Hebridean Folksongs Vol I 15 August

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

2010-11 Naidheachd.Pub

An Naidheachd Againne The Newsletter of An Comunn Gàidhealach Ameireaganach / The American Gaelic Society Samhradh-Foghar 2010, Leabhar XXVI, Aireamh 4 Summer-Fall 2010, Volume XXVI, No. 4 Anything But Maudlin: The Gaelic College Mod by Heather Sparling One of the more controversial Gaelic cultural events in Cape Breton’s history has been the annual Mod held at the St. Ann’s Gaelic College of Celtic Arts & Crafts. The first annual Mod was held in the same year as the College’s founding: in 1939. The Gaelic word “mod” originally referred to a court held by a Highland chief for settling disputes over rent and other matters. Today, it refers to a Gaelic cultural competition that may include recitation, storytelling, drama, instrumental performance (especially bag- pipes), dance and Gaelic song. Competitive Gaelic mods were first developed in Scotland, where the Royal National Mod was established in 1892 based on the Welsh equivalent, the Eisteddfod, which was established in 1880. in the mid-1950s. This was no minor feat since road Cape Breton’s Mod was a major success in its access to the College was limited at the time and early days, attracting 4,000-5,000 attendees within many people arrived from places such as North less than ten years, peaking at 7,000-8,000 attendees Sydney and its environs via boat. It was so popular that county mods began to be held throughout the Place your message here. For maximum impact, use two or threpe sentences. rovince, including in Port Hood, Iona, Sydney, New In This Issue Glasgow, Amherst and Dartmouth. -

Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: an Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions

Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: An Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions by Anna Wright BMus, Edinburgh Napier University, 2015 MMus, University of British Columbia, 2018 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Ethnomusicology) The University of British Columbia (Vancouver) April 2020 © Anna Wright, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: An Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions submitted by Anna Wright in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Ethnomusicology Examining Committee: Nathan Hesselink Supervisor, Chair, Ethnomusicology Department, School of Music, UBC Michael Tenzer Supervisory Committee Member, Professor, Ethnomusicology Department, School of Music, UBC ii Abstract This thesis examines the use of seist chorus sections in the Scottish Gaelic song tradition. These sections consist of nonsense syllables, or vocables. Although lacking semantic meaning, such vocables often provoke the joining in of the audience or listening group. The use of these vocable sections can be seen to have evolved in both their physical (sonic) characteristics and their social use and function over time while still maintaining a marked presence in Scottish Gaelic music across many genres and generations. I briefly examine theories surrounding seist vocables’ inception, interview three practitioners of Gaelic song about seist choruses’ inception and evolving function, examine four songs dating from a period spanning 1601-2016, and relate my findings to Scotland’s constantly evolving social and political climate. -

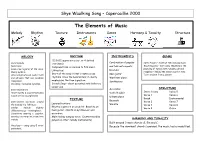

The Elements of Music

Skye Waulking Song – Capercaillie 2000 The Elements of Music Melody Rhythm Texture Instruments Genre Harmony & Tonality Structure MELODY RHYTHM INSTRUMENTS GENRE 12/8 (12 quavers in a bar, or 4 dotted Combination of popular Vocal melody: crotchets) Celtic Fusion – Scottish folk and pop music. Waulking song – work song. Waulking is the Pentatonic. Compound time is common to folk music. and folk instruments. Uses a low register of the voice. pounding of tweed cloth. Usually call and Lilting feel. Drum kit Mainly syllabic. response – helped the women work in time. Start of the song: hi-hat creates cross Alternates between Gaelic (call) Bass guitar Text is taken from a lament. and phrases that use vocables rhythms. Once the band enters it clearly Wurlitzer piano (response) emphasises the time signature. Synthesizer Vocables = nonsense syllables. Scotch Snap – short accented note before a longer one. STRUCTURE Instrumentalists: Accordion Short motifs & Countermelodies Violin (fiddle) Intro: 8 bars. Verse 5 Verse 1 Verse 6 based on the vocal phrases. Uileann pipes Break Instrumental TEXTURE Bouzouki Instruments improvise around Verse 2 Verse 7 Layered texture: the melody in a folk style. Whistle Verse 3 Verse 8 Rhythmic pattern on drum kit. Bass line on Similar melody slightly Verse 4 Outro bass guitar. Chords on synthesizer and different ways = heterophonic. Sometimes weaving a complex, accordion. weaving counterpoint around the Main melody sung by voice. Countermelodies HARMONY AND TONALITY melody. played on other melody instruments) Built around 3 main chords: G, Em and C. Vocal part = sung using E minor Because the dominant chord is avoided, the music has a modal feel. -

