Notes and Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three Minor Revisions

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2001 The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions John Donald Hosler Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Hosler, John Donald, "The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions" (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 21277. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/21277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions by John Donald Hosler A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Major Professor: Kenneth G. Madison Iowa State University Ames~Iowa 2001 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of John Donald Hosler has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 The liberal arts had not disappeared, but the honours which ought to attend them were withheld Gerald ofWales, Topograhpia Cambria! (c.1187) IV TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION 1 Overview: the Reign of Henry II of England 1 Henry's Conflict with Thomas Becket CHAPTER TWO. -

King John in Fact and Fiction

W-i".- UNIVERSITY OF PENNS^XVANIA KING JOHN IN FACT AND FICTION BY RUTH WALLERSTEIN ff DA 208 .W3 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARY ''Ott'.y^ y ..,. ^..ytmff^^Ji UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA KING JOHN IN FACT AND FICTION BY RUTH WAIXE510TFIN. A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GiLA.DUATE SCHOOL IN PARTLVL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 'B J <^n5w Introductory LITTLE less than one hundred years after the death of King John, a Scottish Prince John changed his name, upon his accession to L the and at the request of his nobles, A throne to avoid the ill omen which darkened the name of the English king and of John of France. A century and a half later, King John of England was presented in the first English historical play as the earliest English champion and martyr of that Protestant religion to which the spectators had newly come. The interpretation which thus depicted him influenced in Shakespeare's play, at once the greatest literary presentation of King John and the source of much of our common knowledge of English history. In spite of this, how- ever, the idea of John now in the mind of the person who is no student of history is nearer to the conception upon which the old Scotch nobles acted. According to this idea, John is weak, licentious, and vicious, a traitor, usurper and murderer, an excommunicated man, who was com- pelled by his oppressed barons, with the Archbishop of Canterbury at their head, to sign Magna Charta. -

King John's Tax Innovation -- Extortion, Resistance, and the Establishment of the Principle of Taxation by Consent Jane Frecknall Hughes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eGrove (Univ. of Mississippi) Accounting Historians Journal Volume 34 Article 4 Issue 2 December 2007 2007 King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent Jane Frecknall Hughes Lynne Oats Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Jane Frecknall and Oats, Lynne (2007) "King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 34 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol34/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hughes and Oats: King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent Accounting Historians Journal Vol. 34 No. 2 December 2007 pp. 75-107 Jane Frecknall Hughes SHEFFIELD UNIVERSITY MANAGEMENT SCHOOL and Lynne Oats UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK KING JOHN’S TAX INNOVATIONS – EXTORTION, RESISTANCE, AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PRINCIPLE OF TAXATION BY CONSENT Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to present a re-evaluation of the reign of England’s King John (1199–1216) from a fiscal perspective. The paper seeks to explain John’s innovations in terms of widening the scope and severity of tax assessment and revenue collection. -

Anglo-Norman Views on Frederick Barbarossa and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa Citation for published version: Raccagni, G 2014, 'English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa' Quaderni Storici, vol. 145, pp. 183-218. DOI: 10.1408/76676 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1408/76676 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaderni Storici Publisher Rights Statement: © Raccagni, G. (2014). English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. Quaderni Storici, 145, 183-218. 10.1408/76676 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick Barbarossa* [A head]Introduction In the preface to his edition of the chronicle of Roger of Howden, William Stubbs briefly noted how well English chronicles covered the conflicts between Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and the Lombard cities.1 Unfortunately, neither Stubbs nor his * I wish to thank Bill Aird, Anne Duggan, Judith Green, Elisabeth Van Houts and the referees of Quaderni Storici for their suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this work. -

