The Clonal Structure of Quercus Geminata Revealed by Conserved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

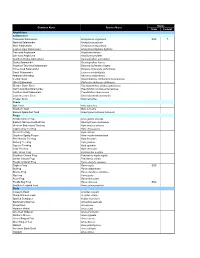

St. Joseph Bay Native Species List

Status Common Name Species Name State Federal Amphibians Salamanders Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum SSC T Marbled Salamander Ambystoma opacum Mole Salamander Ambystoma talpoideum Eastern Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum tigrinum Two-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma means One-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma pholeter Southern Dusky Salamander Desmognathus auriculatus Dusky Salamander Desmognathus fuscus Southern Two-lined Salamander Eurycea bislineata cirrigera Three-lined Salamander Eurycea longicauda guttolineata Dwarf Salamander Eurycea quadridigitata Alabama Waterdog Necturus alabamensis Central Newt Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis Slimy Salamander Plethodon glutinosus glutinosus Slender Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus spheniscus Gulf Coast Mud Salamander Pseudotriton montanus flavissimus Southern Red Salamander Pseudotriton ruber vioscai Eastern Lesser Siren Siren intermedia intermedia Greater Siren Siren lacertina Toads Oak Toad Bufo quercicus Southern Toad Bufo terrestris Eastern Spadefoot Toad Scaphiopus holbrooki holbrooki Frogs Florida Cricket Frog Acris gryllus dorsalis Eastern Narrow-mouthed Frog Gastrophryne carolinensis Western Bird-voiced Treefrog Hyla avivoca avivoca Cope's Gray Treefrog Hyla chrysoscelis Green Treefrog Hyla cinerea Southern Spring Peeper Hyla crucifer bartramiana Pine Woods Treefrog Hyla femoralis Barking Treefrog Hyla gratiosa Squirrel Treefrog Hyla squirella Gray Treefrog Hyla versicolor Little Grass Frog Limnaoedus ocularis Southern Chorus Frog Pseudacris nigrita nigrita Ornate Chorus Frog Pseudacris -

The Effect of Season of Fire on the Recovery of Florida Scrub

2B.7 THE EFFECT OF SEASON OF FIRE ON THE RECOVERY OF FLORIDA SCRUB Tammy E. Foster* and Paul A. Schmalzer Dynamac Corporation, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 1. ABSTRACT∗ scrub, rosemary scrub, and scrubby flatwoods (Myers 1990, Abrahamson and Hartnett 1990). Florida scrub is a xeromorphic shrubland that is Florida scrub is habitat for threatened and maintained by frequent fires. Historically, these fires endangered plants and animals (Christman and Judd occurred during the summer due to lightning ignition. 1990, Stout and Marion 1993, Stout 2001). Today, Florida scrub is often managed by the use of Management of remaining scrub is critical to the survival prescribed burning. Prescribed burning of scrub has of these species. Scrub is a fire-maintained system been implemented on Kennedy Space Center/Merritt (Myers 1990, Menges 1999), and recovery after fire of Island National Wildlife Refuge (KSC/MINWR) since oak scrub and scrubby flatwoods is primarily through 1981, with burns being carried out throughout the year. sprouting and, in some species, clonal spread of the The impacts of the season of burn on recovery are not dominant shrubs (Abrahamson 1984a, 1984b, known. Long-term monitoring of scrub regeneration has Schmalzer and Hinkle 1992a, Menges and Hawkes been conducted since the early-1980’s at KSC/MINWR 1998). Scrub naturally burned during the summer using permanent 15 m line-intercept transects. We months due to lightning ignition. However, landscape obtained data from eight transects that were subjected fragmentation and fire suppression have reduced fire to a winter burn in 1986 and a summer burn in 1997 and size and frequency (Myers 1990, Duncan and compared the recovery of the stand for the first five Schmalzer 2001). -

