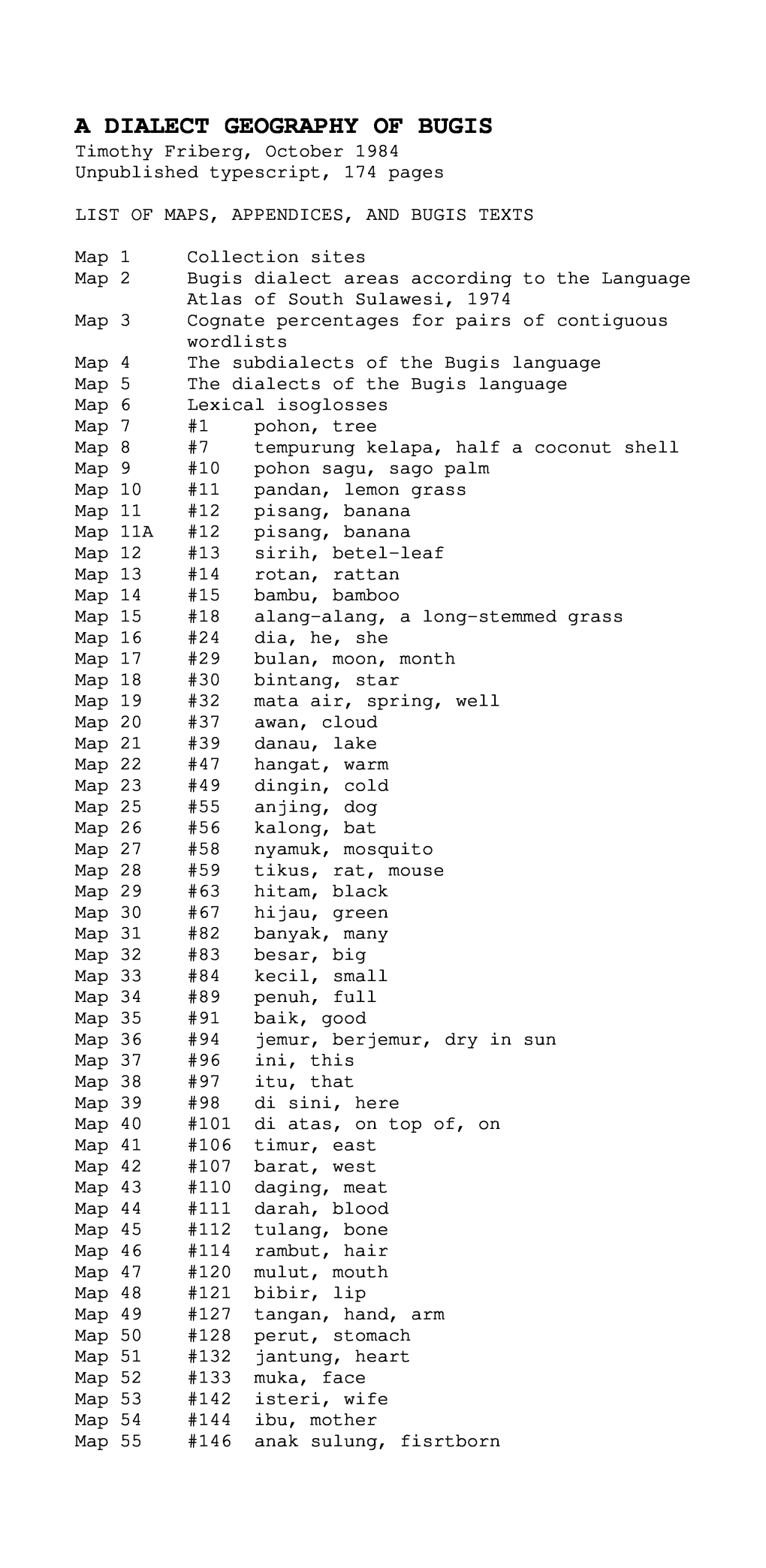

A DIALECT GEOGRAPHY of BUGIS Timothy Friberg, October 1984 Unpublished Typescript, 174 Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Languages in Indonesia Volume 49, 2001

