Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrating Pesach in the Land of the Pharaohs Dr

Celebrating Pesach in the Land of the Pharaohs Dr. Jill Katz Lecturer in Archaeology and Anthropology, Yeshiva University The story of Pesach and the Land of Egypt are inextricably linked. In our recounting, Egypt is always the place we escaped from. We do not really concern ourselves with what happened to Egypt subsequent to our leaving it. Of course, King Shlomo did marry an Egyptian princess and subsequent Israelite and Judahite kings engaged diplomatically with Egyptian leaders. But overall, from the time of the Exodus (yetziat Mitzraim) to near the end of First Temple times, the people of Judah and Israel seemed to have had little interest in returning to the land of their enslavement. However, this changed towards the end of the First Temple period, probably as a result of warming relations brought on by the common threat of the Assyrian Empire. When Egyptian Pharaoh Psamtik (26th Dynasty; 664-610 BCE), needed extra troops to protect Egypt’s southern border from the Nubians, it is quite possible that the king of Judah, Menashe (687-642 BCE), responded favorably. Whatever the origins, we know from written records that by the time the Persians reached Egypt under the leadership of Cyrus’ son and successor Cambyses (525 BCE), a Jewish colony with its own temple was already flourishing in southern Egypt, at a place called Elephantine. Here, Jewish mercenaries were part of a large, Aramaic-speaking community. Within this multi-ethnic context the Jews succeeded in maintaining their distinct religious identity, bolstered by on-going relations with the Jewish communities of Jerusalem and Samaria. -

Les Feuillets D'hermopolis

English translation copyright © Eglise Gnostique Apostolique & +Phillip A. Garver, Ep.Gn.; O.'.C.'.M.'. / O.'.C.'.P.'. - All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents or variations thereon without written consent expressly prohibited. LES FEUILLETS D’HERMOPOLIS - V - April 2002 Monsignor Joseph René VILATTE Paris 1924 – 1929 Mgr. Vilatte is, so to speak, the « father » of the Apostolic Succession of the Gallican Church of Mgr. Giraud and the Gnostic Church, in its apostolic branch, of Mgr. Bricaud and Mgr. Chevillon. His life and his work in Europe and in the United States are well-known from many books and articles, but there is a period that the historians seem to neglect: his return to Paris in 1924, his retirement in Versailles and his death. Let us look at some dates: Joseph - René VILATTE was born on 24 January 1855 in Paris – and died 1 July 1929 in Versailles. (Some biographies indicate 2 July?) Mgr. Herzog, Old Catholic Bishop of Bern conferred upon him Minor Orders, the Sub-Deaconate, the Deaconate and the Priesthood in three days, 5–6–7 June 1885. Mgr. Antoine François Xavier Alvarez (Julius 1st) consecrated him a bishop in the cathedral of Notre Dame de la Bonne Morte in Colombo (Ceylon), 29 May 1892, under the name of Mar Timotheus 1st. Louis Marie - François GIRAUD, was born in Pouzauges (Vendée), 6 May 1876 – and died in 1951. Mgr. Vilatte ordained him a Priest 21 June 1907 in Paris; having transmitted to him the Sub-Deaconate on 14 October 1906 and the Deaconate on 19 March 1907. -

A Greek Inscription

A Greek Inscription: “Jesus is Present” of the Late Roman Period at Beth Loya by Titus Kennedy Introduction At the site of Khirbet Beth Loya, located in the Judean Hills east of Lachish and west of Hebron, a short but important ancient Greek inscription was carved into a rock wall of one of the underground caves. Although the ancient name of the site is unknown at this point, according to discoveries it was a prominent Christian site in the Byzantine period, and possibly earlier. The Byzantine church there is a single apse basilica that was erected ca. 500 AD, remained in use for over 200 years until it was apparently abandoned, and eventually the area was overtaken by a Muslim cemetery.1 Several elaborate mosaics, including Christian inscriptions, designs, and depictions of biblical scenes cover the church floor.2 The site, however, was also occupied earlier, in the Hellenistic and Roman periods.3 The Inscription During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, many subterranean installations were carved out of the soft rock on the site.4 In one of these subterranean caves near the Byzantine era church, an ancient Greek inscription mentions Jesus. The entrance to the cave is now obscured by foliage, but on the wall opposite the entrance, an inscription carved into the limestone can be plainly seen. The letters are much taller and deeper than is usual, which may indicate that it was meant to be plainly seen from anywhere in the small cave. The short inscription, which is all on one line, begins with a simple cross and reads ΙΕCΟΥC ΟΔΕ (or in miniscule ιεσους οδε). -

