Converted by Filemerlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three Minor Revisions

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2001 The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions John Donald Hosler Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Hosler, John Donald, "The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions" (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 21277. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/21277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions by John Donald Hosler A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Major Professor: Kenneth G. Madison Iowa State University Ames~Iowa 2001 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of John Donald Hosler has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 The liberal arts had not disappeared, but the honours which ought to attend them were withheld Gerald ofWales, Topograhpia Cambria! (c.1187) IV TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION 1 Overview: the Reign of Henry II of England 1 Henry's Conflict with Thomas Becket CHAPTER TWO. -

Anglo-Norman Views on Frederick Barbarossa and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa Citation for published version: Raccagni, G 2014, 'English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa' Quaderni Storici, vol. 145, pp. 183-218. DOI: 10.1408/76676 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1408/76676 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaderni Storici Publisher Rights Statement: © Raccagni, G. (2014). English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. Quaderni Storici, 145, 183-218. 10.1408/76676 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick Barbarossa* [A head]Introduction In the preface to his edition of the chronicle of Roger of Howden, William Stubbs briefly noted how well English chronicles covered the conflicts between Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and the Lombard cities.1 Unfortunately, neither Stubbs nor his * I wish to thank Bill Aird, Anne Duggan, Judith Green, Elisabeth Van Houts and the referees of Quaderni Storici for their suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this work. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Heineman Royal Ancestors Medieval Europe

HERALDRYand BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE HERALDRY and BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE INTRODUCTION After producing numerous editions and revisions of the Another way in which the royal house of a given country familiy genealogy report and subsequent support may change is when a foreign prince is invited to fill a documents the lineage to numerous royal ancestors of vacant throne or a next-of-kin from a foreign house Europe although evident to me as the author was not clear succeeds. This occurred with the death of childless Queen to the readers. The family journal format used in the Anne of the House of Stuart: she was succeeded by a reports, while comprehensive and the most popular form prince of the House of Hanover who was her nearest for publishing genealogy can be confusing to individuals Protestant relative. wishing to trace a direct ancestral line of descent. Not everyone wants a report encumbered with the names of Unlike all Europeans, most of the world's Royal Families every child born to the most distant of family lines. do not really have family names and those that have adopted them rarely use them. They are referred to A Royal House or Dynasty is a sort of family name used instead by their titles, often related to an area ruled or by royalty. It generally represents the members of a family once ruled by that family. The name of a Royal House is in various senior and junior or cadet branches, who are not a surname; it just a convenient way of dynastic loosely related but not necessarily of the same immediate identification of individuals. -

Notes and Documents

286 SOGEB OF WENDOVEB April Notes and Documents. Roger of Wendover and the Coggeshall Chronicle. Downloaded from KALFH, abbot of Coggeshall from 1207 until his resignation in* 1218, is said' to have begun his share of the monastic chronicle •with the account of the capture of the Holy Cross (1187). He took a special interest in the stories which came from the Holy Land, and his narrative is very valuable. It tells us what http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ Englishmen at home knew of the third crusade. The captivity of Eichard gave Ralph a fresh opportunity, for Anselm, the royal chaplain, brought the report of an eye-witness, which was inserted in the new chronicle. The personal history of the king is the central theme during these years. A period which finds a unity and completeness outside England, in which other English and even European events are of secondary importance, closes with by guest on August 11, 2015 Richard's return from captivity and Count John's submission in 1194. Now it is significant that just here, after a supplementary account of the Saracens in Spain, the ink and style of writing change in the original manuscript. Down to this point, with the exception of a few corrections and additions the manuscript and all its various alterations are the work of the same scribe. The entries under the year 1195 are in another hand.1 It would be quite in accord with monastic usage if copies of this earlier portion were sent elsewhere. Such was the case, for example, with Robert of Torigny's chronicle. -