ISSN 0126 2874 NUSA LINGUISTICS STUDIES OF INDONESIAN AND OTHER LANGUAGES IN INDONESIA VOLUME 49, 2001 e It lie I 1414 ' 4 0:1111111 4.11.114114" .M4 • 16700' 4 at" STUDIES IN SULAWESI LINGUISTICS PART VII Edited by Wyn D. Laidig STUDIES IN SULAWESI LINGUISTICS PART VII NUSA Linguistic Studies of Indonesian and Other Languages in Indonesia Volume 49, 2001 EDITORS: S oenjono Dardj owidjoj o, Jakarta Bambang Kaswanti Purwo, Jakarta Anton M. Mo e li on o, Jakarta Soepomo Poedjosoedarmo, Yogyakarta ASSISTANT EDITOR: Yassir Nassanius ADDRESS: NUSA Pusat Ka,jian Bahasa dan Budaya Jalan Jenderal Sudirtnan 51 Ko tak Pos 2639/At Jakarta 12930, Indonesia Fax (021) 571-9560 Email: [email protected],id All rights reserved (see also information page iv) ISSh? 0126 - 2874 11 EDITORIAL The present volume is the forty seventh of the Series NUM, Swdie.s in Sulawesi Languages, Part VI. The Series focuses on works about Indonesian and other languages in Indonesia. Malaysian and the local dialects of Malay wilt be accepted, but languaga outside these regions will be considered only In so far as they are theoretically relevant to our languages. Reports from field work in the form of data analysis or texts with translation, book reviews, squibs and discussions are also accepted. Papers appearing in NUSA can be original or traiislated from languages other than English. Although our main interest is restricted to the area of Indonesia, we welcome works on general linguistics that can throw light upon problems that we might face. It is hoped that NUS, can be relevant beyond the range of typological and area specializations and at the same time also serve the cause of deoccidentaliation of general linguistics. -

Spices from the East: Papers in Languages of Eastern Indonesia

Sp ices fr om the East Papers in languages of eastern Indonesia Grimes, C.E. editor. Spices from the East: Papers in languages of Eastern Indonesia. PL-503, ix + 235 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2000. DOI:10.15144/PL-503.cover ©2000 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Also in Pacific Linguistics Barsel, Linda A. 1994, The verb morphology of Mo ri, Sulawesi van Klinken, Catherina 1999, A grammar of the Fehan dialect of Tetun: An Austronesian language of West Timor Mead, David E. 1999, Th e Bungku-Tolaki languages of South-Eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia Ross, M.D., ed., 1992, Papers in Austronesian linguistics No. 2. (Papers by Sarah Bel1, Robert Blust, Videa P. De Guzman, Bryan Ezard, Clif Olson, Stephen J. Schooling) Steinhauer, Hein, ed., 1996, Papers in Austronesian linguistics No. 3. (Papers by D.G. Arms, Rene van den Berg, Beatrice Clayre, Aone van Engelenhoven, Donna Evans, Barbara Friberg, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Paul R. Kroeger, DIo Sirk, Hein Steinhauer) Vamarasi, Marit, 1999, Grammatical relations in Bahasa Indonesia Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia, Southeast and South Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. -

Maintenance of Tae' Language by Luwu Minority Living In

MAINTENANCE OF TAE’ LANGUAGE BY LUWU MINORITY LIVING IN MAKASSAR THESIS Submitted to the Adab and Humanities Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement to Obtain A Sarjana Degree in English and Literature Department of Alauddin State Islamic University of Makassar BY SULVIA RUSLI 40300112048 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF MAKASSAR SAMATA-GOWA 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENT Firstly, the researcher would like to express a lot of thanks to Allah SWT for His Blessing, Loving, Opportunity, Health and Mercy, that enables me to finish the prestigious work in my life. Secondly, I would like to say from my deepest of my heart, thanks to prophet Muhammad SAW, for his model and guidance in this life. The researcher realizes that there are many people who have given supports, prays, and encouragement sincerely in order to help the researcher complete this thesis. My greatest thankfulness is also dedicated for my beloved parents Ayah Rusli S.E & Ibu’ ST. Murniati Sambopadang. You are my everything, my inspiration, spirit, and my love that always make my life so wonderful. I love you so much. I also say thank to my sisters Mutiara Wulansari, Trya Febriyanti, Ifa Musdalifa, and my young single brother Muh. Muchlis R, that always support me, always loving me, and give me spirit every day. To all of my lovely family, that always give me a laugh, cheer, and supporting me until the end of my study. Therefore, the researcher would like to express his deepest gratitude to the following: 1. I would like express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to my lovely and patient supervisors, Dr. -

