Syi'r, Syair, Syi'iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE JAVANESE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMED IN THE CLASSIC PALACE STYLE: AN ANALYSIS OF RAMA’S CROWN AS TOLD BY KI PURBO ASMORO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By GUAN YU, LAM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 JAVANESE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMED IN THE CLASSIC PALACE STYLE: AN ANALYSIS OF RAMA’S CROWN AS TOLD BY KI PURBO ASMORO A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Paula Conlon, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ______________________________ Dr. Marvin Lamb © Copyright by GUAN YU, LAM 2016 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would like to take this opportunity to thank the members of my committee: Dr. Paula Conlon, Dr. Eugene Enrico, and Dr. Marvin Lamb for their guidance and suggestions in the preparation of this thesis. I would especially like to thank Dr. Paula Conlon, who served as chair of the committee, for the many hours of reading, editing, and encouragement. I would also like to thank Wong Fei Yang, Thow Xin Wei, and Agustinus Handi for selflessly sharing their knowledge and helping to guide me as I prepared this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their continued support throughout this process. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................... -

Sociology of Literature Approach

ISSN: 2186-8492, ISSN: 2186-8484 Print Vol. 2 No. 3 August 2013 ASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN JAVANESE POETRY AND JAVANESE TEMBANG FOR THE LINGUISTIC EDUCATION PROGRAM: SOCIOLOGY OF LITERATURE APPROACH Herman J. Waluyo 1, Sahid Teguh Widodo 2, Y. Slamet 3 Universitas Sebelas Maret, Solo, INDONESIA. 1 [email protected] , 2 [email protected] , 3 [email protected] ABSTRACT This research aimed to: (1) describe the need of Javanese poetry textbook (tembang and guritan) by linguistic lecturer and education linguistic program students (2) compile the prototype of Javanese Poetry textbook with using sociology of Literature approach; (3) develop the prototype of Tembang and Modern Javanese Poetry textbook becomes textbook; (4) determine textbook effectiveness which has been developed through experimentation. This study is very important to know the response of the users, caregivers, teachers / lecturers and students Javanese poetry, both traditional (songs) and modern (guritan). In addition, the study sought to understand the desires and the actual state of preservation and development of the literary heritage of the ancestors, the song and guritan. In fact, modern Javanese poetry (guritan) still thrive today Keywords: Tembang, Guritan, Jawa, Poetry, Linguistic INTRODUCTION Literature and Javanese Culture Learning are integrated in one subject matter in the second semester of Indonesian study program, Teacher Training of Education Faculty (FKIP) UNS and in S2 Javanese study program which dissociated and passed to the first semester (Syllabus FKIP and PPS, 2011).The lecturing is given in S1 program since the implementing of National Curriculum 1995 FKIP and since the forming of S2 Javanese Study Program, PPS UNS (2008). -

My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics Of

MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance David A. McDonald Duke University Press ✹ Durham and London ✹ 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data McDonald, David A., 1976– My voice is my weapon : music, nationalism, and the poetics of Palestinian resistance / David A. McDonald. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5468-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5479-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Palestinian Arabs—Music—History and criticism. 2. Music—Political aspects—Israel. 3. Music—Political aspects—Gaza Strip. 4. Music—Political aspects—West Bank. i. Title. ml3754.5.m33 2013 780.89′9274—dc23 2013012813 For Seamus Patrick McDonald Illustrations viii Note on Transliterations xi Note on Accessing Performance Videos xiii Acknowledgments xvii introduction ✹ 1 chapter 1. Nationalism, Belonging, and the Performativity of Resistance ✹ 17 chapter 2. Poets, Singers, and Songs ✹ 34 Voices in the Resistance Movement (1917–1967) chapter 3. Al- Naksa and the Emergence of Political Song (1967–1987) ✹ 78 chapter 4. The First Intifada and the Generation of Stones (1987–2000) ✹ 116 chapter 5. Revivals and New Arrivals ✹ 144 The al- Aqsa Intifada (2000–2010) CONTENTS chapter 6. “My Songs Can Reach the Whole Nation” ✹ 163 Baladna and Protest Song in Jordan chapter 7. Imprisonment and Exile ✹ 199 Negotiating Power and Resistance in Palestinian Protest Song chapter 8. -

