Priestess, Queen, Goddess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

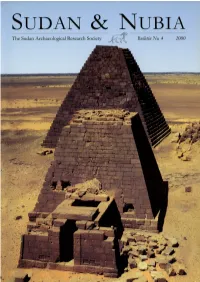

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟S Center on Applied Feminism for Its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟s Center on Applied Feminism for its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference. “Applying Feminism Globally.” Feminism from an African and Matriarchal Culture Perspective How Ancient Africa’s Gender Sensitive Laws and Institutions Can Inform Modern Africa and the World Fatou Kiné CAMARA, PhD Associate Professor of Law, Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, SENEGAL “The German experience should be regarded as a lesson. Initially, after the codification of German law in 1900, academic lectures were still based on a study of private law with reference to Roman law, the Pandectists and Germanic law as the basis for comparison. Since 1918, education in law focused only on national law while the legal-historical and comparative possibilities that were available to adapt the law were largely ignored. Students were unable to critically analyse the law or to resist the German socialist-nationalism system. They had no value system against which their own legal system could be tested.” Du Plessis W. 1 Paper Abstract What explains that in patriarchal societies it is the father who passes on his name to his child while in matriarchal societies the child bears the surname of his mother? The biological reality is the same in both cases: it is the woman who bears the child and gives birth to it. Thus the answer does not lie in biological differences but in cultural ones. So far in feminist literature the analysis relies on a patriarchal background. Not many attempts have been made to consider the way gender has been used in matriarchal societies. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Selima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Reading G Uide

1 Reading Guide Introduction Pharaonic Lives (most items are on map on page 10) Bodies of Water Major Regions Royal Cities Gulf of Suez Faiyum Oasis Akhetaten Sea The Levant Alexandria Nile River Libya Avaris Nile cataracts* Lower Egypt Giza Nile Delta Nubia Herakleopolis Magna Red Sea Palestine Hierakonpolis Punt Kerma *Cataracts shown as lines Sinai Memphis across Nile River Syria Sais Upper Egypt Tanis Thebes 2 Chapter 1 Pharaonic Kingship: Evolution & Ideology Myths Time Periods Significant Artifacts Predynastic Origins of Kingship: Naqada Naqada I The Narmer Palette Period Naqada II The Scorpion Macehead Writing History of Maqada III Pharaohs Old Kingdom Significant Buildings Ideology & Insignia of Middle Kingdom Kingship New Kingdom Tombs at Abydos King’s Divinity Mythology Royal Insignia Royal Names & Titles The Book of the Heavenly Atef Crown The Birth Name Cow Blue Crown (Khepresh) The Golden Horus Name The Contending of Horus Diadem (Seshed) The Horus Name & Seth Double Crown (Pa- The Nesu-Bity Name Death & Resurrection of Sekhemty) The Two Ladies Name Osiris Nemes Headdress Red Crown (Desheret) Hem Deities White Crown (Hedjet) Per-aa (The Great House) The Son of Re Horus Bull’s tail Isis Crook Osiris False beard Maat Flail Nut Rearing cobra (uraeus) Re Seth Vocabulary Divine Forces demi-god heka (divine magic) Good God (netjer netjer) hu (divine utterance) Great God (netjer aa) isfet (chaos) ka-spirit (divine energy) maat (divine order) Other Topics Ramesses II making sia (Divine knowledge) an offering to Ra Kings’ power -

Contagious Faith- Talking About God Without Being Weird.Key

Acts 8:26–30: 26 Now an angel of the Lord said to Philip, “Go south to the road—the desert road—that goes down from Jerusalem to Gaza.” 27 So he started out, and on his way he met an Ethiopian eunuch, an important official in charge of all the treasury of the Kandake (which means “queen of the Ethiopians”). This man had gone to Jerusalem to worship, 28 and on his way home was sitting in his chariot reading the Book of Isaiah the prophet. 29 The Spirit told Philip, “Go to that chariot and stay near it.” 30 Then Philip ran up to the chariot and heard the man reading Isaiah the prophet. “Do you understand what you are reading?” Philip asked. Acts 8:31–35: 31 “How can I,” he said, “unless someone explains it to me?” So he invited Philip to come up and sit with him. 32 This is the passage of Scripture the eunuch was reading: “He was led like a sheep to the slaughter, and as a lamb before its shearer is silent, so he did not open his mouth. 33 In his humiliation he was deprived of justice. Who can speak of his descendants? For his life was taken from the earth.” 34 The eunuch asked Philip, “Tell me, please, who is the prophet talking about, himself or someone else?” 35 Then Philip began with that very passage of Scripture and told him the good news about Jesus. Acts 8:36–40: As they traveled along the road, they came to some water and the eunuch said, “Look, here is water. -

Insights Into a Translucent Name Bead*

INSIGHTS INTO A TRANSLUCENT NAME BEAD* [PLANCHES XIII-XIV] BY PETER PAMMINGER Institut für Ägyptologie der Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität Saarstr. 21 (Campus) D-55099 MAINZ Recently, while visiting a private collection in Belgium, I became aware of a rock- crystal bead of quite distinctive qualities, which might once have belonged to the royal entourage of the 25th dynasty King Piye. The object was acquired not long ago on the art market, unfortunately without any proof of provenance. Its owner was kind enough to grant me permission to publish it. The bead itself (diameter 1.8 to 2.5 cm) has been drilled through (the hole 1.0 to 1.1 cm wide), embodying a sheet of gold in its core. One side of the surface being decorated with a raised cartouche bearing the inscription Mn-Ìpr-R{, the opposite side depicting a vulture1 who is carrying in each claw a symbol of {nÌ. Inbetween these two motives are situated two raised circular dots, each obviously representing a sun-disc (fig. + pl. XIII). * Abbreviations generally in accordance with Helck, W. und W. Westendorf (eds.), Lexikon der Ägyptologie (=LÄ), vol. VII, 1989, p. IX-XXXVIII. In addition: — RMT: Regio Museo di Torino. — Andrews, Jewellery I: C.A.R. Andrews, Jewellery I. From the Earliest Times to the Seventeenth Dynasty. Catalogue of Egyptian Antiquities in the British Museum VI, 1981. — Hall, Royal Scarabs: H.R.(H.) Hall, Catalogue of Egyptian Scarabs, etc., in the British Museum. Vol. I: Royal Scarabs, 1913. — Jaeger, OBO SA 2: B. Jaeger, Essai de classification et datation des scarabées Menkhéperrê (OBO SA 2), 1982. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F.