Language Shift of Alas Language Among Alas Kids in Southeast Aceh

LANGUAGE SHIFT OF ALAS LANGUAGE AMONG ALAS KIDS IN SOUTHEAST ACEH SKRIPSI Submitted in Particial Fulfilment of the Requiretment For the Degree of Sarjana Pendidikan (S.Pd) English Education Program By: RISNAWATI NPM: 1502050023 FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MUHAMMADIYAH SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 ABSTRACT Risnawati, 1502050023. Language Shift of Alas Language Among Alas Kids in Southeast Aceh. Skripsi : English Department of Faculty Teacher Training and Education, University of Muhammadiyah Sumatera Utara. Medan. 2019. Alukh Nangke village kids often use mixed languages such as the Alas language with Indonesian. The objectives of this study are (1) to find out the use of the Alas language among kids in Alukh Nangke Village, Tanoh Alas Subdistrict (2) To know the factors that influence the shift in Alas language among kids Alukh Nangke Village in Tanoh Alas District. The method used is qualitative research. The research location was in Alukh Nangke Village, Tanoh Alas District, Southeast Aceh Regency. The subjects in this study were 5 kindergarten-level kids and 5 elementary school kids Alukh Nangke Village. The informants in this study were the headman, parents of kids, and the school teacher at Alukh Nangke kids. Data collection techniques used were observation, interviews, documentation. From this study found two factors that influence the shift of the Alas language to Indonesian, namely internal factors and external factors. Internal factors of parents / family and intermarriage factors where both of these can influence the language shift in the Alas language to Indonesian. While external factors are factors from outside these factors can also affect the shifting of the Alas language to Indonesian, where one of the factors is from education / school and the factor of interaction with friends and the surrounding environment. -

Highly Complex Syllable Structure

Highly complex syllable structure A typological and diachronic study Shelece Easterday language Studies in Laboratory Phonology 9 science press Studies in Laboratory Phonology Chief Editor: Martine Grice Editors: Doris Mücke, Taehong Cho In this series: 1. Cangemi, Francesco. Prosodic detail in Neapolitan Italian. 2. Drager, Katie. Linguistic variation, identity construction, and cognition. 3. Roettger, Timo B. Tonal placement in Tashlhiyt: How an intonation system accommodates to adverse phonological environments. 4. Mücke, Doris. Dynamische Modellierung von Artikulation und prosodischer Struktur: Eine Einführung in die Artikulatorische Phonologie. 5. Bergmann, Pia. Morphologisch komplexe Wörter im Deutschen: Prosodische Struktur und phonetische Realisierung. 6. Feldhausen, Ingo & Fliessbach, Jan & Maria del Mar Vanrell. Methods in prosody: A Romance language perspective. 7. Tilsen, Sam. Syntax with oscillators and energy levels. 8. Ben Hedia, Sonia. Gemination and degemination in English affixation: Investigating the interplay between morphology, phonology and phonetics. 9. Easterday, Shelece. Highly complex syllable structure: A typological and diachronic study. ISSN: 2363-5576 Highly complex syllable structure A typological and diachronic study Shelece Easterday language science press Easterday, Shelece. 2019. Highly complex syllable structure: A typological and diachronic study (Studies in Laboratory Phonology 9). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/249 © 2019, Shelece -