Discovering the 'Language' and the 'Literature' of West Java

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 34, No.1, June 1996 Discovering the 'Language' and the 'Literature' of West Java: An Introduction to the Formation of Sundanese Writing in 19th Century West Java* Mikihira MaRlYAMA** I The 'Language' Discovering the 'Language' An ethnicity (een volk) is defined by a language.i) This idea had come to be generally accepted in the Dutch East Indies at the beginning of the twentieth century. The prominent Sundanese scholar, Raden Memed Sastrahadiprawira, expressed it, probably in the 1920s, as follows: Basa teh anoe djadi loeloegoe, pangtetelana djeung pangdjembarna tina sagala tanda-tanda noe ngabedakeun bangsa pada bangsa. Lamoen sipatna roepa-roepa basa tea leungit, bedana bakat-bakatna kabangsaan oge moesna. Lamoen ras kabangsaanana soewoeng, basana eta bangsa tea oge lila-lila leungit. [Sastrahadiprawira in Deenik n. y.: 2] [The language forms a norm: the most evident and the most comprehensive symbols (notions) to distinguish one ethnic group from another. If the characteristics of a language disappear, the distinguishing features of an ethnicity will fade away as well. If an ethnicity no longer exists, the language of the ethnic group will also disappear in due course of time.] There is a third element involved: culture. Here too, Dutch assumptions exerted a great influence upon the thinking of the growing group of Sundanese intellectuals: a It occurred to me that I wanted to be a scholar when I first met the late Prof. Kenji Tsuchiya in 1980. It is he who stimulated me to write about the formation of Sundano logy in a letter from Jakarta in 1985. -

Cahiers D'ethnomusicologie, 7

Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie Anciennement Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 7 | 1994 Esthétiques Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/1279 ISSN : 2235-7688 Éditeur ADEM - Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie Édition imprimée Date de publication : 31 décembre 1994 ISBN : 2-8257-0503-9 ISSN : 1662-372X Référence électronique Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie, 7 | 1994, « Esthétiques » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 09 décembre 2011, consulté le 06 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/1279 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 6 mai 2019. Tous droits réservés 1 Si nous avons l’habitude d’envisager le champ de l’esthétique à la lumière de notre sensibilité et de nos goûts personnels, nous constatons qu’en d’autres temps et en d’autres lieux, il est surtout affaire de conformité, et que l’éventuelle originalité d’un artiste, d’un artisan ou d’un musicien n’y est jugée pertinente que dans la mesure où elle s’inscrit dans les limites assignées par la tradition à la créativité individuelle. Dans le contexte de nombreuses civilisations, de la même façon qu’en Europe au Moyen Age, le terme d’art définit essentiellement un savoir-faire ; la raison d’être des formes qu’il met en œuvre, notamment des formes musicales, procède avant tout de leur efficacité reconnue, tant sur le plan de leur valeur symbolique et de l’usage rituel qui en découle, qu’au niveau des vertus que sa pratique engendre et, accessoirement, à celui des émotions et des réactions qu’elle suscite chez ses destinataires. L’esthétique peut être définie comme la « science du beau culturellement déterminé », et en même temps comme le « pouvoir attractif de la beauté » ; elle se réfère ainsi aux domaines de la métaphysique (dont elle tire ses modèles), de la philosophie (qui en définit les principes), de l’anthropologie culturelle (qui en analyse les champs d’application collectif) et de la psychologie (qui en mesure les effets individuels). -

Sanggit and Soeharto Power Discourse in Purwa Leather Puppets Rama Tambak Play

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 280 International Seminar On Recent Language, Literature, And Local Culture Studies (BASA 2018) Sanggit and Soeharto Power Discourse in Purwa Leather Puppets Rama Tambak Play Darmoko Faculty of Humanities Universitas Indonesia Depok, West Java, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract --- Purwa Leather Puppets (Hereinafter abbreviated as PLP) from time to time are used by the power as a media of political propaganda. The symbols in PLP are used by the authorities of power to influence the community to follow the values that have been designed in a PLP performances. When Soeharto came to power, the discourse of power was reflected and intertwined in the performance. The performance of PLP play Rama Tambak (Hereinafter abbreviated as RT), was inseparable from the discourse of Soeharto's power. In February 1998 the play was performed in various cities in Java to stem the distress that befell the Indonesian nation. The problem in this paper can be formulated, how does the discourse of Soeharto's power operate and intertwine in the RT play? To answer these problems the concept of the discourse of power - the knowledge of Foucault and the Idea of Power in Javanese Culture from Benedict Anderson, as well as the implementation of qualitative methodology. The PLP performance RT play by Ki Manteb Soedarsono at Taman Mini Indonesia Indah Jakarta on February 13, 1998 was used as the study data. This paper assumes that the discourse of power operates and interwoven in the PLP to influence the community so that they can participate in stopping national disasters. -

