Is Alejandro Leiva Wenger a Case of in Between Literature?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parra-A-La-Vista-Web-2018.Pdf

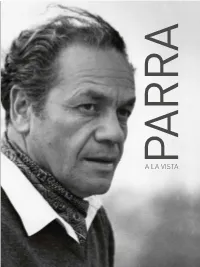

1 LIBRO PARRA.indb 1 7/24/14 1:24 PM 2 LIBRO PARRA.indb 2 7/24/14 1:24 PM A LA VISTAPARRA 3 LIBRO PARRA.indb 3 7/24/14 1:24 PM 4 LIBRO PARRA.indb 4 7/24/14 1:24 PM A LA VISTAPARRA 5 LIBRO PARRA.indb 5 7/24/14 1:24 PM PARRA A LA VISTA © Nicanor Parra © Cristóbal Ugarte © AIFOS Ediciones Dirección y Edición General Sofía Le Foulon Investigación Iconográfica Sofía Le Foulon Cristóbal Ugarte Asesoría en Investigación María Teresa Cárdenas Textos María Teresa Cárdenas Diseño Cecilia Stein Diseño Portada Cristóbal Ugarte Producción Gráfica Alex Herrera Corrección de Textos Cristóbal Joannon Primera edición: agosto de 2014 ISBN 978-956-9515-00-2 Esta edición se realizó gracias al aporte de Minera Doña Inés de Collahuasi, a través de la Ley de Donaciones Culturales, y el patrocinio de la Corporación del Patrimonio Cultural de Chile Edición limitada. Prohibida su venta Todos los derechos reservados Impreso en Chile por Ograma Impresores Ley de Donaciones Culturales 6 LIBRO PARRA.indb 6 7/24/14 1:24 PM ÍNDICE Presentación 9 Prólogo 11 Capítulo I | 1914 - 1942 NICANOR SEGUNDO PARRA SANDOVAL 12 Capítulo II | 1943 - 1953 EL INDIVIDUO 32 Capítulo III | 1954 - 1969 EL ANTIPOETA 60 Capítulo IV | 1970 - 1980 EL ENERGÚMENO 134 Capítulo V | 1981 - 1993 EL ECOLOGISTA 184 Capítulo VI | 1994 - 2014 EL ANACORETA 222 7 LIBRO PARRA.indb 7 7/24/14 1:24 PM 8 capitulos1y2_ALTA.indd 8 7/28/14 6:15 PM PRESENTACIÓN odo comenzó con una maleta llena de fotografías de Nicanor Parra que su nieto Cristóbal Ugarte, el Tololo, encontró al ordenar la biblioteca de su abuelo en su casa de La Reina, después del terremoto Tde febrero de 2010. -

Nobel De Literatura 2011: Tomas Tranströmer. Uno De Sus

9 de octubre de 2011 Entevista / Sergio Badilla Castillo / Senderos de la palabra Nobel de Literatura 2011: Tomas Tranströmer. Uno de sus traductores describe al poeta como un ser extraordinario, interesado en el intercambio de vivencias a través de la letra Auxilio Alcantar A pesar de su grandeza como poeta, Tomas Tranströmer es un hombre muy sencillo, con gran sensibilidad para tratar a las personas y para extraer poesía de lo cotidiano, asegura el traductor Sergio Badilla Castillo. Traductor de Visión nocturna (1986), Senderos (1994) e innumerables poemas de Tranströmer, el académico y escritor chileno se considera admirador de su obra y un discípulo literario del Nobel 2011. En entrevista, Badilla Castillo narra cómo nació décadas atrás su relación con el sueco. ¿Cuál ha sido su reacción al saber que Tomas Tranströmer ha recibido hoy el Premio Nobel de Literatura? De una profunda emoción, es como un rayo de luz, porque soy un seguidor de la poesía de Tomas Tranströmer. Y soy feliz porque había sido olvidado por una cuestión de lógica sueca. Durante los 80 y 90, Tranströmer tenía dos grandes amigos en la Academia, que fueron sus compañeros de generación. Ambos eran amigos íntimos y se pensaba que podían influir para que él ganara el Nobel. Un premio que pudieron haberle dado mucho antes porque realmente lo merecía, gracias a esa extraordinaria obra. Sin embargo, ambos lo dijeron de manera explicita y pública: nunca iban a otorgárselo porque eran amigos. No olvide que la Academia estipula que no debe haber ningún tipo de intimidad entre los miembros de la Academia y los posibles premiados. -

La Casa Teillier “El Origen Del Lar”

