Comprehensive NATO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

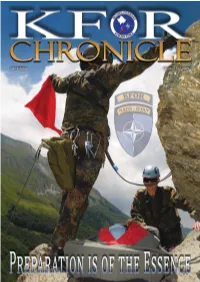

2009-10 KFOR Chronicle:Layout 1.Qxd

10 years ago, I was tasked to train and prepare the first Austrian contingent for KFOR. Although this is my first tour in Kosovo, I was quite impressed with the development of the mission and the country during the past 10 years. The development was successful because a large number of soldiers served in a very professional way to include the numerous organizations working in KOSOVO and the people living here. “We are truly “MOVING FORWARD”. Nevertheless, most of us will agree that many issues remain to be solved and more time is needed to heal the wounds of the conflict. As a professional soldier, I always look forward, and from this prospective the question arise: “Can we do our mission even with less people and means?” We will soon enter the new phase called “Deterrent Presence”. According to our success the number of forces will shrink. In this respect, I think we also have to look for new ways of seeing opportunities and not only challenges. According to the outlay of mission, the Multinational Battle Groups (MNBG) will remain self-sustaining in many ways. The logistic footprint will still be quite impressive. In the months to come we will have to prove that every soldier is mission necessary. Intelligence and logistic could be fields of extended cooperation between nations and MNBG in the future. A Joint Logistic Support Group (JLSG) will take over some of the responsibilities each nation had to sustain on their own so far. To implement this new structure in KFOR, it will not be an easy process, but the concept of JLSG will be tested in reality in theater. -

Italy's Atlanticism Between Foreign and Internal

UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 25 (January / Enero 2011) ISSN 1696-2206 ITALY’S ATLANTICISM BETWEEN FOREIGN AND INTERNAL POLITICS Massimo de Leonardis 1 Catholic University of the Sacred Heart Abstract: In spite of being a defeated country in the Second World War, Italy was a founding member of the Atlantic Alliance, because the USA highly valued her strategic importance and wished to assure her political stability. After 1955, Italy tried to advocate the Alliance’s role in the Near East and in Mediterranean Africa. The Suez crisis offered Italy the opportunity to forge closer ties with Washington at the same time appearing progressive and friendly to the Arabs in the Mediterranean, where she tried to be a protagonist vis a vis the so called neo- Atlanticism. This link with Washington was also instrumental to neutralize General De Gaulle’s ambitions of an Anglo-French-American directorate. The main issues of Italy’s Atlantic policy in the first years of “centre-left” coalitions, between 1962 and 1968, were the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Italy as a result of the Cuban missile crisis, French policy towards NATO and the EEC, Multilateral [nuclear] Force [MLF] and the revision of the Alliance’ strategy from “massive retaliation” to “flexible response”. On all these issues the Italian government was consonant with the United States. After the period of the late Sixties and Seventies when political instability, terrorism and high inflation undermined the Italian role in international relations, the decision in 1979 to accept the Euromissiles was a landmark in the history of Italian participation to NATO. -

Delpaese E Le Forze Armate

L’ITALIA 1945-1955 LA RICOSTRUZIONE DEL PAESE STATO MAGGIORE DELLA DIFESA UFFICIO STORICO E LE Commissione E LE FORZE ARMATE Italiana Storia Militare MINISTERO DELLA DIFESA CONGRESSOCONGRESSO DIDI STUDISTUDI STORICISTORICI INTERNAZIONALIINTERNAZIONALI CISM - Sapienza Università di Roma ROMA, 20-21 NOVEMBRE 2012 Centro Alti Studi per la Difesa (CASD) Palazzo Salviati ATTI DEL CONGRESSO PROPRIETÀ LETTERARIA tutti i diritti riservati: Vietata anche la riproduzione parziale senza autorizzazione © 2014 • Ministero della Difesa Ufficio Storico dello SMD Salita S. Nicola da Tolentino, 1/B - Roma [email protected] A cura di: Dott. Piero Crociani Dott.ssa Ada Fichera Dott. Paolo Formiconi Hanno contribuito alla realizzazione del Congresso di studi storici internazionali CISM Ten. Col. Cosimo SCHINAIA Capo Sezione Documentazione Storica e Coordinamento dell’Ufficio Storico dello SMD Ten. Col. Fabrizio RIZZI Capo Sezione Archivio Storico dell’Ufficio Storico dello SMD CF. Fabio SERRA Addetto alla Sezione Documentazione Storica e Coordinamento dell’Ufficio Storico dello SMD 1° Mar. Giuseppe TRINCHESE Capo Segreteria dell’Ufficio Storico dello SMD Mar. Ca. Francesco D’AURIA Addetto alla Sezione Archivio Storico dell’Ufficio Storico dello SMD Mar. Ca. Giovanni BOMBA Addetto alla Sezione Documentazione Storica e Coordinamento dell’Ufficio Storico dello SMD ISBN: 978-88-98185-09-2 3 Presentazione Col. Matteo PAESANO1 Italia 1945-1955 la ricostruzione del Paese el 1945 il Paese è un cumulo di macerie con una bassissima produzione industriale -

