The Amun Temple at Meroe Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

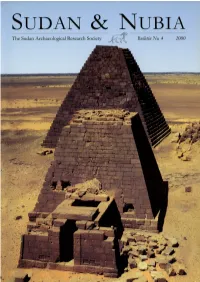

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Seleima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Selima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

Archaeological Park Or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage At

Égypte/Monde arabe 5-6 | 2009 Pratiques du Patrimoine en Égypte et au Soudan Archaeological Park or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage at Naqa in Sudan Parc archéologique ou « Disneyland » ? Conflits d’intérêts sur le patrimoine à Naqa au Soudan Ida Dyrkorn Heierland Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ema/2908 DOI: 10.4000/ema.2908 ISSN: 2090-7273 Publisher CEDEJ - Centre d’études et de documentation économiques juridiques et sociales Printed version Date of publication: 22 December 2009 Number of pages: 355-380 ISBN: 2-905838-43-4 ISSN: 1110-5097 Electronic reference Ida Dyrkorn Heierland, « Archaeological Park or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage at Naqa in Sudan », Égypte/Monde arabe [Online], Troisième série, Pratiques du Patrimoine en Égypte et au Soudan, Online since 31 December 2010, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/ema/2908 ; DOI : 10.4000/ema.2908 © Tous droits réservés IDA DYRKORN HEIERLAND ABSTRACT / RÉSUMÉ ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARK OR “DISNEYLAND”? CONFLICTING INTERESTS ON HERITAGE AT NAQA IN SUDAN The article explores agencies and interests on different levels of scale permeat- ing the constituting, management and use of Sudan’s archaeological heritage today as seen through the case of Naqa. Securing the position of “unique” and “unspoiled sites”, the archaeological community and Sudanese museum staff seem to emphasize the archaeological heritage as an important means for constructing a national identity among Sudanese in general. The government, on the other hand, is mainly concerned with the World Heritage nomination as a possible way to promote Sudan’s global reputation and accelerate the economic exploitation of the most prominent archaeo- logical sites. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Khonsu Sitting in Jebel Barkal

Originalveröffentlichung in: Der Antike Sudan 26, 2015, S. 245-249 201 5 Varia Angelika Lohwasser Khonsu sitting IN Jebel Barkal Dedicated to Tim Kendall for his 70th birthday! Tim Kendall dedicated most of his energy, time and The plaque of green glaze is the item we are analyz thoughts to the Jebel Barkal. Starting with the re- ing. It was numbered as F 989 by von Bissing and is evaluation of the work of George Andrew Reisner, now registered as F 1940/11.49 in the Rijksmuseum he went far beyond the excavation of this forefather van Oudheden in Leiden. of Nubian Archaeology. I have the privilege to reside Although a photograph of it was published by in a house nearby Tim’s digging house in Karima Griffith,4 it escaped the attention of researchers during my own field campaigns; therefore I am one (including Tim), since the black and white photo of the first to learn about his new discoveries and graph is without contrast and difficult to read. considerations. Together we climbed the Jebel Barkal in the moonlight, to see the sunrise and to appreciate the various impressions produced by different lights. Description We had a good time while discussing the situation of Amun being worshipped as a god IN the mountain The dimensions of the rectangular plaque are 2,25 x itself. With this little article I want to contribute to 3,0 x 0,73 cm. It is drilled vertically and decorated Tim’s research on the Jebel Barkal - combining his on both sides. The sides of the plaque are engraved research with my own in Sanam. -