Ethnic Identity in Graeco-Roman Egypt Instructor

Egypt after the Pharaohs: Ethnic Identity in Graeco-Roman Egypt Instructor: Rachel Mairs [email protected] 401-863-2306 Office hours: Rhode Island Hall 202. Tues 2-3pm, Thurs 11am-12pm, or by appointment. Course Description Egypt under Greek and Roman rule (from c. 332 BC) was a diverse place, its population including Egyptians, Greeks, Jews, Romans, Nubians, Arabs, and even Indians. This course will explore the sometimes controversial subject of ethnic identity and its manifestations in the material and textual record from Graeco-Roman Egypt, through a series of case studies involving individual people and communities. Topics will include multilingualism, ethnic conflict and discrimination, legal systems, and gender, using evidence from contemporary texts on papyrus as well as recent archaeological excavations and field survey projects. Course Objectives By the end of the course, participants should understand and be able to articulate: • how Graeco-Roman Egypt functioned as a diverse multiethnic, multilingual society. • the legal and political frameworks within which this diversity was organised and negotiated. • how research in the social sciences on multilingualism and ethnic identity can be utilised to provide productive and interesting approaches to the textual and archaeological evidence from Graeco-Roman Egypt. Students will also gain a broad overview of Egypt’s history from its conquest by Alexander the Great, through its rule by the Ptolemies, to the defeat of Cleopatra and Mark Antony and its integration into the Roman Empire, to the rise of Christianity. Course Requirements Attendance and participation (10%); assignments (2 short essays of 4-5 pages) and quizzes/map exercises (50%); extended essay on individual topics to be decided in consultation with me (c. -

Stabilisation of Movable Feasts

[Communicated to the Council and the Members of the League.] Official N o.: C. 335. M. 154. 1934. VIII. Geneva. August 3rd, 1934. LEAGUE OF NATIONS ORGANISATION FOR COMMUNICATIONS AND TRANSIT STABILISATION OF MOVABLE FEASTS SUMMARY OF REPLIES FROM RELIGIOUS AUTHORITIES TO THE LETTER FROM THE SECRETARY-GENERAL OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS COMMUNICATING THE ACT REGARDING THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL ASPECTS OF FIXING MOVABLE FEASTS I. — COMMUNICATION OF THE ACT TO THE RELIGIOUS AUTHORITIES. According to the instructions of the Council, the Secretary-General brought the Act regarding the economic and social aspects of fixing movable feasts, adopted by the Fourth General Conference on Communications and Transit, to the notice of the Christian Religious Authorities, asking them to consider as favourably as possible what action they could “take in the matter. As far as the Holy See is concerned, the Act was communicated by letter from the Secretary-General of the League to the Secretary of State of His Holiness on November 16th, As regards Christian Churches other than the Roman Catholic Church, a request was addressed on November 16th, 1932, to the President of the Universal Christian Council for Life and Work, to which all these Churches are affiliated, asking him to bring the above-mentioned Act to their knowledge and to inform the Secretary-General of the League of the views expressed by the Churches in the matter. II. — RESULTS OF THE ENQUIRY. 1. — Attitude of the Holy See. By letter dated December 30th, 1932, Cardinal Pacelli informed the Secretary-General that the Holy bee maintains the point of view already expressed in previous communications — i.e., that the stabilisation of Easter is a pre-eminently religious question which falls within the competence of the Holy See and that, for reasons of higher spiritual concern, the Holy ?>ee cannot contemplate a change in this matter. -

The Last Demotic Inscription

The Last Demotic Inscription Eugene Cruz-Uribe In the course of my work at the temple of Isis on Philae The subject of this short paper is to return to the subject Island, I was able to record a number of new Demotic of what was the last Demotic inscription and offer a new graffiti.1 These graffiti were located in all areas of the tem- alternative in honor of Sven Vleeming so he may enjoy re- ple and I see them as a potentially significant addition to viewing this thesis and hopefully not include it as an entry the corpus of Demotic texts found at the temple. Griffith, in his next Berichtigungsliste volume. who published the first group of these texts,2 noted GPH Thus far it is certain that GPH 365 is the last dated 377, which is located on the roof of the pronaos of the Demotic inscription that has been recorded. In my study temple.3 That text was actually a pair of texts, one being a of the texts at Philae I have pondered the question of the short Demotic graffito and the other being a longer Greek placement of graffiti in the temple and how their loca- text. This text was considered to be the last Demotic graf- tion may give us additional information on why they were fito, as the companion Greek text was dated to 15 Choiak found where they were.8 In my examination of the temples year 169 = 11 December AD 452.4 GPH 365 is now consid- on Philae Island, I also considered my earlier thesis that ered the last Demotic text.5 In Griffith’s publication the the pious Egyptians had a tendency not to write graffiti in date of GPH 365 was read as 6 Choiak 169 = 2 December an ‘active’ portion of a temple.9 Thus I noted the location of AD 452.6 The date, however, has now been correctly many of the Demotic graffiti around Philae temple, but also reread as sw 16, which gives us a date of 12 December around many other temples that have Demotic (or other AD 452.7 ancient Egyptian) graffiti. -

