The Effect of Season of Fire on the Recovery of Florida Scrub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Harney Wilderness Area Land Management Plan

Lake Harney Wilderness Area Land Management Plan 2010 LAKE HARNEY WILDERNESS AREA LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 WILDERNESS AREA OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................................. 1 REGIONAL SIGNIFICANCE .................................................................................................................................................. 1 ACQUISITION HISTORY ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 NATURAL RESOURCES OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................... 4 NATURAL COMMUNITIES.................................................................................................................................................. 4 FIRE ............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 WILDLIFE ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 EXOTICS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Burn Severity in a Central Florida Sand Pine Scrub Wilderness Area

BURN SEVERITY IN A CENTRAL FLORIDA SAND PINE SCRUB WILDERNESS AREA By DAVID ROBERT GODWIN A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 David Robert Godwin 2 To my family and grandparents who have worked tirelessly to provide for my education and who instilled in me an interest in the natural world. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study would not have been possible without the encouragement, support, and guidance of my major professor (Dr. Leda Kobziar) and my supervisory committee members (Dr. Scot Smith and Dr. George Tanner). This research was funded by a grant from the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) Innovation Fund entitled: “Fire in The Juniper Prairie Wilderness: A Viable Management Tool?” Data analysis assistance was graciously provided by Dr. Leda Kobziar and Meghan Brennan, IFAS Statistics Department. Field data were collected through the tireless assistance of University of Florida Fire Science Lab technicians and students: Erin Maehr, Mia Requensens, Chris Kinslow and Cori Peters. Remote sensing software guidance and meticulous digital aerial imagery delineations were provided by Zoltan Szantoi, with help from Dr. Alan Long and Dr. Leda Kobziar. Some spatial data were provided by the Ocala National Forest, USDA Forest Service, through the assistance of Mike Drayton and Janet Hinchee. SPOT images were purchased through funds provided by Dr. Scott Smith. Landsat images were obtained from the Multi- Resolution Land Characteristics Consortium (MRLC). Finally, I thank my loving wife, brother, parents and grandparents for their patience, encouragement and dedication to my completion of this study. -

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

(Fabaceae) at Wild and Introduced Locations in Florida Scrub

Plant Ecol DOI 10.1007/s11258-014-0310-6 Microhabitat of critically endangered Lupinus aridorum (Fabaceae) at wild and introduced locations in Florida scrub Matthew L. Richardson • Juliet Rynear • Cheryl L. Peterson Received: 23 September 2013 / Accepted: 30 January 2014 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht (outside the USA) 2014 Abstract Elucidating microhabitat preferences of a Our research determined that L. aridorum is diploid and rare species are critical for its conservation. Lupinus grew, on average, in areas closer to trees and shrubs, aridorum McFarlin ex Beckner (Fabaceae) is a critically with lower soil moisture, and with a greater mixture of endangered plant known only from a few locations in detritus than random locations. Some microhabitat imperiled Florida scrub habitat and nothing is known characteristics at locations where L. aridorum were about its preferred microhabitat. Our goals were three- introduced were similar to microhabitat supporting wild fold. First, determine whether L. aridorum has multiple L. aridorum, but multiple soil characteristics differed as cytotypes because this can influence its spatial distribu- did the plant community, which contained more non- tion. Second, measure how microhabitat characteristics native plant species near introduced plants. Therefore, at locations supporting wild L. aridorum vary from the realized niche is narrower than the fundamental random locations, which will provide information about niche. Overall, information about the microhabitat of microhabitat characteristics that influence the spatial L. aridorum canbeusedtodesignappropriatemanage- distribution of individuals. Third, measure whether ment programs to conserve and restore populations of microhabitat characteristics differ between locations this plant species and species that occupy a similar niche supporting wild or introduced plants, which will provide in imperiled Florida scrub. -

