Memorials of Old Suffolk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

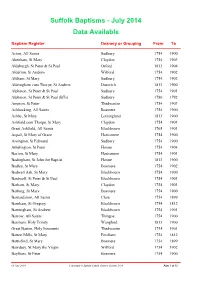

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Fen Management Strategy - Explains the Role of the Strategy and Its Relationship to Other Documents

CONTENTS Acknowledgements Purpose & use of the fen management strategy - explains the role of the strategy and its relationship to other documents Summary - outlines the need for a fen management strategy Introduction - Sets the picture of development and use of fens from their origins to present day Approach to producing strategy - Methodology to writing the fen management strategy Species requirements: This section provides a summary of our existing knowledge concerning birds, plants, mammals and invertebrates associated with the Broads fens. This information forms a basis for the fen management strategy. Vegetation resource Mammals Birds Invertebrates Summary of special features for each valley: This section mainly identifies the botanical features within each valley. The distribution of birds, mammals and invertebrates is either variable or unknown, and so has been covered only in a general sense in the section on species requirements. However, where there is obvious bird interest concentrated within particular valleys, this has been identified. The botanical section provides a summary analysis of the fen vegetation resource survey and considers the relative importance of fen vegetation in a local and national context. A summary of the chemical variables of the soils for each valley has also been included. Ant valley Bure valley Muckfleet valley Thurne valley Waveney valley Yare valley The fen resource for the future: Identifies aims and objectives to restore fens to favourable nature conservation state Environmental constraints and opportunities - Using the fen management strategy: - During the fen vegetation resource survey, chemical variables of the substratum associated with various plant communities were measured. The purpose of these measurements was to provide some indication of the importance of substrate to the plant communities. -

![The Lake Lothing (Lowestoft) Third Crossing Order 201[*]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2933/the-lake-lothing-lowestoft-third-crossing-order-201-102933.webp)

The Lake Lothing (Lowestoft) Third Crossing Order 201[*]

Lake Lothing Third Crossing Chapter 11 of the Environmental Statement R2 - Clean SCC/LLTC/EX/70 The Lake Lothing (Lowestoft) Third Crossing Order 201[*] _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ Document SCC/LLTC/EX/70: Chapter 11 of the Environmental Statement R2 – Clean ________________________________________________________________________ Planning Act 2008 The Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 PINS Reference Number: TR010023 Author: Suffolk County Council Document Reference: SCC/LLTC/EX/70 Date: 29 January 2019 Lake Lothing Third Crossing Chapter 11 of the Environmental Statement R2 - Clean SCC/LLTC/EX/70 This page is intentionally left blank Lake Lothing Third Crossing Chapter 11 of the Environmental Statement - tracked Document Reference: SCC/LLTCEX/27 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 Nature Conservation Scope of the Assessments Introduction This updated chapter 11 of the Environmental Statement describes the assessment of the likely significant effects of the Scheme on biodiversity and nature conservation during the construction and operational. It is supported by Figures 11.1 to 11.7 (APP-150) and Appendices 11A to 11G (APP-183 to APP- 189). The assessment of this topic area considers potential impacts relating to the following aspects: • Statutory and non-statutory designated sites; • Important or protected habitats; and • Legally protected species and/or species of conservation importance. The assessment has incorporated the comments of the Secretary of State (SoS) presented in the Scoping Opinion included in Appendix 6B, as well as those received during the S42 consultation. The assessment should be read in conjunction with Chapter 8: Air Quality; Chapter 12: Geology and Soils, Chapter 13: Noise and Vibration, Chapter 17: Road Drainage and the Water Environment and Chapter 19: Traffic and Transport. -

Awalkthroughblythburghvi

AA WWAALLKK tthhrroouugghh BBLLYYTTHHBBUURRGGHH VVIILLLLAAGGEE Thiis map iis from the bookllet Bllythburgh. A Suffollk Viillllage, on salle iin the church and the viillllage shop. 1 A WALK THROUGH BLYTHBURGH VILLAGE Starting a walk through Blythburgh at the water tower on DUNWICH ROAD south of the village may not seem the obvious place to begin. But it is a reminder, as the 1675 map shows, that this was once the main road to Blythburgh. Before a new turnpike cut through the village in 1785 (it is now the A12) the north-south route was more important. It ran through the Sandlings, the aptly named coastal strip of light soil. If you look eastwards from the water tower there is a fine panoramic view of the Blyth estuary. Where pigs are now raised in enclosed fields there were once extensive tracts of heather and gorse. The Toby’s Walks picnic site on the A12 south of Blythburgh will give you an idea of what such a landscape looked like. You can also get an impression of the strategic location of Blythburgh, on a slight but significant promontory on a river estuary at an important crossing point. Perhaps the ‘burgh’ in the name indicates that the first Saxon settlement was a fortified camp where the parish church now stands. John Ogilby’s Map of 1675 Blythburgh has grown slowly since the 1950s, along the roads and lanes south of the A12. If you compare the aerial view of about 1930 with the present day you can see just how much infilling there has been. -

