A Global Database of Photosynthesis Model Parameters, and Modelled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excursion Report July 2019

July 2019 Number 193 In this issue... Excursion report July 2019..................................................1 Cooktown Botanic Gardens Work Party 2019...............................1 Species List .........................................5 Australian Native Plants Society (Australia) - 2019 Conference............................................8 Excursion report Blooming Biodiversity............8 Albany, Western Australia July 2019 - 29th September to 4 October 2019..............................8 Cooktown Botanic Gardens Work Party 2019 Mystery Styphelia Update.......8 Don Lawie and Stuart Worboys What's Happening.........................9 Cooktown Botanic Gardens is Queensland's Cairns Branch.............................9 northern-most botanic gardens. Established Townsville Branch....................9 not long after the town's birth in 1873, the gardens are home to historic stone-pitched Tablelands Branch...................9 waterways. and grand and unusual heritage trees. They also lie a short distance from the Endeavour River, where in 1770 Cook beached his damaged ship for repairs after an unfortunate interaction with the Great Barrier Reef. Page 1 During their sevenSGAP Cairnsweek enforcedBranch - Newsletterstay, the 193 botanist Joseph Banks, naturalist wet season plus much work has Daniels Solander and their party resulted in a green outlook of surveyed and collected more neat graveled pathways, low key extensively than anywhere else on but effective fencing, and trees, their voyage, making Cooktown shrubs and vines all thriving and arguably the birthplace of well mulched. An efficient but Australian scientific botany. unobtrusive “pop-up” watering Since 1987, Cooktown Botanic system has assisted with Gardens has been the semi-regular maintaining growth. mid-year destination for Cairns and Tablelands branches of SGAP. Over the decades, we have assisted with tasks across the gardens, from weeding to planting, from mulching to bridge renovations. -

Foraging Modes of Carnivorous Plants Aaron M

Israel Journal of Ecology & Evolution, 2020 http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/22244662-20191066 Foraging modes of carnivorous plants Aaron M. Ellison* Harvard Forest, Harvard University, 324 North Main Street, Petersham, Massachusetts, 01366, USA Abstract Carnivorous plants are pure sit-and-wait predators: they remain rooted to a single location and depend on the abundance and movement of their prey to obtain nutrients required for growth and reproduction. Yet carnivorous plants exhibit phenotypically plastic responses to prey availability that parallel those of non-carnivorous plants to changes in light levels or soil-nutrient concentrations. The latter have been considered to be foraging behaviors, but the former have not. Here, I review aspects of foraging theory that can be profitably applied to carnivorous plants considered as sit-and-wait predators. A discussion of different strategies by which carnivorous plants attract, capture, kill, and digest prey, and subsequently acquire nutrients from them suggests that optimal foraging theory can be applied to carnivorous plants as easily as it has been applied to animals. Carnivorous plants can vary their production, placement, and types of traps; switch between capturing nutrients from leaf-derived traps and roots; temporarily activate traps in response to external cues; or cease trap production altogether. Future research on foraging strategies by carnivorous plants will yield new insights into the physiology and ecology of what Darwin called “the most wonderful plants in the world”. At the same time, inclusion of carnivorous plants into models of animal foraging behavior could lead to the development of a more general and taxonomically inclusive foraging theory. -

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

Foraging : an Ecology Model of Consumer Behaviour?

This is a repository copy of Foraging : an ecology model of consumer behaviour?. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/122432/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Wells, VK orcid.org/0000-0003-1253-7297 (2012) Foraging : an ecology model of consumer behaviour? Marketing Theory. pp. 117-136. ISSN 1741-301X https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593112441562 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Foraging: an ecology model of consumer behavior? Victoria.K.Wells* Durham Business School, UK First Submission June 2010 Revision One December 2010 Revision Two August 2011 Accepted for Publication: September 2011 * Address for correspondence: Dr Victoria Wells (née James), Durham Business School, Durham University, Mill Hill Lane, Durham, DH1 3LB & Queen’s Campus, University Boulevard, Thornaby, Stockton-on-Tees, TS17 6BH, Telephone: +44 (0)191 334 0472, E-mail: [email protected] I would like to thank Tony Ellson for his guidance and Gordon Foxall for his helpful comments during the development and writing of this paper. -

