Cutaneous Balamuthia Mandrillaris Infection As a Precursor To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

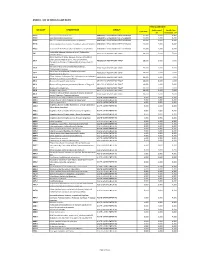

Annex 1: List of Medical Case Rates

ANNEX 1. LIST OF MEDICAL CASE RATES FIRST CASE RATE ICD CODE DESCRIPTION GROUP Professional Health Care Case Rate Fee Institution Fee P91.3 Neonatal cerebral irritability ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.4 Neonatal cerebral depression ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.6 Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy of newborn ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.8 Other specified disturbances of cerebral status of newborn ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.9 Disturbance of cerebral status of newborn, unspecified ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 Peritonsillar abscess; Abscess of tonsil; Peritonsillar J36 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 cellulitis; Quinsy Other diseases of larynx; Abscess of larynx; Cellulitis of larynx; Disease NOS of larynx; Necrosis of larynx; J38.7 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Pachyderma of larynx; Perichondritis of larynx; Ulcer of larynx Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscess; J39.0 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Peripharyngeal abscess Other abscess of pharynx; Cellulitis of pharynx; J39.1 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Nasopharyngeal abscess Other diseases of pharynx; Cyst of pharynx or nasopharynx; J39.2 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Oedema of pharynx or nasopharynx J85.1 Abscess of lung with pneumonia ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 J85.2 Abscess of lung without pneumonia; Abscess of lung NOS ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY -

Natural Remedies of Common Human Parasites and Pathogens

ACTA SCIENTIFIC MICROBIOLOGY (ISSN: 2581-3226) Volume 2 Issue 11 November 2019 Investigation Paper Natural Remedies of Common Human Parasites and Pathogens Omar M Amin* Parasitology Center, Scottsdale, Arizona *Corresponding Author: Omar M Amin, Parasitology Center, Scottsdale, Arizona. Received: July 12, 2019; Published: October 16, 2019 DOI: 10.31080/ASMI.2019.02.0401 • Bleeding. • Appetite changes. • Malabsorption. • Mucus. • Rectal itching. • Gut leakage. • Poor digestion. • Systemic/other symptoms • Fatigue. • Skin rash. • Dry cough. • Brain fog/memory loss. • Lymph blockage. Figure 1 • Allergies. • Nausea. Diagnosis and management of: • Muscle or joint pain. • Parasitic organisms and agents of medical and public • Dermatitis. health importance in fecal, blood, skin, urine specimens. • Headaches. • Toxicities related to Neurocutaneous Syndrome (NCS). • Insomnia. Development of anti-parasitic herbal products (F/C/R) Edu- How we get infected cational services: workshops, seminars, training and publications Drinking water or juice: Giardia, Cryptosporidium. provided. 1. 2. Skin contact with contaminated water: Schistosomi- Consultations and protocols for herbal and allopathic treat- asis, swimmers itch. ments. Research: over 220 publications on parasites from all con- Food (fecal-oral infections): most protozoans, ex., tinents. 3. Blastocysts, Entamoeba spp. and worms: Ascaris. Why test? 4. Arthropods: Lyme disease, plague, typhus, etc. You need to be tested if you have one or more of these symp- 5. Air: Upper respiratory tract infections (viruses, bac- toms: teria), ex GI symptoms 6. Pets: Hydatid., flu, Valleycyst disease,fever, Hanta heart virus. worm, larva mi- grans (dogs), Toxoplasma (cats), Taenia (beef, swine. • Diarrhea/constipation. People (contagious diseases): AIDS, herpes. • Irritable bowel 7. Soil: hook worms, thread worms. • Cramps 8. -

Die Prinzipien Der Chirurgischen Therapie Beim Fortgeschrittenen

Aus der Chirurgischen Klinik und Poliklinik - Innenstadt, der Ludwig-Maximilian- Universität-München Direktor: Prof. Dr. med. Wolf Mutschler Die Prinzipien der chirurgischen Therapie beim fortgeschrittenen Pyoderma gangränosum Dissertation zum Erwerb des Doktorgrades der Medizin an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München vorgelegt von Christoph Hendrik Volkering aus Groß-Gerau 2008 Mit Genehmigung der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität München Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Sigurd Keßler Mitberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Hans C. Korting Priv. Doz. Dr. Martin K. Angele Dekan: Prof. Dr. med. Dr. h.c. Maximilian Reiser, FACR Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 20.11.2008 - 2 - INHALT 1. Einleitung: ........................................................................................................... - 6 - 1.1. Das Pyoderma gangränosum: ..................................................................... - 6 - 1.1.1. Geschichte: ......................................................................................... - 6 - 1.1.2. Inzidenz: ............................................................................................. - 6 - 1.1.3. Assoziierte Erkrankungen: .................................................................. - 7 - 1.1.4. Typen des Pyoderma gangränosum: .................................................. - 9 - 1.1.5. Histopathologie: ................................................................................ - 12 - 1.1.6. Pathogenese: ................................................................................... -