The Origins and Afterlives of Kush

THE ORIGINS AND AFTERLIVES OF KUSH ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS PRESENTED FOR THE CONFERENCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA: JULY 25TH - 27TH, 2019 Introduction ....................................................................................................3 Mohamed Ali - Meroitic Political Economy from a Regional Perspective ........................4 Brenda J. Baker - Kush Above the Fourth Cataract: Insights from the Bioarcheology of Nubia expedition ......................................................................................................4 Stanley M. Burnstein - The Phenon Letter and the Function of Greek in Post-Meroitic Nubia ......................................................................................................................5 Michele R. Buzon - Countering the Racist Scholarship of Morphological Research in Nubia ......................................................................................................................6 Susan K. Doll - The Unusual Tomb of Irtieru at Nuri .....................................................6 Denise Doxey and Susanne Gänsicke - The Auloi from Meroe: Reconstructing the Instruments from Queen Amanishakheto’s Pyramid ......................................................7 Faïza Drici - Between Triumph and Defeat: The Legacy of THE Egyptian New Kingdom in Meroitic Martial Imagery ..........................................................................................7 Salim Faraji - William Leo Hansberry, Pioneer of Africana Nubiology: Toward a Transdisciplinary -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 ASWAN LIBYA 1St Cataract

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 ASWAN LIBYA 1st cataract EGYPT Red Sea 2nd cataract K orosk W a d i A o R llaqi W Dal a di G oad a b g a b 3rd cataract a Kawa Kurgus H29 SUDAN H25 4th cataract 5th cataract Magashi a b Dangeil eb r - D owa D am CHAD Wadi H Meroe m a d d Hamadab lk a i q 6th M u El Musawwarat M cataract i es-Sufra d Wad a W ben Naqa A t b a KHARTOUM r a ERITREA B l u e N i le W h i t e N i le Dhang Rial ETHIOPIA CENTRAL SOUTH AFRICAN SUDAN REBUBLIC Jebel Kathangor Jebel Tukyi Maridi Jebel Kachinga JUBA Lulubo Lokabulo Ancient sites Itohom MODERN TOWNS Laboré KENYA ZAIRE 0 200km UGANDA S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 Contents Kirwan Memorial Lecture From Halfa to Kareima: F. W. Green in Sudan 2 W. Vivian Davies Reports Animal Deposits at H29, a Kerma Ancien cemetery 20 The graffiti of Musawwarat es-Sufra: current research 93 in the Northern Dongola Reach on historic inscriptions, images and markings at Pernille Bangsgaard the Great Enclosure Cornelia Kleinitz Kerma in Napata: a new discovery of Kerma graves 26 in the Napatan region (Magashi village) Meroitic Hamadab – a century after its discovery 104 Murtada Bushara Mohamed, Gamal Gaffar Abbass Pawel Wolf, Ulrike Nowotnick and Florian Wöß Elhassan, Mohammed Fath Elrahman Ahmed Post-Meroitic Iron Production: 121 and Alrashed Mohammed Ibrahem Ahmed initial results and interpretations The Korosko Road Project Jane Humphris Recording Egyptian inscriptions in the 30 Kurgus 2012: report on the survey 130 Eastern Desert and elsewhere Isabella Welsby Sjöström W. -

Settlement in the Heartland of Napatan Kush: Preliminary Results of Magnetic Gradio- Metry at El-Kurru, Jebel Barkal and Sanam

wealth between elites and non-elites; the possible existence Settlement in the Heartland of internal, horizontal social group divisions; and broad af- filiations with varied cultural traditions of architecture. of Napatan Kush: Preliminary Understanding the development of urban settlements is Results of Magnetic Gradio- important to having an adequate account of the operation of ancient societies. Cities themselves have the potential to metry at El-Kurru, Jebel accelerate processes of technological innovation and accumu- lation of wealth, for example (Algaze 2008; Emberling 2015). Barkal and Sanam For all these reasons, it would be highly desirable to under- stand more about the ancient cities of Kush and the nature of Gregory Tucker and Geoff Emberling activities conducted within them. As a first step toward that goal, a preliminary season of geophysical prospection was Ancient Kush was one of the major powers of the ancient undertaken in 2016 at three sites in the heartland of Kush: world with a dynamic, often equal, relationship with Egypt, el-Kurru, Sanam Abu Dom, and Jebel Barkal (Figure 1).1 its northern neighbor. Centered on the Nile in what is now northern Sudan, Kush was first named in Egyptian texts after 2000 BC. Kush was conquered by the armies of the Egyptian New Kingdom after 1500 BC and re-emerged after 800 BC, ruling an expanding area for more than 1000 years until its collapse after AD 300. Its contacts with the broader ancient world – Egypt in particular, but also Assyria, Persia, Greece, and Rome, variously encompassed trade and military conflict. Kush was, however, culturally distinct from its better- known northern neighbors, perhaps in part because of its environmental context – narrow agricultural areas along the Nile surrounded by desert, and distant from the connections facilitated by the Mediterranean – but also because of its distinctive historical and cultural trajectory (Edwards 1998; Emberling 2014) that included a significant component of mobility. -

