Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: an Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

2010-11 Naidheachd.Pub

An Naidheachd Againne The Newsletter of An Comunn Gàidhealach Ameireaganach / The American Gaelic Society Samhradh-Foghar 2010, Leabhar XXVI, Aireamh 4 Summer-Fall 2010, Volume XXVI, No. 4 Anything But Maudlin: The Gaelic College Mod by Heather Sparling One of the more controversial Gaelic cultural events in Cape Breton’s history has been the annual Mod held at the St. Ann’s Gaelic College of Celtic Arts & Crafts. The first annual Mod was held in the same year as the College’s founding: in 1939. The Gaelic word “mod” originally referred to a court held by a Highland chief for settling disputes over rent and other matters. Today, it refers to a Gaelic cultural competition that may include recitation, storytelling, drama, instrumental performance (especially bag- pipes), dance and Gaelic song. Competitive Gaelic mods were first developed in Scotland, where the Royal National Mod was established in 1892 based on the Welsh equivalent, the Eisteddfod, which was established in 1880. in the mid-1950s. This was no minor feat since road Cape Breton’s Mod was a major success in its access to the College was limited at the time and early days, attracting 4,000-5,000 attendees within many people arrived from places such as North less than ten years, peaking at 7,000-8,000 attendees Sydney and its environs via boat. It was so popular that county mods began to be held throughout the Place your message here. For maximum impact, use two or threpe sentences. rovince, including in Port Hood, Iona, Sydney, New In This Issue Glasgow, Amherst and Dartmouth. -

Pdf Shop 'Celtic Gold' in Peel

No. 129 Spring 2004/5 €3.00 Stg£2.50 • SNP Election Campaign • ‘Property Fever’ on Breizh • The Declarationof the Bro Gymraeg • Istor ar C ’herneveg • Irish Language News • Strategy for Cornish • Police Bug Scandal in Mann • EU Constitution - Vote No! ALBA: COM.ANN CEILTFACH * BREIZH: KFVTCF KELT1EK * CYMRU: UNDEB CELTA DD * EIRE: CON RAD H GEILTE AC H * KERNOW: KtBUNYANS KELTEK * MANNIN: COMlVbtYS CELTIAGH tre na Gàidhlig gus an robh e no I a’ dol don sgoil.. An sin bhiodh a’ huile teasgag tre na Gàidhlig air son gach pàiste ann an Alba- Mur eil sinn fhaighinn sin bidh am Alba Bile Gàidhlig gun fheum. Thuig Iain Trevisa gun robh e feumail sin a dhèanamh. Seo mar a sgrìohh e sa bhli adhna 1365, “...dh’atharraich Iain à Còm, maighstir gramair, ionnsachadh is tuigsinn gramair sna sgoiltean o’n Fhraingis gu TEACASG TRE NA GÀIDHLIG Beurla agus dh’ionnsaich Richard Pencrych an aon scòrsa theagaisg agus Abajr gun robh sinn toilichte cluinntinn Inbhirnis/Inverness B IVI 1DR... fon feadhainn eile à Pencrych; leis a sin, sa gun bidh faclan Gaidhlig ar na ceadan- 01463-225 469 e-mail [email protected] bhliadhna don Thjgheama Againn” 1385, siubhail no passports again nuair a thig ... tha cobhair is fiosrachadh ri fhaighinn a an naodhamh bliadhna do’n Righ Richard ceann na bliadhna seo no a dh’ aithgheor thaobh cluich sa Gàidhlig ro aois dol do an dèidh a’Cheannsachaidh anns a h-uile 2000. Direach mar a tha sinn a’ dol thairis sgoil, Bithidh an t-ughdar is ionadail no sgoil gràmair feadh Sasunn, tha na leana- air Caulas na Frainge le bata no le trean -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