Ecological Summary Report

Ecological Summary Report 56.8-acre Ameratrail Property Section 14, Township 26 South, Range 31 East Osceola County, Florida Prepared for: Snow Construction, Inc. 1136 New York Avenue St Cloud, FL 34769 October 2018 Table of Contents 1.0 Property Location 1 2.0 Survey Methodology 1 3.0 Soils 1 4.0 Vegetative Communities 2 5.0 Listed Wildlife Species 3 5.1 Bald Eagle 3 5.2 Gopher Tortoise 3 5.3 Red Cockaded Woodpecker 3 5.4 Florida Scrub-Jay 3 5.5 Eastern Indigo Snake 3 6.0 Ecological Impact Analysis 4 7.0 Conclusion 4 List of Figures: Figure 1 – Location Map Figure 2 – Aerial Photograph Figure 3 – USDA Soils Map Figure 4 – FLUCFCS Map This report presents the results of an ecological impact analysis for the Ameratrail project. The purpose of this analysis is to document existing site conditions, and the extent of impacts to jurisdictional wetlands and surface waters, as well as state and federally-listed species and their habitats. This information is intended to support Environmental Resource Permitting through the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD). 1.0 PROPERTY LOCATION The property consists of approximately 56.8 acres and is located southeast of the intersection of Old Melbourne Highway and US Highway 192 within Section 14, Township 26 South, Range 31 East, in Osceola County. The property consists of Osceola County tax parcel 14-26-31-0000-0010-0000. A location map and an aerial photograph have been provided as Figures 1 and 2, respectively. 2.0 SURVEY METHODOLOGY Prior to visiting the site, Austin Environmental Consultants, Inc. -

St. Joseph Bay Native Species List

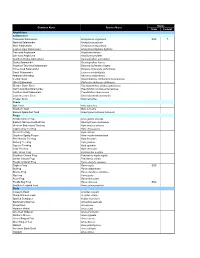

Status Common Name Species Name State Federal Amphibians Salamanders Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum SSC T Marbled Salamander Ambystoma opacum Mole Salamander Ambystoma talpoideum Eastern Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum tigrinum Two-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma means One-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma pholeter Southern Dusky Salamander Desmognathus auriculatus Dusky Salamander Desmognathus fuscus Southern Two-lined Salamander Eurycea bislineata cirrigera Three-lined Salamander Eurycea longicauda guttolineata Dwarf Salamander Eurycea quadridigitata Alabama Waterdog Necturus alabamensis Central Newt Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis Slimy Salamander Plethodon glutinosus glutinosus Slender Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus spheniscus Gulf Coast Mud Salamander Pseudotriton montanus flavissimus Southern Red Salamander Pseudotriton ruber vioscai Eastern Lesser Siren Siren intermedia intermedia Greater Siren Siren lacertina Toads Oak Toad Bufo quercicus Southern Toad Bufo terrestris Eastern Spadefoot Toad Scaphiopus holbrooki holbrooki Frogs Florida Cricket Frog Acris gryllus dorsalis Eastern Narrow-mouthed Frog Gastrophryne carolinensis Western Bird-voiced Treefrog Hyla avivoca avivoca Cope's Gray Treefrog Hyla chrysoscelis Green Treefrog Hyla cinerea Southern Spring Peeper Hyla crucifer bartramiana Pine Woods Treefrog Hyla femoralis Barking Treefrog Hyla gratiosa Squirrel Treefrog Hyla squirella Gray Treefrog Hyla versicolor Little Grass Frog Limnaoedus ocularis Southern Chorus Frog Pseudacris nigrita nigrita Ornate Chorus Frog Pseudacris -

ATLAS of FLORIDA PLANTS - 7/29/19 Lake County Native Species

ATLAS OF FLORIDA PLANTS - 7/29/19 Lake County Native Species Scientific_Name Common_Name Endemic State US 1 Abutilon hulseanum MAUVE N 2 Acalypha gracilens SLENDER THREESEED MERCURY N 3 Acalypha ostryifolia PINELAND THREESEED MERCURY N 4 Acer negundo BOXELDER N 5 Acer rubrum RED MAPLE N 6 Acrolejeunea heterophylla 7 Acrostichum danaeifolium GIANT LEATHER FERN N 8 Aeschynomene americana SHYLEAF N 9 Aeschynomene viscidula STICKY JOINTVETCH N 10 Aesculus pavia RED BUCKEYE N 11 Agalinis fasciculata BEACH FALSE FOXGLOVE N 12 Agalinis filifolia SEMINOLE FALSE FOXGLOVE N 13 Agalinis linifolia FLAXLEAF FALSE FOXGLOVE N 14 Agalinis plukenetii PLUKENET'S FALSE FOXGLOVE N 15 Agarista populifolia FLORIDA HOBBLEBUSH; PIPESTEM N 16 Ageratina jucunda HAMMOCK SNAKEROOT N 17 Aletris lutea YELLOW COLICROOT N 18 Allium canadense var. canadense MEADOW GARLIC N 19 Amaranthus australis SOUTHERN AMARANTH N 20 Amblystegium serpens 21 Ambrosia artemisiifolia COMMON RAGWEED N 22 Amorpha fruticosa BASTARD FALSE INDIGO N 23 Amorpha herbacea var. herbacea CLUSTERSPIKE FALSE INDIGO N 24 Amphicarpum muehlenbergianum BLUE MAIDENCANE N 25 Amsonia ciliata FRINGED BLUESTAR N 26 Andropogon brachystachyus SHORTSPIKE BLUESTEM N 27 Andropogon floridanus FLORIDA BLUESTEM N 28 Andropogon glomeratus var. glaucopsis PURPLE BLUESTEM N 29 Andropogon glomeratus var. hirsutior BUSHY BLUESTEM N 30 Andropogon glomeratus var. pumilus BUSHY BLUESTEM N 31 Andropogon gyrans ELLIOTT'S BLUESTEM N 32 Andropogon longiberbis HAIRY BLUESTEM N 33 Andropogon ternarius SPLITBEARD BLUESTEM N 34 Andropogon -

