The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

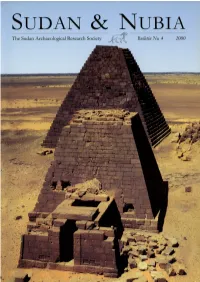

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

The Origins and Afterlives of Kush

THE ORIGINS AND AFTERLIVES OF KUSH ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS PRESENTED FOR THE CONFERENCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA: JULY 25TH - 27TH, 2019 Introduction ....................................................................................................3 Mohamed Ali - Meroitic Political Economy from a Regional Perspective ........................4 Brenda J. Baker - Kush Above the Fourth Cataract: Insights from the Bioarcheology of Nubia expedition ......................................................................................................4 Stanley M. Burnstein - The Phenon Letter and the Function of Greek in Post-Meroitic Nubia ......................................................................................................................5 Michele R. Buzon - Countering the Racist Scholarship of Morphological Research in Nubia ......................................................................................................................6 Susan K. Doll - The Unusual Tomb of Irtieru at Nuri .....................................................6 Denise Doxey and Susanne Gänsicke - The Auloi from Meroe: Reconstructing the Instruments from Queen Amanishakheto’s Pyramid ......................................................7 Faïza Drici - Between Triumph and Defeat: The Legacy of THE Egyptian New Kingdom in Meroitic Martial Imagery ..........................................................................................7 Salim Faraji - William Leo Hansberry, Pioneer of Africana Nubiology: Toward a Transdisciplinary -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 ASWAN LIBYA 1St Cataract

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 ASWAN LIBYA 1st cataract EGYPT Red Sea 2nd cataract K orosk W a d i A o R llaqi W Dal a di G oad a b g a b 3rd cataract a Kawa Kurgus H29 SUDAN H25 4th cataract 5th cataract Magashi a b Dangeil eb r - D owa D am CHAD Wadi H Meroe m a d d Hamadab lk a i q 6th M u El Musawwarat M cataract i es-Sufra d Wad a W ben Naqa A t b a KHARTOUM r a ERITREA B l u e N i le W h i t e N i le Dhang Rial ETHIOPIA CENTRAL SOUTH AFRICAN SUDAN REBUBLIC Jebel Kathangor Jebel Tukyi Maridi Jebel Kachinga JUBA Lulubo Lokabulo Ancient sites Itohom MODERN TOWNS Laboré KENYA ZAIRE 0 200km UGANDA S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 Contents Kirwan Memorial Lecture From Halfa to Kareima: F. W. Green in Sudan 2 W. Vivian Davies Reports Animal Deposits at H29, a Kerma Ancien cemetery 20 The graffiti of Musawwarat es-Sufra: current research 93 in the Northern Dongola Reach on historic inscriptions, images and markings at Pernille Bangsgaard the Great Enclosure Cornelia Kleinitz Kerma in Napata: a new discovery of Kerma graves 26 in the Napatan region (Magashi village) Meroitic Hamadab – a century after its discovery 104 Murtada Bushara Mohamed, Gamal Gaffar Abbass Pawel Wolf, Ulrike Nowotnick and Florian Wöß Elhassan, Mohammed Fath Elrahman Ahmed Post-Meroitic Iron Production: 121 and Alrashed Mohammed Ibrahem Ahmed initial results and interpretations The Korosko Road Project Jane Humphris Recording Egyptian inscriptions in the 30 Kurgus 2012: report on the survey 130 Eastern Desert and elsewhere Isabella Welsby Sjöström W. -

The Meroitic Temple at Sai Island Francigny Vincent

The Meroitic Temple at Sai Island Francigny Vincent To cite this version: Francigny Vincent. The Meroitic Temple at Sai Island. Beiträge zur Sudanforschung, 2016, p. 201-211. halshs-02539292 HAL Id: halshs-02539292 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02539292 Submitted on 15 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. BEITRÄGE ZUR SUDANFORSCHUNG. BEIHEFT 9 THE KUSHITE WORLD PROCEEDINGS OF THE 11TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE FOR MEROITIC STUDIES VIENNA, 1 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2008 THE KUSHITE WORLD PROCEEDINGS OF THE 11TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE FOR MEROITIC STUDIES VIENNA, 1 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2008 Edited by Michael H. Zach Vienna 2015 BEITRÄGE ZUR SUDANFORSCHUNG. BEIHEFT 9 Publisher: Verein der Förderer der Sudanforschung c/o Department of African Studies University of Vienna Spitalgasse 2, Court 5.1 1090 Vienna Austria Printing House: Citypress Neutorgasse 9 1010 Vienna Austria Front Cover: Northern Pylon of Naqa Apedemak Temple (© Department of African Studies, Inv. No. 810) ISSN: 1015-4124 Responsibility of the contents is due to the authors. It is expected that they are in possession of legal permission to publish the enclosed images. CONTENTS Michael H. Zach Address to the 11th International Conference for Meroitic Studies ………………………………… i Hassan Hussein Idris Ahmed Address to the 11th International Conference for Meroitic Studies ………………………………… iii William Y. -

Meroe, Kingdom on the Nile 270 B.C.-A.I)

the gold of meroe The Metropolitan Museum of Art November 23,1993-April 3,1994 EGYPT lower nubia Qasr Ibrim Abu Simbcl Second (Cataract Solch Third Cataract S U D A N 100 mil meroe, kingdom on the nile 270 B.C.-A.I). 350 climate trade ancient world relations Nubia and Egypt, neighbors along the Nile Meroe's location at the convergence of a In the ancient world, the kingdom ofMeroe in northeastern Africa, have long been closely network of caravan roads with Upper Nile existed as an independent state at the borders linked by similar living conditions, but the River trade routes made it East Africa's most of the Hellenistic world and later the Roman Nubian climate is by far the harsher. Restricted important center of trade. Goods traveling empire. There were clashes between the largely to narrow strips of arable land along north into Egypt and the Mediterranean were Meroites and both these world powers, chiefly the riverbanks and confined cast and west age-old African products: gold, ebony, and over control of Lower Nubia. But the Meroites by waterless deserts, Nubia's inhabitants (in ivory. In addition, evidence suggests, Meroites stood their ground, and the largest part of modern southern Egypt and Sudan) live under had a hand in procuring elephants for the war Lower Nubia remained under their control, a scorching sun and with relentless desert machines of the Hellenistic world. For their with Roman influence terminating south winds. Somewhat different living conditions own markets, Meroites manufactured richly of Dakka. prevail in Nubia's deep south where increased decorated cotton textiles, graceful ceramic summer rainfall and seasonal river flow create vessels, bronze and iron objects, and luxury the end a steppe environment (Butana Steppe). -

The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe

The Archaeological Sites of The Island of Meroe Nomination File: World Heritage Centre January 2010 The Republic of the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums 0 The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe Nomination File: World Heritage Centre January 2010 The Republic of the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums Preparers: - Dr Salah Mohamed Ahmed - Dr Derek Welsby Preparer (Consultant) Pr. Henry Cleere Team of the “Draft” Management Plan Dr Paul Bidwell Dr. Nick Hodgson Mr. Terry Frain Dr. David Sherlock Management Plan Dr. Sami el-Masri Topographical Work Dr. Mario Santana Quintero Miss Sarah Seranno 1 Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………. 5 1- Identification of the Property………………………………………………… 8 1. a State Party……………………………………………………………………… 8 1. b State, Province, or Region……………………………………………………… 8 1. c Name of Property………………………………………………………………. 8 1. d Geographical coordinates………………………………………………………. 8 1. e Maps and plans showing the boundaries of the nominated site(s) and buffer 9 zones…………………………………………………………………………………… 1. f. Area of nominated properties and proposed buffer zones…………………….. 29 2- Description…………………………………………………………………………. 30 2. a. 1 Description of the nominated properties………………………………........... 30 2. a. 1 General introduction…………………………………………………… 30 2. a. 2 Kushite utilization of the Keraba and Western Boutana……………… 32 2. a. 3 Meroe…………………………………………………………………… 33 2. a. 4 Musawwarat es-Sufra…………………………………………………… 43 2. a. 5 Naqa…………………………………………………………………..... 47 2. b History and development………………………………………………………. 51 2. b. 1 A brief history of the Sudan……………………………………………. 51 2. b. 2 The Kushite civilization and the Island of Meroe……………………… 52 3- Justification for inscription………………………………………………………… 54 …3. a. 1 Proposed statement of outstanding universal value …………………… 54 3. a. 2 Criteria under which inscription is proposed (and justification for 54 inscription under these criteria)………………………………………………………… ..3. -

Der „Thronschatz" Der Königin Amanishakheto*

Originalveröffentlichung in: C.-B. Arnst, I. Hafemann, A. Lohwasser (Hg.), Begegnungen. Antike Kulturen im Niltal. Festgabe für Erika Endesfelder, Karl-Heinz Priese, Walter Friedrich Reineke und Steffen Wenig. Leipzig 2001, S. 285-302 285 Der „Thronschatz" der Königin Amanishakheto* Angelika Lohwasser Der legendäre Schatzfund, den der italienische Arzt Giuseppe Ferlini im (ahre 1834 in Meroe getätigt hat, ist bis heute einzigartig geblieben. Angefangen von den Fundumständen, die erst 162 lahre später geklärt werden konnten, birgt dieser außergewöhnliche Schmuck der Königin Ama nishakheto noch manches Geheimnis. Es soll hier versucht werden, bei einer dieser Fragen, näm lich der um die ideologische Bedeutung der Darstellungen auf den Siegelplatten der Ringe, der 1 Antwort näher zu kommen . Die Königin Amanishakheto, die die meroitischen Titel kandake und qore trug, wird in die Zeit des 2 ausgehenden I. |h. v. Chr. gesetzt . Von ihr sind eine Reihe von Denkmälern bekannt, die sie im 3 ganzen meroitischen Reich belegen . Über die politischen Ereignisse ihrer Regierung kann man kaum Aussagen machen, jedoch weisen einige Indizien auf Turbulenzen spätestens nach ihrem Tod hin. Zu nennen sind vor allem zwei Umstände: 1. Amanishakheto wird auf den frühen Bele gen stets von dem pcqer und pesto Akinidad begleitet, der bereits erheblichen Einfluß auf die poli tischen Geschicke vielleicht sogar die Thronübernahme der Vorgängerin Amanirenas gehabt hat. Akinidad scheint auch unter Amanishakheto zunächst eine machtvolle Position eingenom men zu haben, wieweit er für ihre Legitimation wichtig war, wissen wir nicht. 2. Darstellungen von zwei Figuren in der Kapelle der Pyramide Beg. N 6, dem Grab der Königin Amanishakheto, sind 4 ausgehackt . -

