Archaeological Park Or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Télécharger La Carte Détaillée Du Territoire

e r è z o L (zone inscrite) t l u a r é H Chiffres clés Portrait d'une inscription Key Figures Portrait of an inscription d r a G n o r y e v A Causses & Cévennes 22 000 habitants 3000 km² inscrits Authenticité Aveyron, Gard, Hérault, Lozère, quatre dont 50% de départements se partagent le patrimoine des Authenticity 1 400 éleveurs Causses et des Cévennes et s’associent pour vous Patrimoine Mondial de l'UNESCO This mountainous landscape located in the southern surfaces agricoles à le faire découvrir. part of central France is composed of deep valleys 140 000 brebis C’est un cadre naturel grandiose où depuis des which showcase the evolution of pastoral societies Les Causses et les Cévennes ont été inscrits le 28 juin 2011 sur la liste prestigieuse du Patrimoine Mondial de l’Humanité par l’UNESCO, au titre 80% pastorales millénaires, l’homme a patiemment façonné ces over three thousand years. de la Convention internationale pour la protection du patrimoine naturel et culturel. Cette inscription dans la catégorie des paysages culturels 22 000 inhabitants, 1 400 farmers, 140 000 sheep, 8 500 paysages méditerranéens. 8 500 chèvres The key detail about this landscape is its authenticity évolutifs et vivants porte en elle la reconnaissance internationale d’un territoire façonné par un agropastoralisme méditerranéen millénaire. goats, 8 500 cows. C’est tout un univers minéral où le schiste, le – ancient farms and villages, footpaths and shepherd 50% of farmlands composed of 80% of rangelands among granite et le calcaire se conjuguent pour dessiner trails, and remarkably well-preserved structures and The Causses and the Cevennes were added on the famous UNESCO World Heritage List in 2011 as a living and evolutive cultural landscape. -

The Secession of South Sudan: a Case Study in African Sovereignty and International Recognition

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Political Science Student Work Political Science 2012 The Secession of South Sudan: A Case Study in African Sovereignty and International Recognition Christian Knox College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/polsci_students Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Knox, Christian, "The Secession of South Sudan: A Case Study in African Sovereignty and International Recognition" (2012). Political Science Student Work. 1. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/polsci_students/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Secession of South Sudan: A Case Study in African Sovereignty and International Recognition An Honors Thesis College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for All College Honors and Distinction in the Department of Political Science by Christian Knox May, 2012 Knox 2 ABSTRACT: This thesis focuses on the recent secession of South Sudan. The primary research questions include an examination of whether or not South Sudan’s 2011 secession signaled a break from the O.A.U.’s traditional doctrines of African stability and noninterference. Additionally, this thesis asks: why did the United States and the international community at large confer recognition to South Sudan immediately upon its independence? Theoretical models are used to examine the independent variables of African stability, ethnic secessionism, and geopolitics on the dependent variables of international recognition and the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. -

1 Name 2 History

Sudan This article is about the country. For the geographical two civil wars and the War in the Darfur region. Sudan region, see Sudan (region). suffers from poor human rights most particularly deal- “North Sudan” redirects here. For the Kingdom of North ing with the issues of ethnic cleansing and slavery in the Sudan, see Bir Tawil. nation.[18] For other uses, see Sudan (disambiguation). i as-Sūdān /suːˈdæn/ or 1 Name السودان :Sudan (Arabic /suːˈdɑːn/;[11]), officially the Republic of the Sudan[12] Jumhūrīyat as-Sūdān), is an Arab The country’s place name Sudan is a name given to a جمهورية السودان :Arabic) republic in the Nile Valley of North Africa, bordered by geographic region to the south of the Sahara, stretching Egypt to the north, the Red Sea, Eritrea and Ethiopia to from Western to eastern Central Africa. The name de- the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African or “the ,(بلاد السودان) rives from the Arabic bilād as-sūdān Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west and Libya lands of the Blacks", an expression denoting West Africa to the northwest. It is the third largest country in Africa. and northern-Central Africa.[19] The Nile River divides the country into eastern and west- ern halves.[13] Its predominant religion is Islam.[14] Sudan was home to numerous ancient civilizations, such 2 History as the Kingdom of Kush, Kerma, Nobatia, Alodia, Makuria, Meroë and others, most of which flourished Main article: History of Sudan along the Nile River. During the predynastic period Nu- bia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were identical, simulta- neously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 [15] BC. -

