ATTRACTING and BANNING ANKARI: Musical and Climate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipio De Patacamaya (Agosto 2002 - Enero 2003) 52

Municipio de Patacamaya (Agosto 2002 - enero 2003) Diario de Ángela Copaja En agosto Donde Ángela conoce, antes que nada, el esplendor y derro- che de las fiestas en Patacamaya, y luego se instala para comenzar a trabajar JUEVES 8. Hoy fue mi primer día, estaba histérica, anoche casi no pude dormir y esta mañana tuve que madrugar para tomar la flota y estar en la Alcaldía a las 8:30 a.m. El horario normal es a las 8:00 de la mañana, pero el intenso frío que se viene registrando obligó a instaurar un horario de invierno (que se acaba esta semana). Vine con mi mamá, tomamos la flota a Oruro de las 6:30, llegamos a Patacamaya casi a las ocho y media, y como ya era tarde, tuvimos que tomar un taxi (no sabía que habían por aquí) para llegar a la Al- caldía, pues queda lejos de la carretera. Después de dejarme en mi "trabajo" se fue a buscarme un cuarto, donde se supone me iba a quedar esa noche, pues 51 traje conmigo algunas cosas; me quedaré hoy (jueves) y mañana (viernes) me vuelvo yo solita a La Paz. Ya en la oficina tuve que esperar a que llegara el Profesor Celso (Director de la Dirección Técnica y de Planificación) para que me presentara al Alcalde. Me Revista número 13 • Diciembre 2003 condujo hasta la oficina y me presentó al Profesor Gregorio, el Oficial Mayor, un señor bastante serio que me dio hartísimo miedo pues me trató de una forma muy tosca. Él me presentó al Alcalde, que me dio la bienvenida al Mu- nicipio de Patacamaya muy amablemente. -

Aymara UNIDAD DE COORDINACIÓN DE ASUNTOS INDÍGENAS DEL MINISTERIO DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL Y FAMILIA

Diccionario de la lengua Aymara UNIDAD DE COORDINACIÓN DE ASUNTOS INDÍGENAS DEL MINISTERIO DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL Y FAMILIA Ana Millanao Contreras ASESORA ESPECIAL PARA ASUNTOS INDÍGENAS Francisco Ule Rebolledo COORDINADOR UNIDAD ASUNTOS INDÍGENAS Natalie Castro López Lucy Barriga Cortés COORDINACIÓN GENERAL Andrés García Flores TRADUCCIÓN Rodrigo Olavarría Lavín INVESTIGACIÓN Y EDICIÓN GENERAL Carolina Zañartu Salas Juan Américo Pastene de la Jara Lilian Ferrada Sepúlveda INVESTIGACIÓN, DISEÑO Y DIAGRAMACIÓN Especial agradecimiento a la Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena por su colaboración en la referencia de traductores y revisión. Diccionario de la lengua Aymara Tras varios de meses de trabajo, junto al equipo de la Unidad de Coordinación de Asuntos Indígenas del Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, hemos finalizado el desarrollo de una herramienta, que consideramos de gran importancia para promover las lenguas de los pueblos indígenas de Chile, ya que como Gobierno estamos poniendo especial énfasis en fortalecer y concientizar a la población respecto a su revitalización. Cada uno de los diccionarios —elaborados en lengua aymara, quechua, mapuche y rapa nui— contempla una primera parte con antecedentes de estos pueblos, información sobre la cultura y la cosmovisión, además de datos para comprender aspectos lingüísticos. La segunda parte consta de palabras y su respectiva traducción, divididas por unidades para facilitar el aprendizaje, mediante la asociación. También fueron incluidas frases de uso cotidiano para acercar más la lengua a quienes se interesen en aprender. Invitamos a revitalizar las lenguas indígenas, como parte del merecido reconocimiento a los pueblos indígenas del país. Por otro lado, reafirmamos el compromiso de seguir desarrollando espacios de documentación de las lenguas para mantener vivos estos verdaderos tesoros, que son parte de nuestra identidad. -

Paleoambiente Y Arqueología Del Río Guaquira-Tiwanaku (Bolivia)»: Un Estudio Multidisciplinario De Las Interacciones Entre Las Sociedades Antiguas Y El Medioambiente

Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines 47 (2) | 2018 Varia La misión franco-boliviana « Paleoambiente y Arqueología del r í o Guaquira-Tiwanaku (Bolivia) » : un estudio multidisciplinario de las interacciones entre las sociedades antiguas y el medioambiente La mission franco-bolivienne « Paléoenvironnement et archéologie du río Guaquira-Tiwanaku (Bolivie) » : une étude interdisciplinaire des interactions entre les sociétés anciennes et l’environnement The Franco-Bolivian Mission “Palaeoenvironment and Archaeology of the Guaquira –Tiwanaku River, (Bolivia)”: A multidisciplinary study of the interactions between Ancient Societies and the Environment Marc-Antoine Vella, Sofía Sejas, Karen Lucero Mamani, Luis Alejandro Rodríguez, Ramiro Bello Gómez, Claudia Rivera Casanovas, José Menacho Céspedes, Jaime Argollo, Stéphane Guédron, Élodie Brisset, Gregory Bièvre, Christelle Sanchez, Julien Thiesson, Roger Guérin, Katerina Escobar, Teresa Ortuño y Paz Núñez-Regueiro Edición electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/9777 DOI: 10.4000/bifea.9777 ISSN: 2076-5827 Editor Institut Français d'Études Andines Edición impresa Fecha de publicación: 1 agosto 2018 Paginación: 169-193 ISSN: 0303-7495 2 Referencia electrónica Marc-Antoine Vella, Sofía Sejas, Karen Lucero Mamani, Luis Alejandro Rodríguez, Ramiro Bello Gómez, Claudia Rivera Casanovas, José Menacho Céspedes, Jaime Argollo, Stéphane Guédron, Élodie Brisset, Gregory Bièvre, Christelle Sanchez, Julien Thiesson, Roger Guérin, Katerina Escobar, Teresa Ortuño y Paz Núñez-Regueiro, « La misión franco-boliviana «Paleoambiente y Arqueología del río Guaquira- Tiwanaku (Bolivia)»: un estudio multidisciplinario de las interacciones entre las sociedades antiguas y el medioambiente », Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines [En línea], 47 (2) | 2018, Publicado el 08 agosto 2018, consultado el 04 noviembre 2020. -

Informe Estadístico Del Municipio De El Alto

INFORME ESTADÍSTICO DEL MUNICIPIO DE EL ALTO 2020 ÍNDICE 1. Antecedentes .................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Situación demográfica ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Situación económica ....................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Comercio ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Industria Manufacturera ............................................................................................................... 5 3.3 Acceso a Financiamiento ............................................................................................................... 6 3.4 Ingresos Municipales por Transferencias ...................................................................................... 7 3.5 Empleo ........................................................................................................................................... 8 4. Bibliografía ....................................................................................................................................... 8 ANEXOS ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Índice de Gráficos Gráfico 1: Población -

Colección De Libros TEXTOS POÉTICOS EN VARIOS IDIOMAS Y OTROS CANTOS

Ambassadeur de la Paix 2006 GENEVE CAPITALE MONDIALE de la PAIX. Membre de la Société Mondiale des Poètes - Sociedad Mundial de Poetas (W.P.S.)Grèce 2006. Embajador de Poetas del Mundo en Bolivia 2005. Francisco Azuela, nació en la Ciudad de León, Guanajuato, México, el 8 de marzo de 1948. Es sobrino nieto de Mariano Azuela, primer novelista de la Revolución Mexicana. Estudió en las Universidades de Guanajuato, Iberoamericana, UNAM y Panamericana de la Ciudad de México, y en las Complutense de Madrid y Laval de Québec. Es miembro de la Sociedad General de Escritores de México y Miembro de la International Writers Guild. Fue diplomático en las Embajadas de México en Costa Rica y Honduras (1973-1983) y fue condecorado por el Gobierno hondureño con la Orden del Libertador de Centroamérica FRANCISCO MORAZAN, en el grado de Oficial. Fue candidato de la Academia Hondureña de la Lengua al Premio Internacional de Literatura CENVANTES de España en 1981. Es autor de EL MALDICIONERO (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, 3ª.ed., 1981), EL TREN DE FUEGO (Instituto de la Cultura del Estado de Guanajuato, 1993), LA PAROLE ARDENTE, edición bilingüe (John Donne & Cie., France, 1993), SON LAS CIEN DE LA TARDE (Instituto de la Cultura del Estado de Guanajuato, 1996), ÁNGEL DEL MAR DE MIS SUEÑOS (Centro Cultural Internacional El Cóndor de los Andes-Águila Azteca, A.C., 2000). Además, su obra se ha publicado en Interactions (Department of German-University College, London), Rimbaud Revue (Semestriel International de Création Littéraire, France et la Communauté Européenne des poétes), en la Revista Neruda Internacional y en revistas y antologías de Canadá, Centroamérica, Sudamérica, España, Francia, México, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Austria, Italia, Chile, Bolivia, Brasil e Irán. -

