Karel Čapek's Travels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE JAVANESE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMED IN THE CLASSIC PALACE STYLE: AN ANALYSIS OF RAMA’S CROWN AS TOLD BY KI PURBO ASMORO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By GUAN YU, LAM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 JAVANESE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMED IN THE CLASSIC PALACE STYLE: AN ANALYSIS OF RAMA’S CROWN AS TOLD BY KI PURBO ASMORO A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Paula Conlon, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ______________________________ Dr. Marvin Lamb © Copyright by GUAN YU, LAM 2016 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would like to take this opportunity to thank the members of my committee: Dr. Paula Conlon, Dr. Eugene Enrico, and Dr. Marvin Lamb for their guidance and suggestions in the preparation of this thesis. I would especially like to thank Dr. Paula Conlon, who served as chair of the committee, for the many hours of reading, editing, and encouragement. I would also like to thank Wong Fei Yang, Thow Xin Wei, and Agustinus Handi for selflessly sharing their knowledge and helping to guide me as I prepared this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their continued support throughout this process. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................... -

Sociology of Literature Approach

ISSN: 2186-8492, ISSN: 2186-8484 Print Vol. 2 No. 3 August 2013 ASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN JAVANESE POETRY AND JAVANESE TEMBANG FOR THE LINGUISTIC EDUCATION PROGRAM: SOCIOLOGY OF LITERATURE APPROACH Herman J. Waluyo 1, Sahid Teguh Widodo 2, Y. Slamet 3 Universitas Sebelas Maret, Solo, INDONESIA. 1 [email protected] , 2 [email protected] , 3 [email protected] ABSTRACT This research aimed to: (1) describe the need of Javanese poetry textbook (tembang and guritan) by linguistic lecturer and education linguistic program students (2) compile the prototype of Javanese Poetry textbook with using sociology of Literature approach; (3) develop the prototype of Tembang and Modern Javanese Poetry textbook becomes textbook; (4) determine textbook effectiveness which has been developed through experimentation. This study is very important to know the response of the users, caregivers, teachers / lecturers and students Javanese poetry, both traditional (songs) and modern (guritan). In addition, the study sought to understand the desires and the actual state of preservation and development of the literary heritage of the ancestors, the song and guritan. In fact, modern Javanese poetry (guritan) still thrive today Keywords: Tembang, Guritan, Jawa, Poetry, Linguistic INTRODUCTION Literature and Javanese Culture Learning are integrated in one subject matter in the second semester of Indonesian study program, Teacher Training of Education Faculty (FKIP) UNS and in S2 Javanese study program which dissociated and passed to the first semester (Syllabus FKIP and PPS, 2011).The lecturing is given in S1 program since the implementing of National Curriculum 1995 FKIP and since the forming of S2 Javanese Study Program, PPS UNS (2008). -

Discovering the 'Language' and the 'Literature' of West Java

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 34, No.1, June 1996 Discovering the 'Language' and the 'Literature' of West Java: An Introduction to the Formation of Sundanese Writing in 19th Century West Java* Mikihira MaRlYAMA** I The 'Language' Discovering the 'Language' An ethnicity (een volk) is defined by a language.i) This idea had come to be generally accepted in the Dutch East Indies at the beginning of the twentieth century. The prominent Sundanese scholar, Raden Memed Sastrahadiprawira, expressed it, probably in the 1920s, as follows: Basa teh anoe djadi loeloegoe, pangtetelana djeung pangdjembarna tina sagala tanda-tanda noe ngabedakeun bangsa pada bangsa. Lamoen sipatna roepa-roepa basa tea leungit, bedana bakat-bakatna kabangsaan oge moesna. Lamoen ras kabangsaanana soewoeng, basana eta bangsa tea oge lila-lila leungit. [Sastrahadiprawira in Deenik n. y.: 2] [The language forms a norm: the most evident and the most comprehensive symbols (notions) to distinguish one ethnic group from another. If the characteristics of a language disappear, the distinguishing features of an ethnicity will fade away as well. If an ethnicity no longer exists, the language of the ethnic group will also disappear in due course of time.] There is a third element involved: culture. Here too, Dutch assumptions exerted a great influence upon the thinking of the growing group of Sundanese intellectuals: a It occurred to me that I wanted to be a scholar when I first met the late Prof. Kenji Tsuchiya in 1980. It is he who stimulated me to write about the formation of Sundano logy in a letter from Jakarta in 1985. -