Life in Egypt During the Coptic Period

Paper Abstracts of the First International Coptic Studies Conference Life in Egypt during the Coptic Period From Coptic to Arabic in the Christian Literature of Egypt Adel Y. Sidarus Evora, Portugal After having made the point on multilingualism in Egypt under Graeco- Roman domination (2008/2009), I intend to investigate the situation in the early centuries of Arab Islamic rule (7th–10th centuries). I will look for the shift from Coptic to Arabic in the Christian literature: the last period of literary expression in Coptic, with the decline of Sahidic and the rise of Bohairic, and the beginning of the new Arabic stage. I will try in particular to discover the reasons for the tardiness in the emergence of Copto-Arabic literature in comparison with Graeco-Arabic or Syro-Arabic, not without examining the literary output of the Melkite community of Egypt and of the other minority groups represented by the Jews, but also of Islamic literature in general. Was There a Coptic Community in Greece? Reading in the Text of Evliya Çelebi Ahmed M. M. Amin Fayoum University Evliya Çelebi (1611–1682) is a well-known Turkish traveler who was visiting Greece during 1667–71 and described the Greek cities in his interesting work "Seyahatname". Çelebi mentioned that there was an Egyptian community called "Pharaohs" in the city of Komotini; located in northern Greece, and they spoke their own language; the "Coptic dialect". Çelebi wrote around five pages about this subject and mentioned many incredible stories relating the Prophets Moses, Youssef and Mohamed with Egypt, and other stories about Coptic traditions, ethics and language as well. -

The Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project Field Report 2004-2005 by Peter J

The Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project Field Report 2004-2005 By Peter J. Brand Introduction Collation of Facsimile Drawings of the Battle Reliefs of Ramesses II on the South Wall with Our field work was authorized by Egypt’s Su- Palimpsest of the Battle of Kadesh. preme Council of Antiquities and functioned with the cooperation of the Centre Franco-égyptien pour l’étude The main objective of the season was to com- des Temples de Karnak. We extend our thanks to our plete collation of war scenes on the south exterior wall other Egyptian and French colleagues: Dr. Zahi Hawas, of the Hypostyle Hall in order to produce facsimile President of the SCA, along with the entire Perma- drawings of these reliefs. Initial drawings of these war nent Committee which authorized our work. In Luxor, scenes were first made in 1995. We began collation of we are grateful to Mr. Ibrahim Sulliman, the Director the drawings in 1999 under the Project’s late director, of Karnak and Mr. Fawzy (our inspector); along with professor William J. Murnane. Our collation of the in- Nicolas Grimal and Emanuelle Laroche (scientific and scriptions on this wall was made more difficult by their field directors of the Centre). The expedition staff for poor state of preservation and the fact that part of the this season’s work included two epigraphists: the field wall is a palimpsest in stone with two sets of hieroglyph- director, Dr. Peter Brand of the University of Memphis, ic texts superimposed one atop the other. Tennessee and Dr. Suzanne Onstine from the Univer- sity of Arizona. -

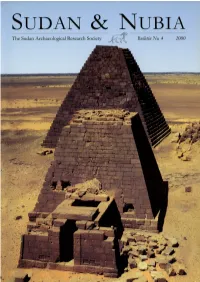

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

The Newsletter of the Friends of the Egypt Centre, Swansea

Price 50p INSCRIPTIONS The Newsletter of the Friends of the Egypt Centre, Swansea Whatever else you do this Issue 28 Christmas… December 2008 In this issue: Re-discovery of the Re-discovery of the South Asasif Necropolis 1 South Asasif Necropolis Fakes Case in the Egypt Centre 2 by Carolyn Graves-Brown ELENA PISCHIKOVA is the Director of the South Introducing Ashleigh 2 Asasif Conservation Project and a Research by Ashleigh Taylor Scholar at the American University in Cairo. On Editorial 3 7 January 2009, she will visit Swansea to speak Introducing Kenneth Griffin 3 on three decorated Late Period tombs that were by Kenneth Griffin recently rediscovered by her team on the West A visit to Highclere Castle 4 Bank at Thebes. by Sheila Nowell Life After Death on the Nile: A Described by travellers of the 19th century as Journey of the Rekhyt to Aswan 5 among the most beautiful of Theban tombs, by L. S. J. Howells these tombs were gradually falling into a state X-raying the Animal Mummies at of destruction. Even in their ruined condition the Egypt Centre: Part One 7 by Kenneth Griffin they have proved capable of offering incredible Objects in the Egypt Centre: surprises. An entire intact wall with an Pottery cones 8 exquisitely carved offering scene in the tomb of by Carolyn Graves-Brown Karakhamun, and the beautifully painted ceiling of the tomb of Irtieru are among them. This promises to be a fascinating talk from a very distinguished speaker. Please do your best to attend and let’s give Dr Pischikova a decent audience! Wednesday 7 January 7 p.m. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic.