An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

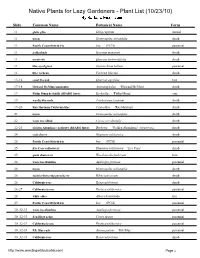

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10)

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10) Slide Common Name Botanical Name Form 11 globe gilia Gilia capitata annual 11 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 11 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 11 goldenbush Isocoma menziesii shrub 11 scrub oak Quercus berberidifolia shrub 11 blue-eyed grass Sisyrinchium bellum perennial 11 lilac verbena Verbena lilacina shrub 13-16 coast live oak Quercus agrifolia tree 17-18 Howard McMinn man anita Arctostaphylos 'Howard McMinn' shrub 19 Philip Mun keckiella (RSABG Intro) Keckiella 'Philip Munz' ine 19 woolly bluecurls Trichostema lanatum shrub 19-20 Ray Hartman California lilac Ceanothus 'Ray Hartman' shrub 21 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 22 western redbud Cercis occidentalis shrub 22-23 Golden Abundance barberry (RSABG Intro) Berberis 'Golden Abundance' (MAHONIA) shrub 2, coffeeberry Rhamnus californica shrub 25 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 25 Eve Case coffeeberry Rhamnus californica '. e Case' shrub 25 giant chain fern Woodwardia fimbriata fern 26 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 26 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 26 fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 26 California rose Rosa californica shrub 26-27 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 28 white alder Alnus rhombifolia tree 29 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 30 032-33 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 30 032-33 San Diego sedge Carex spissa perennial 30 032-33 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 30 032-33 Elk Blue rush Juncus patens '.l1 2lue' perennial 30 032-33 California rose Rosa californica shrub http://www weedingwildsuburbia com/ Page 1 30 032-3, toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 30 032-3, fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 30 032-3, Claremont pink-flowering currant (RSA Intro) Ribes sanguineum ar. -

Annotated Check List and Host Index Arizona Wood

Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood-Rotting Fungi Item Type text; Book Authors Gilbertson, R. L.; Martin, K. J.; Lindsey, J. P. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 28/09/2021 02:18:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/602154 Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood - Rotting Fungi Technical Bulletin 209 Agricultural Experiment Station The University of Arizona Tucson AÏfJ\fOTA TED CHECK LI5T aid HOST INDEX ford ARIZONA WOOD- ROTTlNg FUNGI /. L. GILßERTSON K.T IyIARTiN Z J. P, LINDSEY3 PRDFE550I of PLANT PATHOLOgY 2GRADUATE ASSISTANT in I?ESEARCI-4 36FZADAATE A5 S /STANT'" TEACHING Z z l'9 FR5 1974- INTRODUCTION flora similar to that of the Gulf Coast and the southeastern United States is found. Here the major tree species include hardwoods such as Arizona is characterized by a wide variety of Arizona sycamore, Arizona black walnut, oaks, ecological zones from Sonoran Desert to alpine velvet ash, Fremont cottonwood, willows, and tundra. This environmental diversity has resulted mesquite. Some conifers, including Chihuahua pine, in a rich flora of woody plants in the state. De- Apache pine, pinyons, junipers, and Arizona cypress tailed accounts of the vegetation of Arizona have also occur in association with these hardwoods. appeared in a number of publications, including Arizona fungi typical of the southeastern flora those of Benson and Darrow (1954), Nichol (1952), include Fomitopsis ulmaria, Donkia pulcherrima, Kearney and Peebles (1969), Shreve and Wiggins Tyromyces palustris, Lopharia crassa, Inonotus (1964), Lowe (1972), and Hastings et al. -