Perineal Amoebiasis

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.55.3.234 on 1 March 1980. Downloaded from 234 Yoshioka and Miyata damage in our patient, as speculated by Vachon logical tests in our patient showed any abnormality, et al.,5 because liver function was normal or border- nor was there any evidence of other autoimmune line, and HBV antigenaemia persisted even after the disease. anaemia improved and the DAGT had become negative. The role of HBV in the pathogenesis of References AIHA has thus been unclear. Dacie J V. The autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. In: From many recent studies of type B hepatitis6 it is The haemolytic anaemias; congenital and acquired. Part 2. suggested that a defect of cell-mediated immunity London: Churchill, 1962: 539. may yield the carrier state ofHBV. This hypothesis is 2 Zuelzer W W, Mastrangelo R, Stulberg C S, Poulik M D, consistent with the fact that newborn babies may be Page R H, Thompson R I. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Natural history and viral-immunologic inter- infected from their HBV-carrier mother, resulting in actions in childhood. Am JMed 1970; 49: 80-93. the persistent carrier state.7 Likewise, the role of 3 Barrett-Connor E. Anemia and infection. Am J Med cellular immunity in the pathogenesis of AIHA has 1972; 52: 242-53. become clearer. Kruger et al.8 suggested that an 4 Habibi B, Homberg J-C, Schaison G, Salmon C. Auto- immune hemolytic anemia in children. A review of 80 imbalance between reduced T-cells and increased but cases. Am JMed 1974; 56: 61-9. -

5D4181239216c.Pdf

http://www.shamela.ws مت إعداد هذا امللف آليا بواسطة املكتبة الشاملة الكتاب: اﻷمراض اجللدية لﻷطفال املؤلف: الدكتور حممود حجازي ]موافق للمطبوع[ مﻻحظة: ]هذا الكتاب من كتب املستودع مبوقع املكتبة الشاملة[ اﻷمراض اجللدية لﻷطفال املؤلف / الدكتور ـ حممود حجازى ----------------- الفصل اﻷول مركبات اجللد الفهرس الفصل التايل فهرس الصور حبث اخلط املائل يف هذا الكتاب ميثل رأي وخربة املؤلف ****** مركبات اجللد جلد اجلنني: يف اﻷايم اﻷوىل من حياة اجلنني تتكون الطبقة السطحية للجلد من طبقة واحدة من اخلﻻاي حيث تتحول إىل طبقتني بني اﻷسبوع اخلامس والسادس، السطحية هي البشرة والسفلية هي الطبقة النامية من اجللد. إن الطبقة النامية هي املسؤولة عن تكوين معظم املكوانت الظهارية للجلد مثل الطبقة القاعدة والغدد العرقية. أما اخلﻻاي الظهارية النامية فإهنا مسؤولة عن تكوين الغدد الدهنية والغدد العرقية وغدد »أبو كراين« العرقية وجراب الشعر أما طبقة مالييجى فتتكون يف الشهر الرابع من عمر اجلنني. جلد الطفل: جلد الطفل له ملمس انعم ويشبه جلد البالغ من الناحية التشرحيية لﻷنسجة مع بعض الفروقات البسيطة. إن طبقة البشرة من اجللد يف اﻷطفال هي نفسها يف البالغني إﻻ أهنا أقل متاسكاً والفرق الرئيسي واهلام هو عدم النضوج الكامل لنسيج الكوﻻجني وجراب الشعر والغدد الدهنية يف اﻷطفال. كما أن البشرة السطحية مع طبقة اﻷدمة السفلية أقل متاسكاً يف اﻷطفال وهذا يفسر حدوث اﻷثر اﻷكثر تفاعﻻً نتيجة املؤثرات البسيطة يف اﻷطفال، حيث أن لدغة احلشرات قد حتدث فأليل جلدية. كما وأن التغريات نتيجة اﻻختﻻف يف نسبة مساحة اجللد إىل جسم اﻷطفال وكذلك نسبة نشاط اﻷوعية الدموية وكذلك القابلية للتعرق الزائد، كل ذلك له عﻻقة هامة على تنظيم حرارة جسم اﻷطفال، حيث أن بعض املؤثرات البسيطة قد تؤدي إىل املزيد من فقدان حرارة جسم اﻷطفال. -

