R.S. Thomas: Poetic Horizons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LIVING CHURCH Is Published by the Living Church Foundation

Income from Church Property TLC Partners Theology of the Prayer Book February 12, 2017 THE LIV ING CHURCH CATHOLIC EVANGELICAL ECUMENICAL Prayer & Protest $5.50 livingchurch.org Architecture THE LIVING ON THE COVER HURCH Presiding Bishop Michael Curry: “I C pray for the President in part because THIS ISSUE February 12, 2017 Jesus Christ is my Savior and Lord. If | Jesus is my Lord and the model and guide for my life, his way must be my NEWS way, however difficult” (see “Prayer, 4 Prayer, Protest Greet President Trump Protest Greet President Trump,” p. 4). 6 Objections to Consecration in Toronto Danielle E. Thomas photo 10 Joanna Penberthy Consecrated 6 FEATURES 13 Property Potential: More Churches Consider Property Redevelopment to Survive and Thrive By G. Jeffrey MacDonald 16 NECESSARy OR ExPEDIENT ? The Book of Common Prayer (2016) | By Kevin J. Moroney BOOKS 18 The Nicene Creed: Illustrated and Instructed for Kids Review by Caleb Congrove ANNUAL HONORS 13 19 2016 Living Church Donors OTHER DEPARTMENTS 24 Cæli enarrant 26 Sunday’s Readings LIVING CHURCH Partners We are grateful to Church of the Incarnation, Dallas [p. 27], and St. John’s Church, Savannah [p. 28], whose generous support helped make this issue possible. THE LIVING CHURCH is published by the Living Church Foundation. Our historic mission in the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion is to seek and serve the Catholic and evangelical faith of the one Church, to the end of visible Christian unity throughout the world. news | February 12, 2017 Prayer, Protest Greet President Trump The Jan. 20 inauguration of Donald diversity of views, some of which have Trump as the 45th president of the been born in deep pain,” he said. -

Advent Poems to Ponder07.P65

○○○○ ADVENT POETRY COMPANION ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Advent Poetry Companion: Poems for Prayer and Pondering How to pray with poetry Using poetry as a companion for prayer can be a rich and engaging endeavor. Poetry as an art form uses the cadences of the spoken word, the nuances of language, the signals of punctuation and the employment of metaphors to invite the listener into participation in the unfolding of layers of meaning. Words can provide a bridge to experiences that are beyond words. “Prepare in the This Advent, we have prepared an Advent Poetry Companion which offers an additional resource for your Advent journey. This companion provides poems wilderness a that can enrich and deepen the meaning of this liturgical season. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ The prayers and liturgical readings of the Advent season are rich in meaning, symbolism, and prophetic themes. Poetry provides a beautiful way to explore highway for our and express these themes and probe more deeply the mystery of the incarna- God.” tion. Below are some simple suggestions for engaging poetry as a means of leading -Isaiah 40:3 you into prayer: 1. Seek a quiet space where you can minimize interruptions and take a few moments to enter into the silence. Let yourself sink deeply into the quiet. Invite God in. 2. Read just the title of the poem and ponder what this encounter might be about. 3. Read the poem aloud. Pay attention to the words, the sounds, the punctuation and what you are hearing in the poem. 4. Now read the poem silently and slowly letting the poem reveal new truths. -

Summer 2006 Shakespeare Matters Page 1

Summer 2006 Shakespeare Matters page 1 5:4 "Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments..." Summer 2006 “Stars or Suns:” The Portrayal of the Earls of Oxford in Elizabethan Drama By Richard Desper, PhD n Act III Scene vii of King Henry V, the proud nobles of France, gathered in camp on the eve of the battle of Agincourt, I speculate in anticipation of victory, letting their thoughts and their words take flight in fancy. While viewing the bedraggled English army as doomed, they savor their expected victory on the morrow and vie with each other in proclaiming their own glory. The dauphin1 boasts of his horse as another Pegasus, leading to a few allusions of a bawdy nature, and then a curious exchange takes place between Lord Rambures and the Constable of France, Professor William Leahy explains plans for a Shakespeare Charles Delabreth: Authorship Studies Master’s Program at Brunel University. Photo by William Boyle. Ram. My Lord Constable, the armor that I saw in your tent to-night, are those stars or suns upon it? Con. Stars, my lord. Brunel University to Offer 2 (Henry V, III.vii.63-5) Masters in Authorship Studies Shakespeare scholars have remarked little on these particular speeches, by default implying that they are words spoken in hile Concordia University has encouraged study of the passing, having no particular meaning other than idle chatter. Shakespeare authorship issue for years, Brunel One can count at least a dozen treatises on the text of Henry V that W University in England now plans to offer a graduate have nothing at all to say about these two lines.3 Yet numerous program leading to an M.A. -

