The Meroitic Temple at Sai Island Francigny Vincent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

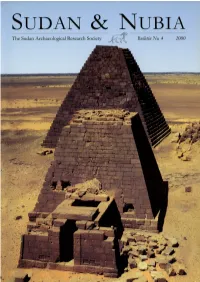

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Seleima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Selima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

Contemporary Islamic Graffiti: the New Illuminated Manuscript

Contemporary Islamic Graffiti: The New Illuminated Manuscript Click the following video link on contemporary Graffiti artist Mohammed Ali. Mohammed was invited to be a part of the Eid Festival at the Riksatern Theatre in Gothenburg Sweden, by the British Council in Seden. He painted a unique cube over a 2 day period outside of the museum, where he engages with the people around him while he paints. http://www.aerosolarabic.com/portfolio/mohammed-ali-in- sweden/ Overview The following lesson is part of a Visual Arts instructional unit exploring Graffiti as a visual art form expressing contemporary ideas of Islamic culture. Historically, Illuminated manuscripts (especially Illuminated Qur’ans) were instrumental in spreading ideas of Islam. The function, form and style development of Illuminated manuscripts correlated with the need to not only record and spread the revelations bestowed upon the prophet Muhammad, but also to signify the importance and reverence of the word of Allah. Contemporary Islamic Graffiti developed in response to a need to illuminate contemporary ideas of Islam in a visual platform that is not only visually captivating, but in the public sphere. Graffiti tends to challenge perceptions and hold a visual mirror up for society to reflect upon cultural practices and structures. Contemporary Islamic Graffiti artists Muhammed Ali and eL Seed are creating a platform for spreading contemporary ideas of Islam and challenging stereotypes and perceptions of Muslims and Islam as a monolithic religion. In this unit, students will first explore the visual art form of historic Illuminated Manuscripts and engage in critical analysis of at least one historic work. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

The Crown of the Divine Child in the Meroitic Kingdom. a Typological Study 1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 37/1 • 2016 • (pp. 17–31) THE CROWN OF THE DIVINE CHILD IN THE MEROITIC KINGDOM. A TYPOLOGICAL STUDY 1 Eric Spindler2 ABSTRACT: The crown of the divine child was one of the headdresses that transferred from Egypt to the Meroitic Kingdom. It was integrated in the Egyptian decoration program in the early Ptolemaic time. The first king of Meroe to use this crown in the decoration of the Lion Temple in Musawwarat es-Sufra was Arnekhamani (235–218 BCE). It also appeared later in the sanctuaries of his successors Arkamani II (218– 200 BCE) and Adikhalamani (ca. 200–190 BCE) in Dakka and Debod. The Egyptians presented it as the headdress of child gods or the king. In the Kingdom of Meroe the crown was more like a tool to depict the fully legitimised king before he faced the main deity of the sanctuary. To show this the Meroitic artists changed its iconography in such a way that the primarily Egyptian focus on the aspects of youth and rebirth withdrew into the background so that the elements of cosmic, royal and divine legitimacy became the centre of attention. Even if the usage and parts of the iconography were different, the overall meaning remained the same. It was a headdress that combined all elements of the cosmos as well as of royal and divine power. KEY WORDS: Crowns – divine child – Meroitic culture – Dakka – Debod – Musawwarat es-Sufra Introduction The beginning of the third century BCE witnessed a marked change in political relations between Egypt and its southern neighbour – Nubia (for a more specified overview of this topic see: Török 1997: 424-432; Welsby 1996: 66-67). -

The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses

The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses provides one of the most comprehensive listings and descriptions of Egyptian deities. Now in its second edition, it contains: ● A new introduction ● Updated entries and four new entries on deities ● Names of the deities as hieroglyphs ● A survey of gods and goddesses as they appear in Classical literature ● An expanded chronology and updated bibliography ● Illustrations of the gods and emblems of each district ● A map of ancient Egypt and a Time Chart. Presenting a vivid picture of the complexity and richness of imagery of Egyptian mythology, students studying Ancient Egypt, travellers, visitors to museums and all those interested in mythology will find this an invaluable resource. George Hart was staff lecturer and educator on the Ancient Egyptian collections in the Education Department of the British Museum. He is now a freelance lecturer and writer. You may also be interested in the following Routledge Student Reference titles: Archaeology: The Key Concepts Edited by Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn Ancient History: Key Themes and Approaches Neville Morley Fifty Key Classical Authors Alison Sharrock and Rhiannon Ash Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, revised by Allen Kendall Who’s Who in the Greek World John Hazel Who’s Who in the Roman World John Hazel The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses George Hart Second edition First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Where Kings Met Gods the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat Es Sufra1