BARUGA - Sulawesi Research Bulletin

• V SULAWESI RESEARCH BULLETIN I.. «NW* I e- A 1.r os, ‘4164.4 0.3.-N , ‘C N 0. 2 _ ' ‘ 1. M A Y 1988 v._ AIR _Amore:eV' -- 4°4116b.) _ 4 / 11 f (iiv v44, h. 5. 0-44-1# • • - - r, '-ucc SULAWESI RESEARCH BULLETIN NO2 MAY 1988 1 BARUGA - Sulawesi Research Bulletin The word 'baruga' is found in a number of Sulawesi languages with the common meaning of 'meeting hall'. Editorial note This is the second issue of Baruga; many thanks to those who have contributed to it and 'sorry' to those who will have to wait to see their feats mentioned in the next issue. Although this issue is about three times as thick as the first, there is no reason to be triumphant or content. A lot of new input is needed to keep this project going, but the results so far show that cooperation and some hard work can produce a valuable newsletter. As for the contents, there is a clear bias' towards South Sulawesi, but this may well reflect the present research situation. Efforts towards a more balanced picture are welcome. We are fully aware that we are not as complete as is desirable. In the section 'recent publications' for example, (mostly drawn from Excer to Indonesia) there are probably major omissions. If you know of any, do not hesitate to write to us. All communications worthwhile for Sulawesi specialists are welcome. Contents: I. 'Conference reports p.2 II. Recent publications p.5 III. Work in progress p.7 IV. -

Language Shift and Heritage Language Maintenance Among Indonesian Young Generations: a Case Study of Pamulang University Students

EUFONI: Journal of Language, Literary, and Cultural Studies Vol. 4, No. 1 (2020) LANGUAGE SHIFT AND HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG INDONESIAN YOUNG GENERATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF PAMULANG UNIVERSITY STUDENTS Eka Margianti Sagimin Universitas Pamulang [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to analyze language shift and heritage language maintenance among Indonesian young generation, a case study of Pamulang University students. Based on that purpose, this study conducted some research in analyzing effort to maintain the heritage language, analyzing the strategy used in maintaining heritage language, and identifying factors contribute to language loss among students. The study used a descriptive qualitative research design approach involving an open-ended questionnaire consisted of open-ended questions. The result of this study revealed that even though they live on a small scale of their native community, yet, they can maintain their local language. Thus, it can not be denied that youth people tend to shift the language due to globalization and the embracing of technology. In conclusion, it can be inferred that most students of Unpam use their local language and Bahasa Indonesia at the same level. Many of them still use local language when communicating with their parents and family members around them as well as Bahasa Indonesia. Suek suggested a solution to this problem that the community should be related to the use of language and attitudes in which mostly happen in school and family. It is hoped when children get used to a local language, they will also become aware of how important the native language as showing their identity in their environment and nationality. -

Speech Act of Buginese Housewives in Character-Building of Pre-School Children

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 350-356, March 2015 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0602.15 Speech Act of Buginese Housewives in Character-building of Pre-school Children Hj. Ratnawati Umar Students Graduate Program, State University of Makassar, Indonesia H. Achmad Tolla The Graduate Program, State University of Makassar, Indonesia H. Zainuddin Taha The Graduate Program, State University of Makassar, Indonesia Abdullah Dola The Graduate Program, State University of Makassar, Indonesia Abstract—This research aims to find out and thus explain the form, function, strategy, as well as implication of speech act behavior of Buginese housewives in character-building of pre-school children. The research done using qualitatif method with description design. Data gathered are in terms of act and speech of Buginese housewives in Wajo District. The form of speech act behavior is performed to say the written form of the word, or called performative speech act, to enable the children to understand. The function is described when the teacher converse by observing or asking matters related to the child condition while at school. The function of speech act is illustrated through the communication between teacher and student, by observing or inquiring about the observed condition of the student within the school environment. Additional of particles such as mi, ki and ta at the end of words are used in the conversation, by both teacher and student. The strategy of speech act behavior is meant to have better communication, and thus the simultaneous use of verbal and nonverbal language. -