La Casa Teillier “El Origen del Lar” Volumen N° 1, Edición N°1 24 de JUNIO DE 2020 LAR: Etimológicamente la palabra lar pasado histórico con la tradi- es sinónimo de hogar. Frecuen- ción cultural . temente se usa en plural, de modo que una expresión como Desde el lar hace hincapié en la búsqueda de los valores del Contenido: “vuelvo a mis lares” equivale decir, “vuelvo a mi hogar, vuel- paisaje, del pueblo, de la aldea vo a mi patria, vuelvo al lugar y de la provincia, confluyendo LAR 1 que pertenezco o al que me así imágenes nostálgicas de la infancia perdida y de la natura- vio nacer”. ALGO DE 1 leza primigenia del mito. HISTORIA El significado de la palabra Lar, según el Diccionario de la Real EL CLAN 2 Academia Española (RAE), TEILLIER SAN- significa: “Lugar de origen de DOVAL una persona o casa en la que vive con su familia”. LAS VISITAS 2 (los progresistas) Dicho de otra forma, el lar es la carga psicológica y emocio- LAS VISITAS 2 nal que vincula los espacios de cultura y arte 1 la memoria otorgando impor- tancia a los recuerdos, a los LAS VISITAS 3 lugares habitados y deshabita- cultura y el arte 2 dos, constituyéndose así en recodos de la historia personal, SIEMPRE MI 3 familiar y colectiva. El lar, la CASA casa, es el inicio de la relación MI CASA, MIS 3 metafórica que da cuenta de la VERSOS actividad poética de Jorge Tei- LICEO H.C 4 llier basada en la memoria JORGE TEILLIER testimonial que relaciona un PLAZA JORGE 4 TEILLIER ESCULTURA 4 JORGE TEILLIER CAMBIO DE AN- 5 DÉN JORGE TEILLIER ALGO DE HISTORIA 5 EN LAUTARO Casa ubicada en calle Saavedra da nunca se utilizó como tal. -

Fångenskap Och Flykt: Om Frihetstemat I Svensk Barndomsskildring

Fångenskap och ykt Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. FÅNGENSKAP OCH FLYKT Om frihetstemat i svensk barndomsskildring, reseskildring och science ction decennierna kring Svante Landgraf ISAK, Tema Kultur och samhälle (Tema Q) Filososka fakulteten Linköpings universitet, SE- Linköping, Sverige Linköping Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. Vid lososka fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskning- en är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbild- ningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Gemensamt ger de ut serien Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Denna avhandling kommer från Tema Q, Kultur och samhälle, vid Institutionen för studier av samhällsutveckling och kultur. : Institutionen för studier av samhällsutveckling och kultur Linköpings universitet Linköping © Svante Landgraf Minion Pro och Myriad Pro av författaren LiU-Tryck, Linköping, : Linköping Studies in Arts and Science, No. - ---- INNEHÅLL Förord ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ......................................................................................................................................................... Sy e och analytiska frågor • Perspektiv och tillvägagångssätt • Tre genrer och ett texturval • Forskningslägen • Disposition -

Link: Visitas: Favorabilidad

Fecha: 04/08/2020 Visitas: 2.681 Favorabilidad: No Definida Fuente: Culto.LaTercera Título: Nicanor Parra, el poeta que no usó seudónimo Link: https://www.latercera.com/culto/2019/09/05/nicanor-parra-el-poeta-que-no-uso-seudonimo/ El 23 de enero de 2018, Nicanor Parra, el hombre que alguna vez escribió "la poesía terminó conmigo", murió a los 103 años, exactamente ochenta después de declararle "la guerra a la metáfora". Estas son algunas lecturas sobre su obra, la que, a la manera de Pessoa, es también su propia biografía. -La ciencia aborda el mundo de lo real. La filosofía, además, el de lo posible. El epígrafe abre una tesis universitaria que no parece tesis, sino que una novela encubierta sobre la vida y obra de Descartes. Lleva por título René Descartes: datos biográficos, estudios de su obra, juicios críticos y fue expuesta al gran público, a finales de 2012, en la Biblioteca de Humanidades de la Universidad de Chile. El texto corresponde a la tesis con que Nicanor Parra optó al grado de profesor de Matemáticas y Física cuando tenía 26 años. Un ensayo literario que por momentos parece incómodo en esa habitación de lo académico y que por eso escapa, se desborda para dar paso a un lenguaje lleno de desparpajo y soltura. Catorce años antes de Poemas y antipoemas (Nascimento, 1954), ese libro rojo, esa tesis universitaria, deja sentir que ahí, en poco más de cien páginas, late algo que vendrá después, como sugiere el escritor Diego Zúñiga en revista Qué Pasa : "La cadencia particular de la antipoesía, la fluidez del lenguaje, el habla de la tribu". -

