Anglo-Norman Views on Frederick Barbarossa and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three Minor Revisions

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2001 The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions John Donald Hosler Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Hosler, John Donald, "The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions" (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 21277. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/21277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions by John Donald Hosler A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Major Professor: Kenneth G. Madison Iowa State University Ames~Iowa 2001 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of John Donald Hosler has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 The liberal arts had not disappeared, but the honours which ought to attend them were withheld Gerald ofWales, Topograhpia Cambria! (c.1187) IV TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION 1 Overview: the Reign of Henry II of England 1 Henry's Conflict with Thomas Becket CHAPTER TWO. -

Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket “Thomas a Becket” redirects here. For other uses, see Thomas a Becket (disambiguation). Thomas Becket (/ˈbɛkɪt/; also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London,[1] and later Thomas à Becket;[note 1] 21 December c. 1118 (or 1120) – 29 December 1170) was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his murder in 1170. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by both the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion. He engaged in conflict with Henry II of England over the rights and privileges of the Church and was murdered by followers of the king in Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after his death, he was Stained glass window of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral canonised by Pope Alexander III. small landowner or a petty knight.[1] Matilda was also of 1 Sources Norman ancestry,[2] and her family may have originated near Caen. Gilbert was perhaps related to Theobald of Bec, whose family also was from Thierville. Gilbert be- The main sources for the life of Becket are a number gan his life as a merchant, perhaps as a textile merchant, of biographies that were written by contemporaries. A but by the 1120s he was living in London and was a prop- few of these documents are by unknown writers, al- erty owner, living on the rental income from his prop- though traditional historiography has given them names. erties. He also served as the sheriff of the city at some The known biographers are John of Salisbury, Edward point.[1] They were buried in Old St Paul’s Cathedral. -

Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony

he collection of essays presented in “Devotional Cross-Roads: Practicing Love of God in Medieval Gaul, Jerusalem, and Saxony” investigates test case witnesses of TChristian devotion and patronage from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages, set in and between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, as well as Gaul and the regions north of the Alps. Devotional practice and love of God refer to people – mostly from the lay and religious elite –, ideas, copies of texts, images, and material objects, such as relics and reliquaries. The wide geographic borders and time span are used here to illustrate a broad picture composed around questions of worship, identity, reli- gious affiliation and gender. Among the diversity of cases, the studies presented in this volume exemplify recurring themes, which occupied the Christian believer, such as the veneration of the Cross, translation of architecture, pilgrimage and patronage, emergence of iconography and devotional patterns. These essays are representing the research results of the project “Practicing Love of God: Comparing Women’s and Men’s Practice in Medieval Saxony” guided by the art historian Galit Noga-Banai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the histori- an Hedwig Röckelein, Georg-August-University Göttingen. This project was running from 2013 to 2018 within the Niedersachsen-Israeli Program and financed by the State of Lower Saxony. Devotional Cross-Roads Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony Edited by Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover Röckelein/Noga-Banai/Pinchover Devotional Cross-Roads ISBN 978-3-86395-372-0 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover (Eds.) Devotional Cross-Roads This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

Johannes Laudage, Friedrich Barbarossa (1152–1190): Eine

Edinburgh Research Explorer Johannes Laudage, Friedrich Barbarossa (1152–1190): Eine Biografie, ed. Lars Hageneier and Matthias Schrör Citation for published version: Raccagni, G 2010, 'Johannes Laudage, Friedrich Barbarossa (1152–1190): Eine Biografie, ed. Lars Hageneier and Matthias Schrör', German Historical Institute London Bulletin, pp. 47-51. <http://www.recensio.net/rezensionen/zeitschriften/german-historical-institute-london-bulletin/vol.-xxxii- 2010/2/ReviewMonograph332756842/@@generate-pdf-recension?language=en> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: German Historical Institute London Bulletin Publisher Rights Statement: ©Raccagni, G. (2010). Johannes Laudage, Friedrich Barbarossa (1152–1190): Eine Biografie, ed. Lars Hageneier and Matthias Schrör. German Historical Institute London Bulletin, 47-51. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Citation style Raccagni, Gianluca: review of: Johannes Laudage, Friedrich Barbarossa (1152-1190). Eine Biografie, Regensburg: Pustet, 2009, in: German Historical Institute London Bulletin, Vol. XXXII (2010), 2, http://recensio.net/r/3d9667a62191ea25c4e8d73e9c2e7027 First published: German Historical Institute London Bulletin, Vol. -

![The Holy Roman Empire [1873]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7391/the-holy-roman-empire-1873-1457391.webp)

The Holy Roman Empire [1873]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Viscount James Bryce, The Holy Roman Empire [1873] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Jean Bedard Master Eckhart

