Ancient Nubia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

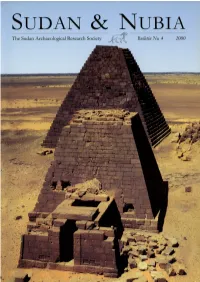

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

King Aspelta's Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan

JOURNAL of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston VOL.6, 1994 Fig. I. Pyramids at Nuri, Sudan, before excava- tion; Aspelta’s is the steeply sloped one, just left of the largest pyramid. SUSANNEGANSICKE King Aspelta’s Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan Introduction A GROUP of exquisite vessels, carved from translucent white stone, is included in the Museum of Fine Arts’s first permanent gallery of ancient Nubian art, which opened in May 1992. All originate from the same archaeological find, the tomb of King Aspelta, who ruled about 600-580 B.C. over the kingdom of Kush (also called Nubia), located along the banks of the Nile in what is today the northern Sudan. The vessels are believed to have contained perfumes or ointments. Five bear the king’s name, and three have his name and additional inscrip- tions. Several are so finely carved as to have almost eggshell-thin sides. One is decorated with a most unusual metal mount, fabricated from gilded silver, which has a curtain of swinging, braided, gold chains hanging from its rim, each suspending a jewel of colored stone. While all of Aspelta’s vessels display ingenious craftsmanship and pose important questions regarding the sources of their materials and places of manufacture, this last one is the most puzzling. The rim with hanging chains, for example, is a type of decoration previ- ously known only outside the Nile Valley on select Greek or Greek- influenced objects. A technical examination, carried out as part of the conservation work necessary to prepare the vessels for display, supplied many new insights into the techniques of their manufacture and clues to their possible origin. -

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964)

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) Lake Nasser, Lower Nubia: photography by the author Degree project in Egyptology/Examensarbete i Egyptologi Carolin Johansson February 2014 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University Examinator: Dr. Sami Uljas Supervisors: Prof. Irmgard Hein & Dr. Daniel Löwenborg Author: Carolin Johansson, 2014 Svensk titel: Digital rekonstruktion av det arkeologiska landskapet i koncessionsområdet tillhörande den Samnordiska Expeditionen till Sudanska Nubien (1960–1964) English title: Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) A Magister thesis in Egyptology, Uppsala University Keywords: Nubia, Geographical Information System (GIS), Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE), digitalisation, digital elevation model. Carolin Johansson, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Box 626 SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. Abstract The Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE) was one of the substantial contributions of crucial salvage archaeology within the International Nubian Campaign which was pursued in conjunction with the building of the High Dam at Aswan in the early 1960’s. A large quantity of archaeological data was collected by the SJE in a continuous area of northernmost Sudan and published during the subsequent decades. The present study aimed at transferring the geographical aspects of that data into a digital format thus enabling spatial enquires on the archaeological information to be performed in a computerised manner within a geographical information system (GIS). The landscape of the concession area, which is now completely submerged by the water masses of Lake Nasser, was digitally reconstructed in order to approximate the physical environment which the human societies of ancient Nubia inhabited. -

The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe

The Archaeological Sites of The Island of Meroe Nomination File: World Heritage Centre January 2010 The Republic of the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums 0 The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe Nomination File: World Heritage Centre January 2010 The Republic of the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums Preparers: - Dr Salah Mohamed Ahmed - Dr Derek Welsby Preparer (Consultant) Pr. Henry Cleere Team of the “Draft” Management Plan Dr Paul Bidwell Dr. Nick Hodgson Mr. Terry Frain Dr. David Sherlock Management Plan Dr. Sami el-Masri Topographical Work Dr. Mario Santana Quintero Miss Sarah Seranno 1 Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………. 5 1- Identification of the Property………………………………………………… 8 1. a State Party……………………………………………………………………… 8 1. b State, Province, or Region……………………………………………………… 8 1. c Name of Property………………………………………………………………. 8 1. d Geographical coordinates………………………………………………………. 8 1. e Maps and plans showing the boundaries of the nominated site(s) and buffer 9 zones…………………………………………………………………………………… 1. f. Area of nominated properties and proposed buffer zones…………………….. 29 2- Description…………………………………………………………………………. 30 2. a. 1 Description of the nominated properties………………………………........... 30 2. a. 1 General introduction…………………………………………………… 30 2. a. 2 Kushite utilization of the Keraba and Western Boutana……………… 32 2. a. 3 Meroe…………………………………………………………………… 33 2. a. 4 Musawwarat es-Sufra…………………………………………………… 43 2. a. 5 Naqa…………………………………………………………………..... 47 2. b History and development………………………………………………………. 51 2. b. 1 A brief history of the Sudan……………………………………………. 51 2. b. 2 The Kushite civilization and the Island of Meroe……………………… 52 3- Justification for inscription………………………………………………………… 54 …3. a. 1 Proposed statement of outstanding universal value …………………… 54 3. a. 2 Criteria under which inscription is proposed (and justification for 54 inscription under these criteria)………………………………………………………… ..3. -