Crusades, Martyrdoms, and the Jews of Norman England, 1096-1190

Crusades, Martyrdoms, and the Jews of Norman England, 1096-1190 BY ROBERT C. STACEY A connection between crusading and anti-Jewish violence was forged in 1096, first in northern France, and then, most memorably, in the cataclysmic events of the Rhineland. Thereafter, attacks on Jews and Jewish communities became a regulär feature of the cru sading movement, despite the efforts of ecclesiastical and secular authorities to prevent them. The Second Crusade saw renewed assaults in the Rhineland and northern France. In the Third Crusade, assaults in the Rhineland recurred, but the worst violence this time oc curred in England, where something on the order of 10% of the entire Jewish Community in England perished in the massacres of 11891190. After the 1190s, however, direct mob violence by crusaders against Jews lessened. Although Crusades would continue to pro voke antiJewish hostility, no further armed assaults on Jewish communities, on the scale of those that took place between 1096 and 1190, would accompany the thirteenth Century 1 Crusades ^. The connection we are attempting to explain, between crusading and armed at tacks on Jewish communities, is thus distinctly a phenomenon of the twelfth Century provided, of course, that we may begin our twelfth Century in 1096. Attempts to analyze this connection between crusading and antiJewish assaults have generally focused on the First Crusade. This is understandable, and by no means misguid ed. Thanks to the work of Jonathan RileySmith, Robert Chazan, Jeremy Cohen, Yisrael Yuval, Ivan Marcus, Kenneth Stow and others, we now understand far more about the background, nature, and causes of the events of 1096 than we did a generation ago. -

Women in the Royal Succession of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291)*

Women in the Royal Succession of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291)* Alan V. Murray (Leeds UK) »During this time Baldwin, king of Jerusalem, died, leaving adaughter of marriageable age (for he lacked ason) as heir to the kingdom, which wasdeservedly divided against it- self, forsaken on account of itssins, and despised by the pagans, since it had passed into the hands of agirl, in what wasnogoodomen for government. For each of the foremost men of the kingdom desired to becomeruler and wanted to secure the girl and the royal inheritance by marriage –tohimself, if he lacked awife,tohis son, if he wasmarried, or to akinsman,ifhehad no son of his own;this caused the greatestill-will among them, which led to the destruction of the kingdom. Yet she, spurning the natives of the realm, took up with Guy, countofAscalon, anew arrival of elegantappearance and proven courage, and, with the approval of both the patriarch and the knights of the Temple, took him as her husband and conferred the kingdom on him«1). *) Dates given in parentheses in this essay relate to the reigns of the individualsaskings or queens of Je- rusalem.For ease of reference, royal documents issued in the kingdom of Jerusalem will be given accord- ing to their number in: Die Urkunden der lateinischen Könige vonJerusalem, ed. Hans EberhardMayer, 4vols. (MGH Diplomata Regum LatinorumHierosolymitanorum), Hanover 2010 (cited henceforth as D/DDJerus.), as well as those in the calendared forms given in: Regesta Regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII–MCCXCI), ed. Reinhold Rçhricht, 2vols.,Innsbruck 1893–1904 (cited henceforth as RRH), which has been widely used in earlier scholarship. -

Commemoration of the Eighth Centenary of the Birth of James I

CATALAN HISTORICAL REVIEW, 1: 149-155 (2008) Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona DOI: 10.2436/20.1000.01.10 · ISSN: 2013-407X http://revistes.iec.cat/chr/ Commemoration of the Eighth Centenary of the Birth of James I: Conference Organized by the History and Archeology Section of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans in Barcelona Maria Teresa Ferrer* Institut d’Estudis Catalans We are commemorating this year, 2008, the eighth cente- ternational Relations). A total of two lectures and twen- nary of the birth of James I ‘the Conqueror’, the son of King ty-four papers were given. Peter I ‘the Catholic’ and Mary of Montpellier, who was At the opening session the President of the Institut born in Montpellier during the night of 1-2 February 1208. d’Estudis Catalans, Salvador Giner, and the Director of He was unquestionably the most important of our the Institut Europeu de la Mediterrània, Senén Florensa, kings, both on account of his conquests and because of both spoke about the eighth centenary celebrations and the governmental action he carried out during his long, two lectures were given. In the first of these Maria Teresa sixty-three-year reign. Ferrer of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans offered a outline To the states he inherited − Aragon, Catalonia and the biography of King James I and an assessment of his reign. seigneury of Montpellier − he added two more − Majorca She referred to the aspects of his rule that were to be stud- and the Valencian Country − which were captured from ied in each of the conferences and recalled the historian the Moors, resettled, and organized as kingdoms in their Robert I. -