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens Francisco Garin Garcia Iturraran Botanical Gardens, northern Spain [email protected] Overview Iturraran Botanical Gardens occupy 25 hectares of the northern area of Spain’s Pagoeta Natural Park. They extend along the slopes of the Iturraran hill upon the former hay meadows belonging to the farmhouse of the same name, currently the Reception Centre of the Park. The minimum altitude is 130 m above sea level, and the maximum is 220 m. Within its bounds there are indigenous wooded copses of Quercus robur and other non-coniferous species. Annual precipitation ranges from 140 to 160 cm/year. The maximum temperatures can reach 30º C on some days of summer and even during periods of southern winds on isolated days from October to March; the winter minimums fall to -3º C or -5 º C, occasionally registering as low as -7º C. Frosty days are few and they do not last long. It may snow several days each year. Soils are fairly shallow, with a calcareous substratum, but acidified by the abundant rainfall. In general, the pH is neutral due to their action. Collections The first plantations date back to late 1987. There are currently approximately 5,000 different taxa, the majority being trees and shrubs. There are around 3,000 species, including around 300 species from the genus Quercus; 100 of them are from Mexico and Central America. Quercus costaricensis photo©Francisco Garcia 48 International Oak Journal No. 22 Spring 2011 Oaks from Mexico and Oaks from Mexico -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Diversidad Del Género Quercus (Fagaceae) En México

Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México 75: 33-53, 2004 DOI: 10.17129/botsci.1692 Bol.Soc.Bot.Méx. 75: 33-53 (2004) SISTEMÁTICA Y FLORÍSTICA DIVERSIDAD DEL GÉNERO QUERCUS (FAGACEAE) EN MÉXICO SUSANA VALENCIA-A. Herbario de la Facultad de Ciencias (FCME), Departamento de Biología Comparada, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, México, 04510, México D.F. Correo-e: [email protected] Resumen: Se presenta una lista preliminar de 161 especies del género Quercus para México, ubicadas en tres secciones: 76 en la sección Lobatae (encinos rojos), 81 en la sección Quercus (encinos blancos) y cuatro especies en la sección Protobalanus (encinos intermedios). Se calcula que 109 especies son endémicas del país, de las cuales 47 pertenecen a la sección Quercus, 61 a la sección Lobatae y una a Protobalanus. México comparte con Estados Unidos 33 especies del género, mientras que con Centroamérica com- parte 20. Los estados con mayor diversidad de especies son Oaxaca, Nuevo León, Jalisco, Chihuahua y Veracruz. Las especies con distribución más amplia en nuestro país son Q. candicans, Q. castanea, Q. crassifolia, Q. laeta, Q. microphylla, Q. obtusata y Q. rugosa. Altitudinalmente las especies de Quercus se desarrollan entre 0 y 3,500 m, pero son más frecuentes entre 1,000 y 3,000 m. El conocimiento del género Quercus en México es aún deficiente y se necesita realizar más estudios en torno a este importante género. P alabras clave: di versidad, encino, endemismo, México, Quercus. Abstract: This study presents a preliminary list of 161 species from the genus Quercus, all native to Mexico. -

Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site

Powell, Schmidt, Halvorson In Cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Plant and Vertebrate Vascular U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Open-File Report 2005-1167 Southwest Biological Science Center Open-File Report 2005-1167 February 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Park Service In cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site By Brian F. Powell, Cecilia A. Schmidt , and William L. Halvorson Open-File Report 2005-1167 December 2006 USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Sonoran Desert Research Station University of Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior School of Natural Resources U.S. Geological Survey 125 Biological Sciences East National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85721 U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS-the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web:http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested Citation Powell, B. F, C. A. Schmidt, and W. L. Halvorson. 2006. Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site. -

