Miscellany Presented to Kuno Meyer by Some of His Friends and Pupils On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Kommunestrukturutredning Snillfjord, Hitra Og Frøya Delrapport 2 Om Bærekraftige Og Økonomisk Robuste Kommuner Anja Hjelseth Og Audun Thorstensen

Kommunestrukturutredning Snillfjord, Hitra og Frøya Delrapport 2 om bærekraftige og økonomisk robuste kommuner Anja Hjelseth og Audun Thorstensen TF-notat nr. 51/2015 1 Kolofonside Tittel: Kommunestrukturutredning Snillfjord, Hitra og Frøya Undertittel: Delrapport 2 om bærekraftige og økonomisk robuste kommuner TF-notat nr.: 51/2015 Forfatter(e): Audun Thorstensen og Anja Hjelseth Dato: 15.09.2015 ISBN: 978-82-7401-841-9 ISSN: 1891-053X Pris: (Kan lastes ned gratis fra www.telemarksforsking.no) Framsidefoto: Telemarksforsking og istockfoto.com Prosjekt: Utredning av kommunestruktur på Nordmøre Prosjektnummer.: 20150650 Prosjektleder: Anja Hjelseth Oppdragsgiver(e): Snillfjord, Hitra og Frøya kommuner Spørsmål om dette notatet kan rettes til: Telemarksforsking, Postboks 4, 3833 Bø i Telemark – tlf. 35 06 15 00 – www.telemarksforsking.no 2 Forord • Telemarksforsking har fått i oppdrag fra Hitra, Frøya og Snillfjord kommuner å utrede sammenslåing av de tre kommunene. Det skal leveres 5 delrapporter med følgende tema: – Helhetlig og samordnet samfunnsutvikling – Bærekraftige og økonomisk robuste kommuner – Gode og likeverdige tjenester – Styrket lokaldemokrati – Samlet vurdering av fordeler og ulemper ved ulike strukturalternativer • I tillegg til dette alternativet, så inngår Hitra og Snillfjord i utredningsalternativer på Nordmøre, hvor også Telemarksforsking står for utredningsarbeidet. Disse er: – Hemne, Hitra, Aure, Smøla og Halsa – Hemne, Aure, Halsa og Snillfjord • Denne delrapporten omhandler bærekraftige og økonomisk robuste kommuner. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

Poetry and Poems

Poetry Kaleidoscope Nicolae Sfetcu Published by Nicolae Sfetcu Second Edition Copyright 2014 Nicolae Sfetcu BOOK PREVIEW 1 Poetry Poetry (ancient Greek: ποιεω (poieo) = I create) is traditionally a written art form (although there is also an ancient and modern poetry which relies mainly upon oral or pictorial representations) in which human language is used for its aesthetic qualities in addition to, or instead of, its notional and semantic content. The increased emphasis on the aesthetics of language and the deliberate use of features such as repetition, meter and rhyme, are what are commonly used to distinguish poetry from prose, but debates over such distinctions still persist, while the issue is confounded by such forms as prose poetry and poetic prose. Some modernists (such as the Surrealists) approach this problem of definition by defining poetry not as a literary genre within a set of genres, but as the very manifestation of human imagination, the substance which all creative acts derive from. Poetry often uses condensed form to convey an emotion or idea to the reader or listener, as well as using devices such as assonance, alliteration and repetition to achieve musical or incantatory effects. Furthermore, poems often make heavy use of imagery, word association, and musical qualities. Because of its reliance on "accidental" features of language and connotational meaning, poetry is notoriously difficult to translate. Similarly, poetry's use of nuance and symbolism can make it difficult to interpret a poem or can leave a poem open to multiple interpretations. It is difficult to define poetry definitively, especially when one considers that poetry encompasses forms as different as epic narratives and haiku. -

