to get the content they want, where they want it, quickly and easily. However, if badly applied, heavy handed and overly restrictive, DRM is more like a traffic jam – denying people access to the content they want and crucially denying rights-holders the revenue they want. This article looks at some of the proprietary DRM systems currently available and argues that we need to start thinking hard about when and how we apply DRM to our precious content. In 2006, music lovers worldwide have been celebrating the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth. Although he only lived for 35 years, Mozart composed more than 600 pieces of classical music – most of which are still hugely popular today. But it’s perhaps something of a surprise to discover that one of the key moments of Mozart’s early career would today count as piracy and be prevented by digital-rights technology. As a 14-year-old, Mozart travelled to the Vatican and heard Gregorio Allegri’s Miserere. This piece of music had long been closely guarded by the Vatican and it was forbidden to transcribe it: if you did, you would be excommunicated. Whether Mozart knew this is unknown but, having heard it once, he transcribed it from memory and it became published in London, thus breaking the Vatican’s ban. This is perhaps one of the earliest-known examples of content rights management being overturned.