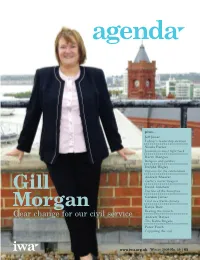

Gill Morgan, Is Dealing with Whitehall Arrogance

plus… Jeff Jones Labour’s leadership election Nicola Porter Journalism must fight back Barry Morgan Religion and politics Dafydd Wigley Options for the referendum Andrew Shearer Garlic’s secret weapon Gill David Culshaw Decline of the honeybee Gordon James Coal in a warm climate Morgan Katija Dew Beating the crunch Gear change for our civil service Andrew Davies The Kafka Brigade Peter Finch Capturing the soul www.iwa.org.uk Winter 2009 No. 39 | £5 clickonwales ! Coming soon, our new website www. iwa.or g.u k, containing much more up-to-date news and information and with a freshly designed new look. Featuring clickonwales – the IWA’s new online service providing news and analysis about current affairs as it affects our small country. Expert contributors from across the political spectrum will be commissioned daily to provide insights into the unfolding drama of the new 21 st Century Wales – whether it be Labour’s leadership election, constitutional change, the climate change debate, arguments about education, or the ongoing problems, successes and shortcomings of the Welsh economy. There will be more scope, too, for interactive debate, and a special section for IWA members. Plus: Information about the IWA’s branches, events, and publications. This will be the must see and must use Welsh website. clickonwales and see where it takes you. clickonwales and see how far you go. The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges core funding from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust , the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation . The following organisations are corporate members: Private Sector • Principality Building Society • The Electoral Commission Certified Accountants • Abaca Ltd • Royal Hotel Cardiff • Embassy of Ireland • Autism Cymru • Beaufort Research • Royal Mail Group Wales • Fforwm • Cartrefi Cymunedol / • Biffa Waste Services Ltd • RWE NPower Renewables • The Forestry Commission Community Housing Cymru • British Gas • S. -

SEDULIUS, the PASCHAL SONG and HYMNS Writings from the Greco-Roman World

SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Writings from the Greco-Roman World David Konstan and Johan C. ! om, General Editors Editorial Board Brian E. Daley Erich S. Gruen Wendy Mayer Margaret M. Mitchell Teresa Morgan Ilaria L. E. Ramelli Michael J. Roberts Karin Schlapbach James C. VanderKam Number 35 SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Volume Editor Michael J. Roberts SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Carl P. E. Springer Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Copyright © 2013 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions O! ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sedulius, active 5th century. The Paschal song and hymns / Sedulius ; translated with an introduction >and notes by Carl P. E. Springer. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature. Writings from the Greco-Roman world ; volume 35) Text in Latin and English translation on facing pages; introduction and >notes in English. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-743-0 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-744-7 (electronic format) — ISBN 978-1-58983-768-3 (hardcover binding : alk. -