To Blythburgh, an Essay on the Village And

AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) Alan Mackley Blythburgh 2020 AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) INTRODUCTION Margaret Janet Becker (1904-1953) was the daughter of Harry Becker, painter of the farming community and resident in the Blythburgh area from 1915 to his death in 1928, and his artist wife Georgina who taught drawing at St Felix school, Southwold, from 1916 to 1923. Janet appears to have attended St Felix school for a while and was also taught in London, thanks to a generous godmother. A note-book she started at the age of 19 records her then as a London University student. It was in London, during a visit to Southwark Cathedral, that the sight of a recently- cleaned monument inspired a life-long interest in the subject. Through a friend’s introduction she was able to train under Professor Ernest Tristram of the Royal College of Art, a pioneer in the conservation of medieval wall paintings. Janet developed a career as cleaner and renovator of church monuments which took her widely across England and Scotland. She claimed to have washed the faces of many kings, aristocrats and gentlemen. After her father’s death Janet lived with her mother at The Old Vicarage, Wangford. Janet became a respected Suffolk historian. Her wide historical and conservation interests are demonstrated by membership of the St Edmundsbury and Ipswich Diocesan Advisory Committee on the Care of Churches, and she was a Council member of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. -

Impersonal Style and the Form of Experience in W. G. Sebald's the Rings of Saturn

Please do not remove this page Impersonal Style and the Form of Experience in W. G. Sebald's The Rings of Saturn Persson, Torleif https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643388260004646?l#13643534940004646 Persson, T. (2016). Impersonal Style and the Form of Experience in W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. Studies in the Novel, 48(2), 205–222. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3B56MZ6 This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/27 14:06:53 -0400 Studies in the Novel ISSN 0039-3827 205 Vol. 48 No. 2 (Summer), 2016 Pages 205–222 IMPERSONAL STYLE AND THE FORM OF EXPERIENCE IN W. G. SEBALD’S THE RINGS OF SATURN TORLEIF PERSSON The prose fiction of W. G. Sebald exhibits a curious flatness. The source of this defining quality is what the narrator of The Emigrants calls the “wrongful trespass” of empathetic or emotional identification with the victims of historical calamity (29). The resulting narrative distance is a familiar hallmark of Sebald’s style, realized in his writing through an almost seamless intermingling of fact, fiction, allusion, and recall—a “literary monism”—that fuses different narrative temporalities, superimposes the global on the local, and assimilates a wide range of source materials and intertextual content (McCulloh 22). Two broad responses might be discerned in respect to this particular aspect of Sebald’s writing. The first questions the ethical commitment of a style that is unable to make any kind of moral distinction. -

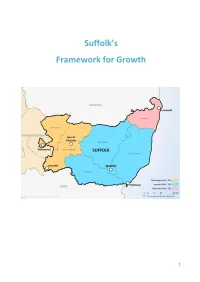

Suffolk's Framework for Growth

Suffolk’s Framework for Growth 1 Foreword Suffolk’s local authorities are working together to address our residents and businesses’ future needs and deliver our growth plans in an inclusive and integrated way. Responding to the Government’s ambitions to increase the nation’s overall prosperity and recognising past growth has not always benefitted all communities equally, our Framework sets out how we will utilise Suffolk’s potential to ensure we plan and achieve the growth that is right for us and our communities. A Framework provides a mechanism to bring together work across teams; including local planning, economic development, skills, and housing; alongside our partners at the University of Suffolk, Suffolk Chamber of Commerce and New Anglia LEP. It sets out how we are working across our administrative boundaries and with our key partners to deliver our physical development (homes, employment sites, public and private buildings) in a way that matches our communities’ aspirations for growth and ensures we can match this with the investment in our infrastructure both now and in the future. The Framework includes links where you can find further, more detailed information. It builds on our conversations with Government, our partners and our communities, which started with our proposals for devolution and have been built on through our responses to both the Industrial Strategy and the Housing White Paper. It will provide the mechanism for monitoring our successes and realigning work that is not achieving the outcomes we anticipate. This Framework has been agreed by all Suffolk Local Authority Leaders and the joint Suffolk Growth Portfolio Holders (GP/H). -

