1 Two Decades of Ideological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Professionalisation of the Indonesian Military

The Professionalisation of the Indonesian Military Robertus Anugerah Purwoko Putro A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences July 2012 STATEMENTS Originality Statement I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Copyright Statement I hereby grant to the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I retain all property rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Authenticity Statement I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. -

Plagiat Merupakan Tindakan Tidak Terpuji

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERUBAHAN BADAN KEAMANAN RAKYAT MENJADI TENTARA NASIONAL INDONESIA DARI TAHUN 1945-1948 MAKALAH Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Disusun oleh: Geovani Louisa Gospa Cotera NIM: 101314012 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2014 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI MOTTO † Untuk segala sesuatu ada waktunya Ia membuat segala sesuatu indah pada waktunya, bahkan Ia memberikan kekekalan dalam hati mereka. (Pengkotbah Pasal 3) † Dan apa saja yang kamu minta dalam doa dengan penuh kepercayaan, kamu akan menerimanya. (Matius 21:22) † Setiap pencapaian yang bermanfaat, besar atau kecil, memiliki tahap yang membosankan dan keberhasilan: sebuah permulaan, sebuah perjuangan dan sebuah kemenangan. (Mahatma Gandhi) iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERSEMBAHAN Makalah ini saya persembahkan kepada: Tuhan Yesus Kristus dan Bunda Maria teladanku yang senantiasa mendampingi dan melindungiku dalam setiap langkah hidupku. Kedua orang tuaku Bapak Sutejo Simon dan Ibu Corona Nian Sari yang selalu memberiku perhatian, dukungan, semangat, dan mendoakanku untuk berjuang demi masa depanku. Adikku Gema Yulenta Gospa Cotera yang selalau memberiku semangat. Natalio Haryogi yang selalu memberi semangat, dukungan dan doa. Saudara dan -

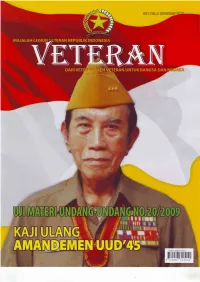

Vol L. No. 2. Desember

Voll. No.2. Desember VeteranMendambakan Damai karena Mengenal Perang -,p VrruRm Salam Redaksi Maialah Veteran No. 2. ini Daftar Isi diterbitkan dengantetap menjelaskan keadazn dan kegiztzn palr^ Veteran SalamRedaksi dan organisasinya Legiun Veteran Amandemen UUD'45 Harus Dikaji Ulang Republik Indonesia, di samping LVRI 54 Tahun menyampaikan pikiran-pikiran dan LVRI SiapkanUji Materi Undang-UndangNo.20l2009 11 hanpan-harapan p^ra Veteran. Pembantaianoleh NICA di TemanggungTahun 1948/1949 1,4 Sejarah Perjuangan Bangsa, baik Pertempuran di Bangka Belitung 18 pembant^t^nNICA di Temanggung, Pertempuran Margarana di Bali 21 Pertempuran di Bangka Belitung dan Desa Marga, Bali serta liputan LVRI Peringati Hari Pahlawan kegiatan-kegiatan dalam nngka Tali Asih untuk Veteran peringatan 10 Nopember 2010 Pahlawanitu ditenrukan oleh Sflaktudan Tempat dengan berbagzt m^c^m kegiatan Veterandalam Gambar 29 sosialnya merupakan beberapa di \Telcome Cambodia 33 antarany^. Lebih khusus adalah Konferensi InternasionalKe-7 WVF di Paris 36 mengenaiHUT LVRI ke-54. Medali WVF untuk D. Ashari 39 Sebagai harapan kami kepada Afganistan pembaca, apabtla mempunyai Hati yang Tenang catatan-catatan, i de-id e, p engalaman- 45 pengalaman atau-pun tulisan-tulisan Hidayat Tokoh di Balik PDRI y^ng bersifat perjuangan, sangat Obrolan Masalah ESB @konomi, Sosialdan Budaya) diharapkan untuk menambah isi HIPVI Tetap Eksis Majalah Veteran terbitan selanjutnya. Ragam Kehidupan Semoga majalah ini dapat SKEP Hymne Veteran memenuhiharapan pan pembaca. Hymne Veteran 55 Himawan Soetanto, Prajurit Kujang Asal Magetan, Telah Tiada 56 Redaksi Gugur Bunga PenerbitDEWAN PIMPINAN PUSAT LVRI, DPP LVRI . GedungVeteran Rl "GrahaPurna Yudha" Jl. Jenderal Sudirman Kav. 50 Jakarta12930 . Telp.(021 ) 5254105,5252449, 25536744 . Fax. (021 ) 5254137Pembinal PenasehatRais Abin - KetuaUmum DPP LVRI, Gatot Suwardi - Wakil KetuaUmum I DPPLVRI, HBL. -

