Day Nine Bibliography Chile As a Focus of Political Debates. Many

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies the University of Texas at Austin 2008–2009 Issue No

TERESA LOZANO LONG INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN StUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN 2008–2009 ISSUE NO. 4 2008–2009 TERESA LOZANO LONG INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES I THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR................................................................................................................................ 3 THE CHAllENGES OF GlOBAliZAtiON: AN INTERVIEW WITH ERNESTO ZEDILLO...................................................................................................................5 LATIN AMERICAN DEVELOPMENTS IN The “AGE OF MIGRATIon”.......................................................................8 VIJAI PATCHINEELAM: A WORK IN PROCESS...........................................................................................................12 REINVIGORAtiNG OlD TIES: CHINA AND LAtiN AMERICA IN THE TWENTY-FiRST CENTURY...........................................................................16 GRADUATE EDUCAtiON AND THE PRACtiCE OF HUMAN RiGHTS....................................................................20 HUMAN RiGHTS IN BRAZil FROM AN UNDERGRADUATE PERSPECtiVE..........................................................22 ECONOMICS AND DEMOCRACY: AN INTERVIEW WitH MiGUEL AlEMÁN VELASCO.................................................................................................24 ARGENtiNA TO TEXAS: THE VALUE OF EXCHANGE..............................................................................................27 OlMEC LANDMARK FOR LlilAS.................................................................................................................................30 -

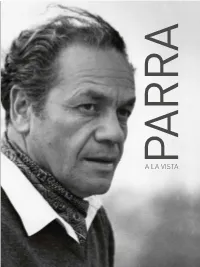

Parra-A-La-Vista-Web-2018.Pdf

1 LIBRO PARRA.indb 1 7/24/14 1:24 PM 2 LIBRO PARRA.indb 2 7/24/14 1:24 PM A LA VISTAPARRA 3 LIBRO PARRA.indb 3 7/24/14 1:24 PM 4 LIBRO PARRA.indb 4 7/24/14 1:24 PM A LA VISTAPARRA 5 LIBRO PARRA.indb 5 7/24/14 1:24 PM PARRA A LA VISTA © Nicanor Parra © Cristóbal Ugarte © AIFOS Ediciones Dirección y Edición General Sofía Le Foulon Investigación Iconográfica Sofía Le Foulon Cristóbal Ugarte Asesoría en Investigación María Teresa Cárdenas Textos María Teresa Cárdenas Diseño Cecilia Stein Diseño Portada Cristóbal Ugarte Producción Gráfica Alex Herrera Corrección de Textos Cristóbal Joannon Primera edición: agosto de 2014 ISBN 978-956-9515-00-2 Esta edición se realizó gracias al aporte de Minera Doña Inés de Collahuasi, a través de la Ley de Donaciones Culturales, y el patrocinio de la Corporación del Patrimonio Cultural de Chile Edición limitada. Prohibida su venta Todos los derechos reservados Impreso en Chile por Ograma Impresores Ley de Donaciones Culturales 6 LIBRO PARRA.indb 6 7/24/14 1:24 PM ÍNDICE Presentación 9 Prólogo 11 Capítulo I | 1914 - 1942 NICANOR SEGUNDO PARRA SANDOVAL 12 Capítulo II | 1943 - 1953 EL INDIVIDUO 32 Capítulo III | 1954 - 1969 EL ANTIPOETA 60 Capítulo IV | 1970 - 1980 EL ENERGÚMENO 134 Capítulo V | 1981 - 1993 EL ECOLOGISTA 184 Capítulo VI | 1994 - 2014 EL ANACORETA 222 7 LIBRO PARRA.indb 7 7/24/14 1:24 PM 8 capitulos1y2_ALTA.indd 8 7/28/14 6:15 PM PRESENTACIÓN odo comenzó con una maleta llena de fotografías de Nicanor Parra que su nieto Cristóbal Ugarte, el Tololo, encontró al ordenar la biblioteca de su abuelo en su casa de La Reina, después del terremoto Tde febrero de 2010. -