Cahiers D'ethnomusicologie, 7

Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie Anciennement Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 7 | 1994 Esthétiques Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/1279 ISSN : 2235-7688 Éditeur ADEM - Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie Édition imprimée Date de publication : 31 décembre 1994 ISBN : 2-8257-0503-9 ISSN : 1662-372X Référence électronique Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie, 7 | 1994, « Esthétiques » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 09 décembre 2011, consulté le 06 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/1279 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 6 mai 2019. Tous droits réservés 1 Si nous avons l’habitude d’envisager le champ de l’esthétique à la lumière de notre sensibilité et de nos goûts personnels, nous constatons qu’en d’autres temps et en d’autres lieux, il est surtout affaire de conformité, et que l’éventuelle originalité d’un artiste, d’un artisan ou d’un musicien n’y est jugée pertinente que dans la mesure où elle s’inscrit dans les limites assignées par la tradition à la créativité individuelle. Dans le contexte de nombreuses civilisations, de la même façon qu’en Europe au Moyen Age, le terme d’art définit essentiellement un savoir-faire ; la raison d’être des formes qu’il met en œuvre, notamment des formes musicales, procède avant tout de leur efficacité reconnue, tant sur le plan de leur valeur symbolique et de l’usage rituel qui en découle, qu’au niveau des vertus que sa pratique engendre et, accessoirement, à celui des émotions et des réactions qu’elle suscite chez ses destinataires. L’esthétique peut être définie comme la « science du beau culturellement déterminé », et en même temps comme le « pouvoir attractif de la beauté » ; elle se réfère ainsi aux domaines de la métaphysique (dont elle tire ses modèles), de la philosophie (qui en définit les principes), de l’anthropologie culturelle (qui en analyse les champs d’application collectif) et de la psychologie (qui en mesure les effets individuels). -

Sanggit and Soeharto Power Discourse in Purwa Leather Puppets Rama Tambak Play

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 280 International Seminar On Recent Language, Literature, And Local Culture Studies (BASA 2018) Sanggit and Soeharto Power Discourse in Purwa Leather Puppets Rama Tambak Play Darmoko Faculty of Humanities Universitas Indonesia Depok, West Java, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract --- Purwa Leather Puppets (Hereinafter abbreviated as PLP) from time to time are used by the power as a media of political propaganda. The symbols in PLP are used by the authorities of power to influence the community to follow the values that have been designed in a PLP performances. When Soeharto came to power, the discourse of power was reflected and intertwined in the performance. The performance of PLP play Rama Tambak (Hereinafter abbreviated as RT), was inseparable from the discourse of Soeharto's power. In February 1998 the play was performed in various cities in Java to stem the distress that befell the Indonesian nation. The problem in this paper can be formulated, how does the discourse of Soeharto's power operate and intertwine in the RT play? To answer these problems the concept of the discourse of power - the knowledge of Foucault and the Idea of Power in Javanese Culture from Benedict Anderson, as well as the implementation of qualitative methodology. The PLP performance RT play by Ki Manteb Soedarsono at Taman Mini Indonesia Indah Jakarta on February 13, 1998 was used as the study data. This paper assumes that the discourse of power operates and interwoven in the PLP to influence the community so that they can participate in stopping national disasters. -

Gamelan Cudamani Study Guide 1011.Indd

2010–2011 SEASON SchoolTime Study Guide Gamelan Çudamani Friday, October 22, 2010 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime Your class will att end The “Bamboo to Bronze” performance of Gamelan Çudamani on Friday, October 22 at 11 am. The dazzing Gamelan Çudamani (pronounced SOOD-ah-mân-ee) off ers an opportunity to witness the splendor and creati ve life-force of music and dance in Bali. Twenty-four of Bali’s fi nest arti sts parti cipate in this new producti on, a potent synthesis of sound, moti on, and visual images, celebrati ng Balinese culture and everyday life. Using This Study Guide You can use these materials to engage your students and enrich their Cal Performances fi eld trip. Before att ending the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student Resource Sheet on pages 2 & 3 and give it to your students several days before the show. • Discuss the informati on on pages 4-7 About the Performance & Arti sts with your students. • Read to your students from About the Art Form on page 8, About Bali on page 10 and Religion in Bali on page 13. • Engage your students in two or more acti viti es on pages 15-17. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding questi ons, found on pages 2,4,8,10 & 13. • Immerse students further into the subject matt er and art form by using the Resource and Glossary secti ons on pages 17 & 18. At the performance: Your class can acti vely parti cipate during the performance by: • Listening carefully for the musical cycles, melodies and rhythms • Observing how the dancers tell a story and express ideas and emoti ons through their movements • Thinking about how dance and music express Balinese culture and history • Marveling at the skill of the musicians and dancers • Refl ecti ng on the sounds, sights, and performance skills you experience at the theater We look forward to seeing you at SchoolTime! SchoolTime Circus Oz | Table of Contents 1. -

