Tara and Q'iwa—Worlds of Sound and Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Traditions in the Postconquest World

This is an extract from: Native Traditions in the Postconquest World Elizabeth Hill Boone and Tom Cummins, Editors Published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 1998 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html A Nation Surrounded A Nation Surrounded BRUCE MANNHEIM THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Poetry is the plow tearing open and turning over time, so that the deep layers of time, its black under-soil, end up on the surface. Osip Mandelstam (1971: 50) N The Language of the Inka since the European Invasion (1991), I argued that the descendants of the Inkas, modern Southern Peruvian Quechua speak- Iers, are “a nation surrounded,” to use a phrase from the Peruvian novelist José María Arguedas (1968: 296), in two senses: first and more obviously, South- ern Peruvian Quechuas live in an institutional world mediated by the language of their conquerors, Spanish. The conquistadores brought along not only priests and interpreters but a public notary whose job it was to record the legal proto- cols of conquest. From that moment on, native Andeans became the objects of encompassing discourses that have not only shaped colonial and national poli- cies toward the native peoples but, in the legal and commercial arenas, also determined the fates of individual households and communities. For example, the judicial proceedings through which native lands passed into the possession of Spanish colonists were held in Spanish, and the archives are rife with cases in which even the notices of the proceedings were served on native Andean com- munities in Spanish. -

Aymara UNIDAD DE COORDINACIÓN DE ASUNTOS INDÍGENAS DEL MINISTERIO DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL Y FAMILIA

Diccionario de la lengua Aymara UNIDAD DE COORDINACIÓN DE ASUNTOS INDÍGENAS DEL MINISTERIO DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL Y FAMILIA Ana Millanao Contreras ASESORA ESPECIAL PARA ASUNTOS INDÍGENAS Francisco Ule Rebolledo COORDINADOR UNIDAD ASUNTOS INDÍGENAS Natalie Castro López Lucy Barriga Cortés COORDINACIÓN GENERAL Andrés García Flores TRADUCCIÓN Rodrigo Olavarría Lavín INVESTIGACIÓN Y EDICIÓN GENERAL Carolina Zañartu Salas Juan Américo Pastene de la Jara Lilian Ferrada Sepúlveda INVESTIGACIÓN, DISEÑO Y DIAGRAMACIÓN Especial agradecimiento a la Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena por su colaboración en la referencia de traductores y revisión. Diccionario de la lengua Aymara Tras varios de meses de trabajo, junto al equipo de la Unidad de Coordinación de Asuntos Indígenas del Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, hemos finalizado el desarrollo de una herramienta, que consideramos de gran importancia para promover las lenguas de los pueblos indígenas de Chile, ya que como Gobierno estamos poniendo especial énfasis en fortalecer y concientizar a la población respecto a su revitalización. Cada uno de los diccionarios —elaborados en lengua aymara, quechua, mapuche y rapa nui— contempla una primera parte con antecedentes de estos pueblos, información sobre la cultura y la cosmovisión, además de datos para comprender aspectos lingüísticos. La segunda parte consta de palabras y su respectiva traducción, divididas por unidades para facilitar el aprendizaje, mediante la asociación. También fueron incluidas frases de uso cotidiano para acercar más la lengua a quienes se interesen en aprender. Invitamos a revitalizar las lenguas indígenas, como parte del merecido reconocimiento a los pueblos indígenas del país. Por otro lado, reafirmamos el compromiso de seguir desarrollando espacios de documentación de las lenguas para mantener vivos estos verdaderos tesoros, que son parte de nuestra identidad. -

Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor

Silva Collins, Gabriel 2019 Anthropology Thesis Title: Making the Mountains: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor: Antonia Foias Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: No Contains Copyrighted Material: No MAKING THE MOUNTAINS: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads by GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS Antonia Foias, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Anthropology WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 19, 2019 Introduction Peru is famous for its Pre-Hispanic archaeological sites: places like Machu Picchu, the Nazca lines, and the city of Chan Chan. Ranging from the earliest cities in the Americas to Inca metropolises, millennia of urban human history along the Andes have left large and striking sites scattered across the country. But cities and monuments do not exist in solitude. Peru’s ancient sites are connected by a vast circulatory system of roads that connected every corner of the country, and thousands of square miles beyond its current borders. The Inca road system, or Qhapaq Ñan, is particularly famous; thousands of miles of trails linked the empire from modern- day Colombia to central Chile, crossing some of the world’s tallest mountain ranges and driest deserts. The Inca state recognized the importance of its road system, and dotted the trails with rest stops, granaries, and religious shrines. Inca roads even served directly religious purposes in pilgrimages and a system of ritual pathways that divided the empire (Ogburn 2010). This project contributes to scholarly knowledge about the Inca and Pre-Hispanic Andean civilizations by studying the roads which stitched together the Inca state. -

