Contemplating a Digital First-Sale Doctrine Damien A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intellectual Property Protection Under the TRIPS Component of the WTO Agreement

J.H. REICHMAN* Universal Minimum Standards of Intellectual Property Protection under the TRIPS Component of the WTO Agreement I. Preliminary Considerations The absorption of classical intellectual property law into international economic law will gradually establish universal minimum standards' governing the relations between innovators and second comers in an integrated world market.2 This author's previous articles focused on the broader legal and economic implications of this trend.3 The object here is to convey a more detailed and comprehensive *B.A., Chicago, 1958; J.D., Yale, 1979. Professor of law, Vanderbilt Law School, Nashville, Tennessee. The author wishes to thank Rochelle Cooper Dreyfuss, Paul Edward Geller, Paul Goldstein, Robert E. Hudec, and David Nimmer for helpful comments and critical suggestions, John Henderson and Jon Mellis for their research assistance, and Dean John J. Costonis for the grants that supported this project. 1. For a perceptive analysis of the conditions favoring the growth of universal legal standards generally, see Jonathan I. Charney, Universal International Law, 87 AM. J. INT'L L. 529, 543-50 (1993) (stressing "central role" of multilateral forums "in the creation and shaping of contemporary international law" and the ability of these forums to "move the solutions substantially towards acquiring the status of international law"). 2. See, e.g., J.H. Reichman, The TRIPS Componentof the GATT 's Uruguay Round: Competitive Prospectsfor Intellectual Property Owners in an Integrated World Market, 4 FORDHAM INTELL. PROP., MEDIA & ENT. L.J. 171, 173-78, 254-66 (1993) [hereinafter Reichman, TRIPS Component]. For background to these negotiations, see also J.H. -

Information Disclosure Mechanism for Technological Protection Measures in China

Journal of Intellectual Property Rights Vol 17, November 2012, pp 532-538 Information Disclosure Mechanism for Technological Protection Measures in China Lili Zhao† Center for China Information Security Law, Xi’an Jiao tong University, Shaanxi Xi’an, P R China 710 049 Received 12 February 2012, revised 21 May 2012 With increasing cases of digital works being copied and pirated, technological protection measures have been greatly favoured by copyright owners for protecting the intellectual property in their digital works, while ensuring that these works can be used and disseminated. However, when any copyright owner or supplier fails to disclose the information of technological protection measures appropriately or effectively, damages such as privacy violations, security breaches and unfair competition may be caused to the public. Therefore, it is necessary to establish an information disclosure mechanism for technological protection measures, make the labeling obligation with regard to technological protection measures by copyright owners apparent and warning to security risks obligatory by legislation; effectively guarding against information security threats from the technological protection measures. Keywords: Technological protection measures, TPM, information disclosure, label and warning The advance of digital technologies make many information security, it is necessary to integrate such acts things become possible, including the copy and in a standardized, normalized and legal manner. dissemination of commercially valuable digital works Therefore, to further prevent copyright owners from through global digital network. Particularly, among using insecure or untested software, protect information the copyright owners of entertainment industry, security and prohibit the abuse of TPMs; disclosure technological protection measures (TPMs) have been obligations should be established for the right holders of regarded as a necessary creation to help digital works TPMs in the form of legislation. -

ELDRED V. ASHCROFT: the CONSTITUTIONALITY of the COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION ACT by Michaeljones

COPYRIGHT ELDRED V. ASHCROFT: THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION ACT By MichaelJones On January 15, 2003, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Copyright Term Extension Act ("CTEA"), which extended the term of copyright protection by twenty years.2 The decision has been ap- plauded by copyright protectionists who regard the extension as an effec- tive incentive to creators. In their view, it is a perfectly rational piece of legislation that reflects Congress's judgment as to the proper copyright term, balances the interests of copyright holders and users, and brings the3 United States into line with the European Union's copyright regime. However, the CTEA has been deplored by champions of a robust public domain, who see the extension as a giveaway to powerful conglomerates, which runs contrary to the public interest.4 Such activists see the CTEA as, in the words of Justice Stevens, a "gratuitous transfer of wealth" that will impoverish the public domain. 5 Consequently, Eldred, for those in agree- ment with Justice Stevens, is nothing less than the "Dred Scott case for 6 culture." The Court in Eldred rejected the petitioners' claims that (1) the CTEA did not pass constitutional muster under the Copyright Clause's "limited © 2004 Berkeley Technology Law Journal & Berkeley Center for Law and Technology. 1. Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, 17 U.S.C. §§ 108, 203, 301-304 (2002). The Act's four provisions consider term extensions, transfer rights, a new in- fringement exception, and the division of fees, respectively; this Note deals only with the first provision, that of term extensions. -