Adenostoma Fasciculatum Profile to Postv2.Xlsx

I. SPECIES Adenostoma fasciculatum Hooker & Arnott NRCS CODE: ADFA Family: Rosaceae A. f. var. obtusifolium, Ron A. f. var. fasciculatum., Riverside Co., A. Montalvo, RCRCD Vanderhoff (Creative Order: Rosales Commons CC) Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida A. Subspecific taxa 1. Adenostoma fasciculatum var. fasciculatum Hook. & Arn. 1. ADFAF 2. A. f. var. obusifolium S. Watson 2. ADFAO 3. A. f. var. prostratum Dunkle 3. (no NRCS code) B. Synonyms 1. A. f. var. densifolium Eastw. 2. A. brevifolium Nutt. 3. none. Formerly included as part of A. f. var. f. C. Common name 1. chamise, common chamise, California greasewood, greasewood, chamiso (Painter 2016) 2. San Diego chamise (Calflora 2016) 3. prostrate chamise (Calflora 2016) Phylogenetic studies using molecular sequence data placedAdenostoma closest to Chamaebatiaria and D. Taxonomic relationships Sorbaria (Morgan et al. 1994, Potter et al. 2007) and suggest tentative placement in subfamily Spiraeoideae, tribe Sorbarieae (Potter et al. 2007). E. Related taxa in region Adenostoma sparsifolium Torrey, known as ribbon-wood or red-shanks is the only other species of Adenostoma in California. It is a much taller, erect to spreading shrub of chaparral vegetation, often 2–6 m tall and has a more restricted distribution than A. fasciculatum. It occurs from San Luis Obispo Co. south into Baja California. Red-shanks produces longer, linear leaves on slender long shoots rather than having leaves clustered on short shoots (lacks "fascicled" leaves). Its bark is cinnamon-colored and in papery layers that sheds in long ribbons. F. Taxonomic issues The Jepson eFlora and the FNA recognize A. f. var. prostratum but the taxon is not recognized by USDA PLANTS (2016). -

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids . oaks, birches, evening primroses . a major group of the woody plants (trees/shrubs) present at your sites The Wind Pollinated Trees • Alternate leaved tree families • Wind pollinated with ament/catkin inflorescences • Nut fruits = 1 seeded, unilocular, indehiscent (example - acorn) *Juglandaceae - walnut family Well known family containing walnuts, hickories, and pecans Only 7 genera and ca. 50 species worldwide, with only 2 genera and 4 species in Wisconsin Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Leaves pinnately compound, alternate (walnuts have smallest leaflets at tip) Leaves often aromatic from resinous peltate glands; allelopathic to other plants Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family The chambered pith in center of young stems in Juglans (walnuts) separates it from un- chambered pith in Carya (hickories) Juglans regia English walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Trees are monoecious Wind pollinated Female flower Male inflorescence Juglans nigra Black walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Male flowers apetalous and arranged in pendulous (drooping) catkins or aments on last year’s woody growth Calyx small; each flower with a bract CA 3-6 CO 0 A 3-∞ G 0 Juglans cinera Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Female flowers apetalous and terminal Calyx cup-shaped and persistant; 2 stigma feathery; bracted CA (4) CO 0 A 0 G (2-3) Juglans cinera Juglans nigra Butternut, white -

Key to Leaves of Eastern Native Oaks

FHTET-2003-01 January 2003 Front Cover: Clockwise from top left: white oak (Q. alba) acorns; willow oak (Q. phellos) leaves and acorns; Georgia oak (Q. georgiana) leaf; chinkapin oak (Q. muehlenbergii) acorns; scarlet oak (Q. coccinea) leaf; Texas live oak (Q. fusiformis) acorns; runner oak (Q. pumila) leaves and acorns; background bur oak (Q. macrocarpa) bark. (Design, D. Binion) Back Cover: Swamp chestnut oak (Q. michauxii) leaves and acorns. (Design, D. Binion) FOREST HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ENTERPRISE TEAM TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Oak Identification Field Guide to Native Oak Species of Eastern North America John Stein and Denise Binion Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield St., Morgantown, WV 26505 Robert Acciavatti Forest Health Protection Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield St., Morgantown, WV 26505 United States Forest FHTET-2003-01 Department of Service January 2003 Agriculture NORTH AMERICA 100th Meridian ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank all those who helped with this publication. We are grateful for permission to use the drawings illustrated by John K. Myers, Flagstaff, AZ, published in the Flora of North America, North of Mexico, vol. 3 (Jensen 1997). We thank Drs. Cynthia Huebner and Jim Colbert, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Disturbance Ecology and Management of Oak-Dominated Forests, Morgantown, WV; Dr. Martin MacKenzie, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection, Morgantown, WV; Dr. Steven L. Stephenson, Department of Biology, Fairmont State College, Fairmont, WV; Dr. Donna Ford-Werntz, Eberly College of Arts and Sciences, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV; Dr. -

