Indigenous Cosmogony and Andean Architecture in El Alto, Bolivia Franck Poupeau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipio De Patacamaya (Agosto 2002 - Enero 2003) 52

Municipio de Patacamaya (Agosto 2002 - enero 2003) Diario de Ángela Copaja En agosto Donde Ángela conoce, antes que nada, el esplendor y derro- che de las fiestas en Patacamaya, y luego se instala para comenzar a trabajar JUEVES 8. Hoy fue mi primer día, estaba histérica, anoche casi no pude dormir y esta mañana tuve que madrugar para tomar la flota y estar en la Alcaldía a las 8:30 a.m. El horario normal es a las 8:00 de la mañana, pero el intenso frío que se viene registrando obligó a instaurar un horario de invierno (que se acaba esta semana). Vine con mi mamá, tomamos la flota a Oruro de las 6:30, llegamos a Patacamaya casi a las ocho y media, y como ya era tarde, tuvimos que tomar un taxi (no sabía que habían por aquí) para llegar a la Al- caldía, pues queda lejos de la carretera. Después de dejarme en mi "trabajo" se fue a buscarme un cuarto, donde se supone me iba a quedar esa noche, pues 51 traje conmigo algunas cosas; me quedaré hoy (jueves) y mañana (viernes) me vuelvo yo solita a La Paz. Ya en la oficina tuve que esperar a que llegara el Profesor Celso (Director de la Dirección Técnica y de Planificación) para que me presentara al Alcalde. Me Revista número 13 • Diciembre 2003 condujo hasta la oficina y me presentó al Profesor Gregorio, el Oficial Mayor, un señor bastante serio que me dio hartísimo miedo pues me trató de una forma muy tosca. Él me presentó al Alcalde, que me dio la bienvenida al Mu- nicipio de Patacamaya muy amablemente. -

Informe Estadístico Del Municipio De El Alto

INFORME ESTADÍSTICO DEL MUNICIPIO DE EL ALTO 2020 ÍNDICE 1. Antecedentes .................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Situación demográfica ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Situación económica ....................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Comercio ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Industria Manufacturera ............................................................................................................... 5 3.3 Acceso a Financiamiento ............................................................................................................... 6 3.4 Ingresos Municipales por Transferencias ...................................................................................... 7 3.5 Empleo ........................................................................................................................................... 8 4. Bibliografía ....................................................................................................................................... 8 ANEXOS ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Índice de Gráficos Gráfico 1: Población -

Infected Areas As at 11 May 1995 Zones Infectées Au 11 Mai 1995

WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL RECORD, Ho. It, 12 MAY 1995 • RELEVÉ ÉPIDÉMIOLOGIQUE HEBDOMADAIRE, N‘ H , 12 MAI 1995 M adagascar (4 May 1995).1 The number of influenza M adagascar (4 mai 1995).1 Le nombre d’isolements de virus A(H3N2) virus isolates increased during February and grippaux A(H3N2) s’est accru en février et en mars. Un accrois March. At that time there was a noticeable increase in sement marqué des syndromes grippaux a alors été observé parmi influenza-like illness among the general population in la population générale à Antananarivo. Des virus grippaux Antananarivo. Influenza A(H3N2) viruses continued to be A(H3N2) ont continué à être isolés en avril, de même que quel isolated in April along with a few of H1N1 subtype. ques virus appartenant au sous-type H1N1. Norway (3 May 1995).2 The notifications of influenza-like Norvège (3 mai 1995).2 Les notifications de syndrome grippal ont illness reached a peak in the last week of March and had atteint un pic la dernière semaine de mars et sont retombées à 89 declined to 89 per 100 000 population in the week ending pour 100 000 habitants au cours de la semaine qui s’est achevée le 23 April. At that time, 7 counties, mainly in the south-east 23 avril. Sept comtés, principalement dans le sud-est et l’ouest du and the west, reported incidence rates above 100 per pays, signalaient alors des taux d ’incidence dépassant 100 pour 100 000 and in the following week, 4 counties reported 100 000, et la semaine suivante 4 comtés ont déclaré des taux au- rates above 100. -