Strike Sorties, Including 463 Conducted by US Aircraft

The Air Force, technically in a supporting role, has been front and center. The Libya Mission By Amy McCullough, Senior Editor hen US Air Forces Af- of the continent, and the command’s to prepare for a potential contingency rica stood up in Octo- role began to change. After the leaders operation there. ber 2008, the original of Tunisia and Egypt were overthrown Planning lasted until March 17 when vision for the com- in popular revolutions, Libyan dicta- the United Nations Security Council mand centered around tor Muammar Qaddafi essentially approved a resolution authorizing the low intensity conflict scenarios, hu- declared war on his civilian population use of force to protect civilians in Wmanitarian relief missions, and training in a bid to stay in power. Officials at Libya, including a no-fly zone over and advising African partner militaries. Ramstein Air Base in Germany, where the restive North African state. The But by mid-February 2011, conflicts AFAFRICA is based, began working measure, which came five days after had erupted across much of the north closely with US and coalition countries the Arab League called on the Security 28 AIR FORCE Magazine / August 2011 Council to establish a no-fly zone, called for an “immediate cease-fire and a complete end to violence and all attacks against, and abuses of, civil- ians” targeted by Qaddafi and forces loyal to him. USAF photo by SSgt. Marc LaneI. Opening Days Two days later, US and British warships based in the Mediterranean launched more than 100 long-range Tomahawk cruise missiles against Libyan air defenses—kick-starting Operation Odyssey Dawn. -

AGENDA 32Nd Intl Wkshp Paris Nov 2015

#32iws Revised 4 November 2015 Workshop Agenda Patron Mr. Jean-Yves Le Drian Minister of Defense of France Patron of the 30th, 31st and 32nd International Workshops on Global Security Theme Facing the Emerging Security Challenges: From Crimea to Cyber Security Workshop Chairman & Founder Dr. Roger Weissinger-Baylon Co-Director, Center for Strategic Decision Research Presented by Center for Strategic Decision Research (CSDR) Institut des hautes études de défense nationale (IHEDN), and within the French Prime Minister’s organization · Including the Castex Chair of Cyber Strategy Principal Sponsors French Ministry of Defense United States Department of Defense · Office of the Director of Net Assessment North Atlantic Treaty Organization · Public Diplomacy Major Sponsors Lockheed Martin · McAfee, Intel Security · MITRE Tiversa · Area SpA · FireEye Associate Sponsors Kaspersky Lab · AECOM Quantum Research International Acknowledgements to Past Patrons, Honorary General Chairmen, Host Governments, and Keynote Speakers Patrons His Excellency Jean-Yves Le Drian, Minister of Defense of France (2013, 2014, 2015) His Excellency Giorgio Napolitano, President of the Italian Republic (2012) His Excellency Gérard Longuet, Minister of Defense of France (2011) State Secretary Rüdiger Wolf, Ministry of Defense of Germany (2010) His Excellency Vecdi Gönül, Minister of Defense of Turkey (2009) His Excellency Ignazio La Russa, Minister of Defense of Italy (2008) His Excellency Hervé Morin, Minister of Defense of France (2007) His Excellency Franz Josef Jung, MdB, Minister of Defense of Germany (2006) Her Excellency Michèle Alliot-Marie, Minister of Defense of France (2005, 2007) His Excellency Aleksander Kwasniewski, President of Poland (1996–98, 2000, 2002) His Excellency Václav Havel, President of the Czech Republic (1996, 1997) His Excellency Peter Struck, MdB, Minister of Defense of Germany (2004) His Excellency Rudolf Scharping, Minister of Defense of Germany (2000, 2002) His Excellency Dr. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