Kessler, Judd.Docx

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project JUDD KESSLER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 19, 2010 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Newark, New Jersey March 1938 Grandparents’ Generation – Eastern Europe, Latvia Parents Occupations Vibrant Neighborhood Education Oberlin College, Ohio President of Student Council Levels of Anti-Semitism Harvard Law Favorite Professor Henry Hart, Jr. Law Office Internship Army Reserve Sojourn to Europe Return to Law Office Joined Agency for International Development October 1966 East Asia Bureau Attorney Advisor Philippine cement plant negotiations Latin America Bureau Negotiating loan agreements Chile, Regional Legal Advisor Spring 1969 Spanish Language Training Also covered Argentina, Bolivia Allende Wins Election Loan Management Difference White House and Embassy/AID Approach View of Christian Democrats Nationalization Changes Kessler’s Focus Role of OPIC Insurance Ambassador Korry’s Cables on Allende 1 Negative Embassy Reporting Ambassador Korry Tries to Negotiate Nationalizations Ambassador Nathanial Davis Arrives at Post October 1971 Chilean Economic Problems, Political Tension Appointed Acting AID Director April 1973 Coup Overthrows Allende Sept 1973 Post-Coup search for Charles Horman Post-Coup Economic Policies Human Rights Circumstances Ambassador David Popper Arrives at Post Feb 1974 Stories of Allende’s Death Senator Kennedy’s Interest in A Nutritionist Supporting the Chicago Boys Undersecretary -

CIA), Oct 1997-Jan 1999

Description of document: FOIA Request Log for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Oct 1997-Jan 1999 Requested date: 2012 Released date: 2012 Posted date: 08-October-2018 Source of document: FOIA Request Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1998 Case Log Creation Date Case Number Case Subject 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02319 FOIA REQUEST VIETNAM CONFLICT ERA 1961 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02320 FOIA REQUEST PROFESSOR ZELLIG S. HARRIS FOIA REQUEST FOR MEETING MINUTES OF THE PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COORDINATING COMMITTEE 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02321 (PDCC) 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02322 FOIA REQUEST RE OSS REPORTS AND PAPERS BETWEEN ALLEN DULLES AND MARY BANCROFT 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02323 FOIA REQUEST CIA FOIA GUIDES AND INDEX TO CIA INFORMATION SYSTEMS 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02324 FOIA REQUEST FOR INFO ON SELF 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02325 FOIA REQUEST ON RAOUL WALLENBERG 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02326 FOIA REQUEST RE RAYMOND L. -

S17-Macmillan-St.-Martins-Griffin.Pdf

ST. MARTIN'S GRIFFIN APRIL 2017 Killing Jesus A History Bill O'Reilly The third book in Bill O’Reilly’s multimillion bestselling Killing series, Killing Jesus delivers the story of Jesus’s crucifixion as it’s never been told before. Sixteen million readers have been thrilled by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard’s Killing series, page-turning works of nonfiction that have changed the way we read history. Now the anchor of The O’Reilly Factor, the highest-rated cable news show in the country, details the events leading up to the murder of the most HISTORY St. Martin's Griffin | 4/4/2017 influential man who ever lived: Jesus of Nazareth. Nearly two thousand years 9781250142207 | $15.99 / $22.99 Can. after this beloved and controversial young revolutionary was brutally killed by Trade Paperback | 304 pages Roman soldiers, more than 2.2 billion people attempt to follow his teachings 8.3 in H | 5.5 in W and believe he is God. In this fascinating and fact-based account of Jesus’s life Subrights: UK Rights: Henry Holt and times, Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, Caesar Augustus, Herod the Great, Pontius Translation rights: Henry Holt Pilate, and John the Baptist are among the many legendary historical figures Other Available Formats: who rise up off the page. Killing Jesus not only takes readers inside this most Hardcover ISBN: 9780805098549 volatile epoch, it also recounts the seismic political and historical events that Ebook ISBN: 9780805098556 made Jesus’s death inevitable—and changed the world forever. Audio ISBN: 9781427233325 PRA ISE Praise for The Killing Series: “All the suspense and drama of a popular thriller.” —The Christian Science Monitor “If Grisham wrote a novel about April 1865...it might well read like Killing Lincoln.” —Peter J. -