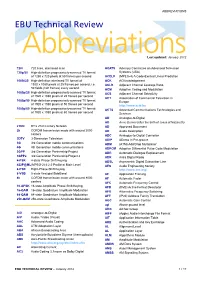

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

Intellectual Property Part 2 Pornography

Intellectual Property Part 2 Pornography By Jeremy Parmenter What is pornography Pornography is the explicit portrayal of sexual subject matter Can be found as books, magazines, videos The web has images, tube sites, and pay sites scattered with porn Statistics 12% of total websites are pornography websites 25% of total daily search engine requests are pornographic requests 42.7% of internet users who view pornography 34% internet users receive unwanted exposure to sexual material $4.9 billion in internet pornography sales 11 years old is the average age of first internet exposure to pornography Innovations ● Richard Gordon created an e-commerce start up in mid- 90s that was used on many sites, most notably selling Pamela Anderson/Tommey Lee sex tape ● Danni Ashe founded Danni's Hard Drive with one of the first streaming video without requiring a plug-in ● Adult content sites were one of the first to use traffic optimization by linking to similar sites ● Live chat during the early days of the web ● Pornographic companies were known to give away broadband devices to promote faster connections Negative Impacts ● Between 2001-2002 adult-oriented spam rose 450% ● Malware such as Trojans and video codecs occur most often on porn sites ● Domain hijacking, using fake documents and information to steal a site ● Pop-ups preventing users from leaving the site or infecting their computer ● Browser hijacking adware or spyware manipulating the browser to change home page or search engine to a bogus site, including pay-per-click adult site ● Accessibility -

A Case for a Longer Term of Copyright in Canada - Implications of Eldred V

COMMENTAIRE A CASE FOR A LONGER TERM OF COPYRIGHT IN CANADA - IMPLICATIONS OF ELDRED V. ASHCROFT par Kamil Gérard AHMED* En 1993, une directive de l'Union européenne a obligé les États membres à prolonger dans leur droit interne la durée minimale du droit d'auteur de vingt ans, la portant ainsi à soixante-dix ans après le décès de l'auteur, et exclut cette prolongation ne s=appliquant pas aux États non membres qui n=offrent pas la même durée de protection. Cette directive a été le fer de lance de changements législatifs à l'échelle internationale. En 1998, le Congrès américain a adopté le Copyright Term Extension Act, qui prolonge de vingt ans la durée de la protection des droits d'auteur existants et futurs. En 2003, l'arrêt de la Cour suprême des États-Unis Eldred c. Ashcroft, a confirmé la légalité du Copyright Term Extension Act. La protection couvrant la vie de l'auteur et les soixante-dix années suivant son décès dans l'Union européenne et aux États-Unis a eu des répercussions au Canada, où le régime de protection dans la Loi sur le droit d'auteur couvre à ce jour la durée de vie de l=auteur plus cinquante ans. Le présent exposé soutient la position que le Parlement canadien ne doit pas ignorer les développements à l'égard du droit d'auteur dans l'Union européenne et aux États-Unis et qu'il devrait modifier la Loi sur le droit d'auteur du Canada afin de prolonger la durée du droit d'auteur à soixante-dix ans après le décès de celui-ci. -

The Orrin Hatch – Bob Goodlatte Music Modernization Act

The Orrin Hatch – Bob Goodlatte Music Modernization Act A Guide for Sound Recordings Collectors This study was written by Eric Harbeson, on behalf of and commissioned by the National Recording Preservation Board. Members of the National Recording Preservation Board American Federation of Musicians National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences Billy Linneman Maureen Droney Alternate: Daryl Friedman American Folklore Society Burt Feintuch (in memoriam) National Archives and Records Administration Alternate: Timothy Lloyd Daniel Rooney Alternate: Tom Nastick American Musicological Society Judy Tsou Recording Industry Association of America Alternate: Patrick Warfield David Hughes Alternate: Patrick Kraus American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers SESAC Elizabeth Matthews John JosePhson Alternate: John Titta Alternate: Eric Lense Association for Recorded Sound Collections Society For Ethnomusicology David Seubert Jonathan Kertzer Alternate: Bill Klinger Alternate: Alan Burdette Audio Engineering Society Songwriters Hall of Fame George Massenburg Linda Moran Alternate: Elizabeth Cohen Alternate: Robbin Ahrold Broadcast Music, Incorporated At-Large Michael O'Neill Michael Feinstein Alternate: Michael Collins At-Large Country Music Foundation Brenda Nelson-Strauss Kyle Young Alternate: Eileen Hayes Alternate: Alan Stoker At-Large Digital Media Association Mickey Hart Garrett Levin Alternate: ChristoPher H. Sterling Alternate: Sally Rose Larson At-Large Music Business Association Bob Santelli Portia Sabin Alternate: Al Pryor Alternate: Paul JessoP At-Large Music Library Association Eric Schwartz James Farrington Alternate: John Simson Alternate: Maristella Feustle Abstract: The Music Modernization Act is reviewed in detail, with a Particular eye toward the implications for members of the community suPPorted by the National Recording Preservation Board, including librarians, archivists, and Private collectors. The guide attemPts an exhaustive treatment using Plain but legally precise language. -

ELDRED V. ASHCROFT: the CONSTITUTIONALITY of the COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION ACT by Michaeljones

COPYRIGHT ELDRED V. ASHCROFT: THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION ACT By MichaelJones On January 15, 2003, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Copyright Term Extension Act ("CTEA"), which extended the term of copyright protection by twenty years.2 The decision has been ap- plauded by copyright protectionists who regard the extension as an effec- tive incentive to creators. In their view, it is a perfectly rational piece of legislation that reflects Congress's judgment as to the proper copyright term, balances the interests of copyright holders and users, and brings the3 United States into line with the European Union's copyright regime. However, the CTEA has been deplored by champions of a robust public domain, who see the extension as a giveaway to powerful conglomerates, which runs contrary to the public interest.4 Such activists see the CTEA as, in the words of Justice Stevens, a "gratuitous transfer of wealth" that will impoverish the public domain. 5 Consequently, Eldred, for those in agree- ment with Justice Stevens, is nothing less than the "Dred Scott case for 6 culture." The Court in Eldred rejected the petitioners' claims that (1) the CTEA did not pass constitutional muster under the Copyright Clause's "limited © 2004 Berkeley Technology Law Journal & Berkeley Center for Law and Technology. 1. Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, 17 U.S.C. §§ 108, 203, 301-304 (2002). The Act's four provisions consider term extensions, transfer rights, a new in- fringement exception, and the division of fees, respectively; this Note deals only with the first provision, that of term extensions. -

The Exhaustion Doctrine in the United States

IP Exhaustion around the World: Differing Approaches and Consequences to the Reach of IP Protection beyond the First Sale The Exhaustion Doctrine in the United States NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONAL LAW AND PRACTICE SECTION FALL MEETING—2013 HANOI, VIETNAM L. Donald Prutzman Tannenbaum Helpern Syracuse & Hirschtritt LLP 900 Third Avenue New York, New York 10022 (212) 508-6739 -and- Eric Stenshoel Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle, LLP 101 Park Avenue New York, NY 10178-0061 (212) 696-8878 The Exhaustion Doctrine in the United States L. Donald Prutzman and Eric Stenshoel I. Overview Intellectual property rights are limited monopolies a government grants for the use or distribution of products that embody or use the intellectual property, whether a patented invention, a copyrighted work, or a brand name protected by a trademark. The value of the intellectual property right depends upon both the underlying demand for the products subject to the patent, copyright or trademark, and the ability of the rights holder to exploit the monopoly position. One traditional means of maximizing returns on a monopoly position is to divide markets among different licensees by putting various restrictions on their use of the licensed intellectual property. These restrictions can be, for example, limited geographic territories, or limitations on the field of use or market segment. Patentees can use field of use restrictions in the biopharma industry, for example, to distinguish uses of an invention in the diagnostic, therapeutic and research markets, or in human and animal applications. Copyright owners may grant separate licenses for hard cover and soft cover books, for manufacture and sale in different countries or for different language editions. -