NEWS Letter Autumn 2015 'SEEK the COMMON GOOD' Flooding Problem on Page

Rushmere St Andrew Parish Council NEWS LETTER AUTUMN 2015 'SEEK THE COMMON GOOD' Flooding problem On page . 2 Our new Councillors 2 Have you a Community in The Street not yet Project in mind? 4 Bus Service changes solved satisfactorily 6 Getting yourself into fitness mode We wish we could write on a more the constant flooding of the highway Lawn Cemetery extension positive note however, at the time of close to the entrance to the ITFC 7 writing this article, (early September), Training Ground in Playford Road. taking shape issues of flooded roads in the Parish are I think it’s fair to say that because 8 Update on the Redecroft still with us. To say we are disappointed there are so many similar situations Development is an understatement! across the region, unless people and/ or property are directly affected or 9 Kesgrave Community Let’s first deal with locations other likely to be in danger then there is no Library than the Limes and Chestnut Ponds. real priority to clear these floods. We know of several places where, after 11 Police report a heavy downpour, the water sits on Although there is a maintenance the road. These include, for example, regime in place to clear roadside drains, in many cases the machine Likewise, the problem at the Limes Playford Road and parts of Rushmere Pond where, once again, it would appear Street by the Parish Church. only attends once every nine months or so. It is our belief that this schedule that the lack of maintenance of the There appears to be an ‘impasse’ is not frequent enough for locations drains in the highway is the cause of between the County Council and where there is a build-up of silt and the flooding there. -

1. Parish: Chillesford

1. Parish: Chillesford Meaning: Gravel ford (Ekwall) 2. Hundred: Plomesgate Deanery: Orford ( -1914), Wilford (1914-1972), Woodbridge (1972-) Union: Plomesgate RDC/UDC: (E. Suffolk) Plomesgate RD (1894-1934), Deben RD (1934-1974), Suffolk Coastal DC (1974- ) Other administrative details: Woodbridge Petty Sessional Division and County Court District 3. Area: 1,850 acres land, 2 acres water, 4 acres tidal water, 16 acres foreshore (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a) Deep well drained sandy often ferruginous soils, risk wind and water erosion b) Deep stoneless calcareous/non calcareous clay soils localized peat, flat land, risk of flooding 5. Types of farming: 1500–1640 Thirsk: Problems of acidity and trace element deficiencies. Sheep-corn region, sheep main fertilizing agent, bred for fattening, barley main cash crop 1804 Young: “This corner of Suffolk practices better husbandry than elsewhere” … identified as carrot growing region 1818 Marshall: Management varies with condition of sandy soils. Rotation usually turnip, barley, clover, wheat or turnips as preparation for corn and grass 1937 Main crops: Barley, oats Mainly arable/dairying region 1969 Trist: Dairying has been replaced by arable farming 6. Enclosure: 1 7. Settlement: 1958 Butley river forms part of SW boundary. Tunstall wood intrudes quite extensively into northern sector of parish and Wantisden Heath intrudes into western sector. Small dispersed settlement. Church situated to west of development. Few scattered farms Inhabited houses: 1674 – 3, 1801 – 15, 1851 – 43, 1871 – 48, 1901 – 46, 1951 – 54, 1981 – 48 8. Communications: Road: Roads to Tunstall, Orford and Butley 1912 Carriers pass through from Orford to Woodbridge daily (except Wednesday) Carriers pass through to Ipswich Wednesday and Saturday Rail: 1891 5½ miles Wickham Market station: Ipswich – Lowestoft line, opened (1859), still operational Water: River Butley: formerly navigable (circa 1171). -