ATTRACTING and BANNING ANKARI: Musical and Climate

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lund University Publications - Student Papers ATTRACTING AND BANNING ANKARI: Musical and Climate Change in the Kallawaya Region in Northern Bolivia Degree of Master of Science (Two Years) in Human Ecology: Culture, Power and Sustainability 30 ECTS CPS: International Master’s Programme in Human Ecology Human Ecology Division Department of Human Geography Faculty of Social Sciences Lund University by Sebastian Hachmeyer Department: Department of Human Geography Human Ecology Division Address: Geocentrum Sölvegatan 10 223 62 Lund Telephone: 046-222 17 59 Supervisor: Dr. Anders Burman Dr. Bernardo Rozo Lopez Department of Human Geography Department of Anthropology Human Ecology Division UMSA Lund University, Sweden La Paz, Bolivia Title and Subtitle: Attracting and Banning Ankari: Musical and Climate Change in the Kallawaya Region in Northern Bolivia Author: Sebastian Hachmeyer Examination: Master’s thesis (two year) Term: Spring Term 2015 Abstract: In the Kallawaya region in the Northern Bolivian Andes musical practices are closely related to the social, natural and spiritual environment: This is evident during the process of constructing and tuning instruments, but also during activities in the agrarian cycle, collective ritual and healing practices, as means of communication with the ancestors and, based on a Kallawaya perspective, during the critical involvement in influencing local weather events. In order to understand the complexity of climate change in the Kallawaya region beyond Western ontological principles the latter is of great importance. The Northern Bolivian Kallawaya refer to changes in climate as a complex of changes in local human-human and human- environmental relations based on a rupture of a certain morality and reciprocal relationship in an animate world in which music plays an important role. -

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of Hist

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ABSTRACT Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Elizabeth Shesko 2012 Abstract This dissertation examines the trajectory of military conscription in Bolivia from Liberals’ imposition of this obligation after coming to power in 1899 to the eve of revolution in 1952. Conscription is an ideal fulcrum for understanding the changing balance between state and society because it was central to their relationship during this period. The lens of military service thus alters our understandings of methods of rule, practices of authority, and ideas about citizenship in and belonging to the Bolivian nation. In eliminating the possibility of purchasing replacements and exemptions for tribute-paying Indians, Liberals brought into the barracks both literate men who were formal citizens and the non-citizens who made up the vast majority of the population. -

Social Resistance in El Alto - Bolivia

SOCIAL RESISTANCE IN EL ALTO - BOLIVIA AGUAS DEL ILLIMANI, A CONCESSION TARGETING THE POOR1 by Julián Pérez On 24 July 1997, a contract for the concession of potable water and sewer services was signed between Aguas del Illimani (AISA) and the Bolivian government, through the agency responsible for water (Superintedencia de Servicios Básicos, SISAB), to expand potable water and sanitary sewer services in El Alto and La Paz. Seven years after the company began providing services, and after six months of negotiation and exhausting all possibilities for resolving the conflict, the Federation of Neighbourhood Boards (Federación de Juntas Vecinales, FEJUVE) of the city of El Alto2 called an indefinite strike on 10 January 2005, demanding that the concession contract be rescinded. On 12 January 2005, the Bolivian government issued a supreme decree beginning “actions for the termination of the concession contract with AISA,” a subsidiary of the transnational Suez corporation. The AISA concession process was not transparent, and it ran counter to Bolivian regulations and the country’s legal framework. Stakeholders interested in the issue were excluded from the bidding process and from strategic decision making, which was exclusively centralised in the Bolivian government. During the bidding process, it was said that the privatisation would attract private capital to expand services.3 When the contract was signed, however, many of the terms of the bidding were changed to conform to those of AISA’s offer. A few years after the privatisation, the government, international cooperation agencies and the private sector gave the La Paz – El Alto concession high marks for what they called its pro-poor approach. -