Guarding Against Abuse: the Costs of Excessively Long Copyright Terms

GUARDING AGAINST ABUSE: THE COSTS OF EXCESSIVELY LONG COPYRIGHT TERMS By Derek Khanna* I. INTRODUCTION Copyrights are intended to encourage creative works through the mechanism of a statutorily created1 limited property right, which some prominent think tanks and congressional organizations have referred to as a form of govern- ment regulation.2 Under both economic3 and legal analysis,4 they are recog- * Derek Khanna is a fellow with X-Lab and a technology policy consultant. As a policy consultant he has never worked for any organizations that lobby or with personal stakes in copyright terms, and neither has Derek ever lobbied Congress. He was previously a Yale Law School Information Society Project Fellow. He was featured in Forbes’ 2014 list of top 30 under 30 for law in policy and selected as a top 200 global leader of tomorrow for spear- heading the successful national campaign on cell phone unlocking which led to the enact- ment of copyright reform legislation to legalize phone unlocking. He has spoken at the Con- servative Political Action Conference, South by Southwest, the International Consumer Electronics Show and at several colleges across the country as a paid speaker with the Fed- eralist Society. He also serves as a columnist or contributor to National Review, The Atlan- tic and Forbes. He was previously a professional staff member for the House Republican Study Committee, where he authored the widely read House Republican Study Committee report “Three Myths about Copyright Law.” 1 See Edward C. Walterscheld, Defining the Patent and Copyright Term: Term Limits and the Intellectual Property Clause, 7 J. -

1 Golan V. Holder

Golan v. Holder: A Farewell to Constitutional Challenges to Copyright Laws Jonathan Band [email protected] On January 13, 2012, the Supreme Court by a 6-2 vote affirmed the Tenth Circuit decision in Golan v. Holder. (Justice Kagan recused herself, presumably because of her involvement in the case while she was Solicitor General.) The case concerned the constitutionality of the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA), which restored copyright in foreign works that had entered into the public domain because the copyright owners had failed to comply with formalities such as notice; or because the U.S. did not have copyright treaties in place with the country at the time the work was created (e.g., the Soviet Union). The petitioners were orchestra conductors, musicians, and publishers who enjoyed free access to works removed by URAA from the public domain. The Court in its decision made clear that constitutional challenges to a copyright statute would not succeed so long as the provision does not have an unlimited term, and does not tread on the idea/expression dichotomy or the fair use doctrine. Justice Breyer wrote a strong dissent that contains many interesting observations concerning the economic theory of copyright; how the URAA reflects a European rather than American approach to copyright; orphan works; and the causes of infringement. The American Library Association (ALA), the Association of Research Libraries (ARL), and the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) joined an amicus brief written by Electronic Frontier Foundation in support of reversal. This brief, referred to as the ALA brief, received significant attention in both the majority and dissenting opinions. -

What Does the WTO Analysis of 17 USC ß 110(5) Mean

Sarah E. Henry The First International Challenge to U.S. Copyright Law: What Does the WTO Analysis of 17 U.S.C. ß 110(5) Mean to the Future of International Harmonization of Copyright Laws Under the TRIPS Agreement? 20 Penn State International Law Review 301 (2001) I. Introduction June 15, 2000 was a landmark date in the development of international copyright law. A World Trade Organization ("WTO") dispute settlement body ("Panel") published a panel report, which 2 found that Section 110(5) of the United States Copyright Act of 19761 as amended in 1998, was incompatible with US obligations under the Uruguay Round Multilateral Agreement on Trade- Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights ("TRIPS Agreement")3. 4 The Panel has recom- mended that the US amend 110(5) in order to conform with the TRIPS Agreement. 5 At issue was the Fairness in Music Licensing Act ("FMLA"), an amendment to Section 110(5) enacted by Congress in October, 1998.6 The same day FMLA became law on January 26, 1999, the European Community ("EC"), comprised of fifteen-member nations,7 brought a challenge under the World Trade Organization's dispute settlement procedures.8 The EC complaint, fueled initially by complaints from performers' rights organizations,9 concluded that the practical effect of the FMLA resulted in royalty losses totaling approximately Euro 28 million per annum.10 Thereafter, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, and Switzerland joined in the EC complaint, participating in formal discus- 1 United States Copyright Act of 1976, Act of Oct. 19, 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-553, 90 Stat.