Download PDF 8.01 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2003

Nations and Regions: The Dynamics of Devolution Quarterly Monitoring Programme Scotland Quarterly Report November 2003 The monitoring programme is jointly funded by the ESRC and the Leverhulme Trust Introduction: James Mitchell 1. The Executive: Barry Winetrobe 2. The Parliament: Mark Shephard 3. The Media: Philip Schlesinger 4. Public Attitudes: John Curtice 5. UK intergovernmental relations: Alex Wright 6. Relations with Europe: Alex Wright 7. Relations with Local Government: Neil McGarvey 8. Finance: David Bell 9. Devolution disputes & litigation: Barry Winetrobe 10. Political Parties: James Mitchell 11. Public Policies: Barry Winetrobe ISBN: 1 903903 09 2 Introduction James Mitchell The policy agenda for the last quarter in Scotland was distinct from that south of the border while there was some overlap. Matters such as identity cards and foundation hospitals are figuring prominently north of the border though long-running issues concerned with health and law and order were important. In health, differences exist at policy level but also in terms of rhetoric – with the Health Minister refusing to refer to patients as ‘customers’. This suggests divergence without major disputes in devolutionary politics. An issue which has caused problems across Britain and was of significance this quarter was the provision of accommodation for asylum seekers as well as the education of the children of asylum seekers. Though asylum is a retained matter, the issue has devolutionary dimension as education is a devolved matter. The other significant event was the challenge to John Swinney’s leadership of the Scottish National Party. A relatively unknown party activist challenged Swinney resulting in a drawn-out campaign over the Summer which culminated in a massive victory for Swinney at the SNP’s annual conference. -

Phases of Irish History

¥St& ;»T»-:.w XI B R.AFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY or ILLINOIS ROLAND M. SMITH IRISH LITERATURE 941.5 M23p 1920 ^M&ii. t^Ht (ff'Vj 65^-57" : i<-\ * .' <r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library • r m \'m^'^ NOV 16 19 n mR2 51 Y3? MAR 0*1 1992 L161—O-1096 PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY ^.-.i»*i:; PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY BY EOIN MacNEILL Professor of Ancient Irish History in the National University of Ireland M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. so UPPER O'CONNELL STREET, DUBLIN 1920 Printed and Bound in Ireland by :: :: M. H. Gill &> Son, • • « • T 4fl • • • JO Upper O'Connell Street :: :: Dttblin First Edition 1919 Second Impression 1920 CONTENTS PACE Foreword vi i II. The Ancient Irish a Celtic People. II. The Celtic Colonisation of Ireland and Britain . • • • 3^ . 6i III. The Pre-Celtic Inhabitants of Ireland IV. The Five Fifths of Ireland . 98 V. Greek and Latin Writers on Pre-Christian Ireland . • '33 VI. Introduction of Christianity and Letters 161 VII. The Irish Kingdom in Scotland . 194 VIII. Ireland's Golden Age . 222 IX. The Struggle with the Norsemen . 249 X. Medieval Irish Institutions. • 274 XI. The Norman Conquest * . 300 XII. The Irish Rally • 323 . Index . 357 m- FOREWORD The twelve chapters in this volume, delivered as lectures before public audiences in Dublin, make no pretence to form a full course of Irish history for any period. -