La Cosmología En El Dibujo Del Altar Del Quri Kancha Según Don Joan

La cosmología en el dibujo del altar del Quri Kancha según don Joan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salca Maygua Rita Fink Se suele adscribir al dibujo del altar de Quri Kancha una estructura bipartita (dos campos separados por un eje vertical), la cual refleja la oposición andina de hanan-hurin o alternativamente la simetría de los altares eclesiásticos. El presente trabajo identifica los elementos del dibujo y analiza las parejas que ellos componen, examinando el simbolismo de cada una de ellas y las interrelaciones de sus componentes en varias fuentes de los siglos XVI-XX. El mundo dibujado está organizado según el principio andino de hanan-hurin aplicado en dos dimensiones, la horizontal y la vertical. Dos ejes, hanan y hurin, dividen el espacio en cuatro campos distintos. Los campos inferiores están organizados de manera inversa con respecto al espacio superior. Semejantes estructuras cuatripartitas se encuentran en otras representaciones espacio-temporales andinas. The structure of the drawing of the Quri Kancha altar has been described as dual, reflecting either the Andean hanan-hurin complementarity or the symmetry of Christian church altars. Present study identifies the elements presented in the drawing and analyses the couples which they comprise, demonstrating the symbolism of each couple and the hanan-hurin relations within them, as evident in XVI-XX century sources. The world presented in the drawing of the Quri Kancha altar is organized according to the Andean hanan-hurin principle applied on two-dimensional scale (horizontal and vertical). Two axes - hanan and hurin - divide the space into 4 distinct fields. The lower fields are inverted relative to the hanan space above. -

ATTRACTING and BANNING ANKARI: Musical and Climate

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lund University Publications - Student Papers ATTRACTING AND BANNING ANKARI: Musical and Climate Change in the Kallawaya Region in Northern Bolivia Degree of Master of Science (Two Years) in Human Ecology: Culture, Power and Sustainability 30 ECTS CPS: International Master’s Programme in Human Ecology Human Ecology Division Department of Human Geography Faculty of Social Sciences Lund University by Sebastian Hachmeyer Department: Department of Human Geography Human Ecology Division Address: Geocentrum Sölvegatan 10 223 62 Lund Telephone: 046-222 17 59 Supervisor: Dr. Anders Burman Dr. Bernardo Rozo Lopez Department of Human Geography Department of Anthropology Human Ecology Division UMSA Lund University, Sweden La Paz, Bolivia Title and Subtitle: Attracting and Banning Ankari: Musical and Climate Change in the Kallawaya Region in Northern Bolivia Author: Sebastian Hachmeyer Examination: Master’s thesis (two year) Term: Spring Term 2015 Abstract: In the Kallawaya region in the Northern Bolivian Andes musical practices are closely related to the social, natural and spiritual environment: This is evident during the process of constructing and tuning instruments, but also during activities in the agrarian cycle, collective ritual and healing practices, as means of communication with the ancestors and, based on a Kallawaya perspective, during the critical involvement in influencing local weather events. In order to understand the complexity of climate change in the Kallawaya region beyond Western ontological principles the latter is of great importance. The Northern Bolivian Kallawaya refer to changes in climate as a complex of changes in local human-human and human- environmental relations based on a rupture of a certain morality and reciprocal relationship in an animate world in which music plays an important role. -

Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes

Nymsuque: Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes Beatriz Goubert Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Beatriz Goubert All rights reserved ABSTRACT Nymsuque: Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes Beatriz Goubert Muiscas figure prominently in Colombian national historical accounts as a worthy and valuable indigenous culture, comparable to the Incas and Aztecs, but without their architectural grandeur. The magnificent goldsmith’s art locates them on a transnational level as part of the legend of El Dorado. Today, though the population is small, Muiscas are committed to cultural revitalization. The 19th century project of constructing the Colombian nation split the official Muisca history in two. A radical division was established between the illustrious indigenous past exemplified through Muisca culture as an advanced, but extinct civilization, and the assimilation politics established for the indigenous survivors, who were considered degraded subjects to be incorporated into the national project as regular citizens (mestizos). More than a century later, and supported in the 1991’s multicultural Colombian Constitution, the nation-state recognized the existence of five Muisca cabildos (indigenous governments) in the Bogotá Plateau, two in the capital city and three in nearby towns. As part of their legal battle for achieving recognition and maintaining it, these Muisca communities started a process of cultural revitalization focused on language, musical traditions, and healing practices. Today’s Muiscas incorporate references from the colonial archive, archeological collections, and scholars’ interpretations of these sources into their contemporary cultural practices. -