Infected Areas As at 11 May 1995 Zones Infectées Au 11 Mai 1995

WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL RECORD, Ho. It, 12 MAY 1995 • RELEVÉ ÉPIDÉMIOLOGIQUE HEBDOMADAIRE, N‘ H , 12 MAI 1995 M adagascar (4 May 1995).1 The number of influenza M adagascar (4 mai 1995).1 Le nombre d’isolements de virus A(H3N2) virus isolates increased during February and grippaux A(H3N2) s’est accru en février et en mars. Un accrois March. At that time there was a noticeable increase in sement marqué des syndromes grippaux a alors été observé parmi influenza-like illness among the general population in la population générale à Antananarivo. Des virus grippaux Antananarivo. Influenza A(H3N2) viruses continued to be A(H3N2) ont continué à être isolés en avril, de même que quel isolated in April along with a few of H1N1 subtype. ques virus appartenant au sous-type H1N1. Norway (3 May 1995).2 The notifications of influenza-like Norvège (3 mai 1995).2 Les notifications de syndrome grippal ont illness reached a peak in the last week of March and had atteint un pic la dernière semaine de mars et sont retombées à 89 declined to 89 per 100 000 population in the week ending pour 100 000 habitants au cours de la semaine qui s’est achevée le 23 April. At that time, 7 counties, mainly in the south-east 23 avril. Sept comtés, principalement dans le sud-est et l’ouest du and the west, reported incidence rates above 100 per pays, signalaient alors des taux d ’incidence dépassant 100 pour 100 000 and in the following week, 4 counties reported 100 000, et la semaine suivante 4 comtés ont déclaré des taux au- rates above 100. -

Perfil De Tesis

1 UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS FACULTAD DE ARQUITECTURA URBANISMO, DISEÑO Y ARTES CARRERA DE ARQUITECTURA “CRITERIOS DE SELECCION DE LUGAR PARA LA CONSTRUCCION DEL CENTRO RITUAL EN KHONKHO WANKANE; PERIODO FORMATIVO TARDIO” Tesis para obtener el grado de licenciatura POR: GUILLERMO RODRIGO CASTILLLO OLMOS TUTOR: ARQ. JAVIER ESCALANTE M. LA PAZ – BOLIVIA 2012 UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS FACULTAD DE ARQUITECTURA URBANISMO, DISEÑO Y ARTES CARRERA DE ARQUITECTURA Tesis de grado: “CRITERIOS DE SELECCION DE LUGAR PARA LA CONSTRUCCION DEL CENTRO RITUAL EN KHONKHO WANKANE; PERIODO FORMATIVO TARDIO” Presentada por: Univ. Guillermo Rodrigo Castillo Olmos Para optar el grado académico de Licenciado en Arquitectura Nota numeral:………………85……………………………. Nota literal:……………Ochenta y cinco…………………... Ha sido: Aprobado con distinción y mención especial en la línea de investigación de promoción de patrimonio con identidad…………………… Director de la carrera de Arquitectura: Ing. Richard Fernández Tutor: M. Sc. Arq. Javier Escalante Moscoso Tribunal: Ph. D. Arq. Max Arnsdorff Hidalgo Tribunal: M. Sc. Arq. Luis Arellano López Tribunal: M. Sc. Arq. Zazanda Salcedo Gutiérrez 2 A mi madre, Jeanette: Quien me ensenó a sentir con mi piel desnuda la desnuda piel de la naturaleza. 3 TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1 INTRODUCION …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….Pag. 1 1.1 Motivaciones para elección del tema…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Pag. 2 1.2 Objetivos del trabajo………………………………………………………………………………………………………………....………………………. .Pag. 3 1.2.1 -

Indigenous Cosmogony and Andean Architecture in El Alto, Bolivia Franck Poupeau

Indigenous Cosmogony and Andean Architecture in El Alto, Bolivia Franck Poupeau To cite this version: Franck Poupeau. Indigenous Cosmogony and Andean Architecture in El Alto, Bolivia. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Wiley, 2020. hal-03099079 HAL Id: hal-03099079 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03099079 Submitted on 6 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Publisher : John Wiley & Sons, Ltd Location : Chichester, UK DOI : 10.1111/(ISSN)1468-2427 ISSN (print) : 0309-1317 ISSN (electronic) : 1468-2427 ID (product) : IJUR Title (main) : International Journal of Urban and Regional Research Title (short) : Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. Copyright (thirdParty) : 葱 2020 Urban Research Publications Limited Numbering (journalVolume) : 9999 Numbering (journalIssue) : 9999 DOI : 10.1111/1468-2427.12852 ID (unit) : IJUR12852 ID (society) : NA Count (pageTotal) : 12 Title (articleCategory) : Interventions Essay Title (tocHeading1) : Interventions Essay Copyright (thirdParty) : 葱 2020 Urban Research Publications Limited Event -

Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes

Nymsuque: Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes Beatriz Goubert Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Beatriz Goubert All rights reserved ABSTRACT Nymsuque: Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes Beatriz Goubert Muiscas figure prominently in Colombian national historical accounts as a worthy and valuable indigenous culture, comparable to the Incas and Aztecs, but without their architectural grandeur. The magnificent goldsmith’s art locates them on a transnational level as part of the legend of El Dorado. Today, though the population is small, Muiscas are committed to cultural revitalization. The 19th century project of constructing the Colombian nation split the official Muisca history in two. A radical division was established between the illustrious indigenous past exemplified through Muisca culture as an advanced, but extinct civilization, and the assimilation politics established for the indigenous survivors, who were considered degraded subjects to be incorporated into the national project as regular citizens (mestizos). More than a century later, and supported in the 1991’s multicultural Colombian Constitution, the nation-state recognized the existence of five Muisca cabildos (indigenous governments) in the Bogotá Plateau, two in the capital city and three in nearby towns. As part of their legal battle for achieving recognition and maintaining it, these Muisca communities started a process of cultural revitalization focused on language, musical traditions, and healing practices. Today’s Muiscas incorporate references from the colonial archive, archeological collections, and scholars’ interpretations of these sources into their contemporary cultural practices. -

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of Hist

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ABSTRACT Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Elizabeth Shesko 2012 Abstract This dissertation examines the trajectory of military conscription in Bolivia from Liberals’ imposition of this obligation after coming to power in 1899 to the eve of revolution in 1952. Conscription is an ideal fulcrum for understanding the changing balance between state and society because it was central to their relationship during this period. The lens of military service thus alters our understandings of methods of rule, practices of authority, and ideas about citizenship in and belonging to the Bolivian nation. In eliminating the possibility of purchasing replacements and exemptions for tribute-paying Indians, Liberals brought into the barracks both literate men who were formal citizens and the non-citizens who made up the vast majority of the population. -

Social Resistance in El Alto - Bolivia

SOCIAL RESISTANCE IN EL ALTO - BOLIVIA AGUAS DEL ILLIMANI, A CONCESSION TARGETING THE POOR1 by Julián Pérez On 24 July 1997, a contract for the concession of potable water and sewer services was signed between Aguas del Illimani (AISA) and the Bolivian government, through the agency responsible for water (Superintedencia de Servicios Básicos, SISAB), to expand potable water and sanitary sewer services in El Alto and La Paz. Seven years after the company began providing services, and after six months of negotiation and exhausting all possibilities for resolving the conflict, the Federation of Neighbourhood Boards (Federación de Juntas Vecinales, FEJUVE) of the city of El Alto2 called an indefinite strike on 10 January 2005, demanding that the concession contract be rescinded. On 12 January 2005, the Bolivian government issued a supreme decree beginning “actions for the termination of the concession contract with AISA,” a subsidiary of the transnational Suez corporation. The AISA concession process was not transparent, and it ran counter to Bolivian regulations and the country’s legal framework. Stakeholders interested in the issue were excluded from the bidding process and from strategic decision making, which was exclusively centralised in the Bolivian government. During the bidding process, it was said that the privatisation would attract private capital to expand services.3 When the contract was signed, however, many of the terms of the bidding were changed to conform to those of AISA’s offer. A few years after the privatisation, the government, international cooperation agencies and the private sector gave the La Paz – El Alto concession high marks for what they called its pro-poor approach. -

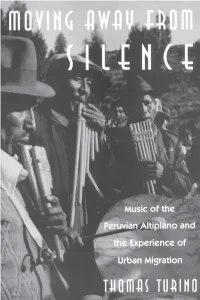

Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experiment of Urban Migration / Thomas Turino

MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl EDITORIAL BOARD Margaret J. Kartomi Hiromi Lorraine Sakata Anthony Seeger Kay Kaufman Shelemay Bonnie c. Wade Thomas Turino MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THOMAS TURlNo is associate professor of music at the University of Ulinois, Urbana. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1993 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1993 Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-81699-0 ISBN (paper): 0-226-81700-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Turino, Thomas. Moving away from silence: music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the experiment of urban migration / Thomas Turino. p. cm. - (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology) Discography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Folk music-Peru-Conirna (District)-History and criticism. 2. Folk music-Peru-Lirna-History and criticism. 3. Rural-urban migration-Peru. I. Title. II. Series. ML3575.P4T87 1993 761.62'688508536 dc20 92-26935 CIP MN @) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. For Elisabeth CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: From Conima to Lima