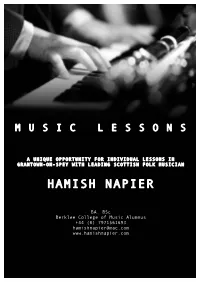

Here He Studied Jazz Piano and Composition

M U S I C L E S S O N S A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY FOR INDIVIDUAL LESSONS IN GRANTOWN-ON-SPEY WITH LEADING SCOTTISH FOLK MUSICIAN HAMISH NAPIER BA, BSc Berklee College of Music Alumnus +44 (0) 7971561693 [email protected] www.hamishnapier.com 1 of 4 Hello, I'm Hamish. I'm a professional musician, composer and music tutor. I'm delighted to announce that I will now be giving individual music lessons for one day a month in my home at Cherrygrove, Grantown- on-Spey. I have had enquiries from musicians from all over Scotland, as well as from the local area. My mother, Marie-Lousie Napier, taught piano and clàrsach pupils regularly at Cherrygrove for over 25 years. It's a special thing for me to continue this family tradition. If you are interested, or know somebody who might be, please get in touch. Please see below for more details. Many thanks, INSTRUMENTS Wooden flute Tin Whistle Piano Step-dancing (Scottish Cape Breton) I also teach students that play other instruments, focus on the student's general music skills. trad music accompaniment chords & harmony chart-writing improvisation music theory ear training music notation software keyboard skills ensemble skills tunesmithery & composition FEES & DETAILS 1 hr = £34 1.5 hrs = £48 2 hrs = £60 I am a member of the Musician’s Union and use MU rates. I have full public liability insurance. Students who are travelling greater distances have tended to opt for 2-hour lessons. Please note for a refund of lessons fees, cancellation must be made within 48 hours of lesson time. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

The Full Set of Programme Notes Can Be Downloaded from This Site. (Pdf)

www.junipergreen300.com 1707 St. Giles Bells Why should I be sad on my On the very day of the signing of the Treaty of Union wedding day [May 1707], the carillon player of St. Giles Cathedral mounted into his loft to give his daily hour-long recital. He played Scots, English, Irish and Italian tunes to great perfection. People used to stop and listen in the High Street. But on this day in 1707, knowing the whole city was listening and understanding his choice, the carilloner chose to play the most ironic musical gesture Scotland has ever known: Why should I be sad on my wedding day? 1757 Thomas Telford, the great engineer was born Bach-Short Mass Thomas Wilson Born Colorado, USA, but grew up in Glasgow area and studied music at Glasgow University, and in 1957 accepted a teaching post there. In 1971 he was appointed Reader and in 1977 given a personal Chair. His music is widely performed and broadcast, and includes the three-act opera, The Confessions of a Justified Sinner (Scottish Opera, 1974), four symphonies, several concertos, and a wide range of choral, chamber and instrumental works. In 1990 he was awarded the CBE, and the following year created Fellow of the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. Recent major works include his Guitar Concerto (Phillip Thorne, 1996), and his Symphony No 5 (Scottish Chamber Orchestra, 1998). 1807 Neil Gow, the great Scottish Fiddler died. Ca’ the Yowes/Ae Fond Kiss Marcus Blunt English by birth (Birmingham), and a University of Wales graduate, but resident in Scotland since 1990. -

January / February

CELTIC MUSIC • KENNY HALL • WORLD MUSIC • KIDS MUSIC • MEXICAN PAPER MAKING • CD REVIEWS FREE Volume 3 Number 1 January-February 2003 THE BI-MONTHLY NEWSPAPER ABOUT THE HAPPENINGS IN & AROUND THE GREATER LOS ANGELES FOLK COMMUNITY A Little“Don’t you know that Folk Music Ukulele is illegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEYof theWicket Tinkers is A Lot of Fun – a Beginner’s Tale BY MARY PAT COONEY t all started three workshop at UKE-topia hosted by Jim Beloff at years ago when I McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica. I was met Joel Eckhaus over my head in about 15 minutes, but I did at the Augusta learn stuff during the rest of the hour – I Heritage Festival just couldn’t execute any of it! But in Elkins, West my fear of chords in any key but I Virginia. The C was conquered. Augusta Heritage The concert that Festival is has been in existence evening was a for over 25 years, and produces delight with an annual 5-week festival of traditional music almost every uke and dance. Each week of the Festival specialist in the explores different styles, including Cajun, SoCal area on the bill. Irish, Old-Time, Blues, Bluegrass. The pro- The theme was old gram also features folk arts and crafts, espe- time gospel, in line with cially those of West Virginia. Fourteen years the subject of Jim’s latest ago Swing Week was instigated by Western book, and the performers that evening had Swing performers Liz Masterson and Sean quite a romp – some playing respectful Blackburn of Denver, CO as a program of gospel, and others playing whatever they music. -