Water Stress Inhibits Plant Photosynthesis by Decreasing

letters to nature data on a variety of animals. The original foraging data on bees Acknowledgements (Fig. 3a) were collected by recording the landing sites of individual We thank V. Afanasyev, N. Dokholyan, I. P. Fittipaldi, P.Ch. Ivanov, U. Laino, L. S. Lucena, bees15. We find that, when the nectar concentration is low, the flight- E. G. Murphy, P. A. Prince, M. F. Shlesinger, B. D. Stosic and P.Trunfio for discussions, and length distribution decays as in equation (1), with m < 2 (Fig. 3b). CNPq, NSF and NIH for financial support. (The exponent m is not affected by short flights.) We also find the Correspondence should be addressed to G.M.V. (e-mail: gandhi@fis.ufal.br). value m < 2 for the foraging-time distribution of the wandering albatross6 (Fig. 3b, inset) and deer (Fig. 3c, d) in both wild and fenced areas16 (foraging times and lengths are assumed to be ................................................................. proportional). The value 2 # m # 2:5 found for amoebas4 is also consistent with the predicted Le´vy-flight motion. Water stress inhibits plant The above theoretical arguments and numerical simulations suggest that m < 2 is the optimal value for a search in any dimen- photosynthesis by decreasing sion. This is analogous to the behaviour of random walks whose mean-square displacement is proportional to the number of steps in coupling factor and ATP any dimension17. Furthermore, equations (4) and (5) describe the W. Tezara*, V. J. Mitchell†, S. D. Driscoll† & D. W. Lawlor† correct scaling properties even in the presence of short-range correlations in the directions and lengths of the flights. -

Predation Risk and Feeding Site Preferences in Winter Foraging Birds

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1992 Predation Risk and Feeding Site Preferences in Winter Foraging Birds Yen-min Kuo This research is a product of the graduate program in Zoology at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Kuo, Yen-min, "Predation Risk and Feeding Site Preferences in Winter Foraging Birds" (1992). Masters Theses. 2199. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2199 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Car1dichi.tes who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved~ we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we ~llow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library o! Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis tq a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclul!lion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ~~~~~~-~~~~~~~ Date Author m Predaton risk and feeding site preferences in winter foraging oirds (Tllll) BY Yen-min Kuo THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in Zoology IN TH£ GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVfRSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1992 YEAR I HEREBY R£COMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART or THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE 2f vov. -

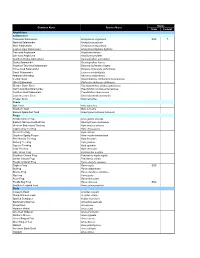

St. Joseph Bay Native Species List

Status Common Name Species Name State Federal Amphibians Salamanders Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum SSC T Marbled Salamander Ambystoma opacum Mole Salamander Ambystoma talpoideum Eastern Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum tigrinum Two-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma means One-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma pholeter Southern Dusky Salamander Desmognathus auriculatus Dusky Salamander Desmognathus fuscus Southern Two-lined Salamander Eurycea bislineata cirrigera Three-lined Salamander Eurycea longicauda guttolineata Dwarf Salamander Eurycea quadridigitata Alabama Waterdog Necturus alabamensis Central Newt Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis Slimy Salamander Plethodon glutinosus glutinosus Slender Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus spheniscus Gulf Coast Mud Salamander Pseudotriton montanus flavissimus Southern Red Salamander Pseudotriton ruber vioscai Eastern Lesser Siren Siren intermedia intermedia Greater Siren Siren lacertina Toads Oak Toad Bufo quercicus Southern Toad Bufo terrestris Eastern Spadefoot Toad Scaphiopus holbrooki holbrooki Frogs Florida Cricket Frog Acris gryllus dorsalis Eastern Narrow-mouthed Frog Gastrophryne carolinensis Western Bird-voiced Treefrog Hyla avivoca avivoca Cope's Gray Treefrog Hyla chrysoscelis Green Treefrog Hyla cinerea Southern Spring Peeper Hyla crucifer bartramiana Pine Woods Treefrog Hyla femoralis Barking Treefrog Hyla gratiosa Squirrel Treefrog Hyla squirella Gray Treefrog Hyla versicolor Little Grass Frog Limnaoedus ocularis Southern Chorus Frog Pseudacris nigrita nigrita Ornate Chorus Frog Pseudacris -