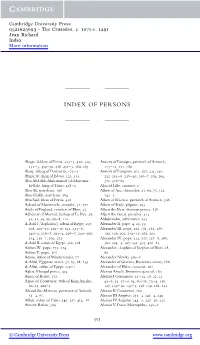

Index of Persons

Cambridge University Press 0521623693 - The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291 Jean Richard Index More information ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ INDEX OF PERSONS ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ Abaga, il-khan of Persia, 423±4, 426, 429, Aimery of Limoges, patriarch of Antioch, 432±3, 439±40, 446, 452±3, 460, 463 113±14, 171, 180 Abaq, atabeg of Damascus, 173±4 Aimery of Lusignan, 201, 207, 225, 230, Abgar, St, king of Edessa, 122, 155 232, 235±6, 238±40, 256±7, 264, 294, Abu Abdallah Muhammad (al-Mustansir 371, 376±80 bi-llah), king of Tunis, 428±9 Alan of Lille, canonist, 2 Abu Ali, merchant, 106 Albert of Aix, chronicler, 21, 69, 75, 123, Abu Ghalib, merchant, 384 142±3 Abu Said, khan of Persia, 456 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Antioch, 396 Achard of Montmerle, crusader, 31, 271 Albert of Stade, pilgrim, 293 Adela of England, countess of Blois, 35 Albert the Bear, German prince, 158 AdheÂmar of Monteil, bishop of Le Puy, 28, Albert the Great, preacher, 413 32, 42, 49, 60, 66±8, 112 Aldobrandin, adventurer, 254 al-Adil I (`Saphadin'), sultan of Egypt, 197, Alexander II, pope, 4, 23, 39 208, 209±10, 229±30, 232, 235±6, Alexander III, pope, 122, 181, 185, 188, 240±2, 256±7, 293±4, 296±7, 299±300, 190, 199, 202, 214±15, 260, 292 314, 350±1, 362, 375 Alexander IV, pope, 335, 337, 357±8, 360, al-Adil II, sultan of Egypt, 322, 328 362, 364±5, 367, 391, 397, 410±13 Adrian IV, pope, 175, 214 Alexander, chaplain of Stephen of Blois, 28, Adrian V, pope, 385 60 Adson, abbot of MontieÂrender, 17 Alexander Nevski, 360±1 al-Afdal, Egyptian vizier, 57, 65, 68, 139 Alexander of Gravina, -

Charlemagne Descent

Selected descendants of Charlemagne to the early 16th century (1 of 315) Charlemagne King of the Franks Hildegard of Vinzgau b: 742 d: 28 January 813/14 Irmengard of Hesbain Louis I "The Pious" Emperor of the West Judith of Bavaria Pepin of Italy b: 778 in Casseneuil, France d: 810 d: 20 June 840 Lothair I Holy Roman Emperor Irmengard Comtesse de Tours Louis II "The German" King of the East Emma von Bayern Gisela Eberhard Duke of Fruili Cont. p. 2 Cont. p. 3 d: 29 September 855 in Pruem, Franks b: 821 b: Abt. 815 Rheinland, Germany d: 28 August 876 d: 16 December 866 Ermengarde Princesse des Francs Giselbert II Graf von Maasgau Carloman König von Bayern Cont. p. 4 Anscar I Duke of Ivrea b: 825 b: 829 d: March 901/02 d: 14 June 877 d: 880 Reginar I Comte de Hainaut Herzog von Alberade von Kleve Adalbert I Duke of Ivrea Gisela of Fruili Lothringen d: Aft. 28 February 928/29 b: 850 d: 915 in Meerssen, The Netherlands Cont. p. 5 Cont. p. 6 Selected descendants of Charlemagne to the early 16th century (2 of 315) Louis I "The Pious" Emperor of the West b: 778 in Casseneuil, France Judith of Bavaria d: 20 June 840 Cont. p. 1 Charles II King of the West Franks Ermentrude of Orléans b: 13 June 823 b: 27 September 823 d: 6 October 877 d: 6 October 869 Judith (Princess) Baldwin I Count of Flanders Louis II King of the West Franks Adelaide de Paris b: 844 d: 858 b: 1 November 846 d: 870 d: 10 April 879 Baldwin II Count of Flanders Æfthryth Ermentrude of France Cont. -