Scottish Studies 36

SCOTTISH STUDIES 36 Scottish Studies The Journal of the School of Scottish Studies University of Edinburgh Vol. 36 2011-2013 EDITED BY JOHN SHAW Published by The School of Scottish Studies University of Edinburgh 2013 Articles are invited and should be sent to: Dr John Shaw The Editor, Scottish Studies The School of Scottish Studies The University of Edinburgh 27 George Square Edinburgh EH8 9LD All articles submitted are sent out to readers for peer review. Enquiries may be made by email to: [email protected] The journal is published annually and costs £12. Subscriptions should be sent to The Subscription Secretary, Scottish Studies, at the address above. This volume of Scottish Studies is also available online: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/scottishstudies The School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh Printed in Great Britain by Airdrie Press Services ISBN 978-0-900949-03-6 Contents Contributors vii Editorial ix Per G.L. Ahlander 1 Richard Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer – A Flying Hebridean in Disguise? V.S. Blankenhorn 15 The Rev. William Matheson and the Performance of Scottish Gaelic ‘Strophic’ Verse. Joshua Dickson 45 Piping Sung: Women, Canntaireachd and the Role of the Tradition-Bearer William Lamb 66 Reeling in the Strathspey: The Origins of Scotland’s National Music Emily Lyle 103 The Good Man’s Croft Carol Zall 125 Learning and Remembering Gaelic Stories: Brian Stewart ‘ Book Reviews 140 Contributors Per G.L. Ahlander, School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh V. S. Blankenhorn, School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh Joshua Dickson, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland William Lamb, School of Scottish Studies Emily Lyle, University of Edinburgh Carol Zall, Cambridge, MA, USA vii Editorial Applications of digital technology have figured large in recent research and publications in Scottish ethnology. -

Download PDF Booklet

Produced by John Shaw, Rosemary Hutchison and Tony Engle. Recorded by John Shaw and Rosemary Hutchison, August-September 1976. THE MUSIC OF CAPE BRETON Remastered by Tony Engle. Photograph (of Malcolm Angus MacLeod, Skir Dhu, Victoria County) by Ron Caplan. VOLUME 1 Notes and booklet by John Shaw. Sleeve design by Tony Russell. GAELIC TRADITION IN CAPE BRETON First published by TOPIC 1978. 1. An t-Each Ruadh Alexander Kerr with the North Shore Singers 2. Slow Air: Coilsfield House Dan Joe MacInnis violin with Theresa MacLeanpiano 3. Hinn, Heinn Thog Iad Amach Mrs Rod McLean 4. March, Reel & Jig: The Glencoe March/The Sandpoint/Untitled Joe Burke harmonica with Marie MacLellan piano 5. Mo Nigh An Donn As Bòidche Malcolm Angus MacLeod 6. Strathspeys & Reels: Captain Campbell/Marnoch Strathspey/Mrs General Campbell/ Allt a’ Ghobhainn (The Smith’s Burn)/ O, She’s Comical/Sandy MacIntyre’s Trip to Boston/Sir Reginald MacDonald/Dan J Campbell’s Reel Mike MacDougall violin with Mary Jessie MacDonald piano 7. Ma Phòsas Mi Lauchie MacLellan 8. Màili Dhonn, Bhòidheach Dhonn John Shaw with the North Shore Singers 9. Tha Mo Ghaol Air Àird a’ Chuain Tommy MacDonald 10. Strathspeys & Reels: Sir Thomas Sinclair Ray/The Highlanders’ Farewell/Miss Lyle’s Strathspey/Miss Lyle’s reel/ Sandy is my Darling/Bonnie Annie Alex Francis MacKay violin with Fr. John Angus Rankin piano 11. O A Hù A, Nighean Dubh, Nighean Donn Neil MacLean with the North Shore Singers 12. Jig & Hornpipe: Paddy’s Resource/The Flowers of Edinburgh Alex MacNeil mandolin with Charlie Dobbin mandolin and and Kevin McCormick piano 13. -