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION on the TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and Plants

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ON THE TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and plants Report prepared by John Woinarski, Kym Brennan, Ian Cowie, Raelee Kerrigan and Craig Hempel. Darwin, August 2003 Cover photo: Tall forests dominated by Darwin stringybark Eucalyptus tetrodonta, Darwin woollybutt E. miniata and Melville Island Bloodwood Corymbia nesophila are the principal landscape element across the Tiwi islands (photo: Craig Hempel). i SUMMARY The Tiwi Islands comprise two of Australia’s largest offshore islands - Bathurst (with an area of 1693 km 2) and Melville (5788 km 2) Islands. These are Aboriginal lands lying about 20 km to the north of Darwin, Northern Territory. The islands are of generally low relief with relatively simple geological patterning. They have the highest rainfall in the Northern Territory (to about 2000 mm annual average rainfall in the far north-west of Melville and north of Bathurst). The human population of about 2000 people lives mainly in the three towns of Nguiu, Milakapati and Pirlangimpi. Tall forests dominated by Eucalyptus miniata, E. tetrodonta, and Corymbia nesophila cover about 75% of the island area. These include the best developed eucalypt forests in the Northern Territory. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 1300 rainforest patches, with floristic composition in many of these patches distinct from that of the Northern Territory mainland. Although the total extent of rainforest on the Tiwi Islands is small (around 160 km 2 ), at an NT level this makes up an unusually high proportion of the landscape and comprises between 6 and 15% of the total NT rainforest extent. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 200 km 2 of “treeless plains”, a vegetation type largely restricted to these islands. -

The Effect of Season of Fire on the Recovery of Florida Scrub

2B.7 THE EFFECT OF SEASON OF FIRE ON THE RECOVERY OF FLORIDA SCRUB Tammy E. Foster* and Paul A. Schmalzer Dynamac Corporation, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 1. ABSTRACT∗ scrub, rosemary scrub, and scrubby flatwoods (Myers 1990, Abrahamson and Hartnett 1990). Florida scrub is a xeromorphic shrubland that is Florida scrub is habitat for threatened and maintained by frequent fires. Historically, these fires endangered plants and animals (Christman and Judd occurred during the summer due to lightning ignition. 1990, Stout and Marion 1993, Stout 2001). Today, Florida scrub is often managed by the use of Management of remaining scrub is critical to the survival prescribed burning. Prescribed burning of scrub has of these species. Scrub is a fire-maintained system been implemented on Kennedy Space Center/Merritt (Myers 1990, Menges 1999), and recovery after fire of Island National Wildlife Refuge (KSC/MINWR) since oak scrub and scrubby flatwoods is primarily through 1981, with burns being carried out throughout the year. sprouting and, in some species, clonal spread of the The impacts of the season of burn on recovery are not dominant shrubs (Abrahamson 1984a, 1984b, known. Long-term monitoring of scrub regeneration has Schmalzer and Hinkle 1992a, Menges and Hawkes been conducted since the early-1980’s at KSC/MINWR 1998). Scrub naturally burned during the summer using permanent 15 m line-intercept transects. We months due to lightning ignition. However, landscape obtained data from eight transects that were subjected fragmentation and fire suppression have reduced fire to a winter burn in 1986 and a summer burn in 1997 and size and frequency (Myers 1990, Duncan and compared the recovery of the stand for the first five Schmalzer 2001). -