CHAIRIL ANWAR: the POET and Hls LANGUAGE

VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 63 CHAIRIL ANWAR: THE POET AND HlS LANGUAGE BOBN S. OBMARJATI THB HAGUB - MARTINUS NIJHOFF 1972 CHAIRIL ANWAR So here I am, in the middle way, having had twenty years - Twenty years largely wasted, the years of l'entTe deux guerres - Trying to leam to use words, and every attempt Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure Because one has only learnt to get the better of words For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate With shabby equipment always deteriorating In the genera! mess of imprecision of feeling, Undisciplined squads of emotion ............................. (T. S. Eliot, East CokeT V) To my parents as a partial instalment in return for their devotion To 'MB' with love and in gratitude for sharing serenity and true friendship with me VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 63 CHAIRIL ANWAR: THE POET AND HlS LANGUAGE BOEN S. OEMARJATI THE HAGUE - MARTINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1508.3 T ABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VII PREF ACE IX INTRODUCTION . XIII 1. The Japanese Occupation: The Break with the Past XIII 2. The Situation respecting the Indonesian Language . XIV 3. The Situ at ion in respect of Indonesian Literature XVI 4. Biographical Data . XX LIST OF ABBREVIA TIONS AND SYMBOLS . XXVII CHAPTER I: LANGUAGE AND POE TRY 1. -

Javanese Wayang Kulit, Shadow-Puppet Theater of Indonesia

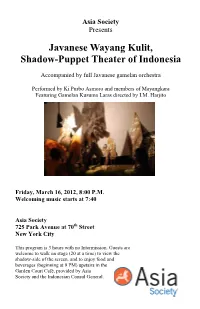

Asia Society Presents Javanese Wayang Kulit, Shadow-Puppet Theater of Indonesia Accompanied by full Javanese gamelan orchestra Performed by Ki Purbo Asmoro and members of Mayangkara Featuring Gamelan Kusuma Laras directed by I.M. Harjito Friday, March 16, 2012, 8:00 P.M. Welcoming music starts at 7:40 Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City This program is 3 hours with no Intermission. Guests are welcome to walk on stage (20 at a time) to view the shadow-side of the screen, and to enjoy food and beverages (beginning at 9 PM) upstairs in the Garden Court Café, provided by Asia Society and the Indonesian Consul General. Wayang Kulit Performance, Featuring Ki Purbo Asmoro and Mayangkara Déwa Ruci: Bima’s Spiritual Enlightenment Gamelan Kusuma Laras: Mayangkara: I.M. Harjito, Artistic Director Wakidi Dwidjomartono, musical Anne Stebinger, Co-Director director Glenn Baun-Cueto Yayuk Sri Rahayu Wayne Forrest (guest artist) Gatot Saminto Stuart Frankel Timbul Saminto Barry Frier Minarto Joseph Getter (guest artist) Sapto David Haiman Kasino Seán Hanson Subandi Denni Harjito Wiji Santoso Uci Haryono Rex Isenberg Ronald Kienhuis Robin Kimball Lutfi Kurniawan Bleakley McDowell Puspitaningsih Moeis Debie Morris Emily Jane O'Dell Dan Owen Eva Peck Mark Reilly Jason Robira Leslie Rudden Dave Ruder Jenny Sakirman Carla Scheele Amy Scott Don Shewey Elly Siswanto Tatung Suharjono Sri Suharti Bambang Sunarno Safiah Satiman Taylor Carole Weber Dylan Widjiono Antonius Wiriadjaja Sri Zainuddin Tonight’s Story: Déwa Ruci (Bima’s Spiritual Enlightenment) This episode focuses on Bima, the second of the five Pandhawa brothers. Bima is disturbed by a number of recent events in his family and has de- cided that he needs to strengthen his spiritual side and take some time to be introspective about his life. -

Downloaded From

H. Creese Old Javanese studies; A review of the field In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Old Javanese texts and culture 157 (2001), no: 1, Leiden, 3-33 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 04:40:52AM via free access HELEN CREESE Old Javanese Studies A Review of the Field For nearly two hundred years the academic study of the languages and liter- atures of ancient Java has attracted the attention of scholars. Interest in Old Javanese had its genesis in the Orientalist traditions of early nineteenth-cen- tury European scholarship. Until the end of the colonial period, the study of Old Javanese was dominated by Dutch scholars whose main interest was philology. Not surprisingly, the number of researchers working in this field has never been large, but as the field has expanded from its original philo- logical focus to encompass research in a variety of disciplines, it has remain1 ed a small but viable research area in the wider field of Indonesian studies. As a number of recent review articles have shown (Andaya and Andaya 1995; Aung-Thwin 1995; McVey 1995; Reynolds 1995), in the field of South- east Asian studies as a whole, issues of modern state formation and devel- opment have dominated the interest of scholars and commentators. Within this academic framework, interest in the Indonesian archipelago in the period since independence has also focused largely on issues relating to the modern Indonesian state; This focus on national concerns has not lent itself well to a .rich ongoing scholarship on regional cultures, whether ancient or modern. -