On the Laws and Practice of Horse Racing

^^^g£SS/^^ GIFT OF FAIRMAN ROGERS. University of Pennsylvania Annenherg Rare Book and Manuscript Library ROUS ON RACING. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/onlawspracticeOOrous ON THE LAWS AND PRACTICE HORSE RACING, ETC. ETC. THE HON^T^^^ ADMIRAL ROUS. LONDON: A. H. BAILY & Co., EOYAL EXCHANGE BUILDINGS, COENHILL. 1866. LONDON : PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET, AND CHAKING CROSS. CONTENTS. Preface xi CHAPTER I. On the State of the English Turf in 1865 , . 1 CHAPTER II. On the State of the La^^ . 9 CHAPTER III. On the Rules of Racing 17 CHAPTER IV. On Starting—Riding Races—Jockeys .... 24 CHAPTER V. On the Rules of Betting 30 CHAPTER VI. On the Sale and Purchase of Horses .... 44 On the Office and Legal Responsibility of Stewards . 49 Clerk of the Course 54 Judge 56 Starter 57 On the Management of a Stud 59 vi Contents. KACma CASES. PAGE Horses of a Minor Age qualified to enter for Plates and Stakes 65 Jockey changed in a Race ...... 65 Both Jockeys falling abreast Winning Post . 66 A Horse arriving too late for the First Heat allowed to qualify 67 Both Horses thrown—Illegal Judgment ... 67 Distinction between Plate and Sweepstakes ... 68 Difference between Nomination of a Half-bred and Thorough-bred 69 Whether a Horse winning a Sweepstakes, 23 gs. each, three subscribers, could run for a Plate for Horses which never won 50^. ..... 70 Distance measured after a Race found short . 70 Whether a Compromise was forfeited by the Horse omitting to walk over 71 Whether the Winner distancing the Field is entitled to Second Money 71 A Horse objected to as a Maiden for receiving Second Money 72 Rassela's Case—Wrong Decision ... -

R.S. Thomas: Poetic Horizons

R.S. Thomas: Poetic Horizons Karolina Alicja Trapp Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 The School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis engages with the poetry of R.S. Thomas. Surprisingly enough, although acclaim for Thomas as a major figure on the twentieth century’s literary scene has been growing perceptibly, academic scholarship has not as yet produced a full-scale study devoted specifically to the poetic character of Thomas’s writings. This thesis aims to fill that gap. Instead of mining the poetry for psychological, social, or political insights into Thomas himself, I take the verse itself as the main object of investigation. My concern is with the poetic text as an artefact. The main assumption here is that a literary work conveys its meaning not only via particular words and sentences, governed by the grammar of a given language, but also through additional artistic patterning. Creating a new set of multi-sided relations within the text, this “supercode” leads to semantic enrichment. Accordingly, my goal is to scrutinize a given poem’s artistic organization by analysing its component elements as they come together and function in a whole text. Interpretations of particular poems form the basis for conclusions about Thomas’s poetics more generally. Strategies governing his poetic expression are explored in relation to four types of experience which are prominent in his verse: the experience of faith, of the natural world, of another human being, and of art. -

LANGUAGE Dictionaries 378 Dinneen, Patrick Stephen. an Irish-English

LANGUAGE Dictionaries 378 Dinneen, Patrick Stephen. An Irish-English dictionary, being thesaurus of the words, phrases and idioms of the modern Irish language. New ed., rev. and greatly enl. Dublin: 1927. 1340 p. List of Irish texts society's publications, etc.: 6 p. at end. A 2d edition which expanded the meanings and applications of key words, somatic terms and other important expressions. Contains words, phrases and idioms, of the modern Irish language. This, like other books published before 1948, is in the old spelling. 379 McKenna, Lambert Andrew Joseph. English-Irish dictionary. n.p.: 1935. xxii, 1546 p. List of sources: p. xv-xxii. Does not aim at giving all Irish equivalents for all English words, but at providing help for those wishing to write modern Irish. Places under the English head-word not only the Irish words which are equivalent, but also other Irish phrases which may be used to express the concept conveyed by the headword. Presupposes a fair knowledge of Irish, since phrases are used for illustration. Irish words are in Irish characters. ` Grammars 380 Dillon, Myles. Teach yourself Irish, by Myles Dillon and Donncha O Croinin. London: 1962. 243 p. Based on the dialect of West Munster, with purely dialect forms marked in most cases. Devotes much attention to important subject of idiomatic usages, but also has a thorough account of grammar. The book suffers from overcrowding, due to its compact nature, and from two other defects: insufficient sub-headings, and scant attention to pronunciation. 381 Gill, William Walter. Manx dialect, words and phrases. London: 1934. -

The Kennel Club Registration Printed: 22/09/2020 11:19:37 Prcd-PRA Tests September 2020 Page: 1 of 122