Indice General

Justo Alarcón Reyes José Apablaza Guerra Miriam Guzmán Morales Revistas Culturales Chilenas del Siglo XX INDICE GENERAL Sin título-1 1 7/3/07 10:40:51 Revistas Culturales Chilenas del Siglo XX ÍNDICE GENERAL Obra financiada con el aporte del Fondo Nacional de Fomento del Libro y la Lectura, del Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes Revistas Culturales Chilenas del Siglo XX Índice General © Justo Alarcón, José Apablaza, Miriam Guzmán N° Inscripción 159.863 ISBN 978-956-310-514-8 Primera edición: diciembre 2006 800 ejemplares Diagramación e impresión Andros Impresores www.androsimpresores.cl Justo Alarcón Reyes José Apablaza Guerra Miriam Guzmán Morales Revistas Culturales Chilenas del Siglo XX INDICE GENERAL GOBIERNO DE CHILE MINISTERIO DE SALUD INSTITUTO DE SALUD PUBLICA DE CHILE SUMARIO Presentación 9 Introducción 11 I. Nómina de Revistas Indizadas 15 1. Alerce; 2. Amargo; 3. Áncora; 4. Andes; 5. Árbol de Letras; 6. Arte y Cultura; 7. Artes y Letras; 8. Arúspice; 9. Aurora; 10. Calicanto; 11. Carta de Poesía; 12. Clímax; 13. Cormorán; 14. Extremo Sur; 15. Gong; 16. Grupos; 17. Juventud; 18. La Honda; 19. Litoral; 20. Mandrágora; 21. Mástil; 22. Millantún; 23. Orfeo; 24. Pomaire; 25. Puelche; 26. Quilodrán; 27. Revista del Pacífico; 28. Revista Literaria de la Sociedad de Escritores de Chile; 29. SECH; 30. Studium; 31. Tierra; 32. Total; 33. Travesía. II. Índice General de Materias 27 III. Índice Onomástico 221 PRESENTACIÓN He aquí una nueva investigación de Justo Alarcón y su equipo. Su trabajo constante ha consistido en construir un espacio amistoso para los investigadores. No se trata sólo de la relación personal, humana, que ha establecido con ellos, sino, además, un segundo gesto de generosidad al llevar a cabo una labor importante, aunque fatigosa, la de ordenar en índices pormenorizados un gran catálogo de las revistas culturales de Chile. -

LENA CRONQVIST Født 1938

LENA CRONQVIST Født 1938 Education The National College of Arts, Crafts and Design Stockholm, Sweden, 1958-59 The Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm, Sweden, 1959-64 Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts Solo Exhibitions 2006 Nancy Margolis Gallery, New York, NY 2005 Saltarvet, Studio Lena Cronqvist, New York, NY Bror Hjorts Hus, Uppsala, Sweden 2004 Tikanojas Konsthem, Vasa, Finland Alingsås Konsthall, Alingsås, Sweden Arnstedt & Kullgren, Östra Karup, Sweden 2003 SAK, Stockholm, Sweden Galleri Dobloug, Oslo, Norway Malmö Konstmuseum, Malmö, Sweden Skövde Konsthall, Skövde, Sweden 2002 Vita ark, Gallery Lars Bohman, Stockholm Vida Museum, Halitorp 2001 Rackstadmuseet, Arvika, Sweden 2000 Galleri Tricia Collins Contemporary Art, New York Lokstallet, Strömstad, Sweden Panncentralen, Kristinehamns Konstmuseum 1999 I flickans tid, Gallery Lars Bohman, Stockholm Tricia Collins Contemporary Art, New York 1998 KunstnerfØrbundet, Oslo Retrospective, Konstmuseet, Helsingborg, Sweden 1997 Gallery Nordanstad, New York Gallery SØlvberget, Stavanger, Norge 1996 Aknaton Gallery, Center of Arts, Zamalek, Cairo, Egypt Gallery Dobloug, Oslo Gallery Kamras, Borgholm 1995 Flickor i New York, Gallery Lars Bohman, Stockholm 1994 Retrospective, Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm Retrospective, Göteborgs Konsthall 1993 Gallery Dobloug, Oslo Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum,Tromsö, Norge, Norway 1992 Retrospective, Värmlands Museum, Karlstad Jönköpings läns museum, Sweden 1991 Små flickor, Gallery Lars Bohman, Stockholm Samtidsmuseet, Oslo, Norway 1990 Gallery -

History 3711: the Past Is a Predator: Southern Cone Military Juntas of the Late Twentieth Century University of Connecticut Department of History Fall 2013