4.4 Charana Achiri Santiago De Llallagua Is. Taquiri General Gonzales 3.0 3.1 2.9

N ULLA ULLA TAYPI CUNUMA CAMSAYA CALAYA KAPNA OPINUAYA CURVA LAGUNILLA GRAL. J.J. PEREZ CHULLINA STA. ROSA DE CAATA CHARI GRAL. RAMON CARIJANA GONZALES 2.0 CAMATA AMARETEGENERAL GONZALES MAPIRI VILLA ROSARIO DE WILACALA PUSILLANI CONSATA MARIAPU INICUA BAJO MOCOMOCO AUCAPATA SARAMPIUNI TUILUNI AYATA HUMANATA PAJONAL CHUMA VILAQUE ITALAQUE SUAPI DE ALTO BENI SAN JUAN DE CANCANI LIQUISANI COLLABAMBA GUANAY COTAPAMPA TEOPONTE PUERTO ACOSTA CHINAÑA 6 SANTA ROSA DE AGOSTO ANANEA CARGUARANI PAUCARES CHAJLAYA BELEN SANTA ANA DEL TAJANI PTO. ESCOMA 130 PANIAGUA ALTO BENI PARAJACHI ANBANA TACACOMA YANI QUIABAYA TIPUANI COLLASUYO PALOS BLANCOS V. PUNI SANTA ROSA DE CHALLANA SAN MIGUEL CALLAPATA CALAMA EDUARDO AVAROA DE YARICOA TIMUSI OBISPO BOSQUE SOCOCONI VILLA ELEVACION PTO. CARABUCO CARRASCO LA RESERVA CHUCHULAYA ANKOMA SAPUCUNI ALTO ILLIMANI ROSARIO 112 SORATA CARRASCO ENTRE RIOS PTO. COMBAYA 115 CHAGUAYA ILABAYA ALCOCHE SAN PABLO SOREJAYA SANTA FE CHIÑAJA CARANAVI VILLA MACA MACA CHEJE MILLIPAYA ANCORAIMES SANTA ANA DE CARANAVI PAMPA UYUNENSE CAJIATA FRANZ TAMAYO PTO.RICO SOTALAYA TAYPIPLAYA WARISATA CHOJÑA COTAPATA SAN JUAN DE CHALLANA INCAHUARA DE CKULLO CUCHU ACHACACHI SAN JOSE V. SAN JUAN DE EL CHORO SANTIAGO AJLLATA V. ASUNCION DE CHACHACOMANI ZAMPAYA CORPAPUTO KALAQUE DE HUATA GRANDE CHARIA JANCKO AMAYA CHUA HUARINA MURURATA LA ASUNTA COPACABANA COCANI KERANI TITO YUPANKI CHUA SONCACHI CALATA VILASAYA HUATAJATA LOKHA DE S. M. SAN PABLO PEÑAS VILLA ASUNCION HUAYABAL DE T. COPANCARA TURGQUIA ZONGO KARHUISA COROICO CALISAYA CHAMACA V. AMACIRI2.9 PACOLLO SANTIAGO DE IS. TAQUIRI YANAMAYU SURIQUI HUANCANE OJJE PTO. ARAPATA COLOPAMPA GRANDE PEREZ VILLA BARRIENTOS LA CALZADA CASCACHI HUAYNA POTOSI LAS BATALLAS MERCEDES CORIPATA V. -