Report: r_dna_test The Kennel Club Registration Printed: 22/09/2020 11:19:37 prcd-PRA Tests September 2020 Page: 1 of 122 Below is a list of Kennel Club registered dogs of the breed specified above, together with their sire and dam, giving the date that they were DNA tested for the recessively inherited disease specified above. The result of the test can be either CLEAR (no copies of the mutant gene), CARRIER (one copy of the mutant gene) or AFFECTED (two copies of the mutant gene). Note that the progeny of a clear sire and clear dam will also be clear (hereditarily clear), and the progeny of two hereditarily clear, or one hereditarily clear and one tested clear dog will also be hereditarily clear. Further information on this scheme can be obtained from The Kennel Club Dog Name Reg/Stud No DOB Sex Sire Dam Test Date Result BREED: RETRIEVER (LABRADOR) A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S EL TORO AT BALLADOOLE 0213DF 27/08/2017 D BLACKSUGAR LUIS (ATCAQ02385BEL) WATERLINE'S SELLERIA 27/11/2018 CLEAR (IMP DEU) A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S GET LUCKY (IMP DEU) 0987DF 09/04/2018 D CLEARCREEK BONAVENTURE WINDSOCK A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S TEA FOR TWO (IMP DEU) 27/11/2018 CLEAR A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S I'M A JOKER 11/03/2010 D CARPENNY SCENARIO COCO LOCO'S TEA CUP 30/01/2011 CLEAR (ATCAP00538DEU) A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S TEA FOR TWO (IMP DEU) 0162DB 13/03/2014 B TIME SQUARE ULYSSES COCO LOCO'S TEA CUP 11/07/2016 CLEAR AARDVAR HOLLIS AQ01367904 09/04/2013 B ICYRIVERS MYOHMY BY CARRIEGAME AARDVAR GRANT 27/09/2013 CLEAR AARDVAR LANCASTER 0496CW 19/12/2009 D LUDALOR LUNAR ECLIPSE -

Norway Maps.Pdf

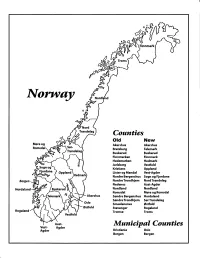

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Pdf Shop 'Celtic Gold' in Peel

No. 129 Spring 2004/5 €3.00 Stg£2.50 • SNP Election Campaign • ‘Property Fever’ on Breizh • The Declarationof the Bro Gymraeg • Istor ar C ’herneveg • Irish Language News • Strategy for Cornish • Police Bug Scandal in Mann • EU Constitution - Vote No! ALBA: COM.ANN CEILTFACH * BREIZH: KFVTCF KELT1EK * CYMRU: UNDEB CELTA DD * EIRE: CON RAD H GEILTE AC H * KERNOW: KtBUNYANS KELTEK * MANNIN: COMlVbtYS CELTIAGH tre na Gàidhlig gus an robh e no I a’ dol don sgoil.. An sin bhiodh a’ huile teasgag tre na Gàidhlig air son gach pàiste ann an Alba- Mur eil sinn fhaighinn sin bidh am Alba Bile Gàidhlig gun fheum. Thuig Iain Trevisa gun robh e feumail sin a dhèanamh. Seo mar a sgrìohh e sa bhli adhna 1365, “...dh’atharraich Iain à Còm, maighstir gramair, ionnsachadh is tuigsinn gramair sna sgoiltean o’n Fhraingis gu TEACASG TRE NA GÀIDHLIG Beurla agus dh’ionnsaich Richard Pencrych an aon scòrsa theagaisg agus Abajr gun robh sinn toilichte cluinntinn Inbhirnis/Inverness B IVI 1DR... fon feadhainn eile à Pencrych; leis a sin, sa gun bidh faclan Gaidhlig ar na ceadan- 01463-225 469 e-mail [email protected] bhliadhna don Thjgheama Againn” 1385, siubhail no passports again nuair a thig ... tha cobhair is fiosrachadh ri fhaighinn a an naodhamh bliadhna do’n Righ Richard ceann na bliadhna seo no a dh’ aithgheor thaobh cluich sa Gàidhlig ro aois dol do an dèidh a’Cheannsachaidh anns a h-uile 2000. Direach mar a tha sinn a’ dol thairis sgoil, Bithidh an t-ughdar is ionadail no sgoil gràmair feadh Sasunn, tha na leana- air Caulas na Frainge le bata no le trean -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: an Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions

Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: An Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions by Anna Wright BMus, Edinburgh Napier University, 2015 MMus, University of British Columbia, 2018 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Ethnomusicology) The University of British Columbia (Vancouver) April 2020 © Anna Wright, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: An Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions submitted by Anna Wright in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Ethnomusicology Examining Committee: Nathan Hesselink Supervisor, Chair, Ethnomusicology Department, School of Music, UBC Michael Tenzer Supervisory Committee Member, Professor, Ethnomusicology Department, School of Music, UBC ii Abstract This thesis examines the use of seist chorus sections in the Scottish Gaelic song tradition. These sections consist of nonsense syllables, or vocables. Although lacking semantic meaning, such vocables often provoke the joining in of the audience or listening group. The use of these vocable sections can be seen to have evolved in both their physical (sonic) characteristics and their social use and function over time while still maintaining a marked presence in Scottish Gaelic music across many genres and generations. I briefly examine theories surrounding seist vocables’ inception, interview three practitioners of Gaelic song about seist choruses’ inception and evolving function, examine four songs dating from a period spanning 1601-2016, and relate my findings to Scotland’s constantly evolving social and political climate.