Master Program in Linguistics, Diponegoro University In

ISSN: 2088-6799 LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AND SHIFT V September 2 3, 2015 Revised Edition Master Program in Linguistics, Diponegoro University in Collaboration with Balai Bahasa Provinsi Jawa Tengah Proceedings International Seminar Language Maintenance and Shift V “The Role of Indigenous Languages in Constructing Identity” September 2 3, 2015 2 1 x 29,7 cmxviii+433 hlm. 21 x 29,7 cmxviii+433 ISSN: 2088-6799 Compiled by: Herudjati Purwoko (Indonesia) Agus Subiyanto (Indonesia) Wuri Sayekti (Indonesia) Tohom Marthin Donius Pasaribu (Indonesia) Yudha Thianto (United States of America) Priyankoo Sarmah (India) Zane Goebel (Australia) Balai Bahasa Provinsi Jawa Tengah Jalan Imam Bardjo, S.H. No.5 Semarang Telp/Fax +62-24-8448717 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mli.undip.ac.id/lamas International Seminar “Language Maintenance and Shift” V September 2-3, 2015 NOTE This international seminar on Language Maintenance and Shift V (LAMAS V for short) is a continuation of the previous LAMAS seminars conducted annually by the Master Program in Linguistics, Diponegoro University in cooperation with Balai Bahasa Provinsi Jawa Tengah. We would like to extent our deepest gratitude to the seminar committee for putting together the seminar that gave rise to this compilation of papers. Thanks also go to the Head and the Secretary of the Master Program in Linguistics Diponegoro University, without whom the seminar would not have been possible. The table of contents lists 92 papers presented at the seminar. Of these papers, 5 papers are presented by invited keynote speakers. They are Prof. Aron Repmann, Ph.D. (Trinity Christian College, USA), Prof. Yudha Thianto, Ph.D. -

INTERFERENCE of LOCAL CULTURE on the USE of INDONESIAN LANGUAGE in SOUTH SULAWESI (Interferensi Budaya Lokal Pada Penggunaan Bahasa Indonesia Di Sulawesi Selatan)

SAWERIGADING Volume 20 No. 2, Agustus 2014 Halaman 261—269 INTERFERENCE OF LOCAL CULTURE ON THE USE OF INDONESIAN LANGUAGE IN SOUTH SULAWESI (Interferensi Budaya Lokal Pada Penggunaan Bahasa Indonesia di Sulawesi Selatan) David G. Manuputty Balai Bahasa Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan dan Provinsi Sulawesi Barat Jalan Sultan Alauddin Km 7/Tala Salapang Makassar 90221 Telepon (0411)882401, Faksimile (0411)882403 Pos-el: [email protected] Diterima: 4 Maret 2014; Direvisi: 7 Juni 2014; Diterima: 14 Juli 2014 Abstrak Selain bahasa Indonesia, ada bahasa daerah dan bahasa asing. Namun, sesuai dengan amanat Undang-Undang Dasar 1945 dan Pasal 36, butir ketiga Sumpah Pemuda, pemerintah berkewajiban untuk mengembangkan dan membina bahasa Indonesia sebagai bahasa nasional dan bahasa daerah, terutama yang dipelihara dan digunakan oleh penuturnya, sebagai salah satu unsur kebudayaan nasional. Tak dapat dipungkiri bahwa bahasa asing dan bahasa daerah banyak memengaruhi bahasa Indonesia. Bahasa asing mewarnai sektor ilmu pengetahuan, teknologi, dan perdagangan, sementara bahasa daerah menginterferensi aspek budaya dan nilai rasa. lnterferensi adalah masuknya kata serapan ke dalam suatu bahasa yang sesungguhnya melanggar kaidah bahasa itu sendiri. Contoh: penggunaan kosakata ‘kita’ yang sebenarnya berarti ‘orang pertama jamak’ dalam bahasa Indonesia; sementara penyebutan ‘kita’ dalam hal ini mengacu pada orang kedua ‘Anda’. Metode yang digunakan dalam penulisan ini adalah deskriptif-kualitatif yang ditunjang oleh teknik pengumpulan data, yaitu menginventarisasi kosakata, klitik, dan struktur bahasa Bugis dan bahasa Makassar. Bagaimanakah fenomena budaya, terutama bahasa daerah, di Sulawesi Selatan menginterferensi penggunaan bahasa Indonesia? Hal-hal inilah yang menjadi parameter dalam penulisan ini. Kata kunci: bahasa Indonesia, bahasa daerah, interferensi Abstract In addition to Indonesian language, there are local languages and foreign languages. -