Lista De Centros De Educación Alternativa – La Paz

LISTA DE CENTROS DE EDUCACIÓN ALTERNATIVA – LA PAZ N NIVEL - APELLIDOS Y TELEFONOS DISTRITO CEAS Localidad Dirección CARGO º SERVICIOS NOMBRES CEL MAMANI ACHACA AVENIDA MANCO 1 ACHACACHI EPA - ESA ACHACACHI MERCEDES 73087375 DIRECTOR CHI KAPAC ALVARO COMUNIDAD EXPERIMEN SAN ACHACA EPA-ESA- TICONA HUANCA 2 TAL FRANCISCO CMD. AVICHACA DIRECTOR CHI ETA VIDAL AVICHACA DE AVICHACA - ZONA BAJA PLAZA ANDRES DE SANTA CRUZ - ACHACA SOBRE LA PLAZA DIRECTOR 3 HUARINA EPA - ESA HUARINA CHI PRINCIPAL ENCARGADO FRENTE A LA IGLESIA ACHACA JANCKO JANKHO 4 EPA - ESA JANCKO AMAYA CALLE M. TOMAS 70542707 DIRECTORA CHI AMAYA AMAYA ACHACA SANTIAGO SANTIAGO DE SANTIAGO DE 5 EPA - ESA DIRECTOR CHI DE HUATA C HUATA HUATA ACHOCALLA - TOLA ACHOCA SUMA DIRECTOR 6 EPA - ESA CIUDAD ACHOCALLA SALVATIERRA 69996813 LLA QAMAÑA ENCARGADO ACHOCALLA PATRICIA LUCIA ANCORAI EPA-ESA- 7 LITORAL ANCORAIMES CALLE S/N QUISPE MAXIMO 73741569 DIRECTOR MES ETA INMACULAD HUANCA A LITORAL SIN 8 APOLO EPA - ESA APOLO CHOQUETARQUI 65557929 DIRECTOR CONCEPCIO NUMERO RUBEN N DE APOLO AUCAPA AUCAPATA EPA-ESA- APAZA LAURA 9 AUCAPATA AUCAPATA 72024119 DIRECTOR TA ISKANWAYA ETA FRANCISCO 26 DE MAYO 1 BATALLA QUISPE POCOTA DIRECTORA CHACHACO EPA - ESA BATALLAS CALLE LITORAL 73093955 0 S MARINAS ENCARGADA MANI COMUNIDAD VILLA SAN ESPIRITU BATALLA EPA-ESA- JUAN DE 11 SANTO ZONA KORUYO DIRECTOR S ETA CHACHACOM (CONVENIO) ANI - ZONA KORUYO 1 CALACO DIRECTORA CALACOTO EPA - ESA CALACOTO CALACOTO 2 TO ENCARGADA CALACO DIRECTOR 13 ULLOMA B EPA - ESA ULLOMA ULLOMA TO ENCARGADO 1 CARANA CALLE LITORAL CARANAVI EPA - ESA CARANAVI CRUZ E. SANTOS DIRECTOR 4 VI S/N HNO. -

2017 Jul Bolivia

WEFTA SPONSORED TRIP TO BOLIVIA UMA – WATER – AGUA EL ALTIPLANO, BOLIVIA TRIP REPORT Related to Site Visit made by WEFTA VOLUNTEERS to El Altiplano, Bolivia July 7 – July 17, 2017 The Altiplano (Spanish for “high plain”), Collao Andean Plateau or Bolivian Plateau, in west- central South America, is the area where the Andes are the widest. It is the most extensive area of high plateau on Earth outside of Tibet. The bulk of the Altiplano lies in Bolivia, but the remaining parts lie in Peru, Chile and Argentina. La Paz and El Alto with over one-million inhabitants are the largest combined cities in Latin America inhabited by indigenous Americans and the highest major metropolis in the world. July 7 - 17, 2017 Page 1 Ramón 505-660-2186 [email protected] WEFTA SPONSORED TRIP TO BOLIVIA WEFTA SPONSORED PROJECTS El Altiplano, Bolivia Table of Contents Site Visit Overview………………………………………………………………...3 Bolivia Site Visit Agenda…………………………………………………………..5 Justin, Liz and Brook Login Report………………………………………………..6 Jason Gehrig Report………………………………………………………………11 Richard & Dolores Mulliken Report……………………………………………...16 Sara Mason Report………………………………………………………………..19 José Ortiz Report………………………………………………………………….23 July 7 - 17, 2017 Page 2 Ramón 505-660-2186 [email protected] WEFTA SPONSORED TRIP TO BOLIVIA Kamisaraki (Aymara Greeting) On July 7, 2017 a small group of nine WEFTA volunteers traveled from the arid southwest United States to El Altiplano of Bolivia. The nine volunteers comprised of Jason Gehrig, Water Engineer, Justin Logan, Wastewater Engineer, José Ortiz and Sara Mason, Engineers in Training (EIT)s, Richard Mulliken, Surveyor, Ramón Lucero, Water Resource Project Managers and Dolores Mulliken, and Liz and Brook Login collectively from New Mexico, Utah and Texas traveled to El Alto/La Paz Bolivia with the following four goals. -

Drought Risk in the Bolivian Altiplano Associated with El Niño Southern Oscillation Using Satellite Imagery Data