Key to Leaves of Eastern Native Oaks

FHTET-2003-01 January 2003 Front Cover: Clockwise from top left: white oak (Q. alba) acorns; willow oak (Q. phellos) leaves and acorns; Georgia oak (Q. georgiana) leaf; chinkapin oak (Q. muehlenbergii) acorns; scarlet oak (Q. coccinea) leaf; Texas live oak (Q. fusiformis) acorns; runner oak (Q. pumila) leaves and acorns; background bur oak (Q. macrocarpa) bark. (Design, D. Binion) Back Cover: Swamp chestnut oak (Q. michauxii) leaves and acorns. (Design, D. Binion) FOREST HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ENTERPRISE TEAM TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Oak Identification Field Guide to Native Oak Species of Eastern North America John Stein and Denise Binion Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield St., Morgantown, WV 26505 Robert Acciavatti Forest Health Protection Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield St., Morgantown, WV 26505 United States Forest FHTET-2003-01 Department of Service January 2003 Agriculture NORTH AMERICA 100th Meridian ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank all those who helped with this publication. We are grateful for permission to use the drawings illustrated by John K. Myers, Flagstaff, AZ, published in the Flora of North America, North of Mexico, vol. 3 (Jensen 1997). We thank Drs. Cynthia Huebner and Jim Colbert, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Disturbance Ecology and Management of Oak-Dominated Forests, Morgantown, WV; Dr. Martin MacKenzie, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection, Morgantown, WV; Dr. Steven L. Stephenson, Department of Biology, Fairmont State College, Fairmont, WV; Dr. Donna Ford-Werntz, Eberly College of Arts and Sciences, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV; Dr. -

Northern Yellow Bat Roost Selection and Fidelity in South Carolina

Final Report South Carolina State Wildlife Grant SC T-F16AF00598 South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) May 1, 2016-June 30, 2017 Project Title: Northern Yellow Bat Roost Selection and Fidelity in South Carolina Mary Socci, Palmetto Bluff Conservancy (PBC), Jay Walea, PBC, Timothy White, PBC, Jason Robinson, Biological Systems Consultants, Inc., and Jennifer Kindel, SCDNR Objective 1: Radio-track healthy Northern yellow bats (≤ 10) captured by mist netting appropriate habitat in spring, summer, and fall 2016, ideally with at least 3 radio-tracking events in each season. Record roost switching, and describe roost sites selected. Accomplishments: Introduction: The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the roost site selection and fidelity of northern yellow bats (Lasiurus intermedius, syn. Dasypterus intermedius) by capturing, radio- tagging and tracking individual L. intermedius at Palmetto Bluff, a 15,000 acre, partially-developed tract in Beaufort County, South Carolina (Figures 1 and 2). Other objectives (2 and 3) were to obtain audio recordings of bats foraging in various habitats across the Palmetto Bluff property, including as many L. intermedius as possible and to initiate a public outreach program in order to educate the community on both the project and the environmental needs of bats, many of which are swiftly declining species in United States. Figure 1. Location of Palmetto Bluff 1 Figure 2. The Palmetto Bluff Development Tract The life history of northern yellow bats, a high-priority species in the Southeast, is poorly understood. Studies in coastal Georgia found that all yellow bats that were tracked roosted in Spanish moss in southern live oaks (Quercus virginiana) and sand live oaks (Quercus geminata) (Coleman et al. -

Guava (Eucalyptus) Rust Puccinia Psidii

INDUSTRY BIOSECURITY PLAN FOR THE NURSERY & GARDEN INDUSTRY Threat Specific Contingency Plan Guava (eucalyptus) rust Puccinia psidii Plant Health Australia March 2009 Disclaimer The scientific and technical content of this document is current to the date published and all efforts were made to obtain relevant and published information on the pest. New information will be included as it becomes available, or when the document is reviewed. The material contained in this publication is produced for general information only. It is not intended as professional advice on any particular matter. No person should act or fail to act on the basis of any material contained in this publication without first obtaining specific, independent professional advice. Plant Health Australia and all persons acting for Plant Health Australia in preparing this publication, expressly disclaim all and any liability to any persons in respect of anything done by any such person in reliance, whether in whole or in part, on this publication. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of Plant Health Australia. Further information For further information regarding this contingency plan, contact Plant Health Australia through the details below. Address: Suite 5, FECCA House 4 Phipps Close DEAKIN ACT 2600 Phone: +61 2 6215 7700 Fax: +61 2 6260 4321 Email: [email protected] Website: www.planthealthaustralia.com.au PHA & NGIA | Contingency Plan – Guava rust (Puccinia psidii) 1 Purpose and background of this contingency plan .............................................................