Jean Bedard [email protected] Master Eckhart Translation by Richard Clark 2003 1 2 3 PREAMBLE We are in the year of grace I345, in the month of the first tulips. The sun is shining and I am preparing to leave for Bruges. I have finally decided to pull the stone from the wall of my cell, the stone which has hidden for I5 years those strange notes I compiled. I don't have the courage to reread them. I will simply add to them this short preamble and a brief conclusion, and put them back in their hiding place. Really, though, I ought to destroy them. When it was all over, and the Superior General asked me to turn in those notes he himself had ordered me to take, I did in fact hand them over, but not before I had made a copy. Just as I had predicted, the Superior General burned the pages without even so much as a glance. I don't know why I saved this copy, it's the only real disobedience I've ever been guilty of, and it is unlikely, given my age, that I will commit any others. Many times I thought of pulling out the stone, sometimes to reread my notes, sometimes to destroy them. Finally, I did neither of these two things. Today I have been assigned my final mission to Bruges, so I am leaving our monastery in Cologne for good. Not being able either to bring these parchments with me or destroy them, I will quickly add a beginning and an end, and return them to their casket of stone. -

Converted by Filemerlin

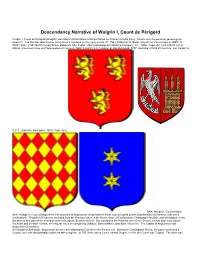

Descendancy Narrative of Wulgrin I, Count de Périgord Wulgrin I, Count de Périgord (Wulgrin I was Mayor of the Palace of King Charles Le Chauve) (André Roux: Scrolls from his personal genealogicaL research. The Number refers to the family branch numbers on his many scrolls, 87, 156.) (Roderick W. Stuart, Royalty for Commoners in ISBN: 0- 8063-1344-7 (1001 North Calvert Street, Baltimore, MD 21202, USA: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc., 1992), Page 234, Line 329-38.) (P.D. Abbott, Provinces, Pays and Seigneuries of France in ISBN: 0-9593773-0-1 (Author at 266 Myrtleford, 3737, Australia: Priries Printers Pty. Ltd, Canberra A.C.T., Australia, November, 1981), Page 329.). AKA: Wulgrin I, Count d'Agen. AKA: Wulfgrin I, Count d'Angoulême The province of Angoumois comprised the areas now occupied by the Departments of Charente, with some rectifications. Regions of Charente excluded from the Province were, in the North, those of Confolentais, Champagne Mouton, and Villelagnon; in the Southwest, that part of the arrondissement of Cognac, South of the Né. But included in the Province were Deux Sèvres, a small pays near Sauzé- Vaussais and in Haute Vienne, an irregular intrusion comprising Oradour, Saint Mathieu, and Saint Victurnien. The Capital of Angoumois was Angoulême [Charente]. At first part of Saintonge, Angoumois became an independent City late in the Roman era. During the Carolingians Period, the pays constituted a County, as it was also probably under the Mérovingiens. In 770, there was a Comte named Vulgrin; in 839, the Comte was Turpion. The latter was killed by Normans in 863. -

Notes and Documents

286 SOGEB OF WENDOVEB April Notes and Documents. Roger of Wendover and the Coggeshall Chronicle. Downloaded from KALFH, abbot of Coggeshall from 1207 until his resignation in* 1218, is said' to have begun his share of the monastic chronicle •with the account of the capture of the Holy Cross (1187). He took a special interest in the stories which came from the Holy Land, and his narrative is very valuable. It tells us what http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ Englishmen at home knew of the third crusade. The captivity of Eichard gave Ralph a fresh opportunity, for Anselm, the royal chaplain, brought the report of an eye-witness, which was inserted in the new chronicle. The personal history of the king is the central theme during these years. A period which finds a unity and completeness outside England, in which other English and even European events are of secondary importance, closes with by guest on August 11, 2015 Richard's return from captivity and Count John's submission in 1194. Now it is significant that just here, after a supplementary account of the Saracens in Spain, the ink and style of writing change in the original manuscript. Down to this point, with the exception of a few corrections and additions the manuscript and all its various alterations are the work of the same scribe. The entries under the year 1195 are in another hand.1 It would be quite in accord with monastic usage if copies of this earlier portion were sent elsewhere. Such was the case, for example, with Robert of Torigny's chronicle. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