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2018-403 Manuscript under review for journal Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 27 March 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Drought risk in the Bolivian Altiplano associated with El Niño Southern Oscillation using satellite imagery data Claudia Canedo-Rosso1,2, Stefan Hochrainer-Stigler3, Georg Pflug3,4, Bruno Condori5, and Ronny Berndtsson1,6 5 1Division of Water Resources Engineering, Lund University, P.O. Box 118, SE-22100 Lund, Sweden 2 Instituto de Hidráulica e Hidrología, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, Cotacota 30, La Paz, Bolivia 3 International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Schlossplatz 1, A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria 4 Institute of Statistics and Operations Research, Faculty of Economics, University of Vienna, Oskar-Morgenstern- Platz 1, 1090 Wien, Austria 10 5 Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agropecuaria y Forestal (INIAF), Batallón Colorados 24, La Paz, Bolivia. 6 Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Lund University, P.O. Box 201, SE-22100 Lund, Sweden. Correspondence to: Claudia Canedo-Rosso ([email protected] and [email protected]) Abstract. Drought is a major natural hazard in the Bolivian Altiplano that causes large losses to farmers, especially during positive ENSO phases. However, empirical data for drought risk estimation purposes are scarce 15 and spatially uneven distributed. Due to these limitations, similar to many other regions in the world, we tested the performance of satellite imagery data for providing precipitation and temperature data. The results show that droughts can be better predicted using a combination of satellite imagery and ground-based available data. -

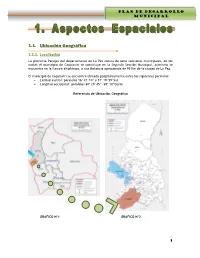

1.1. Ubicación Geográfica

PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL G.M. CAQUIAVIRI 1.1. Ubicación Geográfica 1.1.1. Localización La provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz consta de ocho secciones municipales, de los cuales el municipio de Caquiaviri se constituye en la Segunda Sección Municipal, asimismo se encuentra en la llanura altiplánica, a una distancia aproximada de 95 Km de la ciudad de La Paz. El municipio de Caquiaviri se encuentra ubicado geográficamente entre los siguientes paralelos: Latitud austral: paralelos 16º 47´10” y 17º 19´59”Sur Longitud occidental: paralelos 68º 29´45”- 69º 10”Oeste Referencia de Ubicación Geográfica GRAFICO Nº1 GRAFICO Nº2 1 PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL G.M. CAQUIAVIRI Ubicación del Municipio Caquiaviri en la Provincia Pacajes GRAFICO Nº3 1.1.2. Límites Territoriales El municipio de Caquiaviri tiene la siguiente delimitación: Límite Norte; Municipios de Jesús de Machaca y San Andrés de Machaca de la provincia Ingavi y el Municipio Nazacara de Pacajes que es la Séptima Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Sur; Municipios Coro Coro, Calacoto y Charaña que son Primera, Tercera y Quinta Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Este; Municipio Comanche que es Cuarta Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Oeste; Municipio de Santiago de Machaca de la provincia José Manuel Pando del departamento de La Paz. 1.1.3. Extensión La Provincia Pacajes posee una extensión total de 10.584 km², de la cual la Segunda Sección Municipal Caquiaviri representa el 14 % del total de la provincia, lo que equivale a una superficie de 1.478 Km². -

Signs of the Time: Kallawaya Medical Expertise and Social Reproduction in 21St Century Bolivia by Mollie Callahan a Dissertation

Signs of the Time: Kallawaya Medical Expertise and Social Reproduction in 21st Century Bolivia by Mollie Callahan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Judith T. Irvine, Chair Professor Bruce Mannheim Associate Professor Barbra A. Meek Associate Professor Javier C. Sanjines Dedicada a la comunidad de Curva (en su totalidad) y mis primeros amores, Jorge y Luka. ii Acknowledgements There are many people without whom this dissertation would have never been conceived, let alone completed. I am indebted first and foremost to my mother, Lynda Lange, for bringing me into this world and imparting her passion for reading, politics, and people well before she managed to complete her bachelor’s degree and then masters late into my own graduate studies. She has for as long as I can remember wished for me to achieve all that I could imagine and more, despite the limitations she faced in pursuing her own professional aspirations early in her adult life. Out of self-less love, and perhaps the hope of also living vicariously through my own adventures, she has persistently encouraged me to follow my heart even when it has delivered me into harms way and far from her protective embrace. I am eternally grateful for the freedom she has given me to pursue my dreams far from home and without judgment. Her encouragement and excitement about my own process of scholarly discovery have sustained me throughout the research and writing of this dissertation.