1. Parish: Stratford St. Andrew

1. Parish: Stratford St. Andrew Meaning: Ford by which Roman Road crossed river 2. Hundred: Plomesgate Deanery: Orford (−1914), Saxmundham (1914−) Union: Plomesgate RDC/UDC: (E. Suffolk) Plomesgate R.D. (1894−1934), Blyth R.D. (1934−1974), Suffolk Coastal D.C. (1974−) Other administrative details: Framlingham Petty Sessional Division Framlingham and Saxmundham County Court District 3. Area: 800 acres (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a. Deep well drained sandy soils, some very acid, risk wind erosion b. Slowly permeable, seasonally waterlogged, some calcareous, clay and fine loams over clay soils c. Deep fine loam soils with slowly permeable subsoils, slight seasonal waterlogging, similar fine/coarse loam over clay soils d. Some deep peat soils associated with clay over sandy soils, high groundwater levels, risk of flooding by river 5. Types of farming: 1086 8 acres meadow, 2 cattle, 15 pigs, 30 sheep, 27 goats, 1 mill 1500–1640 Thirsk: Sheep-corn region where sheep are main fertilizing agent, bred for fattening. Barley main cash crop. Also has similarities with wood−pasture region with pasture, meadow, dairying and some pig keeping 1818 Marshall: Wide variations of crop ad management techniques including summer fallow in preparation for corn and rotation of turnip, barley, clover, wheat on lighter lands 1937 Main crops: Wheat, roots, barley, hay 1969 Trist: More intensive cereal growing and sugar beet 6. Enclosure: 1 7. Settlement: 1975 River Alde forms natural boundary to NE. Small compact development around central church. Few scattered farms. Inhabited houses: 1674 – 14, 1801 – 21, 1851 – 44, 1871 – 45, 1901 – 41, 1951 – 58, 1981 – 58 8. -

Suffolk County Council

Suffolk County Council Western Suffolk Employment Land Review Final Report May 2009 GVA Grimley Ltd 10 Stratton Street London W1J 8JR 0870 900 8990 www.gvagrimley.co.uk This report is designed to be printed double sided. Suffolk County Council Western Suffolk Employment Land Review Final Report May 2009 Reference: P:\PLANNING\621\Instruction\Clients\Suffolk County Council\Western Suffolk ELR\10.0 Reports\Final Report\Final\WesternSuffolkELRFinalReport090506.doc Contact: Michael Dall Tel: 020 7911 2127 Email: [email protected] www.gvagrimley.co.uk Suffolk County Council Western Suffolk Employment Land Review CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1 2. POLICY CONTEXT....................................................................................................... 5 3. COMMERCIAL PROPERTY MARKET ANALYSIS.................................................... 24 4. EMPLOYMENT LAND SUPPLY ANALYSIS.............................................................. 78 5. EMPLOYMENT FLOORSPACE PROJECTIONS..................................................... 107 6. BALANCING DEMAND AND SUPPLY .................................................................... 147 7. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS......................................................... 151 Suffolk County Council Western Suffolk Employment Land Review LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1 The Western Suffolk Study Area 5 Figure 2 Claydon Business Park, Claydon 26 Figure 3 Industrial Use in -

Records Relating to the 1939 – 1945 War

Records Relating to the 1939 – 1945 War This is a list of resources in the three branches of the Record Office which relate exclusively to the 1939-1945 War and which were created because of the War. However, virtually every type of organisation was affected in some way by the War so it could also be worthwhile looking at the minute books and correspondence files of local councils, churches, societies and organisations, and also school logbooks. The list is in three sections: Pages 1-10: references in all the archive collections except for the Suffolk Regiment archive. They are arranged by theme, moving broadly from the beginning of the War to its end. Pages 10-12: printed books in the Local Studies collections. Pages 12-21: references in the Suffolk Regiment archive (held in the Bury St Edmunds branch). These are mainly arranged by Battalion. (B) = Bury Record Office; (I) = Ipswich Record Office; (L) = Lowestoft Record Office 1. Air Raid Precautions and air raids ADB506/3 Letter re air-raid procedure, 1940 (B) D12/4/1-2 Bury Borough ARP Control Centre, in and out messages, 1940-1945 (B) ED500/E1/14 Hadleigh Police Station ARP file, 1943-1944 (B) EE500/1/125 Bury Borough ARP Committee minutes, 1935-1939 (B) EE500/33/17/1-7 Bury Town Clerk’s files, 1937-1950 (B) EE500/33/18/1-6 Bury Town Clerk’s files re Fire Guard, 1938-1947 (B) EE500/44/155-6 Bury Borough: cash books re Government Shelter scheme (B) EE501/6/142-147 Sudbury Borough ARP registers, report books and papers, 1938-1945 (B) EE501/8/27(323, Plans of air-raid shelters, Sudbury,