162 Influenced Factors Towards the Language Shift

Kajian Linguistik dan Sastra, Vol 25, No 2, Desember 2013, 162-192 INFLUENCED FACTORS TOWARDS THE LANGUAGE SHIFT PHENOMENON OF WOTUNESE Masruddin STAIN Palopo [email protected] ABSTRACT This study aims to find out the factors influence on the language shift of Wotunese. This study was carried out in two villages namely Lampenai Village and Bawalipu Village, Wotu District, East Luwu Regency. The method used was field survey by distributing questionnaire, interviewing and direct observation for 400 Wotunese, interview the informant sample comprised 400 males and females of Wotunese who live in Wotu area at least 10 years. Their ages are around 10 up to 50 years old. The results show that the determinant factors influence significantly on language shift of Wotunese are age, mobilization, bilingualism and language attitude. Then, the government and the wotunese should do some real actions to save Wotu language from the death language phenomenon. Key words: Language shift, Wotunese, Determinant Factors ABSTRAK Tujuan penelitian ini adalah untuk mengetahui faktor-faktor yang mempengaruhi pergeseran bahasa Wotu. Penelitian ini dilaksanakan di dua desa yakni Desa Lampenai dan Desa Bawalipu Kecamatan Wotu Kabupaten Luwu Timur. Metode yang digunakan adalah metode survei lapangan dengan membagikan angket, wawancara, dan pengamatan langsung terhadap 400 warga masyarakat Wotu. Ke- 400 informan tersebut terdiri dari pria dan wanita yang telah tinggal minimal 10 tahun di daerah Wotu. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa pergeseran bahasa Wotu sangat dipengaruhi oleh usia, tingkat mobilisasi, kedwibahasaan, dan sikap bahasa. Selanjutnya, pemerintah dan masyarakat Wotu haruslah melakukan tindakan nyata untuk menghindarkan bahasa Wotu dari peristiwa kematian bahasa. Kata kunci: Pergeseran Bahasa, Masyarakat Wotu, Faktor Penyebab Introduction (Bathula, 2004). -

Open Access College of Asia and the Pacific the Australian National University

Open Access College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Papers from 12-ICAL, Volume 3 Malcolm D. Ross and I Wayan Arka (eds.) A-PL 018 / SAL 004 This volume contains papers describing and discussing language change in the Austronesian languages of eastern Indonesia and Taiwan. The issues discussed include the unusual development of verbal infixes in the Cendrawasih Bay languages, dialect variations, patterns of borrowing and language contact in Taiwan and in Flores-Alor-Pantar languages of Indonesia, diachronic and synchronic aspects of voice systems of Sulawesi languages, and the reconstruction of Proto Austronesian personal pronouns. This volume should be of interest to Austronesianists and historical linguists. Asia-Pacific Linguistics SAL: Studies on Austronesian Languages EDITORIAL BOARD: I Wayan Arka, Mark Donohue, Bethwyn Evans, Nicholas Evans,Simon Greenhill, Gwendolyn Hyslop, David Nash, Bill Palmer,Andrew Pawley, Malcolm Ross, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson. Published by Asia-Pacific Linguistics College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Canberra ACT 2600 Australia Copyright is vested with the author(s) First published: 2015 URL: http://hdl.handle.net/1885/13386 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Language Change in Austronesian languages: papers from 12-ICAL, Volume 3 / edited by Malcolm D. Ross and I Wayan Arka ISBN: 9781922185198 (ebook) Series: Asia-Pacific linguistics 018 / Studies on Austronesian languages 004 Subjects: Austronesian languages--Congresses. Dewey Number: 499.2 Other Creators/Contributors: Ross, Malcolm D., editor. Arka, I Wayan, editor. Australian National University. Department of Linguistics. Asia-Pacific Linguistics International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics (12th: 2012 : Bali, Indonesia) Cover illustration: courtesy of Vida Mastrika Typeset by I Wayan Arka and Vida Mastrika .