Nswt-Bity As "King of Egypt and the Sudan" in the 25 .Dynasty and the Kushite Kingdom

ـــــــــــــــــــــ ﻤﺠﻠﺔ ﺍﻻﺘﺤﺎﺩ ﺍﻝﻌﺎﻡ ﻝﻶﺜﺎﺭﻴﻴﻥ ﺍﻝﻌﺭﺏ ( )١٢ Nswt-bity as "king of Egypt and the Sudan " in the 25 th .Dynasty and the Kushite Kingdom D.Hussein M. Rabie ♦♦♦ Inoduction: The Kingdom of Kush was established in the Sudan around the tenth century B.C (1) by local rulers and with local traditions (2). There was a conflict between priests of Amun and the king Tekeloth II in the Twenty Second Dynasty. Tekeloth II had some priests of Amun burned alive and forced some other priests to leave Thebes escaping to Napata (3). The sanity of the area of Napata to Amun and to Theban priests had been established by building an Egyptian temple for the god Amun at Jebel Barkal in the Eighteenth Dynasty. Jebel Barkal was considered as the home of the Ka of Amun, as was mentioned on a stela of Thutmos III (4). Some Scholars think that Amun of Napata was the origin of Amun of Karnak. Ancient Egyptians thought that Jebel -Barkal was the original place of Amun because of his pinnacle shape which ♦Cairo university, Faculty of archaeology, department of Egyptology. (1 ) Reisner suggested 860-820 B.C. as a date of the beginning of this Kingdom, see Trigger B.C. , Nubia under the Pharaohs , London , 1976 , p.140 , while Török considers 1020 B.C. as a date of its beginning –see Török L., " The emergence of the Kingdom of Kush and her myth of the state in the first Millennium B.C. " , in : CRIPEL 17 (1994) , p.108 , and Yellin says that this Kingdom was established shortly after the end of the New Kingdom without giving a determined date –see Yellin J.W., " Egyptian religion and its ongoing impact on the formation of the Napatan state : a contribution to Laszlo Török's main paper The emergence of the Kingdom of Kush and her myth of the state in the First Millennium B.C. -

From the Fjords to the Nile. Essays in Honour of Richard Holton Pierce

From the Fjords to the Nile brings together essays by students and colleagues of Richard Holton Pierce (b. 1935), presented on the occasion of his 80th birthday. It covers topics Steiner, Tsakos and Seland (eds) on the ancient world and the Near East. Pierce is Professor Emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Bergen. Starting out as an expert in Egyptian languages, and of law in Greco-Roman Egypt, his professional interest has spanned from ancient Nubia and Coptic Egypt, to digital humanities and game theory. His contribution as scholar, teacher, supervisor and informal advisor to Norwegian studies in Egyptology, classics, archaeology, history, religion, and linguistics through more than five decades can hardly be overstated. Pål Steiner has an MA in Egyptian archaeology from K.U. Leuven and an MA in religious studies from the University of Bergen, where he has been teaching Ancient Near Eastern religions. He has published a collection of Egyptian myths in Norwegian. He is now an academic librarian at the University of Bergen, while finishing his PhD on Egyptian funerary rituals. Alexandros Tsakos studied history and archaeology at the University of Ioannina, Greece. His Master thesis was written on ancient polytheisms and submitted to the Université Libre, Belgium. He defended his PhD thesis at Humboldt University, Berlin on the topic ‘The Greek Manuscripts on Parchment Discovered at Site SR022.A in the Fourth Cataract Region, North Sudan’. He is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bergen with the project ‘Religious Literacy in Christian Nubia’. He From the Fjords to Nile is a founding member of the Union for Nubian Studies and member of the editorial board of Dotawo.