Northern Yellow Bat Roost Selection and Fidelity in South Carolina

Final Report South Carolina State Wildlife Grant SC T-F16AF00598 South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) May 1, 2016-June 30, 2017 Project Title: Northern Yellow Bat Roost Selection and Fidelity in South Carolina Mary Socci, Palmetto Bluff Conservancy (PBC), Jay Walea, PBC, Timothy White, PBC, Jason Robinson, Biological Systems Consultants, Inc., and Jennifer Kindel, SCDNR Objective 1: Radio-track healthy Northern yellow bats (≤ 10) captured by mist netting appropriate habitat in spring, summer, and fall 2016, ideally with at least 3 radio-tracking events in each season. Record roost switching, and describe roost sites selected. Accomplishments: Introduction: The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the roost site selection and fidelity of northern yellow bats (Lasiurus intermedius, syn. Dasypterus intermedius) by capturing, radio- tagging and tracking individual L. intermedius at Palmetto Bluff, a 15,000 acre, partially-developed tract in Beaufort County, South Carolina (Figures 1 and 2). Other objectives (2 and 3) were to obtain audio recordings of bats foraging in various habitats across the Palmetto Bluff property, including as many L. intermedius as possible and to initiate a public outreach program in order to educate the community on both the project and the environmental needs of bats, many of which are swiftly declining species in United States. Figure 1. Location of Palmetto Bluff 1 Figure 2. The Palmetto Bluff Development Tract The life history of northern yellow bats, a high-priority species in the Southeast, is poorly understood. Studies in coastal Georgia found that all yellow bats that were tracked roosted in Spanish moss in southern live oaks (Quercus virginiana) and sand live oaks (Quercus geminata) (Coleman et al. -

Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources: Forest Trees

Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources . Chittaranjan Kole Editor Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources Forest Trees Editor Prof. Chittaranjan Kole Director of Research Institute of Nutraceutical Research Clemson University 109 Jordan Hall Clemson, SC 29634 [email protected] ISBN 978-3-642-21249-9 e-ISBN 978-3-642-21250-5 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-21250-5 Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922649 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2011 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: deblik, Berlin Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Dedication Dr. Norman Ernest Borlaug,1 the Father of Green Revolution, is well respected for his contribu- tions to science and society. There was or is not and never will be a single person on this Earth whose single-handed service to science could save millions of people from death due to starvation over a period of over four decades like Dr. -

Growth and Recovery of Oak-Saw Palmetto Scrub Through Ten Years After Fire Paul A

Growth and Recovery of Oak-Saw Palmetto Scrub through Ten Years After Fire Paul A. SChmalzer RESEARCH ARTICLE ABSTRACT: Oak-saw palmetto scrub, a shrub community of acid, sandy, well-drained soils in Florida, is maintained by periodic, intense fIre. Understanding the direction and rates of changes in scrub composition and structure after fire is important to management decisions. We followed changes in vegeta.tion along 15Cm linecintercepttransects that were established in 1983. Two stands (8 transects) burned in a prescribed fire in December 1986; the stands had previously burned 11 y (N=4) and 7 y (N=4) before. We sampled transects at 6, 12, 18, and 24 rna and then annually through 10 y after the • 1986 fire. We measured cover by species in two height classes, > 0.5 m and < 0.5 m, and measured height at four points (0, 5, 10, and 15 m) along each transect. Saw palmetto cover equaled preburn values by· one year postburn and changed little after that. Cover of oaks > 0.5 m (Quercus myrtifolia, Q. Growth and geminata, Q. chapmanii) equaled preburn values by 5 y postburn and changed little by 10 Y postburn. Height growth continued, increasing from a mean of 84.0 cm at 5 y to 125.9 cm at 10 y postburn. Bare ground declined to <2% by 3 Y postburn. Plant species richness increased slightly after fire and then Recovery of Oak gradually declined. These vegetation changes alter habitat conditions for threatened and endangered Saw Pal metto Scrub animals and plants. Crecimiento y Recuperaci6n del 'Oak-Saw Palmetto Scrub' Durante Diez Anos through Ten Years Despues del Fuego RESUMEN: EI 'Oak-saw palmetto scrub' es una comunidad de arbustos de suelos :kidos, arenosos y After Fire bien drenados en Florida, mantenidos por fuegos peri6dicos e intensos. -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization. -