Priestess, Queen, Goddess

Solange Ashby Priestess, queen, goddess 2 Priestess, queen, goddess The divine feminine in the kingdom of Kush Solange Ashby The symbol of the kandaka1 – “Nubian Queen” – has been used powerfully in present-day uprisings in Sudan, which toppled the military rule of Omar al-Bashir in 2019 and became a rallying point as the people of Sudan fought for #Sudaxit – a return to African traditions and rule and an ouster of Arab rule and cultural dominance.2 The figure of the kandake continues to reverberate powerfully in the modern Sudanese consciousness. Yet few people outside Sudan or the field of Egyptology are familiar with the figure of the kandake, a title held by some of the queens of Meroe, the final Kushite kingdom in ancient Sudan. When translated as “Nubian Queen,” this title provides an aspirational and descriptive symbol for African women in the diaspora, connoting a woman who is powerful, regal, African. This chapter will provide the historical background of the ruling queens of Kush, a land that many know only through the Bible. Africans appear in the Hebrew Bible, where they are fre- ”which is translated “Ethiopian , יִׁכוש quently referred to by the ethnically generic Hebrew term or “Cushite.” Kush refers to three successive kingdoms located in Nubia, each of which took the name of its capital city: Kerma (2700–1500 BCE), Napata (800–300 BCE), and Meroe (300 BCE–300 CE). Both terms, “Ethiopian” and “Cushite,” were used interchangeably to designate Nubians, Kushites, Ethiopians, or any person from Africa. In Numbers 12:1, Moses’ wife Zipporah is which is translated as either “Ethiopian” or “Cushite” in modern translations of the , יִׁכוש called Bible.3 The Kushite king Taharqo (690–664 BCE), who ruled Egypt as part of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, is mentioned in the Bible as marching against enemies of Israel, the Assyrians (2Kings 19:9, Isa 37:9). -

Internecine Conflict in the Second Kingdom of Kush

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2013 The Enemy Within: Internecine Conflict in the Second Kingdom of Kush Sophia Farrulla College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Farrulla, Sophia, "The Enemy Within: Internecine Conflict in the Second Kingdom of ushK " (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 771. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/771 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! The!Enemy!Within:! Internecine!Conflict!in!the!Second!Kingdom!of!Kush!! ! ! ! A"thesis"submitted"in"partial"fulfillment"of"the"requirement" for"the"degree"of"Bachelor"of"Arts"in"History"from"" The"College"of"William"and"Mary" " " by" " Sophia"Farrulla" " " " """"""" Accepted"for"____________________________________________" " " " " " """"""""""(Honors,"High"Honors,"Highest"Honors)" " " " !!!!! ! ! ___________________________________________! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Jeremy!Pope,!Director" " " " " " " ___________________________________________" " " " Neil!Norman! ! ! ! ! ! ! ___________________________________________! ! ! ! Ronald!Schechter! " " " " """""""""""""""Williamsburg,"Virginia" " " " " """"""""""April"25,"2013" " i" Contents! -

Sudanese Cultural Heritage Sites Including Sites Recognized As the World Heritage and Those Selected for Being Promoted for Nomination

Sudanese Cultural Heritage Sites Including sites recognized as the World Heritage and those selected for being promoted for nomination Dr. Abdelrahman Ali Mohamed Sudanese Cultural Heritage Sites: Including sites recognized as the World Heritage and those selected for being promoted for nomination / Dr. Abdelrahman Ali Mohamed. – 57p. ©Dr. Abdelrahman Ali Mohamed 2017 ©NCAM – Sudanese National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums 2017 ©UNESCO 2017 With support of the NCAM, UNESCO Khartoum office and Embassy of Switzerland to Sudan and Eritrea Sudanese Cultural Heritage Sites Including sites recognized as the World Heritage and those selected for being promoted for nomination Sudanese Cultural Heritage Sites Forewords This booklet is about the Sudanese Heritage, a cultural part of it. In September-December of 2015, the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM) of the Sudanese Ministry of Tourism, Antiquities and Wildlife, National Commission for Education, Science and Culture, and UNESCO Khartoum office organized a set of expert consultations to review the Sudanese list of monuments, buildings, archaeological places, and other landmarks with outstanding cultural value, which the country recognizes as of being on a level of requirements of the World Heritage Center of UNESCO (WHC). Due to this effort the list of Sudanese Heritage had been extended by four items, and, together with two already nominated as World Heritage Sites (Jebel Barkal and Meroe Island), it currently consists of nine items. This booklet contains short descriptions of theses “official” Sudanese Heritage Sites, complemented by an overview of the Sudanese History. The majority of the text was compiled by Dr. Abdelrahman Ali Mohamed, the General Director of the NCAM. -

The Meroitic Palace B1500 at Napata – Jebel Barkal an Architectural Perspective

Master’s Degree programme in Ancient Civilisations: Literature, History and Archaeology “Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004)” Final Thesis The Meroitic palace B1500 at Napata – Jebel Barkal An architectural perspective Supervisor Ch. Prof. Emanuele M. Ciampini Assistant supervisors Ch. Dr. Marc Maillot Ch. Prof. Luigi Sperti Graduand Silvia Callegher Matriculation Number 832836 Academic Year 2016/2017 Index Index ............................................................................................................................................ 1 General introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 1. Historical introduction ........................................................................................................... 6 2. Other palatial structures at Jebel Barkal ........................................................................... 16 2.1 B1200 ............................................................................................................................... 16 2.2 B100 ................................................................................................................................. 20 2.3 B1700 .............................................................................................................................. 24 2.4 B2400 ............................................................................................................................... 24 2.5 B3200 .............................................................................................................................. -