DICCIONARIO BILINGÜE, Iskay Simipi Yuyayk'ancha

DICCIONARIO BILINGÜE Iskay simipi yuyayk’ancha Quechua – Castellano Castellano – Quechua Teofilo Laime Ajacopa Segunda edición mejorada1 Ñawpa yanapaqkuna: Efraín Cazazola Félix Layme Pairumani Juk ñiqi p’anqata ñawirispa allinchaq: Pedro Plaza Martínez La Paz - Bolivia Enero, 2007 1 Ésta es la version preliminar de la segunda edición. Su mejoramiento todavía está en curso, realizando inclusión de otros detalles lexicográficos y su revisión. 1 DICCIONARIO BILINGÜE CONTENIDO Presentación por Xavier Albo 2 Introducción 5 Diccionarios quechuas 5 Este diccionario 5 Breve historia del alfabeto 6 Posiciones de consonantes en el plano fonológico del quechua 7 Las vocales quechuas y aimaras 7 Para terminar 8 Bibliografía 8 Nota sobre la normalización de las entradas léxicas 9 Abreviaturas y símbolos usados 9 Diccionario quechua - castellano 10 A 10 KH 47 P 75 S 104 CH 18 K' 50 PH 81 T 112 CHH 24 L 55 P' 84 TH 117 CH' 26 LL 57 Q 86 T' 119 I 31 M 62 QH 91 U 123 J 34 N 72 Q' 96 W 127 K 41 Ñ 73 R 99 Y 137 Sufijos quechuas 142 Diccionario castellano - quechua 145 A 145 I 181 O 191 V 208 B 154 J 183 P 193 W 209 C 156 K 184 Q 197 X 210 D 164 L 184 R 198 Y 210 E 169 LL 186 RR 202 Z 211 F 175 M 187 S 202 G 177 N 190 T 205 H 179 Ñ 191 U 207 Sufijos quechuas 213 Bibliografía 215 Datos biográficos del autor 215 LICENCIA Se puede copiar y distribuir este libro bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons Atribución-LicenciarIgual 2.5 con atribución a Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Efraín Cazazola, Félix Layme Pairumani y Pedro Plaza Martínez. -

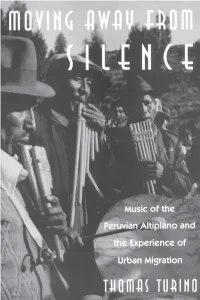

Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experiment of Urban Migration / Thomas Turino

MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl EDITORIAL BOARD Margaret J. Kartomi Hiromi Lorraine Sakata Anthony Seeger Kay Kaufman Shelemay Bonnie c. Wade Thomas Turino MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THOMAS TURlNo is associate professor of music at the University of Ulinois, Urbana. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1993 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1993 Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-81699-0 ISBN (paper): 0-226-81700-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Turino, Thomas. Moving away from silence: music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the experiment of urban migration / Thomas Turino. p. cm. - (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology) Discography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Folk music-Peru-Conirna (District)-History and criticism. 2. Folk music-Peru-Lirna-History and criticism. 3. Rural-urban migration-Peru. I. Title. II. Series. ML3575.P4T87 1993 761.62'688508536 dc20 92-26935 CIP MN @) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. For Elisabeth CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: From Conima to Lima -

Department of Music About the Department

Module options for visiting students Department of Music About the department The internationally-renowned Department of Music is one of the largest and most distinguished in the United Kingdom and in the 2008 government-led Research Assessment Exercise, the department was rated top in the country. The modules listed below are available to all Study Abroad, International Exchange and Erasmus Students, provided that sufficient prior knowledge and experience of the subject can be shown where required. The Music Department reserves the right to review each application to assess the suitability of the applicant and his/her chosen module(s). Entry requirements The modules listed below are open to all Study Abroad, International and Erasmus students, subject to any required previous knowledge or qualifications, as stated in the module outlines below. Each module is either 15 or 30 UK credits and starts in either the Autumn Term (September) or the Spring Term (January). Level One Modules: There are no formal pre-requisites, but a background in music and music theory is seen as very beneficial to students. Students without A Level Music or Grade 8 ABRSM Theory (or equivalent) will be required to take MU1111 Fundamentals of Music Theory in their first term. Level Two Modules: A solid foundation in the rudiments of Western music (an ability to read music fluently, identify key signatures, rhythms, etc.) plus an understanding of Western harmony (an ability to write and/or identify harmonic progressions) is required for Intermediate modules, as well as completion of any first year modules at undergraduate level in music theory. -