History 3711: The Past is a Predator: Southern Cone Military Juntas of the late twentieth century University of Connecticut Department of History Fall 2013 Kim Worthington - [email protected] Office Number: Wood Hall 330 Office hours: Tuesdays, 2-4pm or by appointment Lecture: Tuesdays and Thursdays 12:30-1:45pm, Family Studies Building Room 202 Please note that, for the purposes of obtaining feedback from colleagues, I include notes on my thinking in developing the syllabus in orange font. These do not form part of the syllabus that students are given. This is the lecturer’s copy. This course aims to equip students with a working knowledge of the rise, workings, and ramifications of the military junta governments of the southern cone states of Latin America (Argentina and Chile in particular) from the 1970s on. More importantly the course is designed to challenge students to approach these circumstances from multiple historical perspectives and engage the tools of critical thinking, both in broad terms and with the specificity that situations require. We will use a range of source materials, including documentaries, government reports and memoranda, newspaper articles, historical monographs, personal narratives, fictional representations of historical events (in film), and others. Our focus will be on approaching all sources as historians, with a critical awareness of the current purposes that records and narratives serve, as well as the pasts from which they have emerged. While some scholarly articles are included as readings, the course aims to stimulate students to investigate primary sources themselves, and to shape their own understandings through a range of sources through which the story of the past can be unearthed. -

Soviética Rusa

El jardín de los poetas. Revista de teoría y crítica de poesía latinoamericana Año VI, n° 10, primer semestre de 2020. ISSN: 2469-2131. Artículos. Soares da Silva-Pinheiro Convergências da poesia russa moderna na América Latina dos anos 1960: Nicanor Parra, Boris Schnaiderman, Haroldo e Augusto de Campos Gabriela Soares da Silva Universidade de São Paulo (USP) Departamento de Letras Orientais Brasil [email protected] om Tiago Guilherme Pinheiro Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem Brasil [email protected] Resumo: O artigo se propõe a recuperar o contexto histórico e os procedimentos de produção de duas importantes antologias latino-americanas de poesia russa: a Poesía soviética rusa (1965), depois republicada como Poesía rusa contemporánea (1972), do chileno Nicanor Parra, e a Poesia russa moderna (1ª edição, 1968), de Boris Schnaiderman, Augusto de Campos e Haroldo de Campos. Com esta análise, busca-se demonstrar como a antologia constitui uma forma poético-literária singular. Palavras-chave: Antologias; Poesia russo-soviética; Tradução; Nicanor Parra; Concretismo brasileiro; Boris Schnaiderman. Convergences of Modern Russian Poetry in 1960's Latin America: Nicanor Parra, Boris Schnaiderman, Haroldo and Augusto de Campos Abstract: The article recovers the historical context and the production procedures of two important Latin American anthologies of Russian poetry: Poesía soviética rusa (1965), later renamed Poesía rusa contemporánea (1972), by Nicanor Parra, and Poesia russa moderna (first edition, 1967), by Boris Schnaiderman, Haroldo and Augusto de Campos. Through this analysis, the anthology genre shows its potency as a singular poetic-literary form. 154 El jardín de los poetas. -

CARMEN BERENGUER Barro (Inédito) Se Veía Luminoso Una Chatarra MINI ENTREVISTA Cruzar El Desierto Tenía La Por Max G

CARMEN BERENGUER MINI ENTREVISTA Barro (Inédito) Por Max G. Sáez Se veía luminoso una chatarra cruzar el desierto tenía la Pero es sin duda mi propia experiencia con la palabra y con el duda con el agua fría bajado espacio del habla mi parpadeo con la lengua, es desde donde el río esa no era más que un me sitúo en otra esfera, sin propiedad, donde he pensado que el acto de escribir mancha fierro viejo como un sol para ¿Qué es la escritura, la poesía y cómo ves tú escribir poesía? la iglesia de ella de guarda en la iglesia salieron los El concepto de escritura tiene que ver con que hay una noción de retratos verás los santos de otredad y la pregunta acerca de la diferencia entre la literatura y la escritura: la literatura pertenece al espacio del significado fundado las divisiones y una virgen por la cultura greco-latina. Al contrario, la escritura no excluye a nortina diciendo esta posición ninguna cultura, en especial porque remite a una palabra que incluye a la dirigente viendo con la otredad, y es interminable porque es apertura, confesión, marca, lágrimas en los ojos viendo cuerpo, espacio. Precisamente es producto de mi práctica con la escritura y lectura de la filosofía a partir de Derrida, pero también los ojos como tristes llenos de desde mis preguntas por el canon y también de lecturas de Roland sangre inyectados en sangre Barthes cuando dijo que la literatura se estudia. la virgen del norte la virgen de los poseídos por virgen de Carmen, ¿qué es lo que deben hacer los poetas en la los bailes le dicen de la tirana actualidad? ¿Cómo ves que eso se expresa, se escribe, se mueve, en los poetas actuales? de julio el verano del alto lluvioso bajaba a los bailes Bueno, lo que ocurre que son aquellos discursos que no se alcanzaron viendo en medio del silencio a leer en la modernidad, por ejemplo, los feminismos, el queer, después que había bajado poscolonialismo, el punk, el rock, expresiones de la diversidad cultural que se expresan en este siglo y que no fueron incluidos en el canon el barro como una procesión dominante. -