Kingdom of the Nubian Pharaohs January 8 to 23, 2019

Sudan Kingdom of the Nubian Pharaohs January 8 to 23, 2019 “Stanford Travel/Study changed our ‘travel lives.’ We have great memories of the many places we have been and people with whom we have traveled.” —Julia Vandermade, MBA ’79, The Nile, 2018 HE ENDLESS SANDS OF SUDAN HAVE SECRETS TO TELL IN VOICES worn weary by the T passage of time. Known by the Greeks as Aithiopia (Ethiopia) and by the Egyptians as Kush, this arid desert region was a flourishing center of trade and culture for centuries, made livable by the coursing of the mighty Nile River. From the confluence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile to the mystical peaks of Jebel Barkal, the source of kingship for ancient royalty, we will delve into its rich past. We’ll stand in awe of the pyramids at Napata and Meroë, wander the bones of a once-great medieval city in the north and view the roiling power of the Nile from the top of an Ottoman fort. Join us on this incredible journey, stepping farther back in time with every footprint left in the Sudanese sand! STANFORD TRAVEL/STUDY 650 725 1093 [email protected] Faculty Leader SCOTT PEARSON, who has studied economic change in developing countries for four decades, taught economic development and international trade at the Food Research Institute at Stanford for some 34 years. He’s coauthored a dozen books, won several awards for his research and teaching, and advised governments on food and agricultural policy. He has also traveled and worked abroad in Africa, Asia and Europe and led more than 60 previous trips for Travel/Study. -

Sudan: the Land of the Nubian Pharaohs

Sudan: The Land of the Nubian Pharaohs December 28, 2022 – January 11, 2023 Dear Alumni and Friends, Join your fellow travelers through Sudan, the land of the Nubian Pharaohs. This expedition has been specially designed for CWRU and will be led by none other than our own Dr. Meghan Strong, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Classics and Research Associate at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Dr. Strong has deep ties with this region where she is also the Assistant Director at Nuri, a vast royal Nubian necropolis that is currently under excavation. The trip route will follow the Nile River, the heartbeat of this arid region delving deep into the history of the ancient Nubian kingdoms that were once part of a thriving trade route for centuries influencing the religion, language and culture seen today. During this expedition you will visit archaeological sites arely visited by tourists– pyramids and burial grounds at El-Kurru, Nuri and Meroe, Old Dongola where Coptic churches once stood, and Kerma which was once the capital of the Kingdom of Kush. Celebrate the arrival of new year under the starry desert skies with us. Due to the nature of the destination and limited accommodations, space is limited and I encourage you secure your spot today by contacting our tour operator at (917) 686-2620/ [email protected] or by filling out the enclosed tour reservation form. Sincerely, Brian Amkraut Executive Director, The Laura & Alvin Siegel Lifelong Learning Program Case Western Reserve University Those who have participated in Planned Giving with CWRU are eligible to receive discounts on CWRU Educational Travel programs. -

A Visitor's Guide to the Jebel Barkal Temples

A Visitor's Guide to The Jebel Barkal Temples The NCAM Jebel Barkal Mission Timothy Kendall El-Hassan Ahmed Mohamed Co-Directors 2016 Table of Contents Introduction 3 The Archaeology of the Site 7 Site Map of the Barkal Sanctuary 9 Explanation of the Numbering System used for Excavated Buildings at Jebel Barkal 9 B 100: A Meroitic Palace 10 B 200 and B 300: Temples of the Goddesses Hathor and Mut 12 B 300-sub. The Eighteenth Dynasty Antecedent of B 200 and 300. 23 B 350: The Pinnacle Monument of Taharqa 25 B 500: The Great Temple of Amun of Napata: New Kingdom Phases 35 B 500: The Great Temple of Amun under the Kushites 47 B 500: The Reliefs of Piankhy 53 B 500: The Flag Masts 64 B 500: The Statue Cache 68 B 500 Kiosks: B 501 and B 551 74 B 561-B 560: The Mammisi Temple and Kiosk 82 B 600: The Enthronement Pavilion. 90 B 700: The Temple of Osiris-Dedwen. 94 B 700-sub chapels: Talatat enclosures for the Aten cult. 104 B 800: The Temple of Amun of Karnak at Napata. 110 B 900: The "Lion Temple" 113 B 1100: The "Great House" at Jebel Barkal. 116 B 1200: The Napatan palace and Aspelta throne room. 122 B 1700: A Palace of the High Priest of Amun (?) 127 A Brief History of the NCAM Jebel Barkal Mission, with Staff Acknowledgements 129 (Cover: Gold amulet, 1.5 x 1.2 cm, representing a warrior god, recovered in 2013 during the sifting of a dump from the Reisner excavations in B 1200.