World Heritage Sites in India

World Heritage Sites in India drishtiias.com/printpdf/world-heritage-sites-in-india A World Heritage Site is a place that is listed by UNESCO for its special cultural or physical significance. The list of World Heritage Sites is maintained by the international 'World Heritage Programme', administered by the UNESCO World Heritage Committee. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) seeks to encourage the identification, protection and preservation of cultural and natural heritage around the world considered to be of outstanding value to humanity. This is embodied in an international treaty called the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, adopted by UNESCO in 1972. India has 38 world heritage sites that include 30 Cultural properties, 7 Natural properties and 1 mixed site. Watch Video At: https://youtu.be/lOzxUVCCSug 1/11 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization It was founded in 1945 to develop the “intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind” as a means of building lasting peace. It is located in Paris, France. Cultural Sites in India (30) Agra Fort (1983) 16th-century Mughal monument Fortress of red sandstone It comprises the Jahangir Palace and the Khas Mahal, built by Shah Jahan; audience halls, such as the Diwan-i-Khas Ajanta Caves (1983) Archaeological Site of Nalanda Mahavihara at Nalanda, Bihar (2016) Remains of a monastic and scholastic institution dating from the 3 rd century BCE to the 13th century CE. Includes stupas, shrines, viharas (residential and educational buildings) and important artworks in stucco, stone and metal. Considered to be the most ancient university of the Indian Subcontinent. -

The Influence of South Sudan's Independence on the Nile Basin's Water Politics

A New Stalemate: Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 196 The Influence of South Sudan’s Master thesis in Sustainable Development Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics A New Stalemate: The Influence of South Sudan’s Jon Roozenbeek Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics Jon Roozenbeek Uppsala University, Department of Earth Sciences Master Thesis E, in Sustainable Development, 15 credits Printed at Department of Earth Sciences, Master’s Thesis Geotryckeriet, Uppsala University, Uppsala, 2014. E, 15 credits Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 196 Master thesis in Sustainable Development A New Stalemate: The Influence of South Sudan’s Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics Jon Roozenbeek Supervisor: Ashok Swain Evaluator: Eva Friman Master thesis in Sustainable Development Uppsala University Department of Earth Sciences Content 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Research Aim .................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Purpose ............................................................................................................................ 6 1.3. Methods ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. Case Selection ................................................................................................................. 7 1.5. Limitations ..................................................................................................................... -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

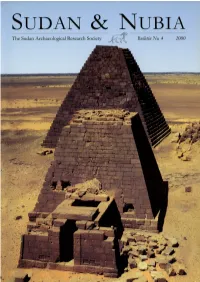

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Worldliness of South Sudan: Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Zachary Mondesire 2018 © Copyright by Zachary Mondesire 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Worldliness of South Sudan: Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba By Zachary Mondesire Master of Art in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Hannah C. Appel, Chair The world’s newest state, South Sudan, became independent in July 2011. In 2013, after the outbreak of the still-ongoing South Sudanese civil war, the UNHCR declared a refugee crisis and continues to document the displacement of millions of South Sudanese citizens. In 2016, Crazy Fox, a popular South Sudanese musician, released a song entitled “Ana Gaid/I am staying.” His song compels us to pay attention to those in South Sudan who have chosen to stay, or to return and still other African regionals from neighboring countries to arrive. The goal of this thesis is to explore the “Crown Lodge,” a hotel in Juba, the capital city of South Sudan, as one such site of arrival, return, and staying put. Paying ethnographic attention to site enables us to think through forms of spatial belonging in and around the hotel that attached racial meaning to national origin and regional identity. ii The thesis of Zachary C. P. Mondesire is approved. Jemima Pierre Aomar Boum Hannah C. Appel, Committee Chair University -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Seleima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