Guidebook On

Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Guidebook on ICD 10 ICD-10 Coding January 2015 Third edition Management Information System (MIS) Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) Mohakhali, Dhaka-1212 www.dghs.gov.bd in collaboration with Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Guidebook on ICD 10 ICD-10 Coding January 2015 Third edition Management Information System (MIS) Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) Mohakhali, Dhaka-1212 www.dghs.gov.bd in collaboration with Special Acknowledgement: Professor Dr. Deen Mohammad Noorul Huq Director General of Health Services Dr. N. Paranietharan WHO Representative to Bangladesh Editorial Board For This Edition Editor: Professor Dr. Abul Kalam Azad ADG (Planning & development) & Director-MIS-Health, DGHS Contributors: Dr. Rashidun Nessa Deputy Director, Management Information System, DGHS Professor Dr. Md. Ayub Ali Chowdhury Professor of Nephrology, National Institute of Kidney Diseases & Urology, Dhaka Professor Dr. MAK Azad Chowdhury Professor, Dept. of Neonatology, Dhaka Shishu Hospital Professor Dr. Ismail Hossain Associate Professor, Dept. of Medicine Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College Hospital Dr. Md. Habibullah Talukder Raskin Associate Professor, Dept. of Cancer Epidemiology, NICR & H Dr. Mahmudul Haque Assistant Professor, Dept. of Community Medicine, NIPSOM Dr. Motlabur Rahman Assistant Professor, Dept. of Medicine, DMCH Dr. Ashish Kumar Saha Assistant Director, MIS, DGHS Dr. Lokman Hakim Program Manager (HIS & eHealth), MIS, DGHS Dr. Gowsal Azam Deputy Chief (Medical), MIS, DGHS Dr. Sultan Shamiul Bashar Medical Officer, MIS, DGHS Dr. Jeenat Maitry Medical Officer, MIS, DGHS Contributors of Second Edition Editor: Professor Dr. Abul Kalam Azad Additional Director General (Planning & Development) & Director, MIS-Health, DGHS Contributors: Dr. -

Review Article

DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/2146 REVIEW ARTICLE SKIN MANIFESTATIONS OF GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASES: A REVIEW Manisha Nijhawan1, Puneet Agarwal2, Sandeep Nijhawan3, Prashant4, Abhishek Saini5 HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Manisha Nijhawan, Puneet Agarwal, Sandeep Nijhawan, Prashant, Abhishek Saini. “Skin Manifestations of Gastrointestinal Diseases: A Review”. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 2014; Vol. 3, Issue 09, March 3; Page: 2357-2372, DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/2146 ABSTRACT: Skin is the largest organ of human body and stands as a guard for our internal organs. It can be regarded as a mirror giving a reflection of metabolic, biochemical and functional status of our internal organs. Dermatologists/Gastroenterologist should be aware of the dermatological manifestations as these change may be the first clue that a patient has underlying gastrointestinal (GI) or liver disease. Recognizing these signs is important in early and appropriate diagnosis. This article reviews the important dermatological manifestation of various GI and liver diseases. KEYWORDS: Skin and GI. Different dermatological manifestation in gastrointestinal diseases can be classified as:- 1) Specific skin manifestations 2) Reactive skin manifestations 3) Skin manifestations secondary to the deficiency of nutrients due to GI disease 4) Skin manifestations secondary to the treatment For clinician skin manifestation can be simply classified as- 1. Dermatological manifestations in benign GI diseases 2. Dermatological manifestations in malignant GI disease J of Evolution of Med and Dent Sci/ eISSN- 2278-4802, pISSN- 2278-4748/ Vol. 3/ Issue 09/ Mar 3, 2014 Page 2357 DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/2146 REVIEW ARTICLE A: Skin manifestations in esophageal diseases: Dysphagia: Esophageal webs This is a developmental abnormality with one or more horizontal membrane in upper esophagus. -