Converted by Filemerlin

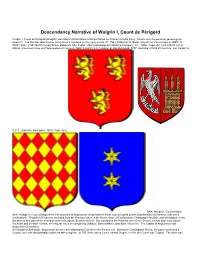

Descendancy Narrative of Wulgrin I, Count de Périgord Wulgrin I, Count de Périgord (Wulgrin I was Mayor of the Palace of King Charles Le Chauve) (André Roux: Scrolls from his personal genealogicaL research. The Number refers to the family branch numbers on his many scrolls, 87, 156.) (Roderick W. Stuart, Royalty for Commoners in ISBN: 0- 8063-1344-7 (1001 North Calvert Street, Baltimore, MD 21202, USA: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc., 1992), Page 234, Line 329-38.) (P.D. Abbott, Provinces, Pays and Seigneuries of France in ISBN: 0-9593773-0-1 (Author at 266 Myrtleford, 3737, Australia: Priries Printers Pty. Ltd, Canberra A.C.T., Australia, November, 1981), Page 329.). AKA: Wulgrin I, Count d'Agen. AKA: Wulfgrin I, Count d'Angoulême The province of Angoumois comprised the areas now occupied by the Departments of Charente, with some rectifications. Regions of Charente excluded from the Province were, in the North, those of Confolentais, Champagne Mouton, and Villelagnon; in the Southwest, that part of the arrondissement of Cognac, South of the Né. But included in the Province were Deux Sèvres, a small pays near Sauzé- Vaussais and in Haute Vienne, an irregular intrusion comprising Oradour, Saint Mathieu, and Saint Victurnien. The Capital of Angoumois was Angoulême [Charente]. At first part of Saintonge, Angoumois became an independent City late in the Roman era. During the Carolingians Period, the pays constituted a County, as it was also probably under the Mérovingiens. In 770, there was a Comte named Vulgrin; in 839, the Comte was Turpion. The latter was killed by Normans in 863. -

King John and Arthur of Brittany

1909 659 Downloaded from King John and Arthur of Brittany FTER studying, in the order of their composition, the authori- ties which refer to or discuss the death of Arthur and the http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ Aalleged condemnation of King John by his peers in the French court, I have been led to feel considerable doubt concerning the orthodox view on the subject. That view is the negative con- clusion reached by M. Bemont in his well-known thesis nearly a quarter of a century ago. With one important exception—M. Guilhiermoz—every scholar who has gone over the evidence since M. B6mont published his thesis, has agreed with the master.1 And, indeed, every student of the period must feel that his opinion, at University of Tennessee ? Knoxville Libraries on August 19, 2015 whatever it may be, owes almost everything to the preliminary collection and criticism of the evidence by M. Bemont. In the following pages I haye not hesitated to leave unnoticed a good deal of the discussion, including the juridical arguments of M. Guilhiermoz. I have simply reviewed the evidence in the order, first, in which it became known to contemporaries, and secondly, of its composition. The chief conclusions at which the paper arrives may be thus summarised, in addition to the fact that no con- temporary official documents before those of 1216 refer to the con- demnation of King John :— 1. There was no certainty in contemporary knowledge of how Arthur died, but it does not follow that John was not condemned. What evidence there is, apart from the chronicle of Margam, goes to show that he was condemned, rather than the reverse. -

Crusades, Martyrdoms, and the Jews of Norman England, 1096-1190

Crusades, Martyrdoms, and the Jews of Norman England, 1096-1190 BY ROBERT C. STACEY A connection between crusading and anti-Jewish violence was forged in 1096, first in northern France, and then, most memorably, in the cataclysmic events of the Rhineland. Thereafter, attacks on Jews and Jewish communities became a regulär feature of the cru sading movement, despite the efforts of ecclesiastical and secular authorities to prevent them. The Second Crusade saw renewed assaults in the Rhineland and northern France. In the Third Crusade, assaults in the Rhineland recurred, but the worst violence this time oc curred in England, where something on the order of 10% of the entire Jewish Community in England perished in the massacres of 11891190. After the 1190s, however, direct mob violence by crusaders against Jews lessened. Although Crusades would continue to pro voke antiJewish hostility, no further armed assaults on Jewish communities, on the scale of those that took place between 1096 and 1190, would accompany the thirteenth Century 1 Crusades ^. The connection we are attempting to explain, between crusading and armed at tacks on Jewish communities, is thus distinctly a phenomenon of the twelfth Century provided, of course, that we may begin our twelfth Century in 1096. Attempts to analyze this connection between crusading and antiJewish assaults have generally focused on the First Crusade. This is understandable, and by no means misguid ed. Thanks to the work of Jonathan RileySmith, Robert Chazan, Jeremy Cohen, Yisrael Yuval, Ivan Marcus, Kenneth Stow and others, we now understand far more about the background, nature, and causes of the events of 1096 than we did a generation ago. -