2010 Nachrichten aus Musawwarat Dieter Eigner Where Kings met Gods The Great Enclosure at Musawwarat es Sufra1 The Great Enclosure is the most enigmatic archi- Wolf, P. (2001): “The lion’s den”. Cult temple for tectural monument of the Meroitic culture. Ever Apedemak (temple 100), for his female companion since it became known to the world outside Sudan, (temple 200), mammisi (temple 300). which was through the visit of Linant de Bellefonds Török, L. (2002: 173-186): desert- (hunting- ) in the year 1822, various ideas on function and use palace of the king, and place of his investiture and of the building complex have been put forward by legitimation. Török has changed his opinion about various authors. The most recent overview on these function of architectural elements of the Great ideas was presented by St. Wenig (1999): monastery Enclosure several times (cf. Török 1990: 157, Török or priest’s seminary, teaching institution, hunting 1997: 400, see also Wenig 1999 and 2001), until he palace for the king, “town”, hospital, pleasure palace came to this final conclusion. But Török never had of the Kandake, a khān or desert rest-house, centre doubts about the king being present at the Great for training of elephants, palace with zoological gar- Enclosure at times. den. All these theories are based more or less on mere speculation and show that little or not proper study and analysis of the complex’s architecture was done, Design if it was done at all. But there should be also mentioned G. Erbkam, Most buildings of the Great Enclosure are erected architect of the Lepsius expedition. -

Importing and Exporting Gods? on the Flow of Deities Between Egypt and Its Neighboring Countries

Originalveröffentlichung in: Antje Flüchter, Jivanta Schöttli (Hg.), The Dynamics of Transculturality. Concepts and Institutions in Motion (Transcultural Research – Heidelberg Studies on Asia and Europe in a Global Context), Cham, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London 2015, S. 255-277 Importing and Exporting Gods? On the Flow of Deities Between Egypt and Its Neighboring Countries Joachim Friedrich Quack 1 Introductory Remarks Since the main title of my contribution sounds more economical than ecumenical, I should start with a question: What does it mean to deal in gods? There is one very remarkable passage in an Egyptian text which laments that gods are sold for oxen (Admonitions 8, 12). This phrase seems strange at first sight, so strange that almost all modem editors and commentators have deemed it corrupt and have proposed emendations.1 Actually, it makes perfect sense once you realize that “gods” here means “statues of gods.” These were, in the Egyptian culture, often made of gold, and constituted enough buying power to actually acquire an ox in exchange. The key point for my subsequent analysis is that “gods” have a strongly material ized existence. A god is not simply a transcendent or omnipresent entity but has a focal point in a material object.2 Also, in order to hear the prayers of humans, special proximity is an advantage. Being far from a god in a physical sense was thus seen as a very real menace, and one can see how Egyptians on missions abroad liked to take a transportable figure of their deity with them.3 This also had implications for the opportunities to expand: a figure of the deity at the new cult place was essential and the easiest way to find one would be if you had one that you were free to take with you; this was the case, for instance, with the 1 Most recently Enmarch (2008, 145). -

Assessment of Groundwater Potentiality of Northwest Butana Area, Central Sudan Elsayed Zeinelabdein1, K.A., Elsheikh2, A.E.M., Abdalla, N.H.3

Assessment of groundwater potentiality of northwest Butana Area, Central Sudan Elsayed Zeinelabdein1, K.A., Elsheikh2, A.E.M., Abdalla, N.H.3 1Faculty of Petroleum and minerals – Al Neelain University – Khartoum – Sudan 2 Faculty of Petroleum and minerals – Al Neelain University – Khartoum – Sudan, [email protected], 3Faculty of Petroleum and minerals – Al Neelain University – Khartoum – Sudan, [email protected] Abstract Butana plain is located 150 Km east of Khartoum, it is the most important area for livestock breeding in Sudan. Nevertheless, the area suffers from acute shortage in water supply, especially in dry seasons due to climatic degradation. Considerable efforts were made to solve this problem, but little success was attained. Hills, hillocks, ridges and low lands are the most conspicuous topographic features in the studied area. Geologically, it is covered by Cenozoic sediments and sandstone of Cretaceous age unconformably overlying the Precambrian basement rocks. The objective of the present study is to assess the availability of groundwater resources using remote sensing, geophysical survey and well inventory methods. Different digital image processing techniques were applied to enhance the geological and structural details of the study area, using Landsat (ETM +7) images. Geo-electrical survey was conducted using Vertical Electrical Sounding (VES) technique with Schlumberger array. Resistivity measurements were conducted along profiles perpendicular to the main fracture systems in the area. The present study confirms the existence of two groundwater aquifers. An upper aquifer composed mainly of alluvial sediments and shallow sandstone is found at depths ranging between 20- 30 m, while the lower aquifer is predominantly Cretaceous sandstone found at depths below 50 m.