Music As Episteme, Text, Sign & Tool: Comparative Approaches To

I would like to dedicate this work firstly to Sue Achimovich, my mother, without whose constant support I wouldn’t have been able to have jumped across the abyss and onto the path; I would also like to dedicate the work to Dr Saskia Kersenboom who gave me the light and showed me the way; Finally I would like to dedicate the work to both Patrick Eecloo and Guy De Mey who supported me when I could have fallen over the edge … This edition is also dedicated to Jaak Van Schoor who supported me throughout the creative process of this work. Foreword This work has been produced thanks to more than four years of work. The first years involved a great deal of self- questioning; moving from being an active creative artist—a composer and performer of experimental music- theatre—to being a theoretician has been a long journey. Suffice to say, on the gradual process which led to the ‘composition’ of this work, I went through many stages of looking back at my own creative work to discover that I had already begun to answer many of the questions posed by my new research into Balinese culture, communicating remarkable information about myself and the way I’ve attempted to confront my world in a physically embodied fashion. My early academic experiments, attending conferences and writing papers, involved at first largely my own compositional work. What I realise now is that I was on a journey towards developing a system of analysis which would be based on both artistic and scientific information, where ‘subjective’ experience would form an equally valid ‘product’ for analysis: it is, after all, only through our own personal experience that we can interface with the world. -

A New Reading in Javanese Traditional Poetry

The Unity of Culture: A New Reading in Javanese Traditional Poetry Nur Ahmad1, Akhmad Arif Junaidi2 Universitas Islam Negeri Walisongo Semarang1,2 {[email protected], [email protected]} Abstract. This paper argues for the existence and demonstrates the way of composing macapat in Javanese Islamic tradition. It examines several not fully explored texts in several early modern Javanese manuscripts written by pesantren agents. To examine those manuscripts which were written roughly in the range from 1700-1900, the research starts with philological study. Then, it employs the framework proposed by Davaney [1] in analyzing the dynamic process of culture. In conclusion, the paper shows that not only does macapat exist in pesantren, the Islamic traditional education body has also played an important role on the dissemination of the traditional song especially for transmission of religious teachings. The research also discovers that the agency of pesantren actors to popularize Arabic kitabs and to ease the process of study those books leads to the rendering Arabic kitabs into macapat in Javanese. Thus, this paper shows that the pesantren tradition is part of the formation of what is called “Javanese culture”. Keywords: Culture; Tembang Macapat; Pesantren Tradition; Javanese Literature; Islamic Manuscript 1 Introduction The popularity of macapat in the Javanese society cannot be more emphasized. Geertz [2, p. 282] visualized that in the rural areas, “You cannot walk from one end of Modjokuto to the other after ten at night and not hear someone singing a tembang somewhere along the way”. Ronggasasmita in [3, pp. 1–2] provided an account on texts usually read by elites of the palace. -

Book of Abstracts Sponsors

sociolinguistics symposium micro and macro connections 3+4+5 April 2008 Amsterdam – Papers – Posters – Themed panels and Workshops Book of Abstracts Sponsors www.meertens.knaw.nl/ss17 ABSTRACTS Sociolinguistics Symposium 17 Amsterdam 3-5 April 2008 3 SS17: MICRO AND MACRO CONNECTION S The 17th edition of 'The Sociolinguistic Symposium', Europe's leading international conference on language in society, will be held in Amsterdam from 3-5 April 2008. The chairing Institute is The Meertens Institute (Department of Language Variation). The theme of this conference is Micro and Macro Connections. The conference will be held at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU). Sociolinguistics is about the relationship between language and society. By proposing Micro and Macro connec- tions as the conference's theme, we want to invite researchers who generate insights into the interplay between language and society by examining the ways social structure is oriented to and affected by verbal practices. Language does not just reflect social facts. The connections between language and social organization are multi- layered, dynamic and reflexive and they are accomplished at many different levels of language use. When people use language, they are actors engaging in some interactional project that defines the ground for the ways param- eters such as identity, community and culture are shaped. Therefore, we have welcomed in particular proposals that explore the ways verbal practices display and contribute to social organization. About the Sociolinguistics Symposia The Sociolinguistics Symposia are organized bi-annually since the 1970s by a group of sociolinguists who rec- ognized the need for a forum for discussing research findings and for debating theoretical and methodological issues concerning language in society.