Nobel De Literatura 2011: Tomas Tranströmer. Uno De Sus

9 de octubre de 2011 Entevista / Sergio Badilla Castillo / Senderos de la palabra Nobel de Literatura 2011: Tomas Tranströmer. Uno de sus traductores describe al poeta como un ser extraordinario, interesado en el intercambio de vivencias a través de la letra Auxilio Alcantar A pesar de su grandeza como poeta, Tomas Tranströmer es un hombre muy sencillo, con gran sensibilidad para tratar a las personas y para extraer poesía de lo cotidiano, asegura el traductor Sergio Badilla Castillo. Traductor de Visión nocturna (1986), Senderos (1994) e innumerables poemas de Tranströmer, el académico y escritor chileno se considera admirador de su obra y un discípulo literario del Nobel 2011. En entrevista, Badilla Castillo narra cómo nació décadas atrás su relación con el sueco. ¿Cuál ha sido su reacción al saber que Tomas Tranströmer ha recibido hoy el Premio Nobel de Literatura? De una profunda emoción, es como un rayo de luz, porque soy un seguidor de la poesía de Tomas Tranströmer. Y soy feliz porque había sido olvidado por una cuestión de lógica sueca. Durante los 80 y 90, Tranströmer tenía dos grandes amigos en la Academia, que fueron sus compañeros de generación. Ambos eran amigos íntimos y se pensaba que podían influir para que él ganara el Nobel. Un premio que pudieron haberle dado mucho antes porque realmente lo merecía, gracias a esa extraordinaria obra. Sin embargo, ambos lo dijeron de manera explicita y pública: nunca iban a otorgárselo porque eran amigos. No olvide que la Academia estipula que no debe haber ningún tipo de intimidad entre los miembros de la Academia y los posibles premiados. -

La Casa Teillier “El Origen Del Lar”

La Casa Teillier “El Origen del Lar” Volumen N° 1, Edición N°1 24 de JUNIO DE 2020 LAR: Etimológicamente la palabra lar pasado histórico con la tradi- es sinónimo de hogar. Frecuen- ción cultural . temente se usa en plural, de modo que una expresión como Desde el lar hace hincapié en la búsqueda de los valores del Contenido: “vuelvo a mis lares” equivale decir, “vuelvo a mi hogar, vuel- paisaje, del pueblo, de la aldea vo a mi patria, vuelvo al lugar y de la provincia, confluyendo LAR 1 que pertenezco o al que me así imágenes nostálgicas de la infancia perdida y de la natura- vio nacer”. ALGO DE 1 leza primigenia del mito. HISTORIA El significado de la palabra Lar, según el Diccionario de la Real EL CLAN 2 Academia Española (RAE), TEILLIER SAN- significa: “Lugar de origen de DOVAL una persona o casa en la que vive con su familia”. LAS VISITAS 2 (los progresistas) Dicho de otra forma, el lar es la carga psicológica y emocio- LAS VISITAS 2 nal que vincula los espacios de cultura y arte 1 la memoria otorgando impor- tancia a los recuerdos, a los LAS VISITAS 3 lugares habitados y deshabita- cultura y el arte 2 dos, constituyéndose así en recodos de la historia personal, SIEMPRE MI 3 familiar y colectiva. El lar, la CASA casa, es el inicio de la relación MI CASA, MIS 3 metafórica que da cuenta de la VERSOS actividad poética de Jorge Tei- LICEO H.C 4 llier basada en la memoria JORGE TEILLIER testimonial que relaciona un PLAZA JORGE 4 TEILLIER ESCULTURA 4 JORGE TEILLIER CAMBIO DE AN- 5 DÉN JORGE TEILLIER ALGO DE HISTORIA 5 EN LAUTARO Casa ubicada en calle Saavedra da nunca se utilizó como tal. -