The Book of Mormon in the English Literary Context of 1837

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 27 Issue 1 Article 5 1-1-1987 The Book of Mormon in the English Literary Context of 1837 Gordon K. Thomas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Thomas, Gordon K. (1987) "The Book of Mormon in the English Literary Context of 1837," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 27 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Thomas: The Book of Mormon in the English Literary Context of 1837 the book of mormon in the english literary context of 1837 gordon K thomas do you know anything of a wretched set of religionists in your country superstitionists I1 ought rather to say called mennonitesmormonitesmonnonitesMonnoMormonites or latter day saints so wrote the great english poet william wordsworth to his american editorhenryeditorhenry reed early in 1846 this is the only reference to mormonism in wordsworthsWord sworths surviving letters or other writings and it may come as a shock to modem latter day saints to find such anger and hostility towards us in a poet of whom we so often think as our poet one who believed much ofwhat we believe knew what we know and did not mind any more than we do defying the orthodox establishment of church and state -

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

The Scottish Nebraskan Newsletter of the Prairie Scots

The Scottish Nebraskan Newsletter of the Prairie Scots Chief’s Message Summer 2021 Issue I am delighted that summer is upon us finally! For a while there I thought winter was making a comeback. I hope this finds you all well and excited to get back to a more normal lifestyle. We are excited as we will finally get to meet in person for our Annual Meeting and Gathering of the Clans in August and hope you all make an effort to come. We haven't seen you all in over a year and a half and we are looking forward to your smiling faces and a chance to talk with all of you. Covid-19 has been rough on all of us; it has been a horrible year plus. But the officers of the Society have been meeting on a regular basis trying hard to keep the Society going. Now it is your turn to come and get involved once again. After all, a Society is not a society if we don't gather! Make sure to mark your calendar for August 7th, put on your best Tartan and we will see you then. As Aye, Helen Jacobsen Gathering of the Clans :an occasion when a large group of family or friends meet, especially to enjoy themselves e.g., Highland Games. See page 5 for info about our Annual Meeting & Gathering of the Clans See page 15 for a listing of some nearby Gatherings Click here for Billy Raymond’s song “The Gathering of the Clans” To remove your name from our mailing list, The Scottish Society of Nebraska please reply with “UNSUBSCRIBE” in the subject line. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2008 The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading Emily A. Cope University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cope, Emily A., "The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/348 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Emily A. Cope entitled "The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Dawn Coleman, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Janet Atwill, Martin Griffin Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Emily Ann Cope entitled “The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. -

Kenneth E. Querns Langley Doctor of Philosophy

Reconstructing the Tenor ‘Pharyngeal Voice’: a Historical and Practical Investigation Kenneth E. Querns Langley Submitted in partial fulfilment of Doctor of Philosophy in Music 31 October 2019 Page | ii Abstract One of the defining moments of operatic history occurred in April 1837 when upon returning to Paris from study in Italy, Gilbert Duprez (1806–1896) performed the first ‘do di petto’, or high c′′ ‘from the chest’, in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. However, according to the great pedagogue Manuel Garcia (jr.) (1805–1906) tenors like Giovanni Battista Rubini (1794–1854) and Garcia’s own father, tenor Manuel Garcia (sr.) (1775–1832), had been singing the ‘do di petto’ for some time. A great deal of research has already been done to quantify this great ‘moment’, but I wanted to see if it is possible to define the vocal qualities of the tenor voices other than Duprez’, and to see if perhaps there is a general misunderstanding of their vocal qualities. That investigation led me to the ‘pharyngeal voice’ concept, what the Italians call falsettone. I then wondered if I could not only discover the techniques which allowed them to have such wide ranges, fioritura, pianissimi, superb legato, and what seemed like a ‘do di petto’, but also to reconstruct what amounts to a ‘lost technique’. To accomplish this, I bring my lifelong training as a bel canto tenor and eighteen years of experience as a classical singing teacher to bear in a partially autoethnographic study in which I analyse the most important vocal treatises from Pier Francesco Tosi’s (c.