Gamelan Cudamani Study Guide 1011.Indd

2010–2011 SEASON SchoolTime Study Guide Gamelan Çudamani Friday, October 22, 2010 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime Your class will att end The “Bamboo to Bronze” performance of Gamelan Çudamani on Friday, October 22 at 11 am. The dazzing Gamelan Çudamani (pronounced SOOD-ah-mân-ee) off ers an opportunity to witness the splendor and creati ve life-force of music and dance in Bali. Twenty-four of Bali’s fi nest arti sts parti cipate in this new producti on, a potent synthesis of sound, moti on, and visual images, celebrati ng Balinese culture and everyday life. Using This Study Guide You can use these materials to engage your students and enrich their Cal Performances fi eld trip. Before att ending the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student Resource Sheet on pages 2 & 3 and give it to your students several days before the show. • Discuss the informati on on pages 4-7 About the Performance & Arti sts with your students. • Read to your students from About the Art Form on page 8, About Bali on page 10 and Religion in Bali on page 13. • Engage your students in two or more acti viti es on pages 15-17. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding questi ons, found on pages 2,4,8,10 & 13. • Immerse students further into the subject matt er and art form by using the Resource and Glossary secti ons on pages 17 & 18. At the performance: Your class can acti vely parti cipate during the performance by: • Listening carefully for the musical cycles, melodies and rhythms • Observing how the dancers tell a story and express ideas and emoti ons through their movements • Thinking about how dance and music express Balinese culture and history • Marveling at the skill of the musicians and dancers • Refl ecti ng on the sounds, sights, and performance skills you experience at the theater We look forward to seeing you at SchoolTime! SchoolTime Circus Oz | Table of Contents 1. -

CHAIRIL ANWAR: the POET and Hls LANGUAGE

VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 63 CHAIRIL ANWAR: THE POET AND HlS LANGUAGE BOBN S. OBMARJATI THB HAGUB - MARTINUS NIJHOFF 1972 CHAIRIL ANWAR So here I am, in the middle way, having had twenty years - Twenty years largely wasted, the years of l'entTe deux guerres - Trying to leam to use words, and every attempt Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure Because one has only learnt to get the better of words For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate With shabby equipment always deteriorating In the genera! mess of imprecision of feeling, Undisciplined squads of emotion ............................. (T. S. Eliot, East CokeT V) To my parents as a partial instalment in return for their devotion To 'MB' with love and in gratitude for sharing serenity and true friendship with me VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 63 CHAIRIL ANWAR: THE POET AND HlS LANGUAGE BOEN S. OEMARJATI THE HAGUE - MARTINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1508.3 T ABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VII PREF ACE IX INTRODUCTION . XIII 1. The Japanese Occupation: The Break with the Past XIII 2. The Situation respecting the Indonesian Language . XIV 3. The Situ at ion in respect of Indonesian Literature XVI 4. Biographical Data . XX LIST OF ABBREVIA TIONS AND SYMBOLS . XXVII CHAPTER I: LANGUAGE AND POE TRY 1. -

Karel Čapek's Travels

KARELČAPEK’STRAVELS:ADVENTURESOFA NEWVISION by MirnaŠolić Athesissubmittedinconformitywiththerequirements forthedegreeofDoctorofPhilosophy DepartmentofSlavicLanguagesandLiteratures UniversityofToronto ©CopyrightbyMirnaŠolić (2008) Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58091-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58091-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author’s permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformément à la loi canadienne sur la Privacy Act some supporting forms protection de la vie privée, quelques may have been removed from this formulaires secondaires ont été enlevés de thesis. -