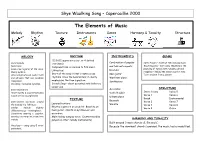

The Elements of Music

Skye Waulking Song – Capercaillie 2000 The Elements of Music Melody Rhythm Texture Instruments Genre Harmony & Tonality Structure MELODY RHYTHM INSTRUMENTS GENRE 12/8 (12 quavers in a bar, or 4 dotted Combination of popular Vocal melody: crotchets) Celtic Fusion – Scottish folk and pop music. Waulking song – work song. Waulking is the Pentatonic. Compound time is common to folk music. and folk instruments. Uses a low register of the voice. pounding of tweed cloth. Usually call and Lilting feel. Drum kit Mainly syllabic. response – helped the women work in time. Start of the song: hi-hat creates cross Alternates between Gaelic (call) Bass guitar Text is taken from a lament. and phrases that use vocables rhythms. Once the band enters it clearly Wurlitzer piano (response) emphasises the time signature. Synthesizer Vocables = nonsense syllables. Scotch Snap – short accented note before a longer one. STRUCTURE Instrumentalists: Accordion Short motifs & Countermelodies Violin (fiddle) Intro: 8 bars. Verse 5 Verse 1 Verse 6 based on the vocal phrases. Uileann pipes Break Instrumental TEXTURE Bouzouki Instruments improvise around Verse 2 Verse 7 Layered texture: the melody in a folk style. Whistle Verse 3 Verse 8 Rhythmic pattern on drum kit. Bass line on Similar melody slightly Verse 4 Outro bass guitar. Chords on synthesizer and different ways = heterophonic. Sometimes weaving a complex, accordion. weaving counterpoint around the Main melody sung by voice. Countermelodies HARMONY AND TONALITY melody. played on other melody instruments) Built around 3 main chords: G, Em and C. Vocal part = sung using E minor Because the dominant chord is avoided, the music has a modal feel. -

Scottish Studies 36

SCOTTISH STUDIES 36 Scottish Studies The Journal of the School of Scottish Studies University of Edinburgh Vol. 36 2011-2013 EDITED BY JOHN SHAW Published by The School of Scottish Studies University of Edinburgh 2013 Articles are invited and should be sent to: Dr John Shaw The Editor, Scottish Studies The School of Scottish Studies The University of Edinburgh 27 George Square Edinburgh EH8 9LD All articles submitted are sent out to readers for peer review. Enquiries may be made by email to: [email protected] The journal is published annually and costs £12. Subscriptions should be sent to The Subscription Secretary, Scottish Studies, at the address above. This volume of Scottish Studies is also available online: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/scottishstudies The School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh Printed in Great Britain by Airdrie Press Services ISBN 978-0-900949-03-6 Contents Contributors vii Editorial ix Per G.L. Ahlander 1 Richard Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer – A Flying Hebridean in Disguise? V.S. Blankenhorn 15 The Rev. William Matheson and the Performance of Scottish Gaelic ‘Strophic’ Verse. Joshua Dickson 45 Piping Sung: Women, Canntaireachd and the Role of the Tradition-Bearer William Lamb 66 Reeling in the Strathspey: The Origins of Scotland’s National Music Emily Lyle 103 The Good Man’s Croft Carol Zall 125 Learning and Remembering Gaelic Stories: Brian Stewart ‘ Book Reviews 140 Contributors Per G.L. Ahlander, School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh V. S. Blankenhorn, School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh Joshua Dickson, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland William Lamb, School of Scottish Studies Emily Lyle, University of Edinburgh Carol Zall, Cambridge, MA, USA vii Editorial Applications of digital technology have figured large in recent research and publications in Scottish ethnology. -

Spamm Magazine in New PHILADBLPHIA, LANCASTER,

;;, '" FEATUREARTlCliES w~iJ -~ TO~~4j)IAOR BALI coNFalWNCE ;Q){)RNOrCO . .. .IJ,uf much more ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Page 2 SUBSCRIBE TODA V PURPOSE We are confident that ACM Journal will serve as ACM Journal is meant to provide an overview of an important tool for you. Whether programming activity in Alternative Christian Music , connect for an alternative show, writing plays, recording, individuals working in different areas of Ministry, performing, or just trying to keep up-to-date - and convey practical and objective information on we can be an important resource. a variety of issues and topics. We are, of course, very interested in meeting To accomplish this, different ministry areas are vour needs. We have answered every letter highlighted in each issue. The developing area of ~king for any type of information so far , and college progressive and dance-oriented music are have put several people with common interests in regular sections, including domestic, international touch with each other. If you would like to see and independent artists. Christian art, t heatre, certain topics covered , favorite artist s dance and many other ministries deserve special interviewed, or anything else for that matter, attention and will be featured often. Our hope is please drop us a line! We hope to provide all the that you find this publication a useful resource information you require, improve continuously, for your ministry in your community . We look and always remain accessible to our readers forward to your participation through suggestions, PO Box 1273 I. individually. ideas and information. Please share this with We can't do this alone. -