«Por Lo Menos Mi Recuerdo Será El De Un Hombre Digno»*

NOTAS SOLEDAD BIANCHI «Por lo menos mi recuerdo será el de un hombre digno»* odavía me extraña recorrer, en Santiago, una calle llamada Salva- dor Allende. Como por casualidad, sin conocerla, vine a dar a esta, Tno muy lejos de Macul, que no pertenece a Ñuñoa porque si usted mira el Plano de Santiago, encontrará varias, todas en comunas popula- res. Y mientras la Salvador Allende atraviesa Puente Alto, las Presidente Salvador Allende se extienden en Huechuraba, Lo Espejo, Cerrillos y San Joaquín, pareciendo enhebrar un mapa de la pobreza urbana. Como sintiéndome en falta, me detengo en los letreros que la anun- cian, sospechando un castigo por violar la prohibición de nominar al proscrito, pero, claro, nada sucede porque ya terminó la dictadura, y aunque sin ganas, la actual democracia ha autorizado estos bautizos, en pp. 92-94 sectores pobres y populosos. Y sigo mi trayecto, mientras otras gentes pasan, raudas, por esta calle Presidente Salvador Allende, sin enterarse /2008 casi de su nombre, o considerándolo, tal vez, tan lejano o desconocido como otros apelativos de avenidas, pasajes o cruces citadinos. Y así como, para algunos, Allende no resuene, hoy, más que como el apellido de un antiguo veterano, teñido por sangre, y no solo por la propia, quizá como un hombre culpable de muchas penas y dolores, para otros será el dirigente honesto que se negó a claudicar porque creía en la justicia de su quehacer y, posiblemente, nadie se pondrá de acuer- No. octubre-diciembre 253 do, y será difícil que hoy, a veinticinco años de su muerte, haya -

Esfera, Pez Y Hexagrama: El LOGO De Pablo Neruda

NERUDIANA – nº 3 – 2007 [ 1 ] nerudiana Fundación Pablo Neruda Santiago Chile nº 3 Agosto 2007 Director Hernán Loyola Esfera, Pez y Hexagrama: el LOGO de Pablo Neruda ENRIQUE ROBERTSON / HERNÁN LOYOLA Bielefeld, Alemania / Sássari, Italia escriben e intentará en este ensayo: 1) aclarar el ori- Fernando Benítez gen y significado del logo nerudiano; 2) Dominique Casimiro S identificar al artista que lo diseñó. Tarea pen- Edmundo Olivares diente que, según veremos, Osvaldo Rodríguez Sara Reinoso Canelo Musso inició hace unos veinte años. Enrique Robertson Según el diccionario, logo o logotipo es un Gonzalo Rojas símbolo formado por letras y/o por imágenes. El Waldo Rojas logo de Neruda está formado por las seis letras del Mario Valdovinos sigue en p. 2 21319 NERUDIANA.P65 1 19/8/08, 14:00 [ 2 ] NERUDIANA – nº 3 – 2007 nombre y por la horizontal imagen de un riosos artefactos, cuya representación grá- Sumario pez que mira hacia la izquierda, rodeado fica, hoy como ayer, confiere su fuerza sim- por unos anillos que esquemáticamente re- bólica a grabados, ex libris, logotipos, etc. presentan una antigua esfera armilar. En el centro de la esfera armilar del Esfera, Pez y Hexagrama: 1 el LOGO de Pablo Neruda La esfera armilar, perfeccionada hace logo nerudiano, en lugar de la Tierra –y ENRIQUE ROBERTSON / HERNÁN LOYOLA medio milenio por el sabio danés Tycho sin que sepamos por qué– está el Pez. Brahe, es un fáustico instrumento compues- Una antigua ilustración del Fausto de En el centenario de Miguel Prieto 8 to de anillas –círculos armillares, los llama Goethe nos informa que el protagonista tie- (España 1907—México 1956) Neruda– que representan los círculos de la ne en su laboratorio una esfera armilar.