Some Aspects of the History of Barnwell Priory: 1092-1300

SOME ASPECTS OF THE HISTORY OF BARNWELL PRIORY: 1092-1300 JACQUELINE HARMON A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNIVERSITY OF EAST ANGLIA SCHOOL OF HISTORY SEPTEMBER 2016 Contents Abstract iii Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations v-vi Maps vii Tables viii Figures viiii 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography 6 3. Harleian 3601: The Liber Memorandorum 29 The Barnwell Observances 58 Record Keeping at Ely 74 Chronicles of local houses contemporary with the Liber 76 4. Scribal Activity at Barnwell 80 Evidence for a Library and a Scriptorium 80 Books associated with the Priory 86 The ‘Barnwell Chronicle’ 91 The Role of the Librarian/Precentor 93 Manuscript production at Barnwell 102 5. Picot the Sheriff and the First Foundation 111 Origins and Identity 113 Picot, Pigot and Variations 115 The Heraldic Evidence 119 Genealogy and Connections 123 Domesday 127 Picot and Cambridge 138 The Manor of Bourn 139 Relations with Ely 144 The Foundation of St Giles 151 Picot’s Legacy 154 i 6. The Peverels and their Descendants 161 The Peverel Legend 163 The Question of Co-Identity 168 Miles Christi 171 The Second Foundation 171 The Descent of the Barony and the Advowson of Burton Coggles 172 Conclusion 178 7. Barnwell Priory in Context 180 Cultural Exchange in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries 180 The Rule of St Augustine 183 Gregorian Reform and the Eremetical Influence 186 The Effects of the Norman Conquest 190 The Arrival of the Canons Regular in England 192 The Early Houses 199 The Hierarchy of English Augustinian Houses 207 The Priory Site 209 Godesone and the Relocation of the Priory 212 Hermitages and Priories 214 8. -

Notes and Documents Downloaded from the Letters of Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine to Pope Celestine III

78 LETTERS OF ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE Jan. Notes and Documents Downloaded from The Letters of Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine to Pope Celestine III. OP all the perils which beset the unwary historian none is more insidious than the rhetorical exercise masquerading in the guise of http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ an historical letter; it deceives only the more effectually because it was written with no thought of deception, and is often close enough to fact and accurate enough in form to mislead all but the most minute and laborious of critics. The present article is an attempt to follow up the suggestion of M. Charles Bemont that the three letters from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Pope Celestine III, printed by Eymer in the Foedera, are rhetorical studies of this nature. at Emory University on August 24, 2015 The letters in question purport to be addressed by Queen Eleanor to the pope, imploring his intervention on behalf of her son, Richard I, then a prisoner in the hands of the emperor Henry VI. Not only has their authenticity been accepted without question, but bibliographers have derived from them Eleanor's title to a place in the company of royal and noble authors,1 while historians have built up on them a theory of the part played by the queen mother in the release of the captive king. Finding the letters to Celestine HI under Eleanor's name, the modern historians of the twelfth century have connected them with a state- ment made by Roger of Hoveden to the effect that in the year 1198 the pope wrote to the clergy of England, ut imperator et totvm ipsius regnum subiicerentur anathemati, nisi rex Angliae celerius liberaretur a eaptione iltixw.* The editors of the Recueil des Historiens de France * mention Eleanor's letters and then quote Hoveden, leaving the connexion to be inferred. -