Las Implicaciones Socioculturales De La Organización Dual Del Territorio En El Pueblo Quechua De Colcabamba

69 SANQU Y MARAS: LAS IMPLICACIONES SOCIOCULTURALES DE LA ORGANIZACIÓN DUAL DEL TERRITORIO EN EL PUEBLO QUECHUA DE COLCABAMBA NÉSTOR GODOFREDO TAIPE CAMPOS Introducción Al mirar a la iglesia desde la parte baja de la plaza de Colcabamba (en Tayacaja, Huancavelica), la encontramos ubicada exactamente en la mitad superior del parque1. Inclusive hay una cruz en el centro del ángulo superior del frontis, entre las dos torres del templo construido en 1610 (ver ilustración 1). Ilustración 1. Plaza de Colcabamba (Foto: Néstor Taipe, 2017). Este punto medianero marca la división en dos mitades o parcialidades a la villa capital del distrito y, principalmente, a la Comunidad Campesina de Colcabamba2. Una ex autoridad comunal y líder gremial, declaró que: 1 Lo que no ocurre con muchas iglesias, sólo por mencionar algunas, son diferentes las ubicaciones de la Catedral San Antonio de Huancavelica, la Basílica Santa María de Ayacucho, la Iglesia Matriz de Santa Fe de Jauja y la Basílica Catedral de Huancayo. 2 Colcabamba es un distrito, un centro poblado capital del distrito y una comunidad campesina. 70 PERSPECTIVAS LATINOAMERICANAS NÚMERO 14, 2017 N. GODOFREDO: SANQU Y MARAS “La mitad de la iglesia, la mitad del pino, la mitad de la plaza y toda la línea imaginaria RAÍZ FORMA SIGNIFICADO SINÓNIMO FUENTE 3 hacia el este es Sanco [Sanqu] y hacia el oeste es Maras” . Unquy Qolca Pléyades. AMLQ, 2005 quyllurkuna Unquy Laime y otros, ¿Cuáles son los significados Colcabamba, Sanqu y Maras? ¿Cuáles son las implicaciones Qullqa Pléyades. sociales y culturales de esta organización dual del territorio en Colcabamba? Estas son las quyllurkuna 2007 Acosta, interrogantes que pretendo responder. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

La Reconstitución De La Nación Sora: Propuesta Para La Refundación Del País Ayllus De Cochabamba “Bolivia Se Fundó Sobre

La Reconstitución de la Nación Sora: propuesta para la refundación del país Ayllus de Cochabamba “Bolivia se fundó sobre la injusticia. La Constitución Política de 1826 excluyó al noventa por ciento de sus habitantes, y Bolivia siguió siendo dependiente, sometida, su territorio fue descuartizado y sus riquezas sirvieron para el disfrute de una pequeña elite aliada a los intereses extranjeros. Ahora por primera vez, las mayorías nacionales son protagonistas de su historia. Este es un año de cambio, el Pachakuti, el Jach’a uru están llegando con nuestra Revolución Democrática y Cultural. La Asamblea Constituyente debe servir para que los pobres de las ciudades, los indígenas, los obreros, los campesinos, los oprimidos y los excluidos de siempre, las clases medias, los intelectuales, los policías, militares y empresarios patriotas podamos refundar nuestra Bolivia” (Evo Morales Ayma, Presidente Constitucional de la República de Bolivia, mayo 2006) La historia de los ayllus en lo que hoy es el departamento de Cochabamba es la historia de la colonización. La exaltación de una supuesta identidad mestiza, producto de la mezcla entre los contingentes invasores españoles y los pueblos nativos asentados en los valles de la antigua Qhuchapampa, ha servido para encubrir un sistemático proceso de negación de la cultura, lengua, identidad, derechos y territorio de ayllus, markas y suyus. Fue la institucionalidad del ayllu que permitió enfrentar exitosamente a la colonización. El gobierno de sus mallkus, como fue el caso de Don Marcos Mamani, cacique de Kirkiyawi, frenó la expansión del latifundio. Desde el bastión de Kirkiyawi los ayllus procedieron a desplegar una acción de reconstitución que ha conllevado el cumplimiento de la vieja máxima qhip ñawi , que se ha expresado en un esfuerzo de reconstitución de la memoria y la identidad histórica.