Javanese Wayang Kulit, Shadow-Puppet Theater of Indonesia

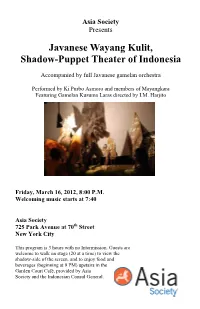

Asia Society Presents Javanese Wayang Kulit, Shadow-Puppet Theater of Indonesia Accompanied by full Javanese gamelan orchestra Performed by Ki Purbo Asmoro and members of Mayangkara Featuring Gamelan Kusuma Laras directed by I.M. Harjito Friday, March 16, 2012, 8:00 P.M. Welcoming music starts at 7:40 Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City This program is 3 hours with no Intermission. Guests are welcome to walk on stage (20 at a time) to view the shadow-side of the screen, and to enjoy food and beverages (beginning at 9 PM) upstairs in the Garden Court Café, provided by Asia Society and the Indonesian Consul General. Wayang Kulit Performance, Featuring Ki Purbo Asmoro and Mayangkara Déwa Ruci: Bima’s Spiritual Enlightenment Gamelan Kusuma Laras: Mayangkara: I.M. Harjito, Artistic Director Wakidi Dwidjomartono, musical Anne Stebinger, Co-Director director Glenn Baun-Cueto Yayuk Sri Rahayu Wayne Forrest (guest artist) Gatot Saminto Stuart Frankel Timbul Saminto Barry Frier Minarto Joseph Getter (guest artist) Sapto David Haiman Kasino Seán Hanson Subandi Denni Harjito Wiji Santoso Uci Haryono Rex Isenberg Ronald Kienhuis Robin Kimball Lutfi Kurniawan Bleakley McDowell Puspitaningsih Moeis Debie Morris Emily Jane O'Dell Dan Owen Eva Peck Mark Reilly Jason Robira Leslie Rudden Dave Ruder Jenny Sakirman Carla Scheele Amy Scott Don Shewey Elly Siswanto Tatung Suharjono Sri Suharti Bambang Sunarno Safiah Satiman Taylor Carole Weber Dylan Widjiono Antonius Wiriadjaja Sri Zainuddin Tonight’s Story: Déwa Ruci (Bima’s Spiritual Enlightenment) This episode focuses on Bima, the second of the five Pandhawa brothers. Bima is disturbed by a number of recent events in his family and has de- cided that he needs to strengthen his spiritual side and take some time to be introspective about his life. -

Downloaded From

H. Creese Old Javanese studies; A review of the field In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Old Javanese texts and culture 157 (2001), no: 1, Leiden, 3-33 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 04:40:52AM via free access HELEN CREESE Old Javanese Studies A Review of the Field For nearly two hundred years the academic study of the languages and liter- atures of ancient Java has attracted the attention of scholars. Interest in Old Javanese had its genesis in the Orientalist traditions of early nineteenth-cen- tury European scholarship. Until the end of the colonial period, the study of Old Javanese was dominated by Dutch scholars whose main interest was philology. Not surprisingly, the number of researchers working in this field has never been large, but as the field has expanded from its original philo- logical focus to encompass research in a variety of disciplines, it has remain1 ed a small but viable research area in the wider field of Indonesian studies. As a number of recent review articles have shown (Andaya and Andaya 1995; Aung-Thwin 1995; McVey 1995; Reynolds 1995), in the field of South- east Asian studies as a whole, issues of modern state formation and devel- opment have dominated the interest of scholars and commentators. Within this academic framework, interest in the Indonesian archipelago in the period since independence has also focused largely on issues relating to the modern Indonesian state; This focus on national concerns has not lent itself well to a .rich ongoing scholarship on regional cultures, whether ancient or modern. -

The Function of Poetry in the Maqamat Al-Hariri

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2-24-2020 The Function of Poetry in the Maqamat al-Hariri Hussam Almujalli Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Arabic Language and Literature Commons, Arabic Studies Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Almujalli, Hussam, "The Function of Poetry in the Maqamat al-Hariri" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5156. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5156 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE FUNCTION OF POETRY IN THE MAQAMAT AL-HARIRI A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Humanities and Social Sciences College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Comparative Literature by Hussam Almujalli B.A., Al-Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, 2006 M.A., Brandeis University, 2014 May 2020 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge all of the help that the faculty members of the Comparative Literature Department at Louisiana State University have given me during my time there. I am particularly grateful to my advisor, Professor Gregory Stone, and to my committee members, Professor Mark Wagner and Professor Touria Khannous, for their constant help and guidance. This dissertation would not have been possible without the funding support of the Comparative Literature Department at Louisiana State University.