Yüksek Lisans, Tez Dosyası

T.C. YILDIRIM BEYAZIT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ NECMETTİN AYAN TEMMUZ-2014 HAÇLI SEFERLERİ’NDE KIBRIS’IN ROLÜ (1191-1310) NECMETTİN AYAN TARAFINDAN YILDIRIM BEYAZIT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜNE SUNULAN TEZ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSAN TEZİ TEMMUZ 2014 ii Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Onayı _____________________ Prof. Dr. Erdal Tanas KARAGÖL Enstitü Müdürü Bu tezin Yüksek Lisans derecesi için gereken tüm şartları sağladığını tasdik ederim. _____________________ Prof. Dr. H. Mustafa ERAVCI Anabilim Dalı Başkanı Okuduğumuz ve savunmasını dinlediğimiz bu tezin bir Yüksek Lisans derecesi için gereken tüm kapsam ve kalite şartlarını sağladığını beyan ederim. _____________________ Doç. Dr. Fatih ERKOÇOĞLU Danışman Jüri Üyeleri: Bu tez içerisindeki bütün bilgilerin akademik kurallar ve etik davranış çerçevesinde elde edilerek sunulduğunu beyan ederim. Ayrıca bu kurallar ve davranışların gerektirdiği gibi bu çalışmada orijinal olan her tür kaynak ve sonuçlara tam olarak atıf ve referans yaptığımı da beyan ederim; aksi takdirde tüm yasal sorumluluğu kabul ediyorum. Adı Soyadı: Necmettin AYAN İmza : 4 ÖZET HAÇLI SEFERLERİ’NDE KIBRIS’IN ROLÜ (1191-1310) AYAN, Necmettin Yüksek Lisans, Tarih Bölümü Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. Fatih ERKOÇOĞLU 2014 Kıbrıs, Doğu Akdeniz’deki jeopolitik ve stratejik konumu nedeniyle ilkçağlardan beri birçok mücadeleye sahne olmuştur. Doğu Akdeniz ve Anadolu topraklarını kontrol eden güçler adanın sahip olduğu öneme binaen Kıbrıs’a sık sık saldırı düzenlemişlerdir. 1095 yılında Clermont’ta toplanan konsil sonucunda başlayan Haçlı Seferleri, Ortaçağ’ın en önemli olaylarından bir tanesidir. Yapılan seferler sadece batı tarihini değil, Doğu Akdeniz coğrafyasının tarihini de etkilemiştir. Kudüs'ün 1187 yılında Selahaddin tarafından fethedilmesinden sonra geri alınabilmesi için Kutsal Topraklara Almanya, Fransa ve İngiltere Kralları tarafından yeni bir sefer hazırlanmıştı. -

The Case of the Catalan Nation a Historical Summary

THE CASE OF THE CATALAN NATION A HISTORICAL SUMMARY THE MANAGEMENT OF THE NATION Catalonia is one of the oldest countries in Europe. It was formed during the post-Roman era, when the arrival of the Germanic people ushered in the ending of the Western-Roman Empire. The Catalan nation is composed of a mixture of Iberians, Romanized and Goths. The Visigoths installed the capital of their domains in Barcelona in 415 A.D. with an alliance with Rome that was annulled half a century later with the fall of the imperial capital (476). This strengthened the dominion covered an area of the Iberian peninsula as well as the northern part of the Pyrenees to the Septimania (Aquitaine and Narbonense), which is the Southern part of present day France. In 534 the Eastern-Roman Empire (Byzantium) incorporated the Mallorcan islands into their dominions, thereby expelling the Vandals. The subsequent invasion of Europe by the Arabs began in 711. This invasion was stopped at Poitiers, then city of the Frankish Kingdom (732), by Charles, father of Charlemagne. As of that moment the withdrawal of the Saracen Islamic invaders and the liberation of the Septimania began. Narbonne was released in 759, Girona in 785 by Charlemagne and Barcelona in 801 by Lluís, the son of Charlemagne. The Catalan counties of Pallars, Ribagorça, Urgell, Rosselló, Cerdanya, Besalú, Girona, Empúries and Barcelona were formed. The latter was to be under the main command of the Count Guifré, who died in combat against the Saracens in 897. This establish the Barcelona dynasty. The Count was a vassal to the King of the Franks.