Northern Yellow Bat Roost Selection and Fidelity in South Carolina

Final Report South Carolina State Wildlife Grant SC T-F16AF00598 South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) May 1, 2016-June 30, 2017 Project Title: Northern Yellow Bat Roost Selection and Fidelity in South Carolina Mary Socci, Palmetto Bluff Conservancy (PBC), Jay Walea, PBC, Timothy White, PBC, Jason Robinson, Biological Systems Consultants, Inc., and Jennifer Kindel, SCDNR Objective 1: Radio-track healthy Northern yellow bats (≤ 10) captured by mist netting appropriate habitat in spring, summer, and fall 2016, ideally with at least 3 radio-tracking events in each season. Record roost switching, and describe roost sites selected. Accomplishments: Introduction: The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the roost site selection and fidelity of northern yellow bats (Lasiurus intermedius, syn. Dasypterus intermedius) by capturing, radio- tagging and tracking individual L. intermedius at Palmetto Bluff, a 15,000 acre, partially-developed tract in Beaufort County, South Carolina (Figures 1 and 2). Other objectives (2 and 3) were to obtain audio recordings of bats foraging in various habitats across the Palmetto Bluff property, including as many L. intermedius as possible and to initiate a public outreach program in order to educate the community on both the project and the environmental needs of bats, many of which are swiftly declining species in United States. Figure 1. Location of Palmetto Bluff 1 Figure 2. The Palmetto Bluff Development Tract The life history of northern yellow bats, a high-priority species in the Southeast, is poorly understood. Studies in coastal Georgia found that all yellow bats that were tracked roosted in Spanish moss in southern live oaks (Quercus virginiana) and sand live oaks (Quercus geminata) (Coleman et al. -

Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources: Forest Trees

Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources . Chittaranjan Kole Editor Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources Forest Trees Editor Prof. Chittaranjan Kole Director of Research Institute of Nutraceutical Research Clemson University 109 Jordan Hall Clemson, SC 29634 [email protected] ISBN 978-3-642-21249-9 e-ISBN 978-3-642-21250-5 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-21250-5 Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922649 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2011 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: deblik, Berlin Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Dedication Dr. Norman Ernest Borlaug,1 the Father of Green Revolution, is well respected for his contribu- tions to science and society. There was or is not and never will be a single person on this Earth whose single-handed service to science could save millions of people from death due to starvation over a period of over four decades like Dr. -

The Clonal Structure of Quercus Geminata Revealed by Conserved

Molecular Ecology (2003) 12, 527–532 TheBlackwell Science, Ltd clonal structure of Quercus geminata revealed by conserved microsatellite loci E. A. AINSWORTH,* P. J. TRANEL,* B. G. DRAKE† and S. P. LONG*‡ Departments of *Crop Sciences and of ‡Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, 1201 W. Gregory Drive, Urbana, IL 61801, USA; †Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Edgewater, MD, USA Abstract The scrub oak communities of the southeastern USA may have existed at their present loca- tions for thousands of years. These oaks form suckers, and excavations of root systems sug- gest that clones may occupy very large areas. Resolution of the clonal nature of scrub oaks is important both to manage the tracts of this ecosystem that remain, and in conducting long-term ecological studies, where the study area must substantially exceed the area occu- pied by any single clone. Microsatellites were used to determine the genetic diversity of a dominant oak species within a 2-ha long-term experimental site on Merritt Island at the Kennedy Space Center. This area contains a long-term study of the effects of elevated CO2 on the ecosystem. Conservation of seven microsatellite loci, previously identified in the sessile oak, Quercus petraea, was tested in two Florida scrub oak species, Q. geminata and Q. myrtifolia. Sequence analysis revealed that all seven microsatellite loci were conserved in Q. geminata and five loci were conserved in Q. myrtifolia. Six microsatellite loci were polymorphic in Q. geminata and these were subsequently used to investigate the clonal structure of the Q. geminata population. Twenty-one unique combinations of microsatellites, or haplotypes, occurred only once, whereas the remaining 26 individuals belonged to a total of seven different haplotypes. -