NATO – Wikipedia Seite 1 von 24 NATO Koordinaten: 50° 52′ 34″ N, 4° 25′ 19″ O aus Wikipedia, der freien Enzyklopädie Die NATO (englisch North Atlantic Treaty Organization North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) „Organisation des Nordatlantikvertrags“ bzw. Organisation du traité de l’Atlantique Nord (OTAN) Nordatlantikpakt-Organisation; im Deutschen häufig als Atlantisches Bündnis bezeichnet) oder OTAN (französisch Organisation du Traité de l’Atlantique Nord) ist eine Internationale Organisation, die den Nordatlantikvertrag, ein militärisches Bündnis von 28 europäischen und nordamerikanischen Staaten, umsetzt.[4] Das NATO- Hauptquartier beherbergt mit dem Nordatlantikrat das Hauptorgan der NATO; diese Institution hat seit 1967 ihren Sitz in Brüssel. Nach der Unterzeichnung des Nordatlantikpakts am 4. April 1949 – zunächst auf 20 Jahre Flagge der NATO – war das Hauptquartier zunächst von 1949 bis April 1952 in Washington, D.C., anschließend war der Sitz vom 16. April 1952 bis 1967 in Paris eingerichtet worden.[5] Inhaltsverzeichnis ◾ 1 Geschichte und Entwicklung ◾ 1.1 Vorgeschichte ◾ 1.2 Entwicklung von 1949 bis 1984 ◾ 1.2.1 Zwei-Pfeiler-Doktrin ◾ 1.3 Entwicklung von 1985 bis 1990 ◾ 1.4 Entwicklung von 1991 bis 1999 ◾ 1.5 Entwicklung seit 2000 ◾ 1.5.1 Terroranschläge in den USA am 11. September 2001 ◾ 1.5.2 ISAF-Einsatz in Afghanistan ◾ 1.5.3 Irak-Krise Generalsekretär Jens Stoltenberg [1][2] ◾ 1.5.4 Libyen (seit 2014) ◾ 1.5.5 Türkei SACEUR (Supreme US-General Philip M. ◾ 1.6 Krisen-Reaktionstruppe der NATO Allied Commander Breedlove (seit 13. Mai 2013) Europe) ◾ 1.7 NATO-Raketenabwehrprogramm SACT (Supreme Allied General (FRA) Jean-Paul ◾ 2 Auftrag Commander Paloméros (seit September ◾ 2.1 Rechtsgrundlage Transformation) 2012) ◾ 2.2 Aufgaben und Ziele Gründung 4. -

NATO's Strategic Concept

Istituto Affari Internazionali DOCUMENTI IAI 10 | 23 – November 2010 NATO’s Strategic Concept: Back to the Future Interview with Giampaolo Di Paola by Alessandro Marrone Abstract The NATO reflection on the new Strategic Concept is moving to its conclusion, and there are some steps forward about important issues such as missile defence and cyber security. The NATO Military Committee Chairman, Admiral Giampaolo Di Paola, comments on that in this interview focused on the upcoming Lisbon Summit where the new Strategic Concept will be approved. Keywords : NATO’s military doctrine / Missile defence / Cyber-security / Energy supply security / Afghanistan / US foreign policy / Russia / Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) / European Union / NATO-EU cooperation © 2010 IAI Documenti IAI 1023 NATO’s Strategic Concept: Back to the Future NATO’s Strategic Concept: Back to the Future Interview with Giampaolo Di Paola by Alessandro Marrone ∗ The NATO reflection on the new Strategic Concept is moving to its conclusion, and there are some steps forward about important issues such as missile defence and cyber security. The NATO Military Committee Chairman, Admiral Giampaolo Di Paola, comments on that in this interview focused on the upcoming Lisbon Summit where the new Strategic Concept will be approved. NATO’s Defence and Foreign Affairs Ministers in their meeting last October discussed, among other things, the draft of the new Strategic Concept. What was said about it? During the Ministerial meeting Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen presented his draft of the Strategic Concept, in order to have a validation by the Ministers that his work is going in the right direction. -