Taxonomy and Systematics of Quercus Subgenus Cyclobalanopsis

Figure 4/ Strict consensus tree of 600 MP cladograms from ITS (CI = 0.545; RI = 0.803). Bootstrap proportions using MP are indicated above branches (discussion, p. 55). 48 Taxonomy and Systematics of Quercus Subgenus Cyclobalanopsis Min Deng1, Zhekun Zhou2*, Qiansheng Li3 2. Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, 3. School of Ecology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai Institute of Technology, Kunming, 650223, China. 100 Haiquan Rd., Shanghai, 201418, China 1. Chenshan Plant Sciences Research Center, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chenshan Botanical Garden, 3888 ChenHua Rd., Shanghai, 201602, China. Phone: +86-21- 57 79 93 82; Fax: + 86-21-67657811. [email protected]; ABSTRACT Quercus subgenus Cyclobalanopsis is one of the dominant woody plant groups in E and SE Asia, but comprehensive studies on its systematics and taxonomy are limited. In this study, we compared the leaf epidermal and acorn features of 52 species in subgenus Cyclobalanopsis and 15 species from Quercus subgenus Quercus. We also studied molecular phylogeny using DNA sequences from the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region and the chloroplast psbA–trnH and trnT–trnL regions. Both the leaf epidermal and acorn features indicated ʏve morphologically distinct groups in Cyclobalanopsis: 1) Gilva group (fused stellate trichomes with compound trichome base); 2) Kerrii group (with fasciculate trichomes, and radicles emerging from the basal seed scar; 3) Pachyloma group (papillae on epidermal cells, but glabrous when mature and densely yellowish woolly on the cupule walls); 4) Jenseniana group (lamellae mostly fused to the cupule wall with only the rims free); 5) Glauca group (appressed-lateral-attached trichomes). -

The Vegetative Communities Associated with Mammals of the South

The Vegetative Communities Associated with Mammals of the South Beverly Collins, Philip E. Hyatt, and Margaret K. Trani Introduction This chapter describes the ecoregions and vegetation (www.plants.usda.gov). Mammal species known to occur types associated with mammals of the South. The (or those with a high likelihood of occurrence) in each distribution of mammals in the South reflects historic terrestrial community are listed in Table 2.2. The veg- biogeographicalprocessesaswellasphysiography etation categories are superimposed on the National and vegetation. For example, there are clear differences Hierarchical Framework of Ecological Units (Avers in the mammal fauna of the Blue Ridge Mountains as et al. 1994, Keys et al. 1995) and the ecoregions of the compared to that of the Coastal Plain physiographic United States (Bailey 1995). From interior to coastal area. Within the Coastal Plain there are differences in areas, these ecoregions are the Interior Low Plateau the mammal faunas among mesic pine flatwoods, and Highlands, Cumberland Plateau and Mountains, mixed hardwood forests, and floodplain forests. Blue Ridge and Ridge and Valley, and Coastal Plain Mammalian distributions are often best predicted at and Coastal Fringe. the scale of physiographic province (considering geo- morphology, soils, topography, and micro-climatic The Interior Low Plateau and Highlands differences) and broadly defined vegetation types. Within the broad vegetation categories, adherence to The western mesophytic/oak-hickory forest is broadly specific cover types may be of value in predicting the distributed over the Interior Low Plateau, Coastal presence or absence of a particular mammal; thus, the Plain, and Interior Highlands regions of western basic types of Hamel (1992) and Wilson (1995) are Kentucky, Tennessee, northern Mississippi, Alabama, incorporated within the vegetation descriptions in northern Arkansas, and portions of eastern Oklahoma this book. -

Live Oak Pub 10-23

Tree Dendrology Series WSFNR10-23 Nov. 2010 Live Oak: Historic Ecological Structures by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Live oak (Quercus virginiana) is an ecological and cultural icon of the Southern United States. The species live oak has a diverse set of individual traits across many types of sites, and contains a number of varieties and hybrids. Live oak can be a massive spreading tree along the lower Coastal Plain. Live oak can also be a small, wind-swept tree growing on sand ridges near the ocean. Live oak is much more varied than its steriotype. Live oaks are ecological structures with great canopy and root spread outward from a large diameter, squat stem. The trees are sources of food, protection, and support to a host of other plants and animals. They are life centers and life generators whereever they grow. Live oaks also represent a marker for the history of this nation, and the nations which have come before. Live oaks have served humans and animals as food, fuel, lumber, chemicals, and shade. Today live oak represents both an biological and social heritage. Spiritial For humans, live oaks generate awe, reverence, utility, and a sense of place. There are many live oak treaty trees or assemby trees across the South. Live oak is symbolic of history, survival, struggle, and romance. For example, live oaks were the focus of this nation’s first publicly owned timber reserves for building naval vessels. The largest trees were valuable to sailing ship builders because of their branch shapes and wood strength. -