The Feast of Saint Thomas Becket at Salisbury Cathedral: Ad Vesperas

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2019 The Feast of Saint Thomas Becket at Salisbury Cathedral: Ad Vesperas Virginia Elizabeth Martin Tilley College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Tilley, Virginia Elizabeth Martin, "The Feast of Saint Thomas Becket at Salisbury Cathedral: Ad Vesperas" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1385. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1385 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Feast of Saint Thomas Becket at Salisbury Cathedral: Ad Vesperas A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Music from The College of William and Mary by Virginia Elizabeth Martin Tilley Accepted for __________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Thomas B. Payne, Director, Music ________________________________________ James I. Armstrong, Music ________________________________________ Alexander B. Angelov, Religious Studies Williamsburg, VA 12 April -

Accepted Manuscript

English (and European) Royal Charters: from Reading to reading Nicholas Vincent University of East Anglia What follows was first delivered as a lecture ‘off the cuff’ in November 2018, in circumstances rather different from those in which, writing this in January 2021, I now set down an extended text. In the intervening two and a bit years, Brexit has come, and gone. The Covid virus has come, but shows no immediate sign of going. When I lectured in 2018, although the edition of The Letters and Charters of King Henry II was in press, the publishers were still working to produce proofs. These were eventually released in December 2019, ensuring that I spent the entire period of Covid lockdown, from March to December 2020 correcting and re-correcting 4,200 proof pages. The first 3,200 of these were published, in six stout volumes, at the end of December 2020.1 A seventh volume, of indexes, should appear in the spring of 2021, leaving an eighth volume, the ‘Introduction’, for completion and publication later this year. All told, these eight volumes assemble an edition of 4,640 items, derived from 286 distinct archival repositories: the largest such assembly of materials ever gathered for a twelfth-century king not just of England but of any other realm, European or otherwise. In a lecture delivered at the University of Reading, as a part of a symposium intended to honour one of Reading’s more distinguished former professors, I shall begin with the debt that I and the edition owe to Professor Sir James (henceforth ‘Jim’) Holt.2 It was Jim, working from Reading in the early 1970s, who struck the spark from which this great bonfire of the vanities was lit. -

![Accounting Historians Journal, 2007, Vol. 34, No. 2 [Whole Issue]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6983/accounting-historians-journal-2007-vol-34-no-2-whole-issue-3586983.webp)

Accounting Historians Journal, 2007, Vol. 34, No. 2 [Whole Issue]

Accounting Historians Journal Volume 34 Article 11 Issue 2 December 2007 2007 Accounting Historians Journal, 2007, Vol. 34, no. 2 [whole issue] Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation (2007) "Accounting Historians Journal, 2007, Vol. 34, no. 2 [whole issue]," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 34 : Iss. 2 , Article 11. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol34/iss2/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Accounting Historians Journal, 2007, Vol. 34, no. 2 Published by eGrove, 2007 1 Accounting Historians Journal, Vol. 34 [2007], Iss. 2, Art. 11 Published by The Academy of Accounting Historians The Praeterita Illuminant Postera Accounting Historians Journal The Accounting Historians Journal V ol. 34, No. 2 December 2007 Volume 34, Number 2 DECEMBER 2007 Research on the Evolution of Accounting Thought and Accounting Practice https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol34/iss2/11 2 et al.: Accounting Historians Journal, 2007, Vol. 34, no. 2 The Accounting Historians Journal THE ACADEMY OF ACCOUNTING HISTORIANS Volume 34, Number 2 December 2007 APPLICATION FOR 2007 MEMBERSHIP 2007 OFFICERS Individual Membership: $45.00 President Vice-President - Partnerships Student Membership: $10.00 Stephen Walker Barry Huff Cardiff University Deloitte & Touche PH: 44-29-2087-4000 PH: 01-412-828-3852 FAX: 44-29-2087-4419 FAX: 01-412-828-3853 Name: (please print) email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Mailing Address: President-Elect Secretary Hiroshi Okano Stephanie D.