Inverness Gaelic Society

Inverness Gaelic Society Collection Last Updated Jan 2020 Title Author Call Number Burt's letters from the north of Scotland : with facsimiles of the original engravings (Burt, Edward), d. 1755 941.2 An English Irish dictionary, intended for the use of schools : containing upwards of eight thousand(Connellan, English Thaddeus),words, with d. their 1854 corresponding explanation491.623 in Irish The martial achievements of the Scots nation : being an account of the lives, characters and memorableAbercromby, actions, Patrick of such Scotsmen as have signaliz'd941.1 themselves by the sword at home and abroad and a survey of the military transactions wherein Scotland or Scotsmen have been remarkably concern'd from thefirst establishment of the Scots monarchy to this present time Officers and graduates of University & King's College, Aberdeen MVD-MDCCCLX Aberdeen. University and King's College 378.41235 The Welsh language 1961-1981 : an interpretative atlas Aitchison, J. W. 491.66 Scottish fiddlers and their music Alburger, Mary Anne 787.109411 Place-names of Aberdeenshire Alexander, William M. 929.4 Burn on the hill : the story of the first 'Compleat Munroist' Allan, Elizabeth B.BUR The Bridal Caölchairn; and other poems Allan, John Carter, afetrwards Allan (John Hay) calling808.81 himself John Sobiestki Stolberg Stuart Earail dhurachdach do pheacaich neo-iompaichte Alleine, Joseph 234.5 Earail Dhurachdach do pheacaich neo-iompaichte Alleine, Joseph 234.5 Leabhar-pocaid an naoimh : no guth Dhe anns na Geallaibh Alleine, Joseph 248.4 My little town of Cromarty : the history of a northern Scottish town Alston, David, 1952- 941.156 An Chomhdhail Cheilteach Inbhir Nis 1993 : The Celtic Congress Inverness 1993 An Chomhdhail Cheilteach (1993 : Scotland) 891.63 Orain-aon-neach : Leabhar XXI. -

The School of Scottish Studies and Language Policy and Planning for Gaelic ROBERT DUNBAR

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scottish Studies The School of Scottish Studies and Language Policy and Planning for Gaelic ROBERT DUNBAR ABSTRACT The School of Scottish Studies (the ‘School’) was inaugurated on 31 January 1951 as a semiautonomous institution within the University of Edinburgh, with the broad aim of studying ‘Scottish traditional life in its European setting, on lines similar to those developed in several Scandinavian institutes and, more recently, in Ireland and Wales’. Volume 37, pp 72-82 | ISSN 2052-3629 | http://journals.ed.ac.uk/ScottishStudies DOI: 10.2218/ss.v37i0.1794 http://dx.doi.org/10.2218/ss.37i0.1794 The School of Scottish Studies and Language Policy and Planning for Gaelic ROBERT DUNBAR The School of Scottish Studies (the ‘School’) was inaugurated on 31 January 1951 as a semi- autonomous institution within the University of Edinburgh, with the broad aim of studying ‘Scottish traditional life in its European setting, on lines similar to those developed in several Scandinavian institutes and, more recently, in Ireland and Wales’ (Kerr, n.d.: 1). The principal activities of the School have been described as the recording, documentation and study of oral traditions (e.g. tales, legends, proverbs, custom and belief), traditional song and instrumental music, material culture, and place-names, covering the whole of Scotland and including Gaelic and Scots-speaking districts (ibid). The School’s holdings comprise a sound archive of over 30,000 items, including -

John Lorne Campbell Was Born on 1 October, 1906, in Argyllshire, the Eldest Son of Col

JOHN LORNE CAMPBELL KSG, OBE, MA, DLitt(Oxon,Glas), LLD(St FrancisXavierUniversity,NovaScotia) John Lorne Campbell was born on 1 October, 1906, in Argyllshire, the eldest son of Col. Duncan Campbell of Inverneill, and died in Fiesole, Italy, on 25 April 1996. He was educated at Cargilfield School (1916-20), and Rugby (1920-25), where he won respect as a Classical scholar. After spending the year 1925-6 in Europe he went up to St John’s College, Oxford, where he studied Natural Science and Agriculture (1926-29), taking his BA in 1929 (MA 1933). During 1929-30 he took a diploma course in Rural Economy, and also gained practical experience as a farming pupil of Richard Tanner at Kingston Bagpuize. In 1932 he successfully submitted a postgraduate thesis whose subject, the history of the Scottish agricultural township, revealed another string to his bow: in addition to pursuing practical, contemporary studies in the natural sciences, John had nurtured a deep interest in history, including especially Scotland’s past. These humane enquiries would run parallel to, and frequently intersect with the scientific and practical agricultural concerns that equally continued to occupy him throughout his life. While he was still at Oxford he had been studying Scottish Gaelic language and literature. He was an active member of the Gaelic Club within the University, serving as its Secretary from 1927 to 1930; and he attended the classes of John Fraser, the Jesus Professor of Celtic, on an informal basis from 1928 until he left Oxford in 1932. In April of that year he made his first visit to Nova Scotia, where another of the principal strands in his scholarly life came to the surface. -