Geology As a Georegional Influence on Quercus Fagaceae Distribution

GEOLOGY AS A GEOREGIONAL INFLUENCE ON Quercus FAGACEAE DISTRIBUTION IN DENTON AND COKE COUNTIES OF CENTRAL AND NORTH CENTRAL TEXAS AND CHOCTAW COUNTY OF SOUTHEASTERN OKLAHOMA, USING GIS AS AN ANALYTICAL TOOL George F. Maxey, B.S., M.S. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2007 APPROVED: C. Reid Ferring, Major Professor Miguel Avevedo, Committee Member Kenneth Dickson, Committee Member Donald Lyons, Committee Member Paul Hudak, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Geography Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Maxey, George F. Geology as a Georegional Influence on Quercus Fagaceae Distribution in Denton and Coke Counties of Central and North Central Texas and Choctaw County of Southeastern Oklahoma, Using GIS as an Analytical Tool. Doctor of Philosophy (Environmental Science), December 2007, 198 pp., 30 figures, 24 tables, references, 57 titles. This study elucidates the underlying relationships for the distribution of oak landcover on bedrock and soil orders in two counties in Texas and one in Oklahoma. ESRI’s ArcGis and ArcMap was used to create surface maps for Denton and Coke Counties, Texas and Choctaw County, Oklahoma. Attribute tables generated in GIS were exported into a spreadsheet software program and frequency tables were created for every formation and soil order in the tri-county research area. The results were both a visual and numeric distribution of oaks in the transition area between the eastern hardwood forests and the Great Plains. Oak distributions are changing on this transition area of the South Central Plains. -

Redalyc.Los Usos No Leñosos De Los Encinos En México

Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México ISSN: 0366-2128 [email protected] Sociedad Botánica de México México Luna José, Azucena de Lourdes; Montalvo Espinosa, Linda; Rendón Aguilar, Beatriz Los usos no leñosos de los encinos en México Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, núm. 72, junio, 2003, pp. 107-117 Sociedad Botánica de México Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57707204 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Bol. Soc. Bot. Méx. 72: 107-117 (2003) BOTÁNICA ECONÓMICA Y ETNOBOTÁNICA LOS USOS NO LEÑOSOS DE LOS ENCINOS EN MÉXICO AZUCENA DE LOURDES LUNA-JOSÉ1, LINDA MONTALVO-ESPINOSA1 Y BEATRIZ RENDÓN-AGUILAR2 1Colegio de Posgraduados, Montecillos, México 2Departamento de Biología, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa. A.P. 55-535. México, D.F. C.P. 09340. Fax 58-04-46-88. Correo-e: [email protected] Resumen: Se presenta una revisión bibliográfica y de herbario de los usos no leñosos de algunos encinos en México. Cincuenta y cinco especies de Quercus se utilizan y obtienen exclusivamente mediante la recolección. La mayoría se emplea en los estados ubicados en el centro y sur del país. No se encontró una relación entre el número de especies utilizadas y la diversidad de especies por estado. Se registraron cinco categorías de uso: (1) medicinal, que se relaciona principalmente con problemas del aparato digestivo; (2) alimenticio, que comprende la elaboración y consumo de alimento fresco o procesado; (3) artesanal, para la elaboración de diferentes artículos como rosarios o juguetes; (4) forraje, principalmente para la alimentación de ganado porcino y caprino; (5) taninos y colorantes, para curtir piel, como mordiente y para teñir hilo.