EVENTS SECTION ONE 151.Indd

.V1$ .VR5 :GV``V1R.Q:R5 Q`JQ1:75CVQ`V115 VC7 %QG1CV7 VC7 %QG7 I:1C71J`Q Q`JQ1:7R@1]8HQ8%@ 1118IHC:%$.C1J]C:J 8HQ8%@ 1118 Q`JQ1:7@1]8HQ8%@ 22 Francis Street Stornoway •#%& ' Insurance Services R & G RMk Isle of Lewis Jewellery HS1 2NB •#'&( ) Risk Management XPSFTCPQ t: 01851 704949 #* +# ,( ADVICE • Health & Safety YOU CAN ( )) www.rmkgroup.co.uk TRUST ISTANBUL KEBABS FISH ‘n’ CHIPS BURGERS CURRIES PIZZAS RESTAURANT & TAKEAWAY * +(,-../0/1 & ' )'&23 )# !%5FAMILY FRIENDLY RESTAURANT WITH OVER )!%530 YEARS SERVING THE ISLAND H SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE OPEN 7 DAYS Tues-Thursday 12pm-2.30pm 4.30-10.30pm Friday-Saturday: 12pm-3pm 4pm till late The local one Sunday: 12pm till late (open all day Sunday) stop solution for all 24 South Beach Street, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis your printing and Tel: 01851 700299 design needs. 1st 01851 700924 [email protected] www.sign-print.co.uk @signprintsty Church House, James St. Stornoway birthday BANGLA SPICE party for !7ryyShq lottery &"%#% !"#$% ! &#$% '() ! () *+#$% , $#$% -.() ! -.() / See page 2 Disney Day at Artizan !"# 2 " "' "' ' +4 &'("' )* $' '+ $" # # # # # # # \ ,-.0$1 " $"$ % uvpp G vs5uvpp '$ & '%$ Ury) '$ &!""$ \ S Ury) '$ &$( (Ah) '$ &#&#" ! !"#$"%& %'$ ! EVENTS SECTION ONE - Page 2 www.hebevents.com 06/09/18 - 03/10/18 1st birthday party for Western Isles Lottery he Western Isles Lottery's Disney Themed Day on Saturday E> > NH Ņ TSeptember 1st was a great success as families fl ocked into Stornoway to take part in various events.. % The Lottery Team say they are hugely grateful to every business and organisation that worked so hard for this event to be such a success, particularly as it was postponed for a week and had to be re-organised. -

Indigenous Language Revitalisation in Aotearoa New Zealand & Alba

Indigenous language revitalisation in Aotearoa New Zealand & Alba Scotland Catriona Elizabeth Timms (Kate Timms-Dean) A thesis submitted to the University of Otago in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. i 28 February 2013 1 Table of Contents List of Tables _________________________________________________________________ 5 List of Figures ________________________________________________________________ 5 List of Abbreviations ___________________________________________________________ 6 Glossary of Māori terms ________________________________________________________ 9 Glossary of Gàidhlig terms _____________________________________________________ 18 Mihimihi ___________________________________________________________________ 20 Acknowledgements ___________________________________________________________ 22 Abstract ____________________________________________________________________ 24 Introduction: Why revive endangered languages? __________________________________ 25 Defining Indigenous language revitalisation __________________________________ 27 Case Study 1: Te reo Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand __________________________ 32 Case Study 2: Gàidhlig in Alba Scotland ______________________________________ 38 Conclusion __________________________________________________________________ 45 1. Language Policy and Planning _________________________________________________ 52 What is language planning and language policy? ______________________________ 53 Why use language policy and planning in -

Miscellany Presented to Kuno Meyer by Some of His Friends and Pupils On

g: fyxmll mmretjsitg ^ilravg leltic Collection THE GIFT OF 3ame$ Morgan fiart """""'*" "'"""^ PB 14.M6lia6 3 1924 026 503 148 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026503148 MISCELLANY PRESENTED TO KUNO MEYER BY SOME OF HIS FRIENDS AND PUPILS ON THE OCCASION OF HIS APPOINTMENT TO THE CHAIR OF CELTIC PHIL0LOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF BERLIN EDITED BY OSBOEN BERGIN and CARL MARSTRANDER HALLE A.S. MAX NIEMEYEB 1912 MISCELLANY PRESENTED TO KUNO MEYER BY SOME OF HIS FKIENDS AND PUPILS ON THE OCCASION OF HIS APPOINTMENT TO THE CHAIR OF CELTIC PHILOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF BERLIN EDITED BY OSBOKN BERGIN and CARL MARSTRANDER HALLE A. S. MAX NIEMEYEB 1912 Contents. Page Alfred A ns combe, Lucius Eex and Eleutherius Papa .... 1 George Henderson, Arthurian motifs in Gadhelic literature . 18 Christian Sarauw, Specimens of Gaelic as spoken in the Isle of Skye 34 Walter J. Purton, The dove of Mothar-I-Eoy 49 J. H. Lloyd, Prom the Book of Clanaboy 53 R. ThurneysenI, Das Futurum von altirisch agid 'er treibt' .... 61 E. Priehsch, „Grethke, war umb heffstu mi" etc., das „Bauer-Lied" Simon Dachs 65 E. An wyl, The verbal forms in the White Book text of the four branches of the Mabinogi 79 H. Gaidoz, Le mal d'amour d'Ailill Anguba et le nom de Laennec . 91 G. Dottin, Sur I'emploi de .i 102 E. Ernault, Les nouveaux signes orthographiques dans le breton du Mirouer Ill J.