The Historical Plays of Donald Sinclair Aonghas Macleòid Independent Scholar the Gaelic Poet, Playwright and Essayist Donald Si

The Historical Plays of Donald Sinclair Aonghas MacLeòid Independent Scholar The Gaelic poet, playwright and essayist Donald Sinclair (Dòmhnall Mac na Ceàrdaich, 1885-1932) has received renewed attention in recent years, signalled most notably by the publication of a large selection of his writings (Mac na Ceàrdaich 2014) and a new academic interest in his work. (Mac Leòid 2012; Watson 2011: 29-30) The reassessment of Sinclair’s output stems in part from the role he plays as an innovator in Gaelic writing across a range of genres, developing Gaelic verse, prose and drama. This paper focuses on the latter, but argues that the development visible in his dramatic work reflects the experimental trajectory of his work in other media. Sinclair published six plays in total: two comedies Dòmhnull nan Trioblaid and Suiridhe Raoghail Mhaoil, both 1912; two historical dramas which are the focus of this essay, Fearann a Shinnsir (1913) and Crois-Tàra! (1914); and two plays for children Ruaireachan (1924) and Long nan Òg (1927). Of the two plays to be examined in this paper Fearann a Shinnsir (The Land of his Forebears) (1913) focuses on the Highland Clearances, utilising the history of Sinclair’s native island of Barra, to decry the outrages of the landlords whilst contributing to debates on land ownership prior to the First World War. The second historical play Crois-Tàra! (The Fiery Cross) (1914) is based on the 1745-46 Jacobite Rising under Charles Edward Stuart and examines the personal and political motivations of the Clanranald gentry and tenants. A noted character within the play is one of the pre-eminent Gaelic poets of the eighteenth century Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair [Alexander MacDonald] and Sinclair clearly questions the propagandist role of the poet within eighteenth-century Gaelic society. -

Tradition Label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Tradition Label Discography

Tradition label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Tradition Label Discography The Tradition Label was established in New York City in 1956 by Pat Clancy (of the Clancy Brothers) and Diane Hamilton. The label recorded folk and blues music. The label was independent and active from 1956 until about 1961. Kenny Goldstein was the producer for the label during the early years. During 1960 and 1961, Charlie Rothschild took over the business side of the company. Clancy sold the company to Bernard Solomon at Everest Records in 1966. Everest started issuing albums on the label in 1967 and continued until 1974 using recordings from the original Tradition label and Vee Jay/Horizon. Samplers TSP 1 - TraditionFolk Sampler - Various Artists [1957] Birds Courtship - Ed McCurdy/O’Donnell Aboo - Tommy Makem and Clancy Brothers/John Henry - Etta Baker/Hearse Song - Colyn Davies/Rodenos - El Nino De Ronda/Johnny’s Gone to Hilo - Paul Clayton/Dark as a Dungeon - Glenn Yarbrough and Fred Hellerman//Johnny lad - Ewan MacColl/Ha-Na-Ava Ba-Ba-Not - Hillel and Aviva/I Was Born about 10,000 Years Ago - Oscar Brand and Fred Hellerman/Keel Row - Ilsa Cameron/Fairy Boy - Uilleann Pipes, Seamus Ennis/Gambling Suitor - Jean Ritchie and Paul Clayton/Spiritual Trilogy: Oh Freedom, Come and Go with Me, I’m On My Way - Odetta TSP 2 - The Folk Song Tradition - Various Artists [1960] South Australia - A.L. Lloyd And Ewan Maccoll/Lulle Lullay - John Jacob Niles/Whiskey You're The Devil - Liam Clancy And The Clancy Brothers/I Loved A Lass - Ewan MacColl/Carraig Donn - Mary O'Hara/Rosie - Prisoners Of Mississippi State Pen//Sail Away Ladies - Odetta/Ain't No More Cane On This Brazis - Alan Lomax, Collector/Railroad Bill - Mrs.