Biographies of the Speakers.Pdf

Biographies of the speakers 1. Elana Wilson Rowe Elana Wilson Rowe holds a PhD (2006) in Geography from the University of Cambridge. She is a research professor at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and an adjunct professor in energy politics at the High North Centre for Business and Governance at Nord University (Bodø, Norway). Wilson Rowe’s research areas include Arctic governance, Russia’s Arctic and foreign policymaking, and ocean governance. She is the author of Russian Climate Politics: When Science Meets Policy (Palgrave, 2013) and Arctic Governance: Power in cross-border relations (University of Manchester, 2018). She was a member of Norway’s committee establishing research priorities for the UN Ocean Decade and is currently leading a five-year research project funded by the European Research Council comparing the politics of the Arctic, Amazon Basin and the Caspian Sea (‘The Lorax Project’, #loraxprojectERC). 2. Nils Wang Rear Admiral Nils Wang is one of Denmark’s leading analysts on issues related to geo-politics, Arctic security and the relationship between Denmark and Greenland. Before he became Director of Naval Team Denmark he was Commandant of the Danish Defence College and he was Head of the Royal Danish Navy from 2005 to 2010. Rear Admiral Nils Wang´s more than ten years of active sea duty in the Danish Navy includes 5 years in Arctic Waters around Greenland. In 2015 Rear Admiral Nils Wang was appointed to be part of the Taksøe-Jensen Advisory Group, assisting the development of a new set of priorities for Denmark´s future foreign and defence policies and he is presently part of an Government Expert Panel attached to a Defence related National Security Analysis. -

Summer 2018 Full Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 71 Article 1 Number 3 Summer 2018 2018 Summer 2018 Full Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2018) "Summer 2018 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 71 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol71/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Summer 2018 Full Issue Summer 2018 Volume 71, Number 3 Summer 2018 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2018 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 71 [2018], No. 3, Art. 1 Cover The Navy’s unmanned X-47B flies near the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roo- sevelt (CVN 71) in the Atlantic Ocean in August 2014. The aircraft completed a series of tests demonstrating its ability to operate safely and seamlessly with manned aircraft. In “Lifting the Fog of Targeting: ‘Autonomous Weapons’ and Human Control through the Lens of Military Targeting,” Merel A. C. Ekelhof addresses the current context of increas- ingly autonomous weapons, making the case that military targeting practices should be the core of any analysis that seeks a better understanding of the concept of meaningful human control. -