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Masalah Perang

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Masalah Perang merupakan suatu duel atau pergulatan secara besar-besaran, masing-masing pihak mencoba memaksa pihak yang lain dengan kekuatan fisiknya untuk tunduk kepada kehendaknya. Dengan demikian maka perang adalah suatu tindakan kekerasan untuk memaksa musuh tunduk dan menuruti kehendaknya.1 Terdapat dua jenis perang yaitu perang konvensional dan perang non konvensional. Perang konvensional adalah perang secara langsung dan secara fisik, sementara perang non konvensional adalah perang tidak langsung dan nonfisik. Yang termasuk kategori perang Non-Konvensional, yaitu perang yang dilakukan dengan cara yang tidak sesuai dengan peraturan Konvensi Jenewa (serangkaian atauran untuk memperlakukan warga sipil, tawanan perang dan tentara yang berada dalam kondisi tidak mampu bertempur) adalah perang wilayah, perang teror, perang intelijen dan perang dunia kedua. Perang wilayah sendiri mulai berkembang dengan adanya guerrillya. Kata dalam bahasa Spanyol itu berarti “perang kecil”, yaitu cara perlawanan oleh satu kumpulan orang yang tidak mampu melakukan perlawanan militer yang normal terhadap kekuatan militer yang besar. Kata “guerrillya” itu kemudian dijadikan kata Indonesia menjadi “gerilya”.2 1 Makmur Supriyatno, Tentang Perang Bagian I Terjemahan “0n War” Carl Von Clausewitz (Jakarta: CV. Makmur Cahaya Ilmu: 2017) hal. 46-47. 2 Letjen TNI (purn) Sayidiman Suryohadiprojo, Pengantar Ilmu Perang (Jakarta: Pustaka Intermasa, 2008) hal. 108. 1 2 Gerilya adalah muncul-menghilang, mondar mandir di mana-mana, sehingga sulit dideteksi oleh musuh, tetapi dirasakan menyerang di mana saja. Gerilya adalah menyerang dengan tiba-tiba dan kemudian menghilang dengan cepat (hit and run).3 Perang gerilya sebenarnya bukan merupakan sebuah hal baru bagi perjuangan bangsa Indonesia. Bisa dilihat dari perang Diponegoro atau perang Jawa jilid II yang terjadi tahun 1825 sampai 1830, dan perang Aceh yang merupakan perang terlama melawan penjajah, yakni sejak tahun 1873 hingga 1904. -

Democratization and Political Succession in Suharto's Indonesia Author(S): Leo Suryadinata Source: Asian Survey, Vol

Democratization and Political Succession in Suharto's Indonesia Author(s): Leo Suryadinata Source: Asian Survey, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Mar., 1997), pp. 269-280 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2645663 Accessed: 15-09-2016 05:52 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Asian Survey This content downloaded from 175.45.185.255 on Thu, 15 Sep 2016 05:52:49 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms DEMOCRATIZATION AND POLITICAL SUCCESSION IN SUHARTO'S INDONESIA Leo Suryadinata Indonesia has often been described as an authoritarian state. The military, represented by General Suharto, has ruled the country since the 1965 coup. However, some observers maintain that in recent years the authoritarian regime appears to have been softening, evidenced by the weakening role of the Indonesian Armed Forces (ABRI) in the political pro- cess. President Suharto appointed fewer military personnel to his 1993 cabi- net and selected a civilian to be the general chairman of Golkar, the ruling party; he also reduced the military composition of Golkar at the national level and the number of military representatives (unelected) in the forthcoming Parliament (DPR). -