Fångenskap Och Flykt: Om Frihetstemat I Svensk Barndomsskildring

Fångenskap och ykt Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. FÅNGENSKAP OCH FLYKT Om frihetstemat i svensk barndomsskildring, reseskildring och science ction decennierna kring Svante Landgraf ISAK, Tema Kultur och samhälle (Tema Q) Filososka fakulteten Linköpings universitet, SE- Linköping, Sverige Linköping Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. Vid lososka fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskning- en är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbild- ningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Gemensamt ger de ut serien Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Denna avhandling kommer från Tema Q, Kultur och samhälle, vid Institutionen för studier av samhällsutveckling och kultur. : Institutionen för studier av samhällsutveckling och kultur Linköpings universitet Linköping © Svante Landgraf Minion Pro och Myriad Pro av författaren LiU-Tryck, Linköping, : Linköping Studies in Arts and Science, No. - ---- INNEHÅLL Förord ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ......................................................................................................................................................... Sy e och analytiska frågor • Perspektiv och tillvägagångssätt • Tre genrer och ett texturval • Forskningslägen • Disposition -

Link: Visitas: Favorabilidad

Fecha: 04/08/2020 Visitas: 2.681 Favorabilidad: No Definida Fuente: Culto.LaTercera Título: Nicanor Parra, el poeta que no usó seudónimo Link: https://www.latercera.com/culto/2019/09/05/nicanor-parra-el-poeta-que-no-uso-seudonimo/ El 23 de enero de 2018, Nicanor Parra, el hombre que alguna vez escribió "la poesía terminó conmigo", murió a los 103 años, exactamente ochenta después de declararle "la guerra a la metáfora". Estas son algunas lecturas sobre su obra, la que, a la manera de Pessoa, es también su propia biografía. -La ciencia aborda el mundo de lo real. La filosofía, además, el de lo posible. El epígrafe abre una tesis universitaria que no parece tesis, sino que una novela encubierta sobre la vida y obra de Descartes. Lleva por título René Descartes: datos biográficos, estudios de su obra, juicios críticos y fue expuesta al gran público, a finales de 2012, en la Biblioteca de Humanidades de la Universidad de Chile. El texto corresponde a la tesis con que Nicanor Parra optó al grado de profesor de Matemáticas y Física cuando tenía 26 años. Un ensayo literario que por momentos parece incómodo en esa habitación de lo académico y que por eso escapa, se desborda para dar paso a un lenguaje lleno de desparpajo y soltura. Catorce años antes de Poemas y antipoemas (Nascimento, 1954), ese libro rojo, esa tesis universitaria, deja sentir que ahí, en poco más de cien páginas, late algo que vendrá después, como sugiere el escritor Diego Zúñiga en revista Qué Pasa : "La cadencia particular de la antipoesía, la fluidez del lenguaje, el habla de la tribu". -

Killers of IWW Member Frank Teruggi Sentenced in Chile

Killers of IWW member Frank Teruggi sentenced in Chile In February 2015, two former Chilean military intelligence officers were convicted of the murder of IWW member Teruggi and another American, Charles Horman. Teruggi and Horman were kidnapped, tortured and murdered during the military coup in Chile in 1973. Frank Teruggi, an IWW member from Chicago and a native of Des Plaines, Ill., was kidnapped, tortured and murdered during the military coup in Chile in 1973. On Feb. 4, 2015 two Chilean military intelligence officers were convicted of the murder of Fellow Worker (FW) Teruggi and another American, Charles Horman. Brigadier General Pedro Espinoza was sentenced to seven years in the killings of both men. Rafael González, who worked for Chilean Air Force Intelligence as a “civilian counterintelligence agent,” was sentenced to two years in the Horman murder only. Espinoza is currently serving multiple sentences for other human rights crimes as well. A third indicted man, U.S. Naval Captain Ray Davis, head of the U.S. Military Group at the U.S. Embassy in Santiago at the time of the coup, has since died. Teruggi, 24, and Horman, 31, had gone to Chile to see and experience the new socialist government of President Salvador Allende. FW Terrugi participated in protest marches in Santiago following the unsuccessful June 1973 military attempt referred to as the “Tanquetazo” or “Tancazo.” FBI documents show that the agency monitored him, labeling him a “subversive” due to his anti-Vietnam war activities, and participation in assisting draft evaders. FBI files also list his street address in Santiago. -