WAR and PROTECTED AREAS AREAS and PROTECTED WAR Vol 14 No 1 Vol 14 Protected Areas Programme Areas Protected

Protected Areas Programme Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Parks Protected Areas Programme © 2004 IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ISSN: 0960-233X Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS CONTENTS Editorial JEFFREY A. MCNEELY 1 Parks in the crossfire: strategies for effective conservation in areas of armed conflict JUDY OGLETHORPE, JAMES SHAMBAUGH AND REBECCA KORMOS 2 Supporting protected areas in a time of political turmoil: the case of World Heritage 2004 Sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo GUY DEBONNET AND KES HILLMAN-SMITH 9 Status of the Comoé National Park, Côte d’Ivoire and the effects of war FRAUKE FISCHER 17 Recovering from conflict: the case of Dinder and other national parks in Sudan WOUTER VAN HOVEN AND MUTASIM BASHIR NIMIR 26 Threats to Nepal’s protected areas PRALAD YONZON 35 Tayrona National Park, Colombia: international support for conflict resolution through tourism JENS BRÜGGEMANN AND EDGAR EMILIO RODRÍGUEZ 40 Establishing a transboundary peace park in the demilitarized zone on the Kuwaiti/Iraqi borders FOZIA ALSDIRAWI AND MUNA FARAJ 48 Résumés/Resumenes 56 Subscription/advertising details inside back cover Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ■ Each issue of Parks addresses a particular theme, in 2004 these are: Vol 14 No 1: War and protected areas Vol 14 No 2: Durban World Parks Congress Vol 14 No 3: Global change and protected areas ■ Parks is the leading global forum for information on issues relating to protected area establishment and management ■ Parks puts protected areas at the forefront of contemporary environmental issues, such as biodiversity conservation and ecologically The international journal for protected area managers sustainable development ISSN: 0960-233X Published three times a year by the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) of IUCN – Subscribing to Parks The World Conservation Union. -

Online Journal in Public Archaeology

ISSN: 2171-6315 Volume 3 - 2013 Editor: Jaime Almansa Sánchez www.arqueologiapublica.es AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology is edited by JAS Arqueología S.L.U. AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology Volume 3 - 2013 p. 46-73 Rescue Archaeology and Spanish Journalism: The Abu Simbel Operation Salomé ZURINAGA FERNÁNDEZ-TORIBIO Archaeologist and Museologist “The formula of journalism is: going, seeing, listening, recording and recounting.” — Enrique Meneses Abstract Building Aswan Dam brought an unprecedented campaign to rescue all the affected archaeological sites in the region. Among them, Abu Simbel, one of the Egyptian icons, whose relocation was minutely followed by the Spanish press. This paper analyzes this coverage and its impact in Spain, one of the participant countries. Keywords Abu Simbel, Journalism, Spain, Rescue Archaeology, Egypt The origin of the relocation and ethical-technical problems Since the formation of UNESCO in 1945, the organisation had never received a request such as the one they did in 1959, when the decision to build the Aswan High Dam (Saad el Aali)—first planned five years prior—was passed, creating the artificial Lake Nasser in Upper Egypt. This would lead to the spectacular International Monuments Rescue Campaign of Nubia that was completed on 10 March 1980. It was through the interest of a Frenchwoman named Christiane Desroches Noblecourt and UNESCO—with the international institution asking her for a complete listing of the temples and monuments that were to be submerged—as well as the establishment of the Documentation Centre in Cairo that the transfer was made possible.