Cutaneous Amebiasis in Pediatrics

OBSERVATION Cutaneous Amebiasis in Pediatrics Mario L. Magan˜a, MD; Jorge Ferna´ndez-Dı´ez, MD; Mario Magan˜a,MD Background: Cutaneous amebiasis (CA), which is still Conclusions: Cutaneous amebiasis always presents with a health problem in developing countries, is important painful ulcers. The ulcers are laden with amebae, which to diagnose based on its clinical and histopathologic are relatively easy to see microscopically with routine features. stains. Erythrophagocytosis is an unequivocal sign of CA. Amebae reach the skin via 2 mechanisms: direct and in- Observations: Retrospective medical record review of direct. Amebae are able to reach the skin if there is a lac- 26 patients with CA (22 adults and 4 children) treated from eration (port of entry) and if conditions in the patient 1955 to 2005 was performed. In addition to the age and are favorable. Amebae are able to destroy tissues by means sex of the patients, the case presentation, associated ill- of their physical activity, phagocytosis, enzymes, secre- ness or factors, and method of establishing the diagnosis, tagogues, and other molecules. clinical pictures and microscopic slides were also analyzed. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(10):1369-1372 UTANEOUS AMEBIASIS (CA) ria, are opportunistic organisms that act as can be defined as damage pathogens, usually in the immunocompro- to the skin and underly- mised host, who can develop disease in any ing soft tissues by tropho- organ, such as the skin and central ner- zoites of Entamoeba histo- vous system. This kind of amebiasis has be- lytica, the only pathogenic form for humans. come more common during the last few C 8-18 Cutaneous amebiasis may be the only ex- years. -

List of ICD Codes (V.2009 and V.2012 ICD-10-CA¹)

List of ICD Codes (v.2009 and v.2012 ICD-10-CA¹) ICD Code Short Description Long Description A00 Cholera Cholera A00-A09 Intestinal infectious diseases Intestinal infectious diseases (A00-A09) A000 Cholera dt 01 biovar cholerae Cholera due to Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar cholerae A001 Cholera dt biovar eltor Cholera due to Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar eltor A009 Cholera unspecified Cholera, unspecified A01 Typhoid and paratyphoid fevers Typhoid and paratyphoid fevers A010 Typhoid fever Typhoid fever A011 Paratyphoid fever A Paratyphoid fever A A012 Paratyphoid fever B Paratyphoid fever B A013 Paratyphoid fever C Paratyphoid fever C A014 Paratyphoid fever unspecified Paratyphoid fever, unspecified A02 Other salmonella infections Other salmonella infections A020 Salmonella enteritis Salmonella enteritis A021 Salmonella sepsis Salmonella sepsis A022 Localized salmonella infections Localized salmonella infections A028 Other specified salmonella infections Other specified salmonella infections A029 Salmonella infection unspecified Salmonella infection, unspecified A03 Shigellosis Shigellosis A030 Shigellosis due to Shigella dysenteriae Shigellosis due to Shigella dysenteriae A031 Shigellosis due to Shigella flexneri Shigellosis due to Shigella flexneri A032 Shigellosis due to Shigella boydii Shigellosis due to Shigella boydii A033 Shigellosis due to Shigella sonnei Shigellosis due to Shigella sonnei A038 Other shigellosis Other shigellosis A039 Shigellosis unspecified Shigellosis, unspecified A04 Other bacterial intestinal infections Other bacterial -

A00–B99 Certain Infectious and Parasitic Diseases

1 . Kode Gol. Jenis Penyakit No Title Of Diseases Penyakit Penyakit akibat infeksi & I A00–B99 Certain infectious and parasitic diseases Parasit Neoplasms Keganasan / kanker/tumor II C00–D48 Diseases of the blood and blood-forming Penyakit darah /kelainan III D50–D89 organs and certain disorders involving the darah /keganasan sistem immune mechanism imun Penyakit endokrin & IV E00–E90 Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases metabolik & nutrisi Mental and behavioural disorders Gangguan prilaku & mental V F00–F99 Diseases of the nervous system Penyakit sistem saraf VI G00–G99 Diseases of the eye and anexa Penyakit mata & adnexa VII H00–H59 VIII H60–H95 Diseases of the ear and mastoid process Penyakit telinga & mastoid Penyakit sistem sirkulasi IX I00–I99 Diseases of the circulatory system darah Diseases of the respiratory system Penyakit sistem pernafasan X J00–J99 XI K00–K93 Diseases of the digestive system Penyakit sistem pencernaan Penyakit kulit & jaringan XII L00–L99 Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue subkutan Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and Penyakit sistem otot/rangka XIII M00–M99 connective tissue & jaringan penyambung Penyakit sistem kemih & XIV N00–N99 Diseases of the genitourinary system kelamin Kehamilan, Persalinan & O00–O99 Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium XV nifas Certain conditions originating in the perinatal Periode perinatal XVI P00–P96 period Congenital malformations, deformations and Malformasi kongenital, XVII Q00–Q99 chromosomal abnormalities deformitas & abnormal Symptoms, signs -