Indice General

Justo Alarcón Reyes José Apablaza Guerra Miriam Guzmán Morales Revistas Culturales Chilenas del Siglo XX INDICE GENERAL Sin título-1 1 7/3/07 10:40:51 Revistas Culturales Chilenas del Siglo XX ÍNDICE GENERAL Obra financiada con el aporte del Fondo Nacional de Fomento del Libro y la Lectura, del Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes Revistas Culturales Chilenas del Siglo XX Índice General © Justo Alarcón, José Apablaza, Miriam Guzmán N° Inscripción 159.863 ISBN 978-956-310-514-8 Primera edición: diciembre 2006 800 ejemplares Diagramación e impresión Andros Impresores www.androsimpresores.cl Justo Alarcón Reyes José Apablaza Guerra Miriam Guzmán Morales Revistas Culturales Chilenas del Siglo XX INDICE GENERAL GOBIERNO DE CHILE MINISTERIO DE SALUD INSTITUTO DE SALUD PUBLICA DE CHILE SUMARIO Presentación 9 Introducción 11 I. Nómina de Revistas Indizadas 15 1. Alerce; 2. Amargo; 3. Áncora; 4. Andes; 5. Árbol de Letras; 6. Arte y Cultura; 7. Artes y Letras; 8. Arúspice; 9. Aurora; 10. Calicanto; 11. Carta de Poesía; 12. Clímax; 13. Cormorán; 14. Extremo Sur; 15. Gong; 16. Grupos; 17. Juventud; 18. La Honda; 19. Litoral; 20. Mandrágora; 21. Mástil; 22. Millantún; 23. Orfeo; 24. Pomaire; 25. Puelche; 26. Quilodrán; 27. Revista del Pacífico; 28. Revista Literaria de la Sociedad de Escritores de Chile; 29. SECH; 30. Studium; 31. Tierra; 32. Total; 33. Travesía. II. Índice General de Materias 27 III. Índice Onomástico 221 PRESENTACIÓN He aquí una nueva investigación de Justo Alarcón y su equipo. Su trabajo constante ha consistido en construir un espacio amistoso para los investigadores. No se trata sólo de la relación personal, humana, que ha establecido con ellos, sino, además, un segundo gesto de generosidad al llevar a cabo una labor importante, aunque fatigosa, la de ordenar en índices pormenorizados un gran catálogo de las revistas culturales de Chile. -

US Foreign Policy During the Nixon and Ford Administrations

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 3-2012 US Foreign Policy During the Nixon and Ford Administrations Rachael S. Murdock DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Murdock, Rachael S., "US Foreign Policy During the Nixon and Ford Administrations" (2012). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 115. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/115 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. US FOREIGN POLICY TOWARD CHILE DURING THE NIXON AND FORD ADMINISTRATIONS A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts March 2012 BY Rachael Murdock Department of International Studies College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, IL i DEDICATION To my family, whose encouragement and support were essential to the completion of this project. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A very hearty thanks to my thesis advisor, Dr. Rose Spalding, Professor of Political Science at DePaul University. Her patience, guidance, encouragement, insight as she mentored me through the thesis process were indispensible. Great thanks also to Dr. Patrick Callahan, Professor of Political Science at DePaul. He provided vital insight and guidance in developing Chapter Two of this thesis and offered excellent input on later drafts of both Chapters One and Two.