Poetry and Poems

Poetry Kaleidoscope Nicolae Sfetcu Published by Nicolae Sfetcu Second Edition Copyright 2014 Nicolae Sfetcu BOOK PREVIEW 1 Poetry Poetry (ancient Greek: ποιεω (poieo) = I create) is traditionally a written art form (although there is also an ancient and modern poetry which relies mainly upon oral or pictorial representations) in which human language is used for its aesthetic qualities in addition to, or instead of, its notional and semantic content. The increased emphasis on the aesthetics of language and the deliberate use of features such as repetition, meter and rhyme, are what are commonly used to distinguish poetry from prose, but debates over such distinctions still persist, while the issue is confounded by such forms as prose poetry and poetic prose. Some modernists (such as the Surrealists) approach this problem of definition by defining poetry not as a literary genre within a set of genres, but as the very manifestation of human imagination, the substance which all creative acts derive from. Poetry often uses condensed form to convey an emotion or idea to the reader or listener, as well as using devices such as assonance, alliteration and repetition to achieve musical or incantatory effects. Furthermore, poems often make heavy use of imagery, word association, and musical qualities. Because of its reliance on "accidental" features of language and connotational meaning, poetry is notoriously difficult to translate. Similarly, poetry's use of nuance and symbolism can make it difficult to interpret a poem or can leave a poem open to multiple interpretations. It is difficult to define poetry definitively, especially when one considers that poetry encompasses forms as different as epic narratives and haiku. -

Tethys Festival As Royal Policy

‘The power of his commanding trident’: Tethys Festival as royal policy Anne Daye On 31 May 1610, Prince Henry sailed up the River Thames culminating in horse races and running at the ring on the from Richmond to Whitehall for his creation as Prince of banks of the Dee. Both elements were traditional and firmly Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester to be greeted historicised in their presentation. While the prince is unlikely by the Lord Mayor of London. A flotilla of little boats to have been present, the competitors must have been mem- escorted him, enjoying the sight of a floating pageant sent, as bers of the gentry and nobility. The creation ceremonies it were, from Neptune. Corinea, queen of Cornwall crowned themselves, including Tethys Festival, took place across with pearls and cockleshells, rode on a large whale while eight days in London. Having travelled by road to Richmond, Amphion, wreathed with seashells, father of music and the Henry made a triumphal entry into London along the Thames genius of Wales, sailed on a dolphin. To ensure their speeches for the official reception by the City of London. The cer- carried across the water in the hurly-burly of the day, ‘two emony of creation took place before the whole parliament of absolute actors’ were hired to play these tritons, namely John lords and commons, gathered in the Court of Requests, Rice and Richard Burbage1 . Following the ceremony of observed by ambassadors and foreign guests, the nobility of creation, in the masque Tethys Festival or The Queen’s England, Scotland and Ireland and the Lord Mayor of Lon- Wake, Queen Anne greeted Henry in the guise of Tethys, wife don with representatives of the guilds. -

Actes Des Congrès De La Société Française Shakespeare, 36 | 2018 “The Dread of Something After Death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of S

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 36 | 2018 Shakespeare et la peur “The dread of something after death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of Shakespearean Revenants Christy Desmet Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/4018 DOI: 10.4000/shakespeare.4018 ISSN: 2271-6424 Publisher Société Française Shakespeare Electronic reference Christy Desmet, ““The dread of something after death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of Shakespearean Revenants”, Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare [Online], 36 | 2018, Online since 22 January 2018, connection on 25 August 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ shakespeare/4018 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/shakespeare.4018 This text was automatically generated on 25 August 2021. © SFS “The dread of something after death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of S... 1 “The dread of something after death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of Shakespearean Revenants Christy Desmet 1 Contemplating suicide, or more generally, the relative merits of existence and non- existence, Hamlet famously asks: Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country from whose bourn No traveler returns, puzzles the will And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of. (Hamlet, 3.1.84-90, emphasis added)1 Critics have complained that Hamlet knows right well what happens after death, as is made clear by the earlier account of his father, who is Doomed for a certain term to walk the night And for the day confined to fast in fires Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature Are burnt and purged away. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Apostolic Discourse and Christian Identity in Anglo-Saxon Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository APOSTOLIC DISCOURSE AND CHRISTIAN IDENTITY IN ANGLO-SAXON LITERATURE BY SHANNON NYCOLE GODLOVE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles D. Wright, Chair Associate Professor Renée Trilling Associate Professor Robert W. Barrett Professor Emerita Marianne Kalinke ii ABSTRACT “Apostolic Discourse and Christian Identity in Anglo-Saxon Literature” argues that Anglo-Saxon religious writers used traditions about the apostles to inspire and interpret their peoples’ own missionary ambitions abroad, to represent England itself as a center of religious authority, and to articulate a particular conception of inspired authorship. This study traces the formation and adaptation of apostolic discourse (a shared but evolving language based on biblical and literary models) through a series of Latin and vernacular works including the letters of Boniface, the early vitae of the Anglo- Saxon missionary saints, the Old English poetry of Cynewulf, and the anonymous poem Andreas. This study demonstrates how Anglo-Saxon authors appropriated the experiences and the authority of the apostles to fashion Christian identities for members of the emerging English church in the seventh and eighth centuries, and for vernacular religious poets and their readers in the later Anglo-Saxon period. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to many people for their help and support throughout the duration of this dissertation project. -

Rędende Iudithše: the Heroic, Mythological and Christian Elements in the Old English Poem Judith

University of San Diego Digital USD Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses and Dissertations Fall 12-22-2015 Rædende Iudithðe: The eH roic, Mythological and Christian Elements in the Old English Poem Judith Judith Caywood Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/honors_theses Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Digital USD Citation Caywood, Judith, "Rædende Iudithðe: The eH roic, Mythological and Christian Elements in the Old English Poem Judith" (2015). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 15. https://digital.sandiego.edu/honors_theses/15 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rædende Iudithðe: The Heroic, Mythological and Christian Elements in the Old English Poem Judith ______________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty and the Honors Program Of the University of San Diego ______________________ By Jude Caywood Interdisciplinary Humanities 2015 Caywood 2 Judith is a character born from the complex multicultural forces that shaped Anglo-Saxon society, existing liminally between the mythological, the heroic and the Christian. Simultaneously Germanic warrior, pagan demi-goddess or supernatural figure, and Christian saint, Judith arbitrates amongst the seemingly incompatible forces that shaped the poet’s world, allowing the poem to serve as an important site for the making of a new Anglo-Saxon identity, one which would eventually come to be the united English identity. She becomes a single figure who is able to reconcile these opposing forces within herself and thereby does important cultural work for the world for which the poem was written. -

Title Author Category

TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY A An Invitation to Joy - John Paul II Burke, Greg Popes Abbey Psalter, The - Trappist Monks Paulist Press Religious Orders An Outline of American Philosophy Bentley, John E. Philosophy ABC's of Angels, The Gates, Donna S. Teachings for Children An Unpublished Manuscript on Purgatory Society of the IHOM Faith and Education ABC's of the Ten Commandments, The O'Connor, Francine M. Teachings for Children Anatomy of the Spirit Myss, Caroline, PhD Healing Abraham Feiler, Bruce Saints And The Angels Were Silent Lucado, Max Inspirational Accessory to Murder Terry, Randall A. Reference And We Shall Cast Rainbows Upon The Land Reitze, Raymond Spirituality Acropolis of Athens, The Al. N. Oekonomides Arts and Travel Angel Book, The Goldman, Karen Angels Acts Holman Reference Bible Reference Angel Letters Burnham, Sophy Angels Acts - A Devotional Commentary Zanchettin, Leo, Gen. Ed. Books of the Bible Angel Talk Crystal, Ruth Angels Acts of Kindness McCarty Faith and Education Angels Bussagli, Mario Angels Acts of the Apostles Barclay, William Books of the Bible Angels & Demons Kreeft, Peter Angels Acts of The Apostles Hamm, Dennis Books of the Bible Angels & Devils Cruse, Joan Carroll Angels Acts of the Apostles - Study Guide Little Rock Scripture Books of the Bible Angels and Miracles Am. Bible Society Angels Administration of Communion and Viaticum US Catholic Conference Reference Angels of God Aquilina, Mike Angels Advent and Christmas - St. Francis Assisi Kruse, John V., Compiled St. Francis of Assisi Angels of God Edmundite Missions Angels Advent and Christmas with Fr. Fulton Sheen Ed. Bauer, Judy Liturgical Seasons Anima Christi - Soul of Christ Mary Francis, Mother, PCC Jesus Advent Thirst … Christmas Hope Constance, Anita M., SC Liturgical Seasons Annulments and the Catholic Church Myers, Arhbishop John J., b.b.