Globsec Nato Adaptation Initiative

GLOBSEC NATO ADAPTATION INITIATIVE ONE ALLIANCE The Future Tasks of the Adapted Alliance www.globsec.org 2 GLOBSEC NATO ADAPTATION INITIATIVE GLOBSEC NATO ADAPTATION INITIATIVE ONE ALLIANCE The Future Tasks of the Adapted Alliance PRESENTATION FOLDER: COLLECTION OF PAPERS ONE ALLIANCE THE FUTURE TASKS OF THE ADAPTED ALLIANCE The GLOBSEC NATO Adaptation Initiative, led by General (Retd.) John R. Allen, is GLOBSEC’s foremost contribution to debates about the future of the Alliance. Given the substantial changes within the global security environment, GLOBSEC has undertaken a year-long project, following its annual Spring conference and the July NATO Summit in Warsaw, to explore challenges faced by the Alliance in adapting to a very different strategic environment than that of any time since the end of the Cold War. The Initiative integrates policy expertise, institutional knowledge, intellectual rigour and industrial perspectives. It ultimately seeks to provide innovative and thoughtful solutions for the leaders of the Alliance to make NATO more a resilient, responsive and efficient anchor of transatlantic stability. The policy papers published within the GLOBSEC NATO Adaptation Initiative are authored by the Initiative’s Steering Committee members: General (Retd.) John R. Allen, Admiral (Retd.) Giampaolo di Paola, General (Retd.) Wolf Langheld, Professor Julian Lindley-French, Ambassador (Retd.) Tomáš Valášek, Ambassador (Retd.) Alexander Vershbow and other acclaimed authorities from the field of global security and strategy. 4 GLOBSEC NATO ADAPTATION INITIATIVE CREDITS CREDITS GLOBSEC NATO Adaptation Initiative Steering Committee General (Retd.) John R. Allen1, Professor Dr Julian Lindley-French, Admiral (Retd.) Giampaolo Di Paola, General (Retd.) Wolf Langheld, Ambassador (Retd.) Tomáš Valášek, Ambassador (Retd.) Alexander Vershbow Observers and Advisors General (Retd.) Knud Bartels, James Townsend, Dr Michael E. -

After Chicago: Re-Evaluating NATO's Priorities

After Chicago: Re-evaluating NATO’s priorities Report International conference Friday 25 May 2012 Palais d’Egmont, Brussels With the support of The views expressed in this report are personal opinions of the speakers and not necessarily those of the organisations they represent, nor of the Security & Defence Agenda, its members or partners. Reproduction in whole or in part is permitted, providing that full attribution is made to the Security & Defence Agenda and to the source(s) in question, and provided that any such reproduction, whether in full or in part, is not sold unless incorporated in other works. A Security & Defence Agenda Report Rapporteur: Jonathan Dowdall Photos: Philippe Molitor Publisher: Geert Cami Table of contents Foreword 2 Programme and speakers 4 Report 9 2012 Security Jam 18 10th Anniversary Presidents’ Dinner 28 List of participants 30 After Chicago: Re-evaluating NATO’s priorities 1 Foreword The SDA’s annual NATO conference once again gave us an opportunity to gather stakeholders from the defence and security sectors for an open and valuable discussion. This SDA conference followed hard on the heels of NATO’s Chicago summit, which made it plain that the challenges facing the Alliance remain numerous and complex, with the question marks over NATO’s post-Cold War raison d’être yet to be satisfactorily answered. Profound shifts in the geopolitical balance, in particular the economic and military rise of Asian powers is being paralleled by global financial turmoil. This report aims to provide food for thought for NATO and national leaders, for it still remains to be seen whether the alliance’s political leaders will find the courage needed to resolve the security and defence issues that confront us all. -

NATO's Military Committee

The International Military Staff (IMS) Six functional areas The IMS supports the Military Committee, with about The Military Committee oversees of the IMS 400 dedicated military and civilian personnel working several operations and missions in an international capacity for the common interest including the: Plans and Policy of the Alliance, rather than on behalf of their country Responsible for strategic level plans of origin. Under the direction of the Director, Dutch ➤ International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan and policies, and defence/force Lt.-Gen. Jo Godderij, the staff prepare assessments, (ISAF). NATO now is operating throughout Afghanistan with about 43,000 military personnel there under planning, including working with evaluations and reports on all issues that form the nations to determine national military its command. ISAF has responsibility for, among basis of discussion and decisions in the MC. NATO’s Military levels of ambition regarding force other things, the provision of security, Provincial goals and contributions to NATO. Reconstruction Teams, and training the Afghan National The IMS is also responsible for planning, assessing Army. Operations and recommending policy on military matters Committee Closely tracks current operations, for consideration by the Military Committee, ➤ Kosovo Force (KFOR). Since June 1999 NATO has led Operation Active Endeavour is NATO’s maritime a peacekeeping operation in Kosovo. Initially composed surveillance and escort operation in the fight against staffs operational planning, follows and for ensuring their policies and decisions are terrorism. Based in the Mediterranean Sea, the force, of 50,000 following the March 1999 air campaign, the NATO exercises and training, and implemented as directed.