Lyonia Preserve Plant Checklist

I -1 Lyonia Preserve Plant Checklist Volusia County, Florida I, I Aceraceae (Maple) Asteraceae (Aster) Red Maple Acer rubrum • Bitterweed Helenium amarum • Blackroot Pterocaulon virgatum Agavaceae (Yucca) Blazing Star Liatris sp. B Adam's Needle Yucca filamentosa Blazing Star Liatris tenuifolia BNolina Nolina brittoniana Camphorweed Heterotheca subaxillaris Spanish Bayonet Yucca aloifolia § Cudweed Gnaphalium falcatum • Dog Fennel Eupatorium capillifolium Amaranthaceae (Amaranth) Dwarf Horseweed Conyza candensis B Cottonweed Froelichia floridana False Dandelion Pyrrhopappus carolinianus • Fireweed Erechtites hieracifolia B Anacardiaceae (Cashew) Garberia Garberia heterophylla Winged Sumac Rhus copallina Goldenaster Pityopsis graminifolia • § Goldenrod Solidago chapmanii Annonaceae (Custard Apple) Goldenrod Solidago fistulosa Flag Paw paw Asimina obovata Goldenrod Solidago spp. B • Mohr's Throughwort Eupatorium mohrii Apiaceae (Celery) BRa gweed Ambrosia artemisiifolia • Dollarweed Hydrocotyle sp. Saltbush Baccharis halimifolia BSpanish Needles Bidens alba Apocynaceae (Dogbane) Wild Lettuce Lactuca graminifolia Periwinkle Catharathus roseus • • Brassicaceae (Mustard) Aquifoliaceae (Holly) Poorman's Pepper Lepidium virginicum Gallberry Ilex glabra • Sand Holly Ilex ambigua Bromeliaceae (Airplant) § Scrub Holly Ilex opaca var. arenicola Ball Moss Tillandsia recurvata • Spanish Moss Tillandsia usneoides Arecaceae (Palm) • Saw Palmetto Serenoa repens Cactaceae (Cactus) BScrub Palmetto Sabal etonia • Prickly Pear Opuntia humifusa Asclepiadaceae -

Growth and Recovery of Oak-Saw Palmetto Scrub Through Ten Years After Fire Paul A

Growth and Recovery of Oak-Saw Palmetto Scrub through Ten Years After Fire Paul A. SChmalzer RESEARCH ARTICLE ABSTRACT: Oak-saw palmetto scrub, a shrub community of acid, sandy, well-drained soils in Florida, is maintained by periodic, intense fIre. Understanding the direction and rates of changes in scrub composition and structure after fire is important to management decisions. We followed changes in vegeta.tion along 15Cm linecintercepttransects that were established in 1983. Two stands (8 transects) burned in a prescribed fire in December 1986; the stands had previously burned 11 y (N=4) and 7 y (N=4) before. We sampled transects at 6, 12, 18, and 24 rna and then annually through 10 y after the • 1986 fire. We measured cover by species in two height classes, > 0.5 m and < 0.5 m, and measured height at four points (0, 5, 10, and 15 m) along each transect. Saw palmetto cover equaled preburn values by· one year postburn and changed little after that. Cover of oaks > 0.5 m (Quercus myrtifolia, Q. Growth and geminata, Q. chapmanii) equaled preburn values by 5 y postburn and changed little by 10 Y postburn. Height growth continued, increasing from a mean of 84.0 cm at 5 y to 125.9 cm at 10 y postburn. Bare ground declined to <2% by 3 Y postburn. Plant species richness increased slightly after fire and then Recovery of Oak gradually declined. These vegetation changes alter habitat conditions for threatened and endangered Saw Pal metto Scrub animals and plants. Crecimiento y Recuperaci6n del 'Oak-Saw Palmetto Scrub' Durante Diez Anos through Ten Years Despues del Fuego RESUMEN: EI 'Oak-saw palmetto scrub' es una comunidad de arbustos de suelos :kidos, arenosos y After Fire bien drenados en Florida, mantenidos por fuegos peri6dicos e intensos.