Cutaneous Amebiasis: 50 Years of Experience

Cutaneous Amebiasis: 50 Years of Experience Jorge Fernández-Díez, MD; Mario Magaña, MD; Mario L. Magaña, MD Although cutaneous amebiasis (CA) is a rare of skin and subcutaneous tissues. Therefore, CA disease, it is a public health concern worldwide, is a particularly virulent form of amebiasis. particularly in developing nations. It gains impor- Cutis. 2012;90:310-314. tance because of its severe clinical course, which can be confused with other disorders. Therefore, knowledge of its clinical features, histopathology, utaneous amebiasis (CA) can be charac- and pathogenesis is essential. We present a retro- terized as injury to the skin and underly- spective analysis over 50 years of 26 patients with ing soft tissues by trophozoites of Entamoeba C 1,2 CA who were diagnosed and treated at 2 Mexican histolytica. Other species of the genus such as institutions. Our main focus was to draw clinical Entamoeba hartmanni, Entamoeba coli, Entamoeba information to identify mechanisms by which ame- gingivalis,3 and Entamoeba dispar4 are considered bae reach the skin, occurring in a relatively small nonpathogenic. Entamoeba dispar has now been rec- percentage of infected individuals. The recorded ognized as responsible for many cases of amebiasis data included age and sex ofCUTIS the patients, form of in patients who were previously considered “healthy presentation, any associated illnesses and/or fac- carriers.” It is morphologically indistinguishable from tors, and methods for diagnosis. Histologic slides E histolytica but genetically and serologically dif- were reviewed in all cases; cytologic preparations ferent.5,6 Entamoeba moshkovskii is morphologically also were available for 6 cases. Most patients indistinguishable from E histolytica and E dispar but were male (overall male to female ratio, 1.9 to 1). -

Colour Atlas of Tropical Dermatology and Venerology

K.F. Schaller (Editor) Colour Atlas of Tropical Dermatology and Venerology In collaboration with F. A. Bahmer • D. W. Biittner • H. Lieske • H. Rieth S. W. Wassilew • F. Weyer With 601 Figures in Colour Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York London Paris Tokyo Hong Kong Barcelona Budapest Table of Contents Chapter 1 Viral Diseases of the Skin 1 Ecthyma 49 Erysipelas 50 Variola Vera 1 Scarlatina 51 Molluscum Contagiosum 3 Varicella 4 Nonpyococcal Infections 52 Herpes Zoster 5 Pseudofolliculitis 52 Herpes Simplex 6 Folliculitis Cheloidalis 53 Verrucae Planae 7 Tropical Ulcer 54 Verrucae Vulgares 8 Anthrax 55 Verrucae Plantares 9 Bartonellosis 56 Condylomata Acuminata 10 Rhinoscleroma 57 Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis 11 Erysipeloid 58 Measles 12 Cancrum Oris 58 Rubella 13 Erythrasma 59 Dengue Fever 13 Plague 60 Sandfly Fever 14 Rat Bite Fever 62 Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection 15 Chapter 4 Endemic Treponematoses 63 Chapter 2 Rickettsial Diseases 16 Yaws 64 Epidemic Typhus 16 Pinta 68 Endemic Typhus 17 Endemic Syphilis 69 Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever 18 Tick Bite Fever 19 Chapter 5 Sexually Transmitted Diseases 70 Rickettsial Pox 20 Scrub Typhus 21 Syphilis 70 Gonorrhoea 74 Chancroid 75 Chapter 3 Bacterial Dermatoses 22 Lymphogranuloma Venereum 76 Granuloma Inguinale 77 Mycobacterial Infections 22 Leprosy 22 Tuberculosis 37 Chapter 6 Superficial Fungal Dermatoses 79 Mycobacterium ulcerans Infection 39 Tinea Imbricata 79 Mycobacterium marinum Infection ' 40 Tinea Nigra 80 Pyococcal Infections 41 Piedra 81 Follicular Impetigo 41