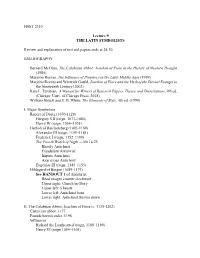

HSST 2310 Lecture 9 the LATIN SYMBOLISTS Review And

HSST 2310 Lecture 9 THE LATIN SYMBOLISTS Review and explanation of test and papers ends at 24:30 BIBLIOGRAPHY Bernard McGinn, The Calabrian Abbot: Joachim of Fiore in the History of Western Thought (1985) Marjorie Reeves, The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages (1969) Marjorie Reeves and Warwick Gould, Joachim of Fiore and the Myth of the Eternal Evangel in the Nineteenth Century (2002) Kate L. Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, 9th ed. (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2018) William Struck and E. B. White, The Elements of Style, 4th ed. (1999) I. Major Symbolists Rupert of Deutz (1070-1129) Gregory VII (reign, 1073–1085) Henry IV (reign, 1054–1105) Gerhoh of Reichersberg (1093-1169) Alexander III (reign, 1159–1181) Frederick I (reign, 1152–1190) The Fourth Watch of Night —Mt 14:25 Bloody Antichrist Fraudulent Antichrist Impure Antichrist Avaricious Antichrist Eugenius III (reign, 1145–1153) Hildegard of Bingen (1089-1179) See HANDOUT 1 of Antichrist Read images counter clockwise Upper right: Church in Glory Upper left: 5 beasts Lower left: Antichrist born Lower right: Antichrist thrown down II. The Calabrian Abbot: Joachim of Fiore (c. 1135-1202) Cistercian abbot, 1177. Founds hermit order, 1196 Influences Richard the Lionhearted (reign, 1189–1199) Henry VI (reign 1054–1105) 2 Pope Lucius III (reign, 1181–1185) Innocent III (reign, 1198–1216) Works Ten Stringed Psalter Concord of Old and New Testaments Exposition of the Apocalypse Book of Figures Influence: see Reeves in bibliography III. Joachim’s System Liber Figurarum (“Book of Figures”) See HANDOUT 2 of Liber IV. -

2019-04 Volume 2 Issue 2 the St. John

in this issue >>> Volume 2 • A possible identification of Ralph St. Issue 2 John, living in 1053. • Follow-up to an Adoption solved with Newsletter DNA. Est. 2018 • George St. John & Nancy Bryan February, March & April 2019 An Insight into the St. John Family of Highlight FOCUS ON primaryr ecords current topics >>> George St. John & Nancy Bryan Why a family newsletter Discovered Information to explain NPEs by Suzanne St. John By Suzanne St. John The descendants of George St. John and Nancy logical that the children, that appeared to have The St. Johns of Highlight, Glamorgan, Wales are Bryan have been challenging to sort out. Before been born after 1793, were both George and DNA testing came along, and before researchers Nancy’s children but exact birth dates are lost in Modern History. The individuals of this realized there were St. John and de Port-St. John unknown. family, their ancestors and descendants have been families living in America, it seemed logical to conclude that any St. Johns found in a general Berry, Thomas, William, Elizabeth, Sarah, and merged, confounded, and obliterated into non- vicinity of one another were biologically Martha do not have any descendants who have existence by well-meaning researchers, heralds, related. This was certainly true for the tested in our project. However, for Arthur, and family before us. It is our responsibility and researchers for George and Nancy. Martin and Abner we do have 7 test subjects and they don’t match their brother John’s right to honor our ancestors based on the primary What we found with DNA testing created a lot descendants. -

Pohl, B., & Allen, R. (2020). Rewriting the Gesta Normannorum Ducum At

Pohl, B. , & Allen, R. (2020). Rewriting the Gesta Normannorum ducum at Saint-Victor in the Fifteenth Century: Simon de Plumetot’s Brevis cronica compendiosa ducum Normannie. Traditio, 75, 385-435. https://doi.org/10.1017/tdo.2020.12 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1017/tdo.2020.12 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Cambridge University https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/traditio/article/rewriting-the-gesta- normannorum-ducum-in-the-fifteenth-century-simon-de-plumetots-brevis-cronica-compendiosa-ducum- normannie/310B7EAF9E26CA8DADF7A6C7EE1B1E23 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ 1 REWRITING THE GESTA NORMANNORUM DUCUM IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY: SIMON DE PLUMETOT’S BREVIS CRONICA COMPENDIOSA DUCUM NORMANNIE* BY BENJAMIN POHL and RICHARD ALLEN This article is dedicated to Liesbeth van Houts, editor of the Gesta Normannorum ducum, generous mentor, colleague, and friend. This article offers an analysis, edition, and translation of the Brevis croniCa Compendiosa ducum Normannie, a historiographical account of the dukes of Normandy and their deeds, written at the turn of the fifteenth century by the Norman jurist and man of letters, Simon de Plumetot (1371–1443). Having all but escaped the attention of modern scholars, this study is the first to examine and publish the Brevis croniCa.