Florida Scrub Is a Plant Community Easily Recognized

Florida Scrub Including Scrubby Flatwoods and Scrubby High Pine lorida scrub is a plant community easily recognized FNAI Global Rank: G2/G3 by the dominance of evergreen shrubs and frequent FNAI State Rank: S2 Fpatches of bare, white sand. With more than two Federally Listed Species in S. FL: 32 dozen threatened and endangered species dependent upon scrub, the entire community is itself endangered. Recovery State Listed Species in S. FL: 100 of the community and its associated plants and animals will depend upon land acquisition and effective land Florida scrub. Original photograph courtesy of The management. Nature Conservancy. Synonymy Florida scrub in its various phases has been called xeric scrub, sand scrub, big scrub, sand pine scrub, oak scrub, evergreen oak scrub, dune oak scrub, evergreen scrub forest, slash pine scrub, palmetto scrub, rosemary scrub, and rosemary bald. Florida scrubs may be classified as coastal or interior. Scrubs are often named by the dominant plant species, as in rosemary scrub, sand pine scrub, palmetto scrub, or oak scrub. Some authors have confused closed-canopy forests of sand pine trees with scrub. Scrubs that are very recent in origin, usually a result of mans activities, are called pioneer scrubs. Communities intermediate between scrub and pine flatwoods have been called dry or xeric flatwoods but now are referred to as scrubby flatwoods. Communities intermediate between scrub and high pine have been called southern ridge sandhills, hickory scrub, yellow sand scrub, turkey oak scrub, turkey oak barrens, and natural turkey oak barrens, but probably are best referred to as scrubby high pine. -

100 Years of Change in the Flora of the Carolinas

EUPHORBIACEAE 353 Tragia urticifolia Michaux, Nettleleaf Noseburn. Pd (GA, NC, SC, VA), Cp (GA, SC), Mt (SC): dry woodlands and rock outcrops, particularly over mafic or calcareous rocks; common (VA Rare). May-October. Sc. VA west to MO, KS, and CO, south to FL and AZ. [= RAB, F, G, K, W; = T. urticaefolia – S, orthographic variant] Triadica Loureiro 1790 (Chinese Tallow-tree) A genus of 2-3 species, native to tropical and subtropical Asia. The most recent monographers of Sapium and related genera (Kruijt 1996; Esser 2002) place our single naturalized species in the genus Triadica, native to Asia; Sapium (excluding Triadica) is a genus of 21 species restricted to the neotropics. This conclusion is corroborated by molecular phylogenetic analysis (Wurdack, Hoffmann, & Chase (2005). References: Kruijt (1996)=Z; Esser (2002)=Y; Govaerts, Frodin, & Radcliffe-Smith (2000)=X. * Triadica sebifera (Linnaeus) Small, Chinese Tallow-tree, Popcorn Tree. Cp (GA, NC, SC): marsh edges, shell deposits, disturbed areas; uncommon. May-June; August-November, native of e. Asia. With Euphorbia, Chamaesyce, and Cnidoscolus, one of our few Euphorbiaceous genera with milky sap. Triadica has become locally common from Colleton County, SC southward through the tidewater area of GA, and promises to become a serious weed tree (as it is in parts of LA, TX, and FL). [= K, S, X, Y, Z; = Sapium sebiferum (Linnaeus) Roxburgh – RAB, GW] Vernicia Loureiro 1790 (Tung-oil Tree) A genus of 3 species, trees, native of se. Asia. References: Govaerts, Frodin, & Radcliffe-Smith (2000)=Z. * Vernicia fordii (Hemsley) Airy-Shaw, Tung-oil Tree, Tung Tree. Cp (GA, NC): planted for the oil and for ornament, rarely naturalizing; rare, introduced from central and western China.