Priestess, Queen, Goddess

Solange Ashby Priestess, queen, goddess 2 Priestess, queen, goddess The divine feminine in the kingdom of Kush Solange Ashby The symbol of the kandaka1 – “Nubian Queen” – has been used powerfully in present-day uprisings in Sudan, which toppled the military rule of Omar al-Bashir in 2019 and became a rallying point as the people of Sudan fought for #Sudaxit – a return to African traditions and rule and an ouster of Arab rule and cultural dominance.2 The figure of the kandake continues to reverberate powerfully in the modern Sudanese consciousness. Yet few people outside Sudan or the field of Egyptology are familiar with the figure of the kandake, a title held by some of the queens of Meroe, the final Kushite kingdom in ancient Sudan. When translated as “Nubian Queen,” this title provides an aspirational and descriptive symbol for African women in the diaspora, connoting a woman who is powerful, regal, African. This chapter will provide the historical background of the ruling queens of Kush, a land that many know only through the Bible. Africans appear in the Hebrew Bible, where they are fre- ”which is translated “Ethiopian , יִׁכוש quently referred to by the ethnically generic Hebrew term or “Cushite.” Kush refers to three successive kingdoms located in Nubia, each of which took the name of its capital city: Kerma (2700–1500 BCE), Napata (800–300 BCE), and Meroe (300 BCE–300 CE). Both terms, “Ethiopian” and “Cushite,” were used interchangeably to designate Nubians, Kushites, Ethiopians, or any person from Africa. In Numbers 12:1, Moses’ wife Zipporah is which is translated as either “Ethiopian” or “Cushite” in modern translations of the , יִׁכוש called Bible.3 The Kushite king Taharqo (690–664 BCE), who ruled Egypt as part of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, is mentioned in the Bible as marching against enemies of Israel, the Assyrians (2Kings 19:9, Isa 37:9). -

Lecture Transcript: the Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe By

Lecture Transcript: The Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe by Solange Ashby Sunday, August 30, 2020 Louise Bertini: Hello, everyone, and good afternoon or good evening, depending on where you are joining us from, and thank you for joining our August member-only lecture with Dr. Solange Ashby titled "The Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe." I'm Dr. Louise Bertini, and I'm the Executive Director of the American Research Center in Egypt. First, some brief updates from ARCE: Our next podcast episode will be released on September 4th, featuring Dr. Nozomu Kawai of Kanazawa University titled "Tutankhamun's Court." This episode will discuss the political situation during the reign of King Tutankhamun and highlight influential officials in his court. It will also discuss the building program during his reign and the possible motives behind it. As for upcoming events, our next public lecture will be on September 13th and is titled "The Karaites in Egypt: The Preservation of Egyptian Jewish Heritage." This lecture will feature a panel of speakers including Jonathan Cohen, Ambassador of the United States of America to the Arab Republic of Egypt, Magda Haroun, head of the Egyptian Jewish Community, Dr. Yoram Meital, professor of Middle East Studies at Ben-Gurion University, as well as myself, representing ARCE, to discuss the efforts in the preservation of the historic Bassatine Cemetery in Cairo. Our next member-only lecture will be on September 20th with Dr. Jose Galan of the Spanish National Research Council in Madrid titled "A Middle Kingdom Funerary Garden in Thebes." You can find out more about our member-only and public lectures series schedule on our website, arce.org. -

The Sudan National Museum in Khartoum

The Sudan National Museum in Khartoum AN ILLUSTRATED GUIDE FOR VISITORS A short history of the Sudan To get a good overview of the history of the Sudan, it is quite handy to start with a map. Geography explains the history of a country quite well, but it is all the more true in Sudan, a wide desert spread crossed only by the thin strip in the shape of an “S” that is the Middle Nile valley, interrupted by five of the six cataracts. In the entrance of the exhibition hall of the Museum, a big bilingual map (Arabic/English) was put up three years ago. There had to be modifications to be made following the independence of South Sudan. As far as archaeology is concerned, the main topic of this visit is Sudan proper. Ancient remains have been found from the border with Egypt to the Khartoum region and the Blue Nile, but not much to the south. In the South, the soil and the climate do not allow a good preservation of artifacts and skeletons. The cultures that have evolved there were using perishable building materials such as wood that did not survive in the acid soil of the rainforest; whereas in the North, like in Meroe for example, stone and brick architecture buried in the sand can be preserved for millennia and it is the material that Egyptologists are accustomed to study. The border between Egypt and Sudan, today located slightly north of the second cataract, is one of the oldest in the world. It has been there for approximately 5000 years.