No. 8 Juni 2012

veteran Vol. 2 No. 8 Juni 2012 MAJALAHH LEGIUN VVETERANETERAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA veteran DARI VETERAN OLEH VETERAN UNTUK BANGSA DAN NEGARA pperlawananerlawanan tterhadaperhadap bbelandaelanda ddii kkalimantanalimantan sselatanelatan dua muka jan pieterszoon coen ppembantaianembantaian ddii llembahembah aanainai Vol. 2 No. 8 Juni 2012 1 veteran 2 Vol. 2 No. 8 Juni 2012 veteran Daftar Isi Salam Redaksi Daftar Isi Majalah Veteran Vol. 2 No. 8 Juni 2012 menampilkan tokoh Veteran daerah Salam Redaksi 3 sekaligus penerus cita - cita Ibu R. A. Hj. Noorma Ariatie Ketua DPD-LVRI Propinsi Kalsel 4 Kartini yaitu Ibu Hj. Noorma Ariatie Laporan Peringatan Harkitnas ke-104 6 Ketua DPD-LVRI Kalsel dan Ibu Putri Kaligis Ketua DPC-LVRI Batam. Perlawanan terhadap Belanda di Kalimantan Selatan 9 Edisi ini menyampaikan laporan Putri Kaligis Estafet Citra Kartini 13 Peringatan Harkitnas ke-104 di LVRI, Lintas Safari Perjalanan Juang Cikal Bakal TRIPS 16 juga kisah Perlawanan Rakyat Kalsel PKRI di mana Engkau 24 terhadap Belanda. Perjalanan Juang Cikal Bakal TRIPS Sejarah Website LVRI 26 masih dimuat secara bersambung, Veteran dalam Gambar 29 demikian juga perihal PKRI sebagai Jan Pieterszoon Coen Tumbang 34 informasi di sampaikan Sejarah Website LVRI. Pembantaian di Lembah Anai 36 Kisah heroik Pertempuran ALRI Beberapa Kegiatan LVRI di Pusat dan di Daerah 39 Pangkalan Pariaman, kisah pilu Pertempuran yang dilakukan oleh ALRI Pangkalan Pariaman 42 Pembantaian di Lembah Anai dipaparkan Peristiwa di Bagansiapiapi 45 pula. Pada akhir terbitan ini dikenang Ki Samsudin telah Tiada 47 kembali kiprah Ki Samsudin dan Pak Sayidiman Suryohadiprojo dianugerahi Bintang Jasa 50 Domo yang telah menghadap Sang Obituari - Laksamana TNI (Purn) Sudomo 51 Khalik. -

Bab 2 Perkembangan Fungsi Pembinaan Teritorial Satuan Komando Kewilayahan Tni Ad

BAB 2 PERKEMBANGAN FUNGSI PEMBINAAN TERITORIAL SATUAN KOMANDO KEWILAYAHAN TNI AD Bab 2 ini membahas perkembangan pelaksanaan fungsi pembinaan teritorial Satuan Kowil TNI AD dari tahun 1945 hingga tahun 2009. Pembahasan fungsi pembinaan teritorial Satuan Kowil TNI AD mencakup: (1) fungsi pembinaan teritorial sebagai perwujudan dari strategi perang semesta (total war); (2) fungsi pembinaan teritorial sebagai strategi pengelolaan potensi nasional; (3) fungsi pembinaan teritorial sebagai strategi penjaga stabilitas politik dan keamanan pemerintahan Orde Baru; (4) fungsi pembinaan teritorial sebagai pemberdayaan wilayah pertahanan di darat dan kekuatan pendukungnya secara dini untuk mendukung sistem pertahanan dan sistem pelawanan rakyat semesta. Pembahasan dimulai dari fungsi teritorial militer Belanda (KNIL) tahun 1830-1942 dan perang gerilya militer Jepang (PETA/Heiho) tahun 1942-1945 untuk melihat “benang merah” keterkaitan dengan pembentukan fungsi Satuan Kowil TNI AD. Sedangkan pelaksanaan fungsi pembinaan teritorial Satuan Kowil TNI AD dari masing-masing tahap pembentukannya sejak Komanden TKR hingga Satuan Kowil TNI AD dan konflik internal militer yang menyertainya merupakan inti pembahasan dari Sub-Bab 2 ini. 2.1. Komando Teritorial KNIL Koninklijk Nederlandsch Indische Leger (KNIL) merupakan badan militer resmi Kerajaan Belanda yang dibentuk pada tahun 1830 di Hindia Belanda.161 Tujuan pembentukan badan militer ini adalah untuk melaksanakan dua fungsi sekaligus (dwifungsi), yaitu: (1) fungsi militer untuk menjaga Hindia Belanda dari 161 Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger (KNIL) yang terbentuk pada 10 Maret 1830 adalah nama resmi Tentara Kerajaan Hindia-Belanda. Meskipun KNIL militer pemerintahan Hindia Belanda, tapi banyak para anggotanya merupakan penduduk pribumi. Di antara perwira yang memegang peranan penting dalam pengembangan dan kepemimpinan angkatan bersenjata Indonesia yang pernah rnenjadi anggota KNIL pada saat rnenjelang kemerdekaan adalah Oerip Soemohardjo, E. -

101 DAFTAR PUSTAKA Anderson, Curtis, A

DAFTAR PUSTAKA Anderson, Curtis, A Short History of Japan From Samurai to Sony, Australia: Allen & Unwin, 2002. Beasley, W.G, Pengalaman Jepang sejarah singkat Jepang, Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia,2003. Brinkley, Frank, A History of Japanese People, Japan: Blackmask, 2007. Bryant, Anthony J, Sekigahara 1600 The Final Struggle For Power, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2003. , The Samurai, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2000. Cullen,L.M, A History of Japan 1582-1941 (Internal and External Worlds), United States of Amerika: Cambridge University Press, (t.t). Deal, William. E, Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japana, New York: Fact On File, 2006. Hasan Shadiliy, Sosiologi untuk Masyarakat Indonesia. Jakarta: Bina Aksara, 1984. Henshall, Kenneth,G, A History of Japan From Stone Age to Superpower 2nd edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. Gottschalk, Louis, (a.b). Nugroho Notosusanto. Mengerti Sejarah. Jakarta: UI Press, 1985. Ishii, Ryosuke, History of Political Institutions in Japan, (a.b), J.R. Sunaryo, Sejarah Institusi Politik Jepang, Jakarta: Gramedia, 1989. Jansen, Marius B, The Making Modern Japan. England: Harvard University Press, 2000. Jeffrey P. Mass dan William B. Hauser, The Bakufu in Japanese History, California: Stanford University Press, 1985. Kuntowijoyo, Metodologi Sejarah Edisi Kedua,Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana, 2003. 101 , Pengantar Ilmu Sejarah. Yogyakarta: Bentang Budaya, 2005. Lataurette, K.S, A Short History of the Far East. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1957. , History of Japan, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1957. M.G, Harold, Japan an Economic and Finansial Appraisal. Washington,D.C: The Brookings Institutions,1931. Norton, J.L, Jepang Purba, Jakarta: Tira Pustaka, 1983. -

A Note on Military Organization 1. Marc Lohnstein, Royal Netherlands East Indies Army 1936–42 (Oxford: Osprey, 2018), P

Notes A Note on Military Organization 1. Marc Lohnstein, Royal Netherlands East Indies Army 1936–42 (Oxford: Osprey, 2018), p. 8. 2. J.J. Nortier, P. Kuijt and P.M.H. Groen, De Japanse aanval op Java, Maart 1942 (Amsterdam: De Bataafsche Leeuw, 1994), p. 305. 3. Lionel Wigmore, Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series One, Army, Volume IV, The Japanese Thrust (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1957), p. 445. Preface 1. In his speech, Soeharto said he wanted to pass on the facts “as far as we know them” concerning the situation “which we have all been experiencing and witnessing together” in connection with the September 30th Movement. For an English-language translation of the speech, which ran to some 6,000 words, see “Speech by Major-General Suharto on October 15, 1965, to Central and Regional Leaders of the National Front”, in The Editors, “Selected Documents Relating to the September 30th Movement and Its Epilogue”, Indonesia, Vol. 1 (April 1966), Cornell Modern Indonesia Project, at pp. 160–78. On the National Front, see Harold Crouch, The Army and Politics in Indonesia, rev. ed. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988), p. 34. Sukarno had at one stage privately told the American ambassador he saw the National Front as a vehicle through which he could create a one-party state. The parties successfully opposed the idea, however, and the front became a propaganda agency for the government, increasingly influenced by Communists. Howard Palfrey Jones, Indonesia: The Possible Dream, 4th ed. (Singapore: Gunung Agung, 1980), p. 245. 2. Interviews, Professor K.P.H. -

Javanese Culture As Guidance for Suharto's Personal Life and for His

Javanese Culture as Guidance for Suharto’s Personal Life and for His Rule of the Country Totok Sarsito Abstract Obedience to superiors or ’manut’, generosity, avoidance of conflict, understanding others, and empathy have been adopted by the Javanese as principle for their lives. Someone who does not understand these Javanese principles will be considered ’durung Jawa’ (not yet Javanese) or ’durung ngerti’ (does not yet understand) and they are eligible to be educated or punished. On the other hand, someone who understands well and takes these principles as guidance for his life will be safe and very much honored, appreciated and acceptable to be a leader. Therefore, someone who knows well about these principles of Javanese life will always try to be a true Javanese by adopting these Javanese teachings as guidance for his life and the practice of these teachings would give added values to his role and position in society. Suharto whose awareness on Javanese culture had grown up since he was young understood the above notion and had always been committed to honor and practice the teachings inherited by the Javanese ancestors. He adopted these noble Javanese cultural values and philosophy taught by the ancestors (some of them were in the form of ‘petatah-petitih’) as ‘pituduh’ or guidance and ‘wewaler’ or prohibition not only for his individual life but very often also for his rule of the country. Key words: ‘rukun’ or harmonious unity, ‘urmat’ or respect, ‘gotong royong’ or mutual assistance, ‘pituduh’ or guidance, ‘wewaler’ or prohibitions, Introduction For most Javanese “to be Javanese means to be a person who is civilized and who knows his manners and his place” (Geertz 1961; Mulder 1978; Koentjaraningrat 1985). -

The Indonesian Military Response to Reform in Democratic Transition: A

The Indonesian Military Response to Reform in Democratic Transition: A Comparative Analysis of Three Civilian Regimes 1998-2004 Inaugural - Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg im Breisgau im Seminar für Wissenschaftlicher Politik vorgelegt von Poltak Partogi Nainggolan Aus Jakarta, Indonesien Wintersemester 2010/2011 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Jürgen Rüland Zweigutachter: Prof. Dr. Heribert Weiland Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen, Philosophischen und Wirtschafts- und Verhaltenswissenschaftlichen Fakultaet: Prof. Dr. Hans-Helmut Gander Tag der Fachprüfung im Promotionsfach Politische Wissenschaft: 10 Februar 2011 This dissertation is dedicated to those who struggle for a better Indonesia and become the victims of reform Acknowledgements Having worked in an institution such as the Indonesian parliament (DPR) -- an important actor in the democratic transition in Indonesia -- and witnessed many important events during this period, I am encouraged to share with the public my knowledge and insights into what really happened. The unclear prospect of post-Soeharto reform and the chaotic situation caused by various conflicts throughout Indonesia have also motivated me to examine the response of the Indonesian military, which since the formation of the country has been viewed as the loyal guardian of the state. The idea for this dissertation came up in mid-2001, after the sudden fall of the first democratically elected civilian regime of Abdurrahman Wahid. However, the project could only begin in 2004 after I had received a positive response from the representative of the Hanns Seidel-Stiftung in Jakarta, Mr. Christian Hegemer, about my PhD scholarship for the study at Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg (University of Freiburg). -

92 BAB V KESIMPULAN Tentara Pelajar Yang Merupakan Salah Satu

BAB V KESIMPULAN Tentara pelajar yang merupakan salah satu unsur dari kekuatan Republik Indonesia ternyata pada masa Perang Kemerdekaan mempunyai peranan yang penting. Harus diakui bahwa gerakan pemuda (termasuk pelajar) pada saat Perang Kemerdekaan tampak menonjol. Hal ini karena adanya beberapa faktor dari luar maupun dalam. Faktor dari luar yaitu keadaan ekonomi, politik, sosial, terutama bidang pendidikan. Sedangkan faktor dari dalam yaitu perasaan nasionalisme, heroisme, idealism, dan petriotisme. Para pelajar yang kebanyakan setingkat sekolah menengah lanjutan memiiki semangat perjuangan yang besar. Rasa nasionalisme yang telah tertanam dalam jiwa bangsa Indonesia, terutama para pemuda yang ingin melepaskan diri dari segala macam penderitaan dari penjajahan menimbulkan kerelaan berkorban bagi bangsa yang telah menderita. Nilai-nilai patriotisme para pemuda mulai tumbuh dan semakin berkembang sejalan dengan beratnya penderitaan sebagai akibat penjajahan itu. Puncak dari semuanya yaitu keinginan untuk melawan segala macam praktek penindasan dan penjajahan. Faktor di atas dapat dikatakan berpengaruh secara tidak langsung terhadap para pelajar. Selain itu juga timbulnya kesadaran akan kemerdekaan yang berjiwa nasional serta diiringi dengan semangat dan keberanian untuk mewujudkan harapan bangsanya membuat mereka melawan semua bentuk penjajahan. Pelajar pejuang yang masih muda, yang berumur 15-22 tahun dengan modal ketrampilan dasar kemiliteran yang pernah diberikan pada masa Jepang ikut memberi sumbangan praktis, sehingga mempercepat berdirinya organisasi 92 93 kemiliteran yang bernama Tentara Pelajar. Sekalipun hanya bermodalkan keterampilan baris-berbaris, latihan dasar kemiliteran, serta latihan perang- perangan dengan menggunakan senapan kayu, namun hal ini secara tidak langsung menyebabkan para pelajar memiliki disiplin tinggi sehingga menimbulkan rasa percaya diri pada akhirnya itu semua akan digunakan sebagai modal melawan Belanda.